Chapter 20 Ataxic and Cerebellar Disorders

The term ataxia denotes a syndrome of imbalance and incoordination involving gait, limbs, and speech and usually results from a disorder of the cerebellum and/or its connections. It appears to be derived from the Greek word taxis, meaning “order” (Worth, 2004). Ataxia can also result from a disturbance of proprioceptive input due to pathology along the sensory pathways (sensory ataxia). Evidence from anatomical connectivity studies suggest not only a motor function but also a potential cognitive role for the cerebellum (Strick et al., 2009).The clinical approach to patients with ataxia involves differentiating ataxia from other sources of imbalance and incoordination, distinguishing cerebellar from sensory ataxia, and designing an evaluation based on knowledge of various causes of ataxia and cerebellar disorders (Manto, 2009; Worth, 2004). This chapter describes the clinical features of ataxia and outlines a basic approach to patients with ataxia. A more detailed description of specific disorders can be found elsewhere in this book.

Symptoms and Signs of Ataxic Disorders

A few general statements can be made regarding cerebellar diseases. Lateralized cerebellar lesions cause ipsilateral symptoms and signs, whereas generalized cerebellar lesions give rise to more symmetrical symptomatology. Acute cerebellar lesions often produce severe abnormalities early but may show remarkable recovery with time. Recovery may be less optimal when the deep cerebellar nuclei are involved (Timmann et al., 2008). Chronic progressive diseases of the cerebellum tend to cause gradually declining balance with longer lasting effects. To some extent, signs and symptoms have a relation to the location of the lesions in the cerebellum (Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2010; Timmann et al., 2008). Ataxia of stance and gait are correlated with lesions in the medial and intermediate cerebellum: oculomotor features with medial, dysarthria with intermediate, and limb ataxia with lateral cerebellar lesions (Timmann et al., 2008). Stoodley and Schmahmann (2010) also point out that such lesion/symptom correlation can be extended to the proposed cognitive and limbic aspects of cerebellar function as well with anterior lobe lesions correlating with the traditional motor abnormalities and posterior lobe lesions with cognitive changes.

Symptoms in Patients with Ataxia

Neurological Signs in Patients with Cerebellar Ataxia

Gordon Holmes (1922, 1939) is often credited with the initial description of cerebellar deficits, although earlier works had reported on the effects of cerebellar lesions. Lesions of the cerebellum can cause deficits involving gait and stance, limb incoordination, muscle tone, speech, and the oculomotor system. They may also result in subtle cognitive deficits.

Stance and Gait

Patients with cerebellar disease initially experience an increase in body sway when the feet are placed together; the trunk moves excessively in the sideways direction (lateropulsion). With more severe disease, patients experience the increased sway even with normal stance and learn that balance is better with feet apart. Healthy persons usually have a foot spread of less than 12 cm during normal stance. Patients with cerebellar disease tend to have a much larger foot spread during quiet stance (Manto, 2002). In the clinic, one can detect even subtle problems with balance by asking the patient to do a tandem stance or stand on one foot; normal adults can do these maneuvers for at least 30 seconds. The Romberg test is usually positive in patients with cerebellar ataxia, although this tends to be more prominent in patients with proprioceptive or vestibular lesions. Many patients experience rhythmic oscillations of the trunk and head known as titubation. Severe truncal ataxia can also result in inability to sit upright without back support. Gait can be tested by asking the patient to walk naturally down a straight path. Ataxic gait is characterized by a widened base and an irregular staggering appearance resembling alcoholic intoxication. Overall, the speed of movements is not severely impaired, though patients may deliberately slow down to keep their balance. The steps are irregular, and the patient may lurch in unpredictable ways. Ataxic gait disturbance can be detected even earlier by testing tandem gait; patients with cerebellar lesions lose their ability to do heel-to-toe walking in a straight line.

Abnormalities of Muscle Tone and Strength

Although hypotonia can occur in acute cerebellar disease, it is not a major feature of most cerebellar diseases. The inability of patients to check forearm movement in the rebound test is often said to result from hypotonia but may have other explanations. Similarly, cerebellar lesions do not cause loss of strength in the traditional sense, but many patients experience problems with sustaining a steady force during sustained hand use (isometrataxia) (Manto, 2002).

Oculomotor Disturbances

Routine eye movement examination can detect most of the signs of cerebellar disease (Martin and Corbett, 2000). Fixation abnormalities are examined by asking the patient to maintain sustained gaze at the examiner’s finger held about 2 feet in front. Then the patient is asked to follow the finger as it is moved slowly in all directions of gaze (pursuit). Eccentric gaze is maintained (at ≈ 30 degrees deviation) to check for nystagmus. Saccades are examined by having the patient shift gaze quickly between an eccentrically held finger and the examiner’s nose in the middle. More sophistication can be brought to the clinical examination by looking at the vestibulo-ocular reflex, with the patient in a rotary chair and looking at an object that moves with the chair. A rotating striped drum is used to examine for optokinetic nystagmus (OKN), and Frenzel goggles can be used to remove fixation.

Disorders of Saccades

Saccade velocity is normal in cerebellar disease, but its accuracy is impaired so that both hypometric and hypermetric saccades are seen. Such saccades are followed by a corrective saccade in the appropriate direction (Munoz, 2002).

Speech and Bulbar Function

Speech is evaluated by listening to patients’ spoken words and asking them to speak standard phrases. Speech in cerebellar disease is characterized by slowness, slurring of the words, and a general inability to control the process of articulation, leading to unnecessary hesitations and stops, omissions of pauses when needed, and an accentuation of syllables when not needed. Also, there is a moment-to-moment variability in the volume and pitch of words and inappropriate control of the breathing needed for speech, causing a scanning dysarthria. Both speech execution and the motor programming of speech may be defective in cerebellar disease (Spencer and Slocomb, 2007). Mild dysphagia is not uncommon in cerebellar disease. In children, a form of “cerebellar mutism” has been described after posterior fossa surgery. This is transient and followed by more typical cerebellar dysarthria.

Diagnostic Approach to Ataxia

Neurological examination also determines whether the ataxia is primarily cerebellar, primarily sensory, or a combination of both. This led Greenfield to classify ataxic disorders as spinal, cerebellar, or spinocerebellar in nature. Further diagnostic considerations and avenues for investigation are aimed at making a specific diagnosis (Box 20.1), and management is dependent on the diagnosis. This can be a daunting task, especially when the disease appears to be “degenerative” in nature (i.e., associated with cerebellar atrophy). As an example, the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man website lists more than 500 genetic disorders alone in which ataxia can occur. In the appropriate clinical setting when the initial diagnostic process (e.g., imaging studies) has been unfruitful, it may be important to educate the patient about the possibility of not being able to come to a specific diagnosis before embarking on an expensive process of laboratory studies. In patients with ataxia, many additional pieces of information may be useful in arriving at a diagnosis. These include age at onset (Table 20.1); the tempo of disease (Table 20.2); whether the ataxia is predominantly spinal, spinocerebellar, cerebellar, or associated with spasticity (Box 20.2); the presence or absence of noncerebellar neurological signs (Table 20.3); the occurrence of any distinctive systemic features (Table 20.4); and the nature of the imaging abnormalities (Table 20.5).

Box 20.1 Acquired and Genetic Causes of Ataxia

Acquired Causes of Ataxia

Congenital: “ataxic” cerebral palsy, other early insults

Vascular: ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, AVMs

Infectious/transmittable: acute cerebellitis, postinfectious encephalomyelitis, cerebellar abscess, Whipple disease, HIV, CJD

Toxic: alcohol, anticonvulsants, mercury, 5FU, cytosine arabinoside, lithium

Neoplastic/compressive: gliomas, ependymomas, meningiomas, basal meningeal carcinomatosis, craniovertebral junction abnormalities

Immune: MS, paraneoplastic syndromes, anti-GAD, gluten ataxia

Genetic Causes of Ataxia

Autosomal recessive: FA, AT, AVED, AOA 1, AOA 2, MIRAS, ARSACS, other newly defined autosomal recessive ataxias

Ataxia in other genetic diseases not traditionally classified as an “ataxia”

Autosomal dominant: SCA types 1 through 31, episodic ataxias (types 1, 2, others)

X-linked, including fragile X tremor-ataxia syndrome (FXTAS)

Mitochondrial: NARP, MELAS, MERRF, others including Kearns-Sayre syndrome

| Age at Onset | Acquired | Genetic |

|---|---|---|

| Infancy | Ataxic cerebral palsy, other intrauterine insults | Inherited congenital ataxias (Joubert, Gillespie) |

| Childhood | Acute cerebellitis; cerebellar abscess; posterior fossa tumors such as ependymomas, gliomas; AVM; congenital anomalies such as Arnold-Chiari malformation; toxic such as due to anticonvulsants; immune related to neoplasms (opsoclonus-myoclonus) | FA; other recessive ataxias; ataxia associated with other genetic diseases; EA syndromes; mitochondrial disorders; SCAs such as SCA 2, SCA 7, SCA 13, DRPLA |

| Young adult | Abscesses; HIV; mass lesions such as meningiomas, gliomas, AVM; immune such as MS; Arnold-Chiari malformation; hypothyroidism; toxic such as alcohol and anticonvulsants | FA; SCAs, inherited tumor syndromes like von Hippel-Lindau syndrome |

| Older adult | Same as above plus “idiopathic” ataxia, immune related such as anti-GAD and gluten ataxia | More benign SCAs such as SCA 6 |

AVM, Arteriovenous malformation; DRPLA, dentate-rubral-pallidoluysian atrophy; EA, episodic ataxia; FA, Friedreich ataxia; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MS, multiple sclerosis; SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia (note: SCA indicates a dominantly inherited ataxic disease).

Table 20.2 Causes of Ataxia Based on Onset and Course

| Tempo | Acquired Diseases | Genetic Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Episodic | Many inborn errors of metabolism; EA syndromes | |

| Acute (hours/days) | Strokes, ischemic and hemorrhagic; MS; infections; parainfectious syndromes; toxic disorders | |

| Subacute (weeks/months) | Mass lesions in the posterior fossa; meningeal infiltrates; infections such as HIV, CJD; deficiency syndromes such B1 and B12; hypothyroidism; immune disorders such as paraneoplastic, gluten, and anti-GAD ataxia; alcohol | |

| Chronic | Mass lesions such as meningiomas; craniovertebral junction anomalies; alcoholic; idiopathic cerebellar and olivopontocerebellar atrophy; MSA | Most genetic disorders such as FA, AT, and other AR ataxias; SCAs |

AR, Autosomal recessive; AT, ataxia telangiectasia; CJD, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease; EA, episodic ataxia; FA, Friedreich ataxia; GAD, glutamic acid decarboxylase; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MS, multiple sclerosis; MSA, multiple system atrophy; SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia (dominantly inherited).

Box 20.2 Ataxias That Are Primarily Cerebellar, Cerebellar and Sensory, Primarily Sensory, and Associated with Spasticity

Table 20.3 Noncerebellar Neurological Signs or Symptoms That May Help in the Differential Diagnosis of Ataxia

| Non-neurological Signs or Symptoms | Possible Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Focal and lateralized brainstem deficits such as facial palsy, hemiparesis | Posterior circulation strokes, tumors, MS |

| Visual loss from optic atrophy/retinopathy | MS, FA, SCA 7, mitochondrial disease, Refsum disease, AVED |

| Papilledema, headache | Posterior fossa tumors, ataxia as “false localizing” sign |

| Internuclear ophthalmoplegia | Posterior circulation strokes, MS, some SCAs |

| Gaze palsies | Strokes, MS, NPC, MJD, SCAs 1, 2, 7 |

| Ptosis, ophthalmoplegia | Strokes, MS, mitochondrial disease |

| Slow saccades/ocular apraxia | SCA 2, SCA 7, MJD, AT, AOA |

| Downbeat nystagmus | Arnold-Chiari malformation, basilar invagination, SCA 6, EA 2, lithium toxicity |

| Spasticity, upper motor neuron signs | Strokes, MS, tumors compressing brainstem, SCA 1, SCA 3, SCA 7, SCA 8; rarely FA |

| Basal ganglia deficits | Many SCAs like SCA 2, MJD, SCA 1, SCA 12, SCA 17; DRPLA, FXTAS, MSA, Wilson disease, Fahr disease |

| Tremor | SCA 12, SCA 15/16, FXTAS |

| Autonomic failure | Ataxic form of MSA, FXTAS |

| Deafness | Mitochondrial disease; superficial hemosiderosis |

| Epilepsy | Ataxia associated with anticonvulsants; DRPLA, SCA 7, SCA 10 |

| Myoclonus | Mitochondrial disease, Unverricht-Lundborg disease, SCA 7 of early onset, SCA 14, sialidosis, ceroid lipofuscinosis, idiopathic (Ramsay-Hunt syndrome) |

| Palatal myoclonus | Alexander disease, SCA 20 |

| Polyneuropathy | FA, AOA, AVED, SCA 2, MJD, SCA 1, SCA 4, SCA 25 |

| Cognitive decline | Alcohol, MS, CJD, HIV, DRPLA, SCA 12, SCA 13, end-stage SCAs, superficial siderosis |

| Psychiatric features | SCA 12, SCA 17, SCA 27 |

NOTE: The above list is only a rough guide, and a precise diagnosis cannot be based on such phenotypic features alone. This is because phenotype can be variable, and the features indicated may not occur in all individuals with a particular disease. Also, for many of the disorders, the clinical features have been defined on the basis of limited clinical experience.

AOA, Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia; AT, ataxia telangiectasia; AVED, ataxia with vitamin E deficiency; CJD, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease; DRPLA, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy; EA, episodic ataxia; FA, Friedreich ataxia; FXTAS, fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MJD, Machado-Joseph disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; MSA, multiple system atrophy; NPC, Niemann Pick C; SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia.

Table 20.4 Systemic and Laboratory Features That May Be Useful in the Differential Diagnosis of Ataxia

| Systemic Feature | Possible Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Short stature | Mitochondrial disease, early CNS insults, AT |

| Conjunctival telangiectasia | AT |

| Cataracts | Marinesco-Sjögren syndrome, CTX |

| Cataplexy | NPC |

| KF rings | Wilson disease |

| Cervical lipoma | Mitochondrial disease |

| Abnormal ECG, Echocardiogram | FA, mitochondrial disease |

| Organomegaly | Niemann-Pick disease, LOTS, Gaucher disease, alcohol |

| Hypogonadism | Ataxia with hypogonadism (Holmes ataxia) |

| Myopathy | mtDNA mutations, CoQ10 deficiency |

| Diabetes | AT |

| Spine/foot deformity | FA, AT, AVED |

| Increased skin pigmentation | Adrenoleukodystrophy |

| Hematologic malignancy | AT |

| Sinopulmonary infections | AT |

| Tendon xanthomas | CTX |

| High CK | Mitochondrial disease, AOA |

| High α-fetoprotein | AT, AOA 2 |

AOA, Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia; AT, ataxia telangiectasia; AVED, ataxia with vitamin E deficiency; CK, creatine kinase; CNS, central nervous system; CTX, cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis; ECG, electrocardiogram; FA, Friedreich ataxia; LOT, late-onset Tay Sachs disease; NPC, Niemann Pick C disease.

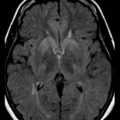

Table 20.5 Brain Imaging Abnormalities That Can Serve to Differentiate the Ataxias

| MRI Abnormality | Possible Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Mass in the cerebellum/posterior fossa | Gliomas, meningiomas, abscess |

| Abnormal craniovertebral junction | Arnold-Chiari malformation, basilar invagination |

| Infarcts, vascular malformations | Ischemic lesions, AVM |

| Signal density change in the cerebellum | MS, acute cerebellitis |

| Signal density change in the MCP | FXTAS |

| Pure cerebellar atrophy | SCAs with pure cerebellar signs (e.g., SCA 5, SCA 6); idiopathic cortical cerebellar atrophy; toxic, deficiency, and autoimmune ataxias |

| Pontocerebellar atrophy | Many SCAs such as SCA 1, 2, and MJD; sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy; ataxic form of MSA |

| Cervical cord atrophy | FA, AVED |

| Cerebral white matter changes | Leukodystrophies presenting with ataxia, MS |

AVED, Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency; AVM, arteriovenous malformation; FA, Friedreich ataxia; FXTAS, Fragile X tremor-ataxia syndrome; MJD, Machado-Joseph disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia.

Holmes G. Clinical symptoms of cerebellar disease and their interpretation. The Croonian lecture III. Lancet. 1922;2:59-65.

Holmes G. The cerebellum of man. Brain. 1939;62:1-30.

Manto M.U. Clinical signs of cerebellar disorders. In: Manto M.U., Pandolfo M. The Cerebellum and Its Disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Manto M., Marmalino D. Cerebellar ataxias. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:419-429.

Martin T.J., Corbett J.J. Neuroopthalmology. St Louis: Mosby; 2000.

Massaquoi S.G., Hallett M. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. Jankovic J., Tolosa E. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, fourth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2002.

Munoz D.P. Saccadic eye movements: Overview of neural circuitry. Prog Brain Res. 2002;140:89-96.

Spencer K.A., Slocomb D.L. The neural basis of ataxic dysarthria. Cerebellum. 2007;6:58-65.

Stoodley C.J., Schmahmann J.D. Evidence for topographic organization in the cerebellum of motor control versus cognitive and affective processing. Cortex. 2010;46:831-844.

Strick P.L., Dum R.P., Fiez J.A. Cerebellum and nonmotor function. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:413-434.

Timmann D., Brandauer B., Hermsdorfer J., et al. Lesion-symptom mapping of the human cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2008;7:602-606.

Worth P.F. Sorting out ataxia in adults. Pract Neurol. 2004;3:130-151.