Chapter 20 Assessment of Restless Legs Syndrome Features With Standardized Methods

Diagnostic assessments and evaluation of therapeutic interventions in patients with restless legs syndrome (RLS) are almost exclusively based on the patient’s subjective reports and, in part, on their clinical interpretation by experts. Similar to the evaluation of psychiatric disorders like depression or anxiety, there is a need for standardized methods that contribute to an increase in the objectivity, reliability, and validity of such judgments by patients and physicians. Surprisingly, the development of standardized methods was delayed in RLS research, with publication of the first method not occurring until 2001,1 although treatment trials had been conducted for two decades, often using polysomnographic measures as outcome variables.

There is a broad potential demand for validated methods both in research and in routine practice. The most important demand is the valid diagnosis of RLS, which needs to identify the presence of the key RLS features, urge to move with or without unpleasant sensations, including their circadian distribution. If distressing symptoms are present, a cascade of impairments of the individual’s life may be activated. The main clinical effect of RLS is disturbed sleep with prolonged sleep latency, sleep fragmentation, and nocturnal sleep deprivation,2 which may result in daytime sleepiness. RLS is usually a chronic disorder with burdening symptoms, and together with continuous sleep problems and daytime somnolence may culminate in an impaired quality of life of the patients, which may also include the development of comorbid psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, or adjustment disorders.3–6

Assessment of Severity of Restless Legs Syndrome

Methodological Problems

Because RLS is a condition characterized largely by subjective symptoms of the patients, it has been important to develop and validate instruments that could be used to measure the severity of the syndrome based on patient rating. It is not yet clear whether severity of RLS is better assessed with items rating the frequency or those rating the intensity of symptoms. In frequency items, patients should report if they have experienced an RLS feature on scales ranging from “never in the last 12 months” to “6 or 7 times a week.” Severity items require a rating of intensity of RLS features on scales ranging from “not present” to “very severe”—either for the current situation or averaged across periods of time, usually 7 days. The number of categories between the extremes varies from one scale to the other. Although frequency questions are preferred in United States, scales developed in Europe make use of intensity ratings. The frequency question appears to be more easily answered objectively, because counting days with symptoms should be more reliable than assessing the severity of a symptom like urge to move. Both types of scaling are highly intercorrelated.7 Frequency-based scales might be poorly sensitive for treatment differences in patients with moderate to severe forms of RLS, but they are very useful for epidemiologic research.7 Intensity ratings are more easily influenced by the specific question wording.

A major use of severity scales is the evaluation of treatments for RLS. Quantitative changes between baseline and end of treatment are analyzed. One important question is how to translate scale changes into clinically relevant changes.8 In addition, different responder criteria (e.g., 50% improvement at end of therapy compared with the baseline value) or remitter criteria (end-of-therapy values below a certain threshold, or even an end-of-treatment score of 0) have been used in clinical trials (e.g., Stiasny-Kolster and colleagues.9). These threshold criteria, however, have not been validated by comparison with investigator-based ratings.10

One way to define a noninferiority margin statistically is the 90% confidence interval of the error of measurement of the severity scale. The noninferiority margin should be within the confidence interval of the error of measurement of the severity scale. For example, when using reliability (Cronbach’s α =.93) and standard deviation (8.8 points) of the IRLS validation study (International Restless Legs Study Group Severity Scale7), the confidence interval calculates to mean ±2.98; thus, a noninferiority margin of 3 IRLS points is achieved. However, statistically developed margins deserve approval from a more clinical perspective.

The definition of a clinically relevant difference between two active treatments or an active treatment and placebo is hampered by largely varying outcomes of clinical trials with drug treatments. Differences in the IRLS between active therapy and placebo were reported between approximately 3 points (ropinirole, e.g., Walters and coworkers11) and more than 8 points (cabergoline, Stiasny-Kolster and coworkers9; rotigotine: Stiasny-Kolster and coworkers12 and Oertel and coworkers13). The margin for clinically relevant differences may be derived from a meta-analysis of all double-blind, randomized drug trials in RLS, which has not yet been conducted.

Instruments

International Restless Legs Syndrome Severity Scale

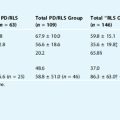

The IRLS (Box 20-1) is a set of 10 questions based largely on features of RLS as proposed by the IRLSSG.14,15 The goal during scale development was to establish a scale that would examine various areas of clinical impact of RLS. The items use 5-point scales that are defined according to the content of the items, with 0 = “symptom not present” to 4 = “very severe intensity.” In a large-scale validation study,7 the IRLS showed excellent psychometric properties (high inter-rater reliability, high retest reliability and internal consistency, high criterion, convergent and discriminant validity). A total score was determined as the sum of the scores of the 10 items, which ranges between 0 = “non RLS” to 40 = “very severe RLS.” The authors of the scale proposed a categorical interpretation of the total score in five classes of severity (0 = no RLS, 1-10 = mild, 11-20 = moderate, 21-30 = severe, 31-40 = very severe RLS). A single-factor solution provided sufficient evidence that a summary score was a useful measure.

BOX 20-1 International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group Rating Scale (IRLS)

Copies of this scale and its translations into several languages can be obtained from Mapi Research Institute, 27, rue de la Villette, 69003 Lyon, France; Fax: +33 (0) 472 13 66 8; e-mail: canfray@mapi.fr; Website: http://www.mapi-research-inst.com. The scale is available free to university or foundation-based researchers; a modest fee is charged for commercial use. Individuals can also contact MAPI if they wish to produce their own translation to discuss methods and to list the new translation with MAPI.

Items

In a separate factor analysis study of the 10 items of the IRLS on 516 self-identified RLS patients, two primary factors were identified—one with six items related to symptom severity and a second factor with three items related to impact of the symptoms on life.16 Recently, a further psychometric study determined that “option characteristic curves” (the probability of scoring different options for a given item as a function of overall IRLS score) and item characteristic curves (the expected score on an item as a function of overall IRLS score) were also generated with the data of a sample of 196 RLS patients. The IRLS items demonstrated excellent item response properties, with option and item characteristic curves closely approximating those of an ideal item. Item 3 (relief of arm or leg discomfort from moving around) was the most problematic item in that a “floor” effect was evident; however, the item response characteristics for this item were still acceptable.17 An additional study indicated that the scale was responsive to changing clinical status in a therapeutic trial.18 The IRLS has also been successfully validated against the number of periodic limb movements (PLM) during sleep on a sleep study or waking during a suggested immobilization test.19

The IRLS has become the “gold standard” in severity assessment in RLS research, especially in clinical drug trials. In all published trials, a difference between active treatment and placebo in changes of the IRLS total score between baseline and end of treatment could be demonstrated that supports the sensitivity of the scale for treatment differences. Nonetheless, it has been argued that the IRLS is prone to large placebo effects.20

Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Severity Scale

The Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Severity Scale (JHRLSS) was first published clinical scale to assess severity of RLS. It consists of one item questioning for the usual (>50% of days) time of the day that symptoms started. A 4-point scale is provided for the patient’s rating (Box 20-2) depending on the time of onset of symptoms: earlier onset is more severe. It has generally been indicated that this measure should apply to subjects with at least near-daily symptoms. The JHRLSS has been validated against objective measures of RLS severity such as sleep efficiency and periodic limb movements.1 It showed high inter-rater agreement and significant correlation with the sleep and movement variables. The JHRLSS measure is a useful, easily used clinical assessment of RLS severity. Like other frequency- or time-based methods, its primary domain is screening and epidemiologic research, but it has also been used to assess severity in pathophysiologic studies.21 As in the case of other frequency or time-based methods, its primary domain is screening and epidemiologic research but not treatment evaluation, with the exception of augmentation. It does have the limitation that it was designed to evaluate RLS patients with daily or near-daily symptoms.

BOX 20-2 Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Syndrome Severity Scale (JHRLSS)

Reprinted with permission from Allen RP, Earley CJ. Validation of the Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Severity Scale. Sleep Med 2001;2:239-242.

The scale asks for typical time of onset of symptoms and scores severity based on this onset time:

RLS-6 Severity Scales

The RLS-6 scales22 have been in use since the early 1990s23; however, over the years, the scales have been extended and modified. The six RLS-6 scales use 11-point scales (0 = “not present” to 10 = “very severe”) to establish a severity profile of different night and daytime periods (Box 20-3). In addition, the patients should report on the quality of sleep and on tiredness/sleepiness during the day. The RLS-6 scales address clinically important dimensions of RLS symptoms and assess treatment outcome as well. Some of these symptoms are specific for RLS (severity of symptoms), but others are nonspecific (quality of sleep, daytime tiredness). The RLS symptoms are usually evaluated for the previous 7 days, but the RLS-6 scales are excellently qualified to be included in patient diaries with evaluation periods of 24 hours.8 The RLS-6 scales were validated in a large trial (n = 361, Kohnen and colleagues8). The evaluation shows close correlation between the RLS-6 scales and the IRLS—around r ≅ 0.40 for the two daytime items but r ≥ 0.60 for all other severity items. The RLS-6 scales are currently the only method in RLS that permits specific assessment of daytime symptoms. This daytime assessment was advantageous in several European clinical trials that showed favorable effects for L-Dopa/benserazide23,24 but even larger effects for the dopamine agonists cabergoline9 and rotigotine.12

BOX 20-3 RLS-6 Scales

Reprinted with permission from Kohnen R, Oertel WH, Stiasny-Kolster K, et al. Severity Rating of Restless Legs Syndrome: Validation of the RLS-6 scales [abstract 680]. Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies (APSS), Philadelphia, 2004. Sleep 2004;27(suppl):A304.

There are 6 Items

Clinical Global Impressions Scales

The Clinical Global Impressions (CGI; National Institute of Mental Health, 1976)42 scales had been initially developed for a risk-benefit estimation within the treatment of mentally ill patients. The CGI with its four global items (or scales) (Box 20-4) is currently the only instrument for evaluation of treatment effects on severity of RLS symptoms that is to be completed by the investigator based on a thorough interview of the patient. Three items are used for efficacy assessment, CGI items 1 “CGI-S” through 3. CGI item 1 assesses “severity of illness.” CGI item 2 “CGI-C” captures any “change in severity” of RLS from baseline. Ratings of “very much” and “much” improved on item 2 have been used as a responder criterion in RLS research. CGI item 3 measures “therapeutic efficacy,” items 2 and 3 are highly correlated. One additional CGI item is related to tolerability; the item asks for the relevance of adverse events (originally, “side effects”) for the patient’s functioning in everyday life. In drug trials, the CGI should be performed by an “independent” physician, one who is not informed about other measures of RLS severity.

BOX 20-4 Clinical Global Impressions

Reprinted with permission from CGI, National Institute of Mental Health. 028 CGI. Clinical Global Impression. In Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, Maryland, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976, pp 217-222.

The CGI, mainly changes in severity of the disorder (item 1) between baseline and end of treatment, is recommended as a co-primary endpoint to a patient-based severity scale for clinical trials by regulatory authorities, although the correlations between the CGI item 1 and the IRLS total score were as high as r = 0.73 in the IRLS validation study7 and little new information may be expected by the independent use of patient- and physician-based measurements. When used in clinical trials, all efficacy items were highly sensitive for treatment differences. It is important to note that in drug trials the CGI should be applied without knowledge of the patients’ ratings on scales, preferably by an expert who is thoroughly trained in the application of the CGI and not involved in other procedures of the study. In published RLS trials, this independent evaluation has often not been maintained.

No models for rater trainings in scales used in RLS research have been evaluated yet.

Clinical Global Impressions for the Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome Patients

The CGI (see previous section) is a global instrument and is not very specific for RLS. Because sensorimotor symptoms and sleep disturbances may independently change in RLS patients over time, the “universal” judgment by the CGI may not be fully appropriate. Hornyak and associates25 proposed an amendment of the CGI item 2 (change of condition) to adjust to possible heterogeneous effects of treatments on RLS symptoms: four items are now used to assess severity of RLS features: two items specifically ask for severity (a) during the night and (b) during the day. Two other scales address potential consequences of RLS symptoms: severity of (c) sleep disturbances and (d) daytime sleepiness/tiredness. The seven categories of the original CGI item 2 (“very much improved” to “very much worse”) are used for evaluation. Primarily the frequency distributions of the categories, but also quantitative statistics, may be applied for this purpose. The validation of these scales is ongoing.

Assessment of Augmentation of Restless Legs Syndrome

Methodological Problems

Augmentation is the main complication during long-term dopaminergic treatment of RLS and reflects an overall increase in RLS severity. A guideline on the definition and clinical criteria of augmentation was developed during a 2006 workshop of the International RLS Study Group.26

If augmentation was reported in published clinical studies, its assessment was based on adhoc constructed criteria27,43 or on the global evaluations of treatment complications (“adverse events”) by study investigators9,28 (and several other publications on clinical trials).

The European RLS Study Group has developed the Augmentation Severity Rating Scale (ASRS) for the quantitative assessment of severity of augmentation in clinical studies, using three items that assess the degree of change in three specific dimensions of augmentation: earlier onset of symptoms during the day, shorter latency to occurrence of symptoms when the patient is at rest, and spreading of symptoms from the legs to other parts of the body.26 The ASRS uses 9-point scales (0 = “no signs of augmentation,” 8 = “signs of severe augmentation”) based on the changes between two assessments (before start of treatment, during treatment). The scores for the three items are summed as the ASRS total score (range, 0 to 24). Reliability and validity of the total ARSR score were demonstrated in a validation study.29 The ASRS is currently the only scale that allows determination of the varying degree of augmentation. A cutoff of at least 5 points in the ASRS total score was recommended as a screener for augmentation.29

Assessment of Sleep Disturbances in Restless Legs Syndrome Patients

Methodological Problems

Nocturnal sleep disturbance is one of the major morbidities associated with RLS. In particular, patients with severe disease have difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep. Sleep duration of moderately to severely affected patients may be shorter than in patients who have other sleep disorders, averaging less than 5 hours per night.27 Several instruments to assess sleep variables have been developed in the past, mainly in psychiatry. Almost all of these methods involve several subscales that are based on theoretical constructs of sleep30 as perceived by the respective authors of those scales. Usually, they include sleep behavior (subjectively assessed sleep onset latency, sleep duration, interruptions of sleep), quality of sleep, and other subjective variables like “adequacy of sleep” or consequences of disturbed sleep such as daytime somnolence.

Selection of the dimensions relevant for RLS and subsequently selection of suitable instruments are the key issues for research. In several clinical drug trials, sleep behavior as assessed on a daily basis with sleep diaries and quality-of-sleep scales like the RLS-6 scale “satisfaction with sleep” were the dominant dimensions, especially in Europe. The Medical Outcome Studies (MOS) Sleep Scale31 (Box 20-5) was used in ropinirole trials (e.g., Walters and colleagues,11 Trenkwalder and colleagues,32 and Allen and colleagues.33), however, not all dimensions of this scale were considered important. Mainly, the subscale “sleep adequacy” was sensitive for differences between treatments (ropinirole) and placebo. In nondrug research, other scales are also administered, such as the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse and coworkers34; see Hornyak and coworkers4).

BOX 20-5 Medical Outcome Studies (MOS) Sleep Scale

Reprinted with permission from Hays RD, Martin SA, Sesti AM, Spritzer KL. Psychometric properties of the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep measure. Sleep Med 2005;6:41-44.

Item Stems

Questions 3 to 12 are all based on a 6-point scale from 1 = “All of the time” to 6 = “None of the time.”

Scores from above are converted to scaled scores that range from 0 to 100 for each item. Depending on the scales below, the scoring may be direct (1 = low to 6 = high) or reversed.

The scale can be downloaded from: http://www.rand.org/health/surveys/sleepscale/.

A scoring guide is also available through a link at that site.

Another sleep-related feature that requires inclusion into RLS research is the occurrence of sudden onset of sleep (SOS). SOS was reported in parkinsonian patients under dopaminergic treatment (e.g., Hobson and associates35). Clinically, two types of SOS can be distinguished: “sleep attacks,” which occur without any prior subjective sleepiness, and “unintended sleep episodes,” which occur together with prior sleepiness. It has been questioned whether “sleep attacks” really exist.36 A single case study described an RLS patient who experienced sleep attacks when the dose of the dopamine agonist pergolide was reduced from 2 mg to 1 mg per day. It disappeared when the patient was switched to pramipexole.37 Fear of putting patients at risk for SOS with possible traffic accidents as consequences has led to efforts to measure the degree of this effect during dopamine agonist treatment. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS),38 the RLS-6 scale “daytime sleepiness,” the CGI-RLS scale “daytime sleepiness,” or the subscale “daytime somnolence” of the MOS Sleep Scale are used for this purpose. It is a usual finding in clinical trials that initial daytime sleepiness approves in RLS patients under dopaminergic treatment.39 However, most studies only consider group statistics (mean or median change from baseline) and do not inspect single cases, which would be more appropriate to identify patients with severe and increasing daytime sleepiness.

Instruments

Medical Outcome Study Sleep Scale

The aim in developing the MOS Sleep Scale30,31 was to include the most applicable theoretical constructs of sleep (see later); the instrument aims to characterize subjective sleep in different subgroups of patients with chronic disorders. Each of a total of 12 items measures a unique aspect or characteristic of sleep. Ten of 12 items (items 3 through 12) are rated with a numerical 6-point scale ranging from 1 = “all of the time” to 6 = “none of the time.” The first item, asking for the time it took to fall asleep, is rated with a numerical 5-point scale ranging from 1 (0 to 15 minutes) to 5 (>60 minutes); item 2 asks for the average sleep duration in hours. Patients should answer each subscale in reference to the 4 weeks before their visit.

For the analysis of the MOS Sleep Scale, the following subscales have been developed: sleep disturbance, sleep adequacy (get amount of sleep needed), daytime somnolence, quantity of sleep, snoring, and awaken with shortness of breath or with headache. In addition, a sleep problems index can be derived from the 12 items. Only the first four subscales were used in the ropinirole trials and found to be sensitive to show differences between active treatment and placebo (in the study of Allen and coworkers,33 only the sleep adequacy scale was discriminating). In a psychometric trial,31 reliability coefficients were moderate as expected from very few items per scale, but acceptable (Cronbach’s α > 0.70, with the exception of daytime somnolence, where it was 0.63). No formal validity evaluation was performed; the scale claims content validity according to the construction principle.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

The ESS was designed to measure the patient’s general level of daytime sleepiness, called the average sleep propensity.38 The total score of eight items representing different situations commonly encountered in daily life is a measure of the probability of falling asleep (to doze off or fall asleep) in a variety of situations (Box 20-6). The ESS showed high divergent validity because the total score distinguished normal subjects from patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, narcolepsy, or idiopathic hypersomnia. Also, convergent validity was ensured by significant correlations of the ESS total score with sleep latency measured during the multiple sleep latency test44 and during overnight polysomnography. These findings were supported by the outcomes of the Italian ESS validation study.40

BOX 20-6 Epworth Sleepiness Scale

In a review, Fulda and Wetter41 demonstrated that as many as 20% to 25% of untreated RLS patients are at an increased risk for daytime sleepiness. To identify patients at risk for SOS, if there will be any, it is recommended to analyze ESS scores greater than 10 (increased daytime sleepiness) or greater than 15 (excessive daytime sleepiness) during study treatment but also to consider single items and evaluate patients more closely who report a high chance of dozing “in a car while stopped for a few minutes in the traffic.”

Summary

1. Allen RP, Earley CJ. Validation of the Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Severity Scale. Sleep Med. 2001;2:239-242.

2. Itin I, Comella CL. Restless legs syndrome. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2005;32:435-448.

3. Kushida CA, Clerk AA, Kirsch CM, et al. Prolonged confusion with nocturnal wandering arising from NREM and REM sleep: A case report. Sleep. 1995;18:757-764.

4. Hornyak M, Kopasz M, Berger M, et al. Impact of sleep-related complaints on depressive symptoms in patients with restless legs syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1139-1145.

5. Winkelmann J, Prager M, Lieb R, et al. “Anxietas tibiarum.” Depression and anxiety disorders in patients with restless legs syndrome. J Neurol. 2005;252:67-71.

6. Picchietti D, Winkelman JW. Restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements in sleep, and depression. Sleep. 2005;28:891-898.

7. International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2003;4:121-132.

8. Kohnen R, Benes H, Leroux M, et al. Defining clinical relevance of treatment outcome in studies with restless legs syndrome patients: Example from the cabergoline dose-finding trial [abstract]. Eighth International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders (Movement Disorder Society), Rome, 2004. Mov Disord. 2004;19(suppl 9):S427.

9. Stiasny-Kolster K, Benes H, et al. Effective cabergoline treatment in idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2004;63:2272-2279.

10. Trenkwalder C, Kohnen R, Allen RP, et al. Clinical investigations of medicinal products in the treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS). Recommendations of the European RLS Study Group (EURLSSG). Mov Disord. 2007;22(suppl 18):S495-S504.

11. Walters AS, Ondo WG, Dreykluft T, et alTREAT RLS 2 (Therapy with Ropinirole: Efficacy And Tolerability in RLS 2) Study Group. Ropinirole is effective in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. TREAT RLS 2: A 12-week, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1414-1423.

12. Stiasny-Kolster K, Kohnen R, Schollmayer E, et alRotigotine Sp 666 Study Group. Patch application of the dopamine agonist rotigotine to patients with moderate to advanced stages of restless legs syndrome: A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1432-1438.

13. Oertel WH, Benes H, Garcia-Borreguero D, et al. Efficacy of rotigotine transdermal system in severe restless legs syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, six-week dose-finding trial in Europe. Sleep Med. 2008;9:228-239.

14. Walters AS. Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Mov Disord. 1995;10:634-642.

15. Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et alRestless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology Workshop at the National Institutes of Health; International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology Workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

16. Allen RP, Kushida CA, Atkinson MJ, RLS Quality of Life Consortium. Factor analysis of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group’s scale for restless legs severity. Sleep Med. 2003;4:133-135.

17. Wunderlich GR, Evans KR, Sills T, et alInternational Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. An item response analysis of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2005;6:131-139.

18. Abetz L, Arbuckle R, Allen RP, et al. The reliability, validity and responsiveness of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale and subscales in a clinical-trial setting. Sleep Med. 2006;7:340-349.

19. Garcia-Borreguero D, Larrosa O, de la, Llave Y, et al. Correlation between rating scales and sleep laboratory measurements in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2004;5:561-565.

20. Fulda S, Wetter TC. Where dopamine meets opioids: A meta-analysis of the placebo effect in RLS treatment studies. Brain. 2007. Epub Oct 11

21. Earley CJ, Barker PB, Horska A, et al. MRI-determined regional brain iron concentrations in early- and late-onset restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2006;7:458-461.

22. Kohnen R, Oertel WH, Stiasny-Kolster K, et al. Severity Rating of Restless Legs Syndrome: Validation of the RLS-6 scales [abstract]. Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies (APSS), Philadelphia, 2004. Sleep. 2004;27(suppl):A304.

23. Trenkwalder C, Stiasny K, Pollmächer T, et al. Effective L-Dopa therapy of uremic and idiopathic restless legs syndrome: A double-blind crossover trial. Sleep. 1995;18:681-688.

24. Beneš H, Kurella B, Kummer J, et al. Rapid onset of action of levodopa in restless legs syndrome: A double-blind, randomized, multicenter, crossover trial. Sleep. 1999;22:1073-1081.

25. Hornyak M, Benes H, Happe S, et al. Investigator ratings of global change in symptoms of RLS patients—A disease-specific amendment to the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) [abstract]. Seventeenth Congress of the European Sleep Research Society, Prague, 2004. J Sleep Res. 13(suppl 1), 2004.

26. García-Borreguero D, Allen RP, Kohnen R, et alon behalf of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG). Diagnostic standards for dopaminergic augmentation of restless legs syndrome: Report from a World Association of Sleep Medicine–International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group Consensus Conference at the Max Planck Institute. Sleep Med. 2007;8:520-530.

27. Allen RP, Earley CJ. Restless legs syndrome: A review of clinical and pathophysiologic features. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18:128-147.

28. Benes H, Heinrich CR, Ueberall MA, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of cabergoline for the treatment of idiopathic restless legs syndrome: Results from an open-label 6-month clinical trial. Sleep. 2004;27:674-682.

29. García-Borreguero D, Kohnen R, Högl B, et al. Validation of the Augmentation Severity Rating Scale (ASRS): A multicentric, prospective study with levodopa on restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2007;8:455-463.

30. Hays RD, Stewart AL. Sleep measures. In: Stewart AL, Ware JE, editors. Measuring Functioning and Well-being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992:235-259.

31. Hays RD, Martin SA, Sesti AM, et al. Psychometric properties of the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep measure. Sleep Med. 2005;6:41-44.

32. Trenkwalder C, Garcia-Borreguero D, Montagna P, et alTherapy With Ropinirole; Efficacy and Tolerability in RLS 1 Study Group. Ropinirole in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: Results from the TREAT RLS 1 study, a 12 week, randomised, placebo controlled study in 10 European countries. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:92-97.

33. Allen R, Becker PM, Bogan R, et al. Ropinirole decreases periodic leg movements and improves sleep parameters in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2004;27:907-914.

34. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF3rd, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193-213.

35. Hobson DE, Lang AE, Martin WR, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden-onset sleep in Parkinson disease: A survey by the Canadian Movement Disorders Group. JAMA. 2002;287:455-463.

36. Roth T, Rye DB, Borchert LD, et al. Assessment of sleepiness and unintended sleep in Parkinson’s disease patients taking dopamine agonists. Sleep Med. 2003;4:275-280.

37. Bassetti C, Clavadetscher S, Gugger M, et al. Pergolide-associated ‘sleep attacks’ in a patient with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2002;3:275-277.

38. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540-545.

39. Moller JC, Korner Y, Cassel W, et al. Sudden onset of sleep and dopaminergic therapy in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2006;7:333-339.

40. Vignatelli L, Plazzi G, Barbato A, et alGINSEN (Gruppo Italiano Narcolessia Studio Epidemiologico Nazionale. Italian version of the Epworth sleepiness scale: External validity. Neurol Sci. 2003;23:295-300.

41. Fulda S, Wetter TC. Is daytime sleepiness a neglected problem in patients with restless legs syndrome? Mov Disord. 2007;22(suppl 18):S409-S413.

42. National Institute of Mental Health. 028 CGI. Clinical Global Impression. In: Guy W, editor. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville: Maryland, National Institute of Mental Health; 1976:217-222.

43. Winkelman JW, Johnston L. Augmentation and tolerance with long-term pramipexole treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS). Sleep Med. 2004;5:9-14.

44. Carskadon MA, Dement WC, Mitler MM, et al. Guidelines for the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT): a standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep. 1986;9:519-524.