Assessment of Posture

Postural Development

Through evolution, human beings have assumed an upright erect or bipedal posture. The advantage of an erect posture is that it enables the hands to be free and the eyes to be farther from the ground so that the individual can see farther ahead. The disadvantages include an increased strain on the spine and lower limbs and comparative difficulties in respiration and transport of the blood to the brain.

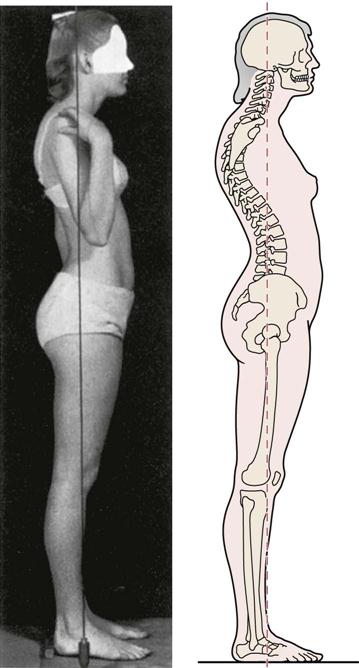

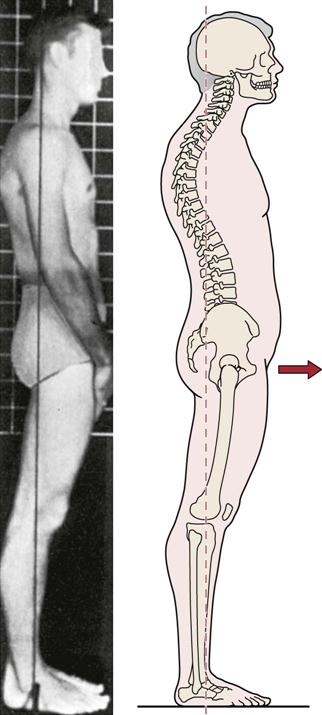

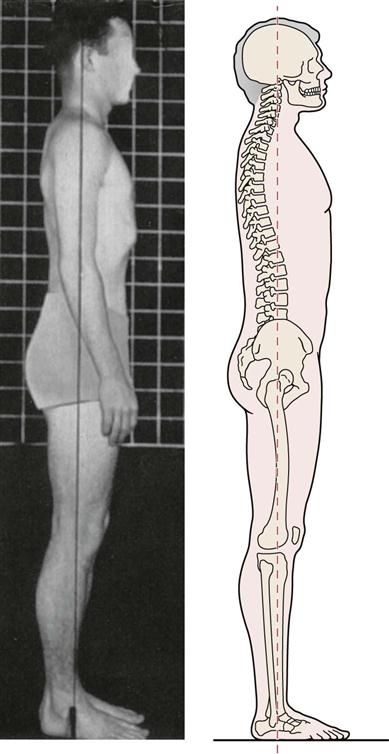

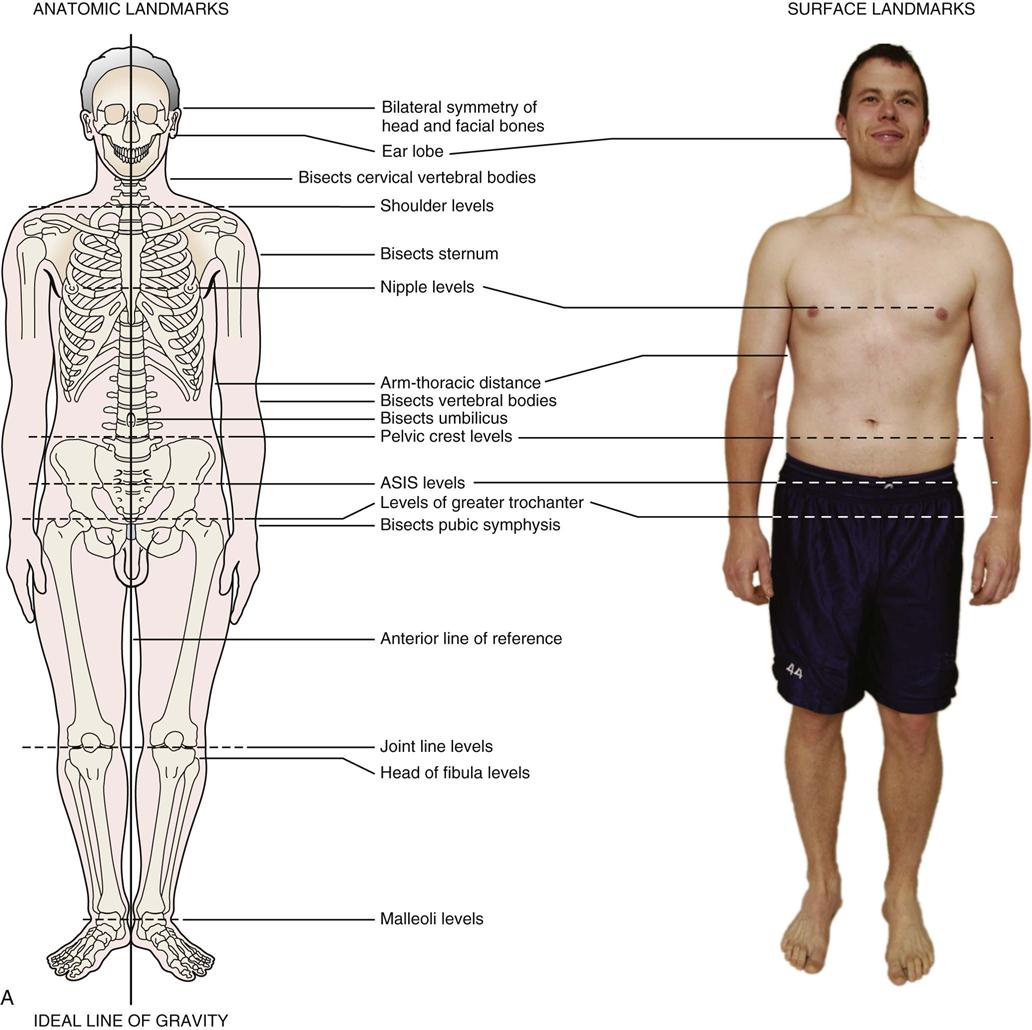

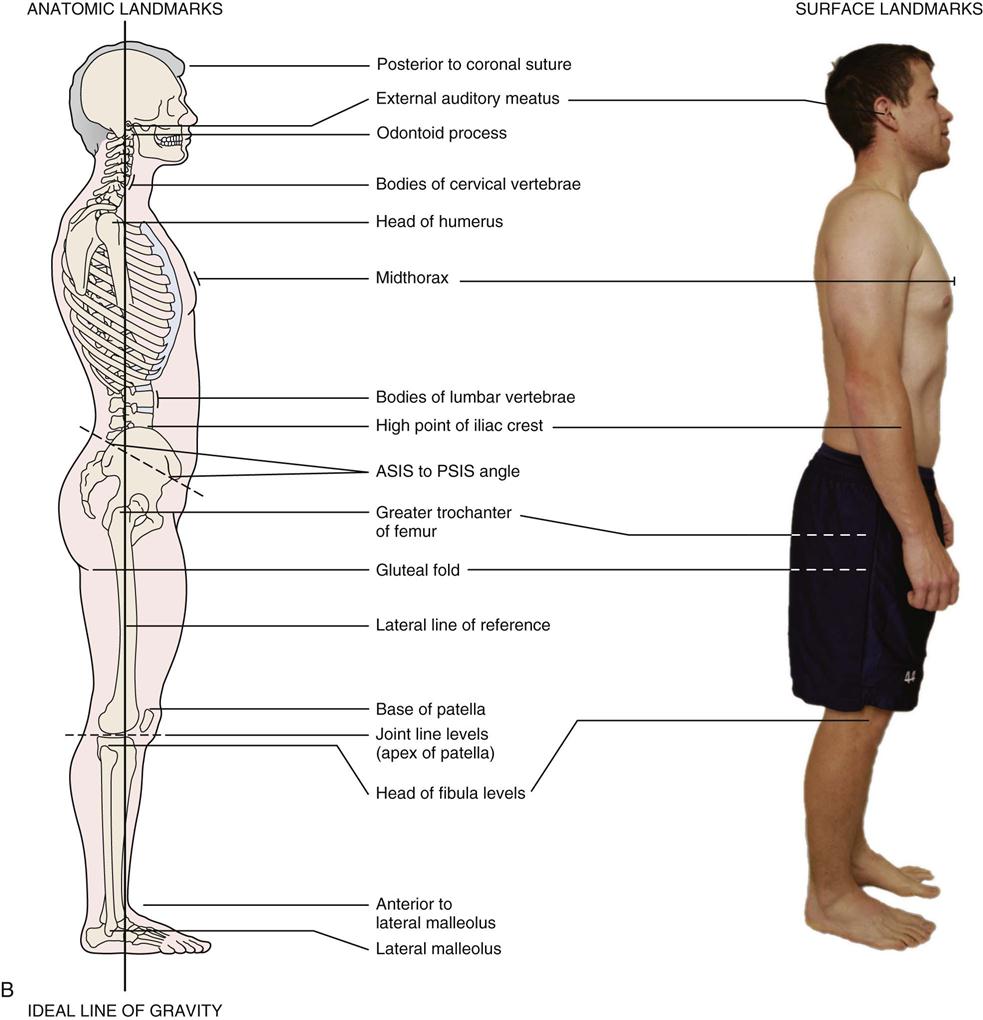

Posture, which is the relative disposition of the body at any one moment, is a composite of the positions of the different joints of the body at that time. The position of each joint has an effect on the position of the other joints. Classically, ideal static postural alignment (viewed from the side) is defined as a straight line (line of gravity) that passes through the earlobe, the bodies of the cervical vertebrae, the tip of the shoulder, midway through the thorax, through the bodies of the lumbar vertebrae, slightly posterior to the hip joint, slightly anterior to the axis of the knee joint, and just anterior to the lateral malleolus (Figure 15-1).1 Correct posture is the position in which minimum stress is applied to each joint. Upright posture is the normal standing posture for humans. Although upright posture allows one to see farther and provides freedom to move the arms, it does have disadvantages. It places greater stress on the lower limbs, pelvis, and spine; reduces stability; and increases the work of the heart.2 If the upright posture is correct, minimal muscle activity is needed to maintain the position.

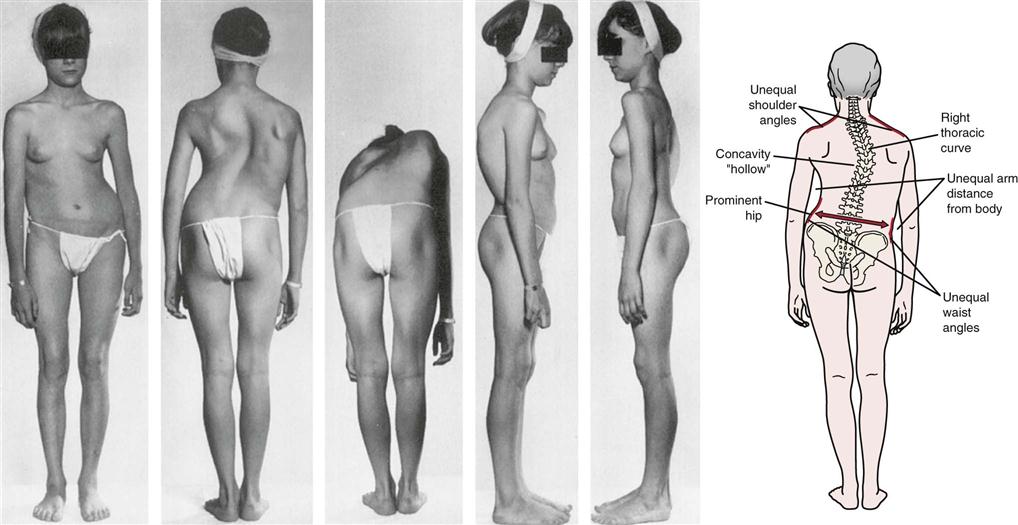

A, Front view. On a typical patient note the difference in shoulder height and nipple height and apparent arm length difference, arm-thorax difference, and difference in out-toeing. B, Side view. Typical patient with good lateral alignment. C, Back view. On a typical patient note the difference in shoulder slope, shoulder height, height of inferior scapular angles, and rotation of arms. In this view, also note straight Achilles tendons.

Any static position that increases the stress to the joints may be called faulty posture. If a person has strong, flexible muscles, faulty postures may not affect the joints because he or she has the ability to change position readily so that the stresses do not become excessive. If the joints are stiff (hypomobile) or too mobile (hypermobile), or the muscles are weak, shortened, or lengthened, however, the posture cannot be easily altered to the correct alignment, and the result can be some form of pathology. The pathology may be the result of the cumulative effect of repeated small stresses (microtrauma) over a long period of time or of constant abnormal stresses (macrotrauma) over a short period of time. These chronic stresses can result in the same problems that are seen when a sudden (acute) severe stress is applied to the body. The abnormal stresses cause excessive wearing of the articular surfaces of joints and produce osteophytes and traction spurs, which represent the body’s attempt to alter its structure to accommodate these repeated stresses. The soft tissue (e.g., muscles, ligaments) may become weakened, stretched, or traumatized by the increased stress. Thus postural deviations do not always cause symptoms, but over time, they may do so.3 The application of an acute stress on the chronic stress may exacerbate the problem and produce the signs and symptoms that initially prompt the patient to seek aid.

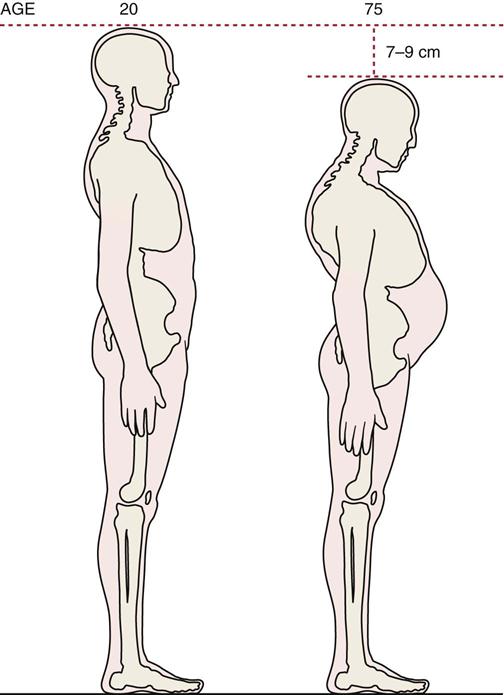

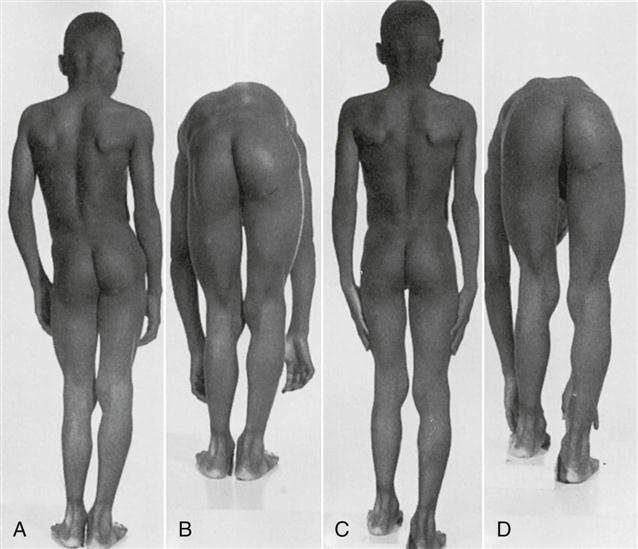

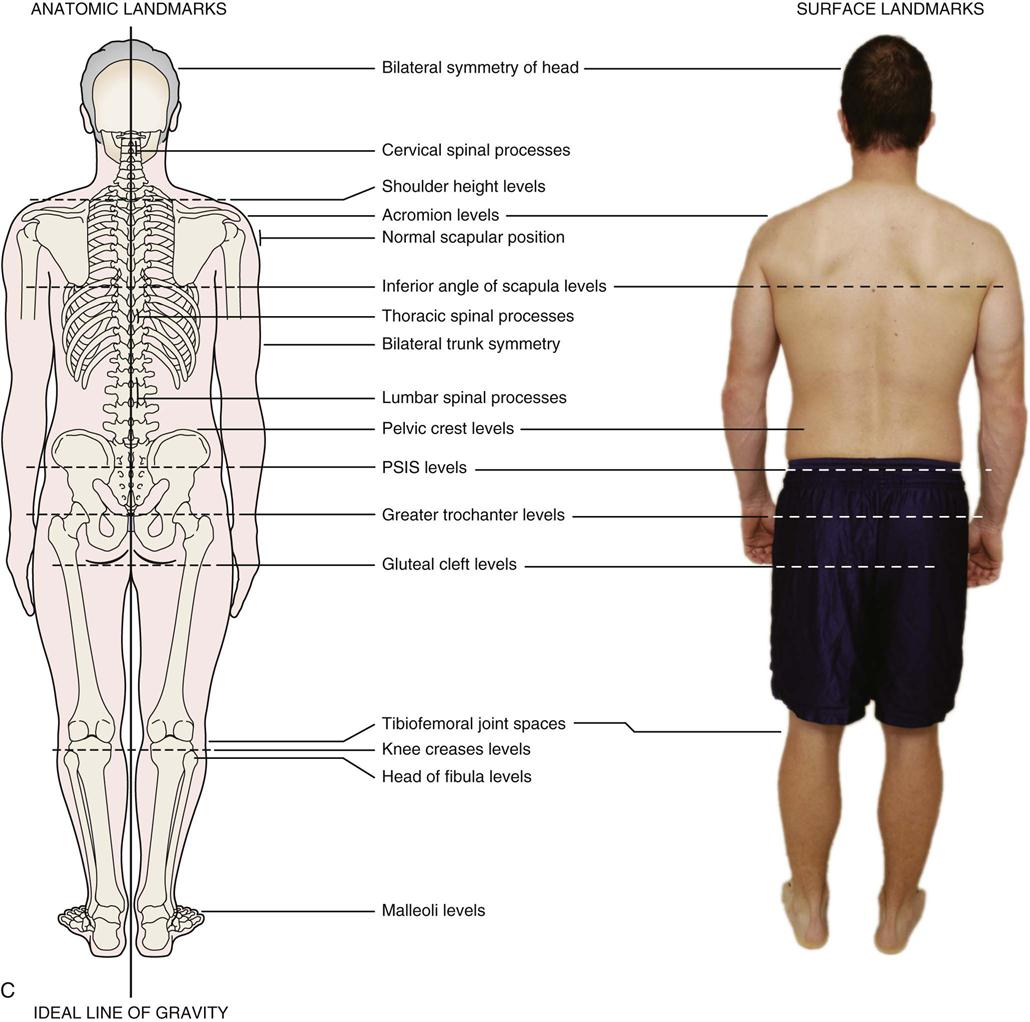

At birth, the entire spine is concave forward, or flexed (Figure 15-2). Curves of the spine found at birth are called primary curves. The curves that retain this position, those of the thoracic spine and sacrum, are therefore classified as primary curves of the spine. As the child grows (Figure 15-3), secondary curves appear and are convex forward, or extended. At about the age of 3 months, when the child begins to lift the head, the cervical spine becomes convex forward, producing the cervical lordosis. In the lumbar spine, the secondary curve develops slightly later (6 to 8 months), when the child begins to sit up and walk. In old age, the secondary curves again begin to disappear as the spine starts to return to a flexed position as the result of disc degeneration, ligamentous calcification, osteoporosis, and vertebral wedging.

A, Flexed posture in a newborn. B, Development of secondary cervical curve. C, Development of secondary lumbar curve. D, Sitting posture.

Apparent kyphosis at 6 and 8 years is caused by scapular winging. (From McMorris RO: Faulty postures. Pediatr Clin North Am 8:214, 1961.)

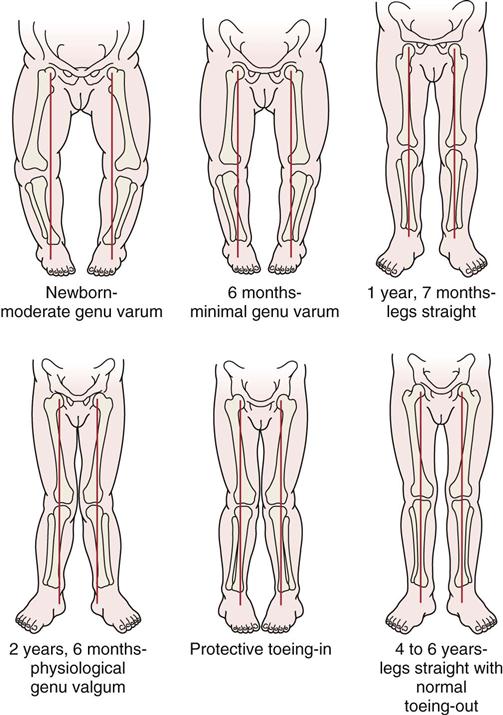

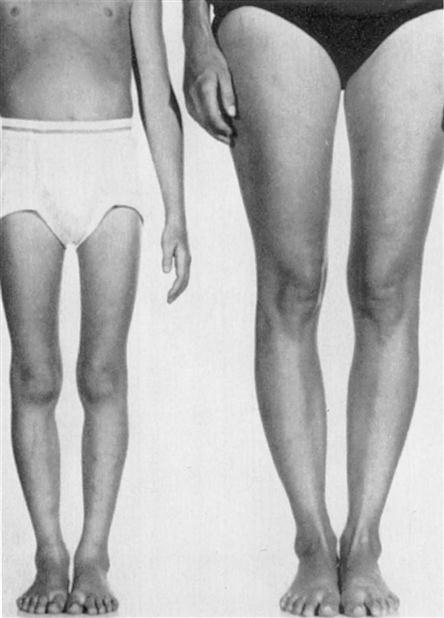

In the child, the center of gravity is at the level of the twelfth thoracic vertebra. As the child grows older, the center of gravity drops, eventually reaching the level of the second sacral vertebra in adults (slightly higher in males). The child stands with a wide base to maintain balance, and the knees are flexed. The knees are slightly bowed (genu varum) until about 18 months of age. The child then becomes slightly knock kneed (genu valgum) until the age of 3 years. By the age of 6 years, the legs should naturally straighten (Figure 15-4). The lumbar spine in the child has an exaggerated lumbar curve, or excessive lordosis. This accentuated curve is caused by the presence of large abdominal contents, weakness of the abdominal musculature, and the small pelvis characteristic of children at this age.

Initially, a child is flatfooted, or appears to be, as the result of the minimal development of the medial longitudinal arch and the fat pad that is found in the arch. As the child grows, the fat pad slowly decreases in size, making the medial arch more evident. In addition, as the foot develops and the muscles strengthen, the arches of the feet develop normally and become more evident.

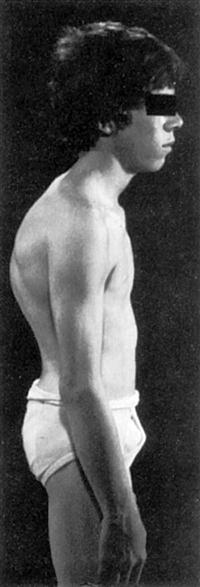

During adolescence, posture changes because of hormonal influence with the onset of puberty and musculoskeletal growth. Human beings go through two growth spurts, one when they are very young and a more obvious one when they are in adolescence. This second growth spurt lasts 2.5 to 4 years.4 During this period, growth is accompanied by sexual maturation. Females develop quicker and sooner than males. Females enter puberty between 8 and 14 years of age, and puberty lasts about 3 years. Males enter puberty between 9.5 and 16 years of age, and it lasts up to 5 years.2 It is during this period that body differences arise between males and females with males tending toward longer leg and arm length, wider shoulders, smaller hip width, and greater overall skeletal size and height than females. Because of the rapid growth spurt, individuals, especially males, may appear ungainly, and poor postural habits and changes are more likely to occur at this age.

Factors Affecting Posture

Several anatomical features may affect correct posture. These features may be enhanced or cause additional problems when combined with pathological or congenital states, such as Klippel-Feil syndrome, Scheuermann disease (juvenile kyphosis), scoliosis, or disc disease.

Causes of Poor Posture

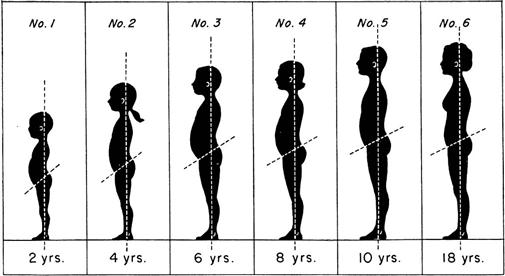

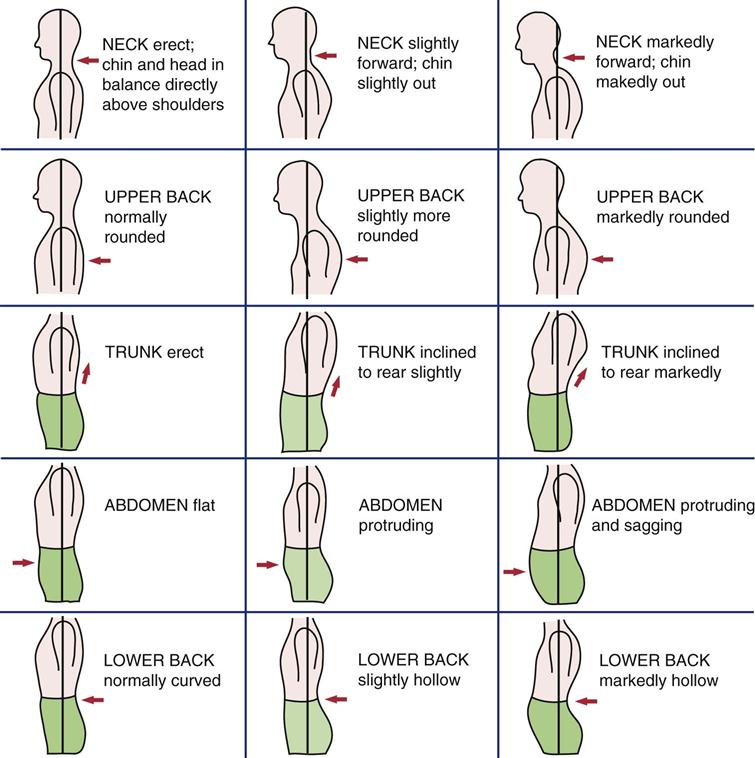

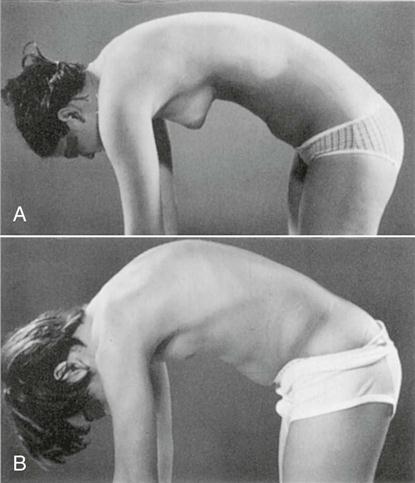

There are many examples of poor posture (Figure 15-5). Some of the causes are postural (positional), and some are structural.

Postural (Positional) Factors

The most common postural problem is poor postural habit; that is, for whatever reason, the patient does not maintain a correct posture. This type of posture is often seen in the person who stands or sits for long periods and begins to slouch. Maintenance of correct posture requires muscles that are strong, flexible, and easily adaptable to environmental change. These muscles must continually work against gravity and in harmony with one another to maintain an upright posture.

Another cause of poor postural habits, especially in children, is not wanting to appear taller than one’s peers. If a child has an early, rapid growth spurt there may be a tendency to slouch so as not to “stand out” and appear different. Such a spurt may also result in the unequal growth of the various structures, and this may lead to altered posture; for example, the growth of muscle may not keep up with the growth of bone. This process is sometimes evident in adolescents with tight hamstrings.

Muscle imbalance and muscle contracture are other causes of poor posture. For example, a tight iliopsoas muscle increases the lumbar lordosis in the lumbar spine.

Pain may also cause poor posture. Pressure on a nerve root in the lumbar spine can lead to pain in the back and result in a scoliosis as the body unconsciously adopts a posture that decreases the pain.

Respiratory conditions (e.g., emphysema), general weakness, excess weight, loss of proprioception, or muscle spasm (as seen in cerebral palsy or with trauma, as examples) may also lead to poor posture.

The majority of postural nonstructural faults are relatively easy to correct after the problem has been identified. The treatment involves strengthening weak muscles, stretching tight structures, and teaching the patient that it is his or her responsibility to maintain a correct upright posture in standing, sitting, and other activities of daily living (ADLs).

Structural Factors

Structural deformities that are the result of congenital anomalies, developmental problems, trauma, or disease may cause an alteration of posture. For example, a significant difference in leg length or an anomaly of the spine, such as a hemivertebra, may alter the posture.

Structural deformities involve mainly changes in bone and therefore are not easily correctable without surgery. However, patients often can be relieved of symptoms by proper postural care instruction.

Common Spinal Deformities

Lordosis

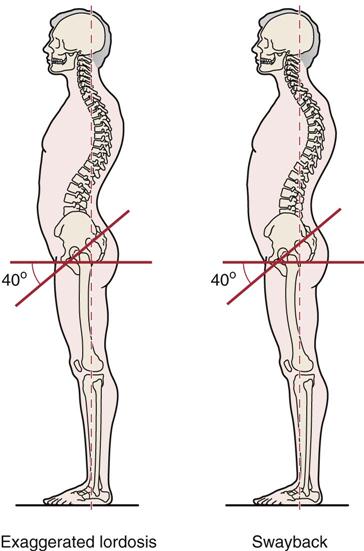

Lordosis is an anterior curvature of the spine (Figure 15-6).5–9 Pathologically, it is an exaggeration of the normal curves found in the cervical and lumbar spines. Causes of increased lordosis include (1) postural or functional deformity; (2) lax muscles, especially the abdominal muscles, in combination with tight muscles, especially hip flexors or lumbar extensors (Table 15-1); (3) a heavy abdomen, resulting from excess weight or pregnancy; (4) compensatory mechanisms that result from another deformity, such as kyphosis (Figure 15-7); (5) tight and commonly strong muscles (see Table 15-1); (6) spondylolisthesis; (7) congenital problems, such as bilateral congenital dislocation of the hip; (8) failure of segmentation of the neural arch of a facet joint segment; or (9) fashion (e.g., wearing high-heeled shoes). There are two types of exaggerated lordosis, pathological lordosis and swayback deformity.

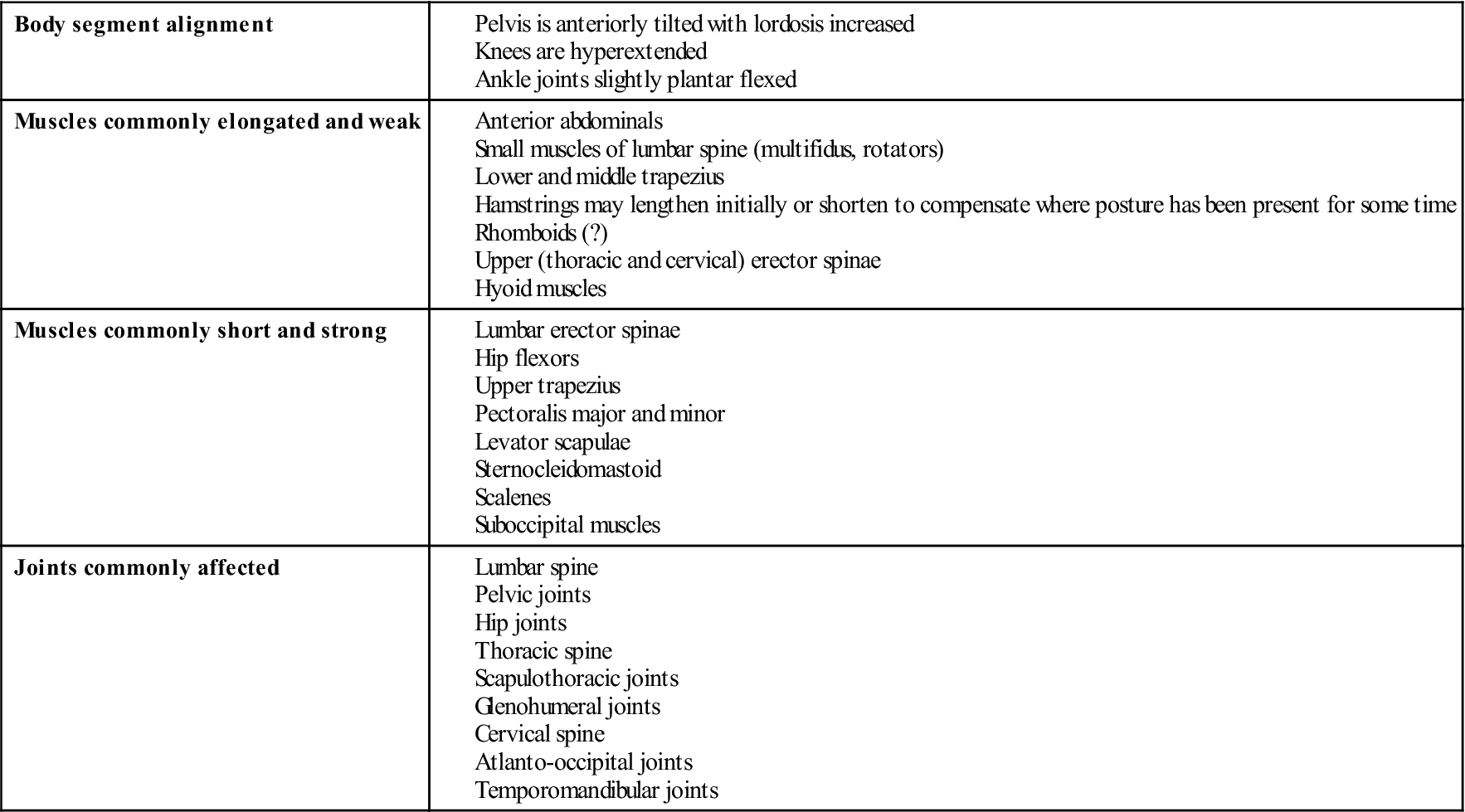

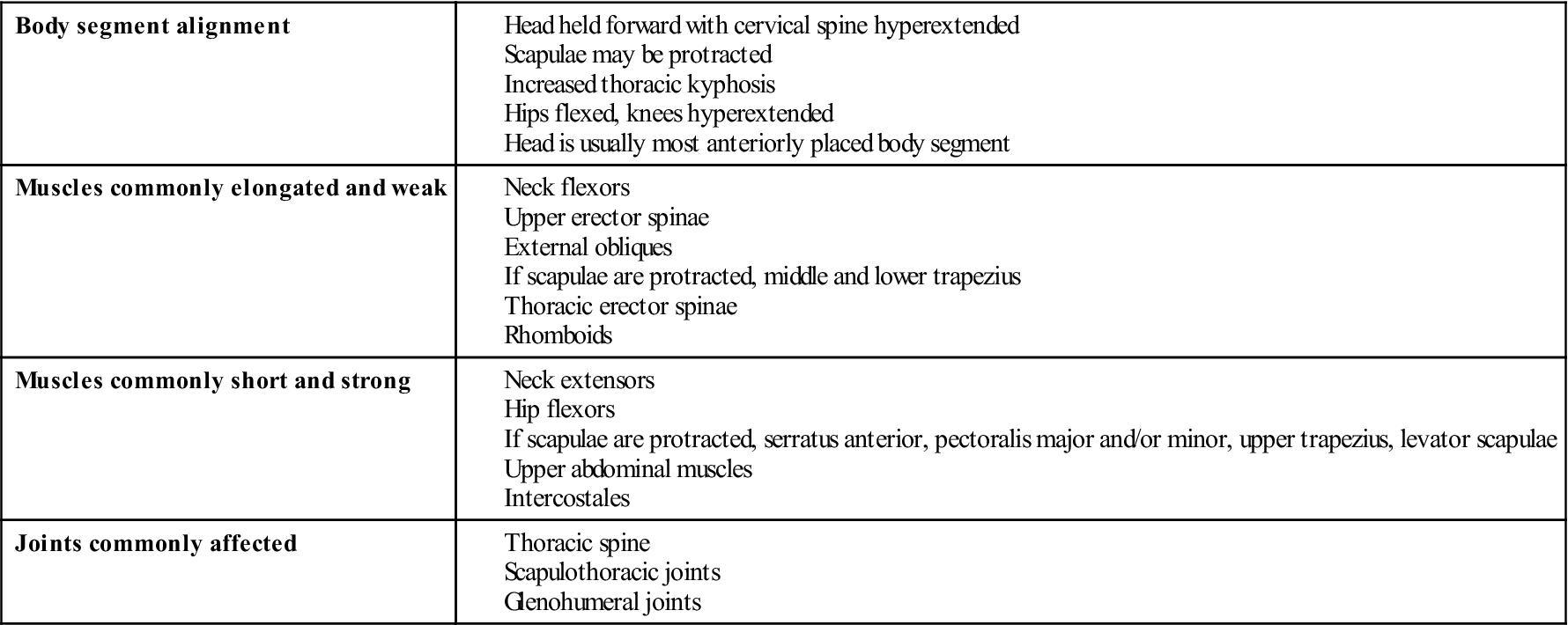

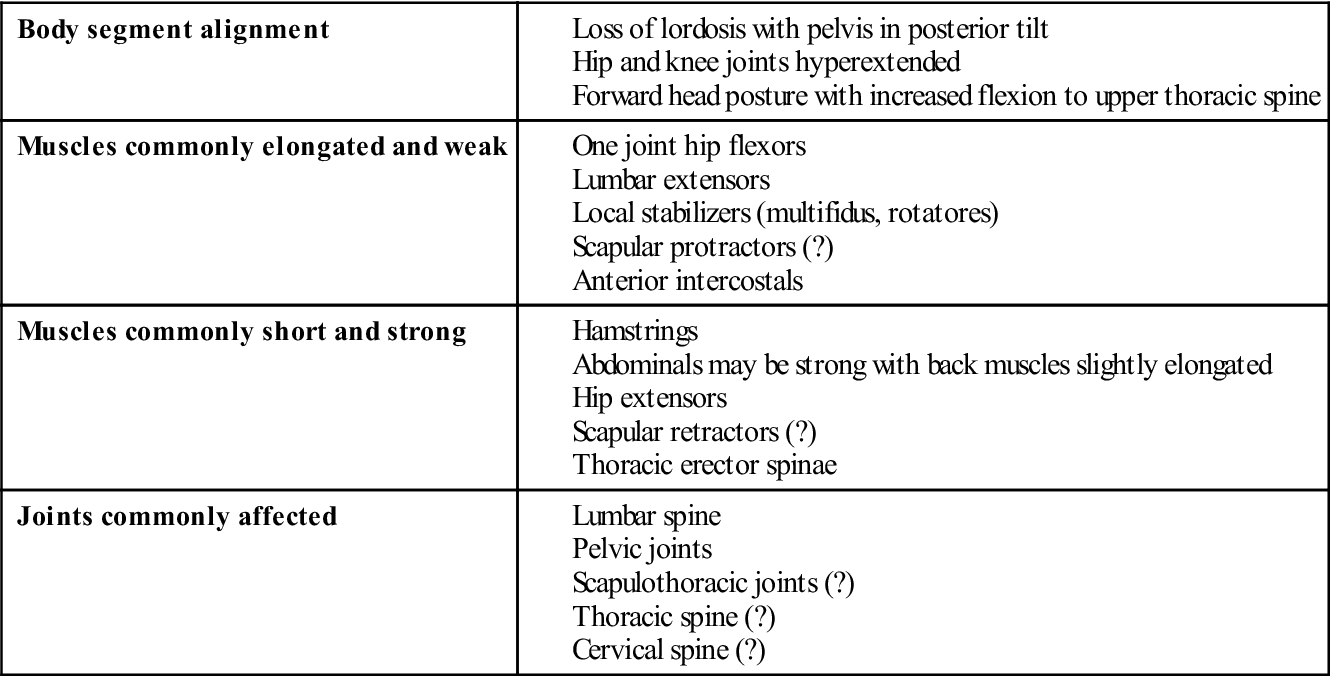

TABLE 15-1

Changes Associated with Pathological Lordosis

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Pathological Lordosis.

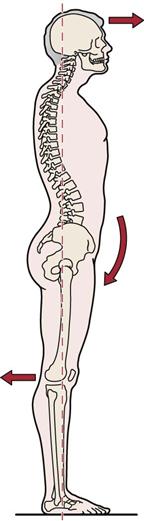

In the patient with pathological lordosis, one may often observe sagging shoulders (scapulae are protracted and arms are medially rotated), medial rotation of the legs, and poking forward of the head so that it is in front of the center of gravity (Figure 15-8). This posture is adopted in an attempt to keep the center of gravity where it should be. Deviation in one part of the body often leads to deviation in another part of the body in an attempt to maintain the correct center of gravity and the correct visual plane. This type of exaggerated lordosis is the most common postural deviation seen.

The pelvic angle, normally approximately 30°, is increased with lordosis. With excessive or pathological lordosis, there is an increase in the pelvic angle to approximately 40°, accompanied by a mobile spine and an anterior pelvic tilt. Exaggerated lumbar lordosis is usually accompanied by weakness of the deep lumbar extensors and tightness of the hip flexors and tensor fasciae latae combined with weak abdominals (see Table 15-1).10

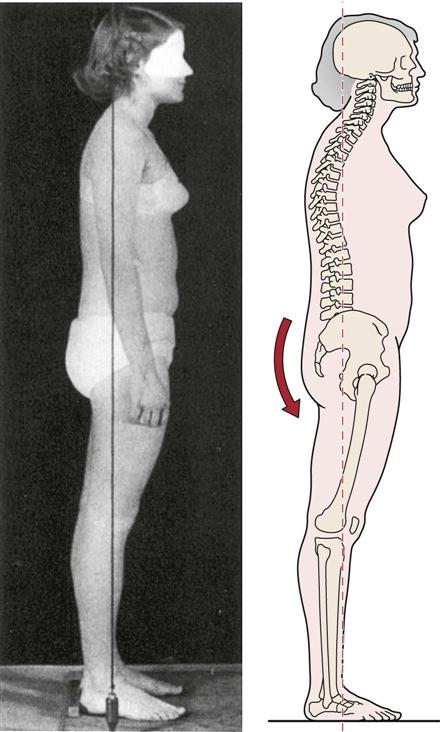

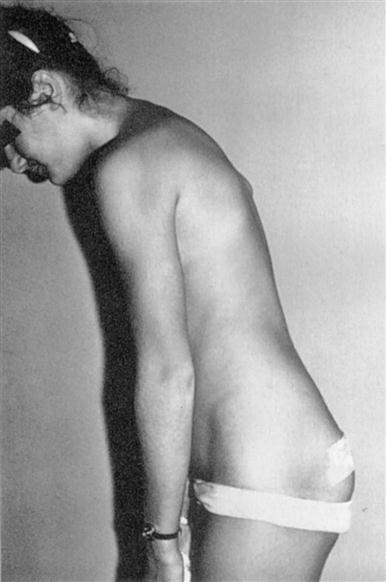

Swayback Deformity.

With a swayback deformity, there is increased pelvic inclination to approximately 40°, and the thoracolumbar spine exhibits a kyphosis (Figure 15-9). A swayback deformity results in the spine’s bending back rather sharply at the lumbosacral angle. With this postural deformity, the entire pelvis shifts anteriorly, causing the hips to move into extension. To maintain the center of gravity in its normal position, the thoracic spine flexes on the lumbar spine. The result is an increase in the lumbar and thoracic curves. Such a deformity may be associated with tightness of the hip extensors, lower lumbar extensors, and upper abdominals, along with weakness of the hip flexors, lower abdominals, and lower thoracic extensors (Table 15-2).1

TABLE 15-2

Changes Associated with Swayback

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Kyphosis

Kyphosis is a posterior curvature of the spine (Figures 15-10 and 15-11).7,9,11–15 Pathologically, it is an exaggeration of the normal curve found in the thoracic spine. There are several causes of kyphosis, including tuberculosis, vertebral compression fractures, Scheuermann disease, ankylosing spondylitis, senile osteoporosis, tumors, compensation in conjunction with lordosis, and congenital anomalies.11 The congenital anomalies include a partial segmental defect, as seen in osseous metaplasia, or centrum hypoplasia and aplasia.14,16,17 In addition, paralysis may lead to a kyphosis because of the loss of muscle action needed to maintain the correct posture combined with the forces of gravity.

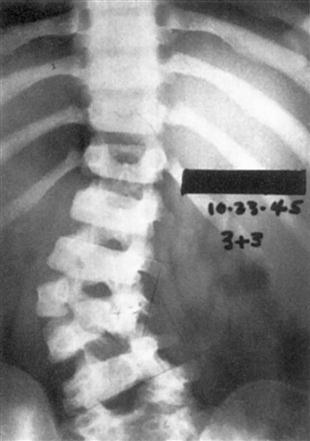

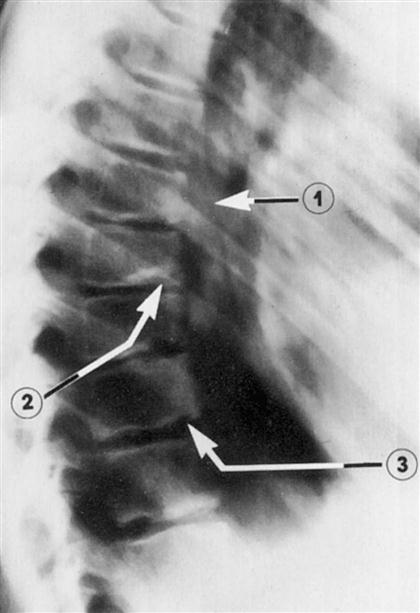

Pathological conditions, such as Scheuermann vertebral osteochondritis, may also result in a structural kyphosis (Figure 15-12 ). In this condition, inflammation of the bone and cartilage occurs around the ring epiphysis of the vertebral body. The condition often leads to an anterior wedging of the vertebra. It is a growth disorder that affects approximately 10% of the population, and in most cases several vertebrae are affected. The most common area for the disease to occur is between T10 and L2.

Note the wedged vertebra (1), Schmorl nodules (2), and marked irregularity of the vertebral end plates (3). (From Moe JH, Bradford DS, Winter RB, et al: Scoliosis and other spinal deformities, Philadelphia, 1978, WB Saunders, p. 332.)

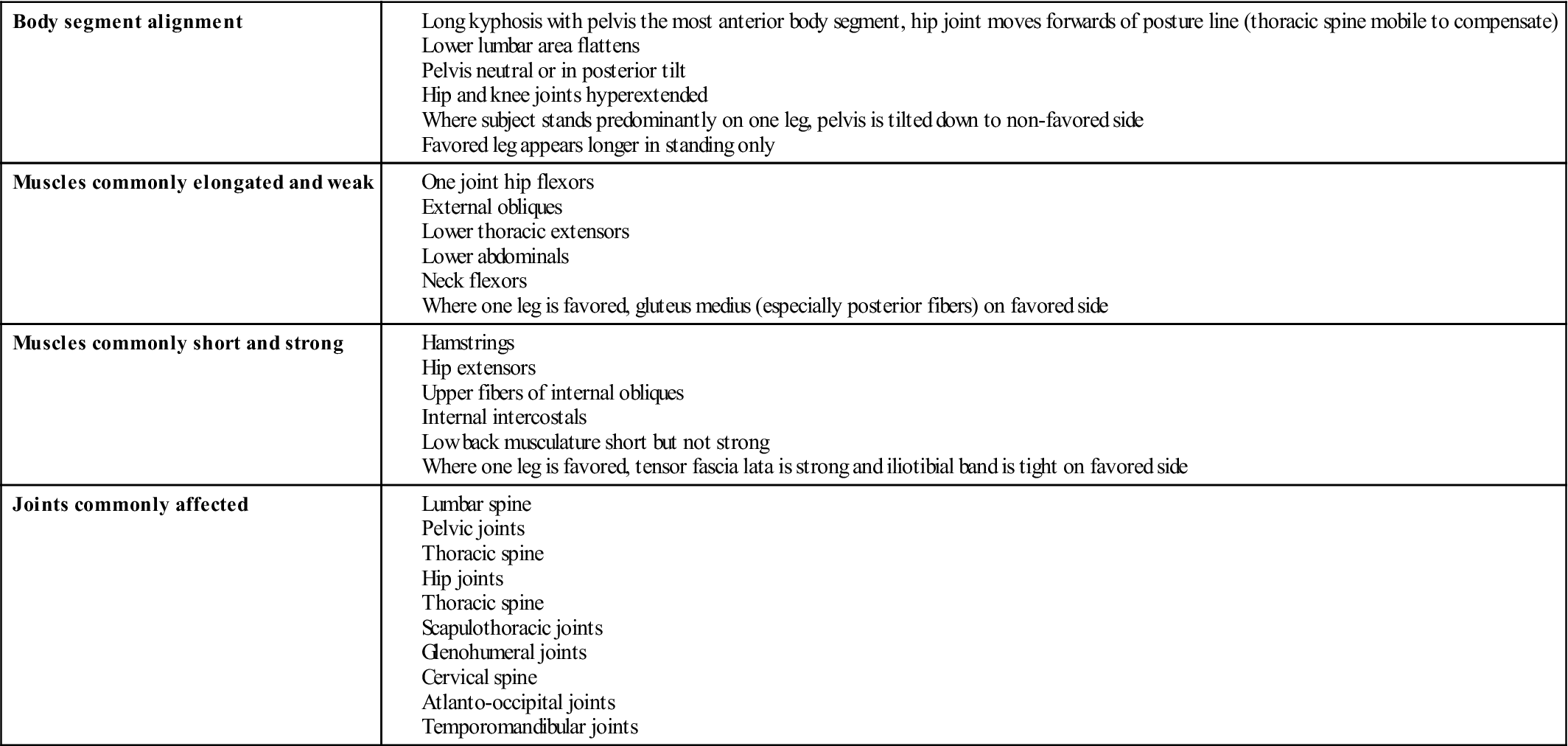

The four types of kyphosis are round back, humpback, flat back, and dowager’s hump.

Round Back.

The patient with a round back has a long, rounded curve with decreased pelvic inclination (less than 30°) and thoracolumbar kyphosis. The patient often presents with the trunk flexed forward and a decreased lumbar curve (Figure 15-13). On examination, there are tight hip extensors and trunk flexors with weak hip flexors and lumbar extensors (Table 15-3).

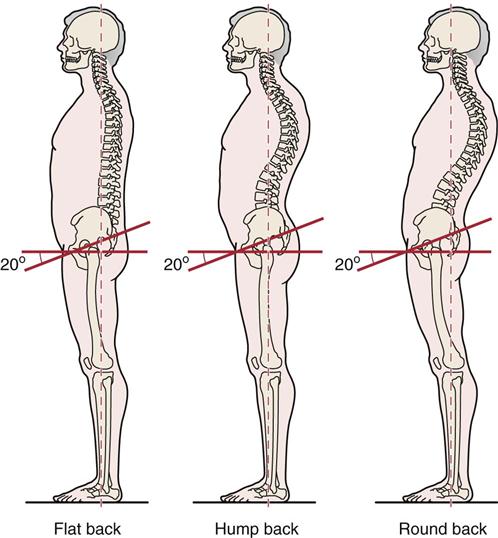

TABLE 15-3

Changes Associated with a Round Back Form of Kyphosis

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Humpback or Gibbus.

With humpback, there is a localized, sharp posterior angulation in the thoracic spine (Figure 15-14). This is commonly a structural deformity as the result of a fracture or pathology.

Flat Back.

A patient with flat back has decreased pelvic inclination to 20° and a mobile lumbar spine (Figure 15-15). Table 15-4 outlines the structures affected.

TABLE 15-4

Changes Associated with a Flat Back Form of Kyphosis

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

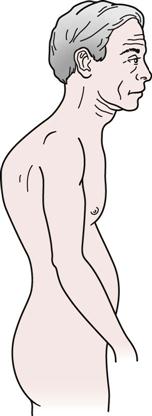

Dowager’s Hump.

Dowager’s hump is often seen in older patients, especially women. The deformity commonly is caused by osteoporosis, in which the thoracic vertebral bodies begin to degenerate and wedge in an anterior direction, resulting in a kyphosis (Figure 15-16).

Kypholordotic Posture.

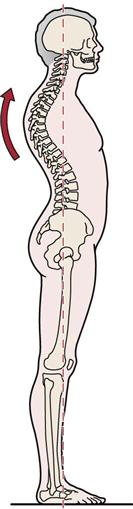

In some cases, both the thoracic and lumbar spine may be affected. Figure 15-17 and Table 15-5 outline the changes seen with this posture.

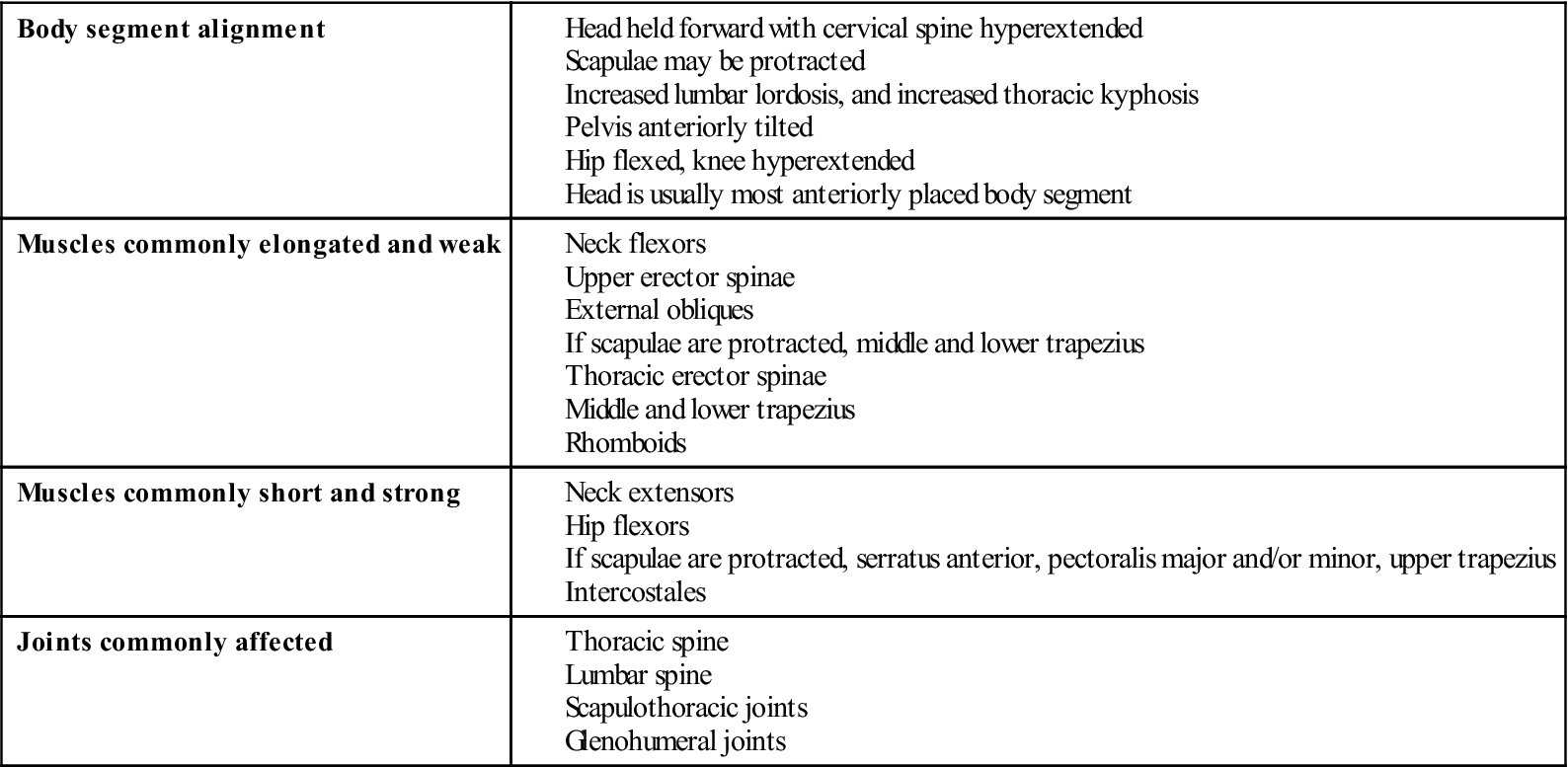

TABLE 15-5

Changes Associated with Kypholordotic Posture

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Scoliosis

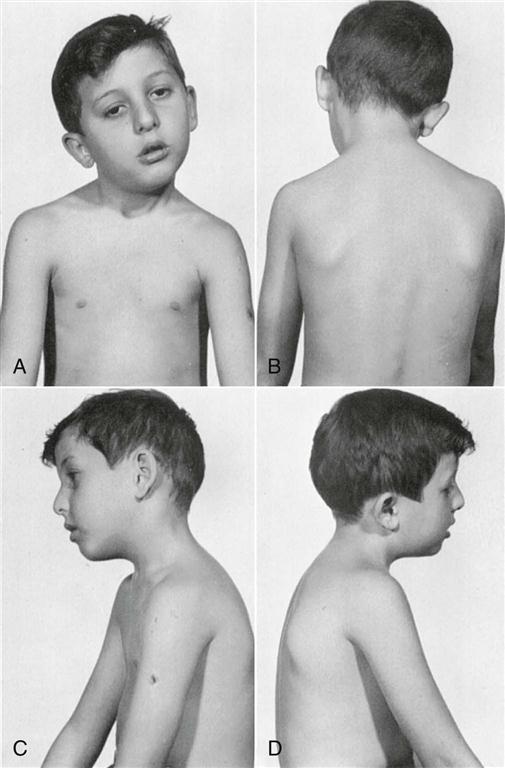

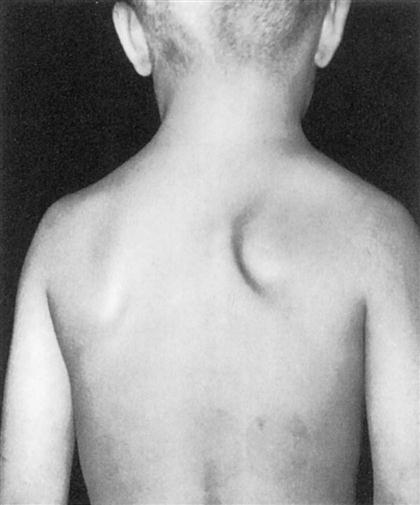

Scoliosis is a lateral curvature of the spine.11,13,18–24 This type of deformity is often the most visible spinal deformity, especially in its severe forms. The most famous example of scoliosis is the “hunchback of Notre Dame.” In the cervical spine, a scoliosis is called a torticollis. There are several types of scoliosis, some of which are nonstructural (Figure 15-18) and some of which are structural. Nonstructural or functional scoliosis may be caused by postural problems, hysteria, nerve root irritation, inflammation, or compensation caused by leg length discrepancy or contracture (in the lumbar spine) (Table 15-6).23 Structural scoliosis primarily involves bony deformity, which may be congenital or acquired, or excessive muscle weakness, as seen in a person with long-term quadriplegia. This type of scoliosis may be caused by wedge vertebra, hemivertebra (Figure 15-19), or failure of segmentation. It may be idiopathic (genetic) (Figure 15-20); neuromuscular, resulting from an upper or lower motor neuron lesion; or myopathic, resulting from muscular disease; or it may be caused by arthrogryposis, resulting from persistent joint contracture,17 or by conditions such as neurofibromatosis, mesenchymal disorders, or trauma. It may accompany infection, tumors, and inflammatory conditions that result in bone destruction. Torticollis may occur because of neuromuscular problems, because of congenital problems (abnormal sternocleidomastoid muscle), or in conjunction with malocclusion of the temporomandibular joints or with ear problems (referred to the cervical spine).

Note the contracted sternocleidomastoid muscle. (From Tachdjian MO: Pediatric orthopedics, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders, p. 74.)

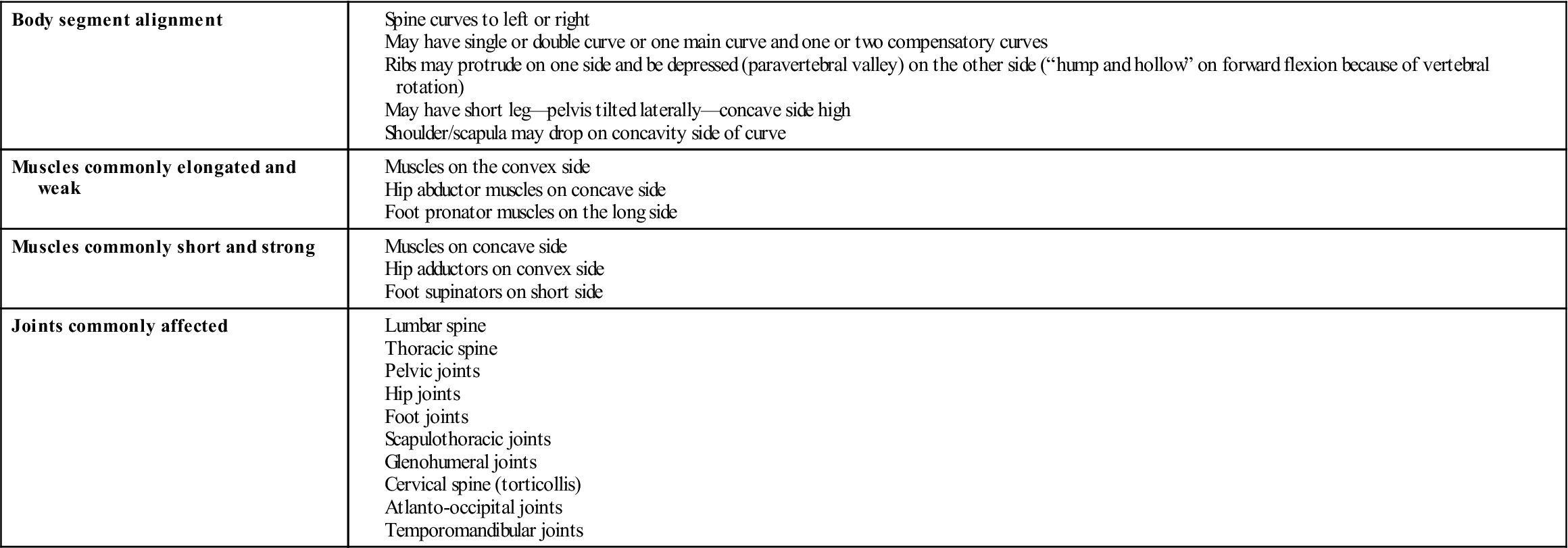

TABLE 15-6

Changes Associated with Postural Scoliosis

| Body segment alignment | |

| Muscles commonly elongated and weak | |

| Muscles commonly short and strong | |

| Joints commonly affected |

Adapted from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders.

Line drawing shows prominent features of scoliosis. (Photographs from Tachdjian MO: Pediatric orthopedics, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders, p. 1200.)

With structural scoliosis, the patient lacks normal flexibility, and side bending becomes asymmetrical. This type of scoliosis may be progressive, and the curve does not disappear on forward flexion. It is most commonly seen in the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine. With nonstructural scoliosis, there is no bony deformity; this type of scoliosis is not progressive. The spine shows segmental limitation, and side bending is usually symmetrical. The nonstructural scoliotic curve disappears on forward flexion. This type of scoliosis is usually found in the cervical, lumbar, or thoracolumbar area.

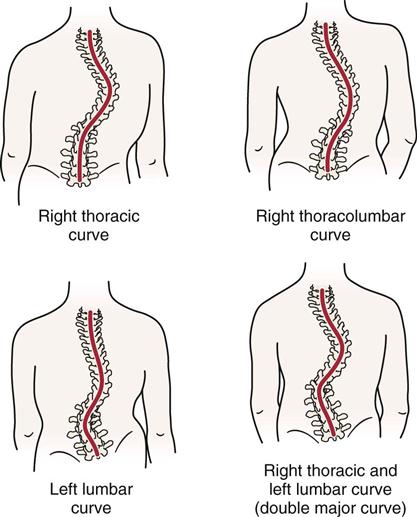

Idiopathic scoliosis accounts for 75% to 85% of all cases of structural scoliosis. The vertebral bodies rotate into the convexity of the curve with the spinous processes going toward the concavity of the curve. There is a fixed rotational prominence on the convex side, which is best seen on forward flexion from the skyline view. This prominence is sometimes called a “razorback spine.” The disc spaces are narrowed on the concave side and widened on the convex side. There is distortion of the vertebral body, and vital capacity is considerably lowered if the lateral curvature exceeds 60°; compression and malposition of the organs within the rib cage also occur. Examples of scoliotic curves are shown in Figure 15-21.

Patient History

As with any history, the examiner must ensure that the information obtained is as complete as possible. By listening to the patient, the examiner can often comprehend the problem. The information should include a history of the problem, the patient’s general condition and health, and family history. If a child is being examined, the examiner must also obtain prenatal and postnatal histories, including the health of or injuries experienced by the mother during pregnancy, any complications during pregnancy or delivery, and drugs taken by the mother during that period, especially during the first trimester, which is the period when most of the congenital anomalies develop.

It should be remembered that it is unusual for a patient to present with just a postural problem. It is the symptoms produced by the pathology that is causing the postural abnormality that initiate the consultation. The examiner therefore must be cognizant of various underlying pathological conditions when assessing posture.

The following questions should be asked:

3. Are there any postures (e.g., standing with one foot on low stool, sitting with legs crossed) that give the patient relief or increase the patient’s symptoms?25 The examiner can later test these postures to help determine the problem.

5. Has the patient had any previous illnesses, surgery, or severe injuries?

7. Does footwear make a difference to the patient’s posture or symptoms? For example, high-heeled shoes often lead to excessive lordosis.26

12. If a deformity is present, is it progressive or stationary?

14. What is the nature, extent, type, and duration of the pain?

15. What positions or activities increase the pain or discomfort?

16. What positions or activities decrease the pain or discomfort?

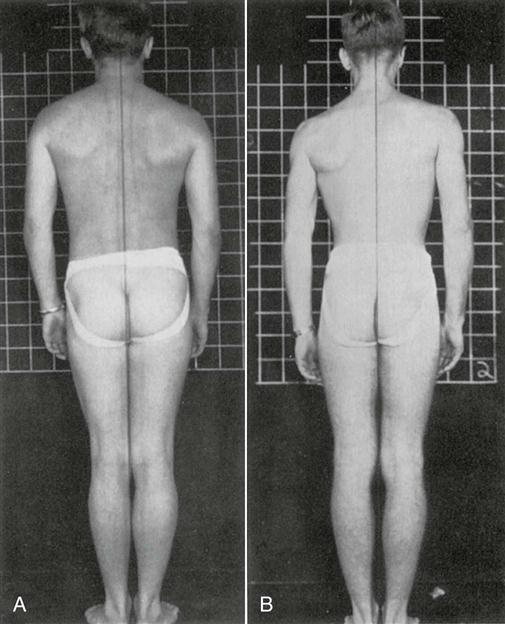

19. Which hand is the dominant one? Often, the dominant side shows a lower shoulder with the hip slightly deviated to that side (Figure 15-22). The spine may deviate slightly to the opposite side, and the opposite foot is slightly more pronated.7 The gluteus medius on the dominant side may also be weaker.

20. Has there been any previous treatment? If so, what was it? Was it successful?

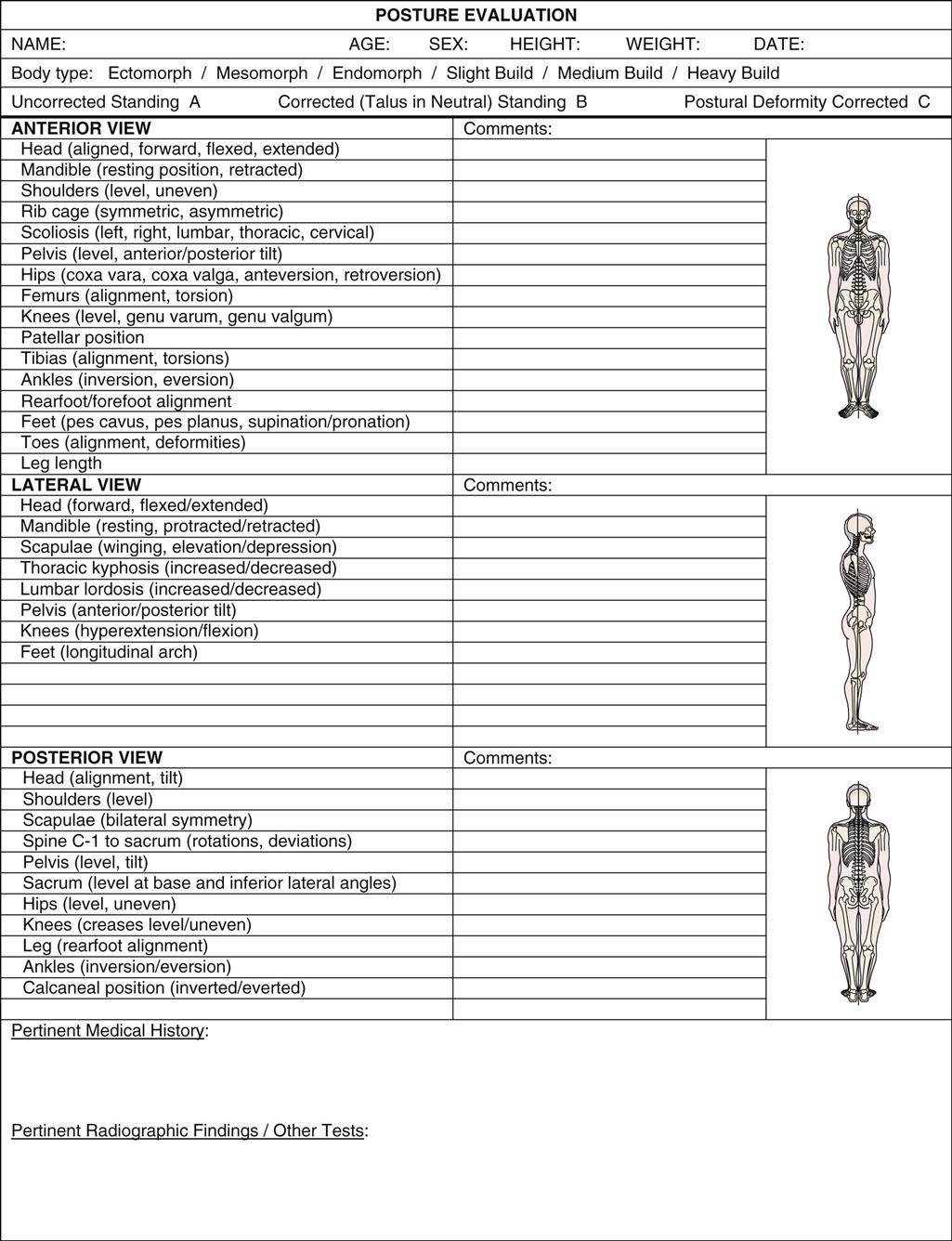

Observation

Observation is the primary method of assessing posture and should be included in every assessment, looking for asymmetrical changes that may contribute to or be the result of faulty posture. The following sections outline static posture, which forms the basis of dynamic posture (e.g., walking, running, lifting, throwing).2

To assess posture correctly, the patient must be adequately undressed. Male patients should be in shorts, and female patients should be in a bra and shorts. Ideally, the patient should not wear shoes or stockings. However, if the patient uses walking aids, braces, collars, or orthotics, they should be noted and may be used after the patient has been assessed in the “natural” state to determine the effect of the appliances.

The patient should be examined in the habitual, relaxed posture that is usually adopted. Often, it takes some time for the patient to adopt the usual posture because of tenseness, uneasiness, or uncertainty.

In the standing and sitting positions, the assessment is the same as the observation for the upper and lower limb scanning examinations of the cervical and lumbar spines. Assessment of posture should be carried out with the patient in the standing, sitting, and lying (supine and prone) positions. After the patient has been examined in these positions, the examiner may decide to include other habitual, sustained, or repetitive postures assumed by the patient to see whether these postures increase or alter symptoms. The patient may also be assessed wearing different footwear to determine their effects on the posture and symptoms.

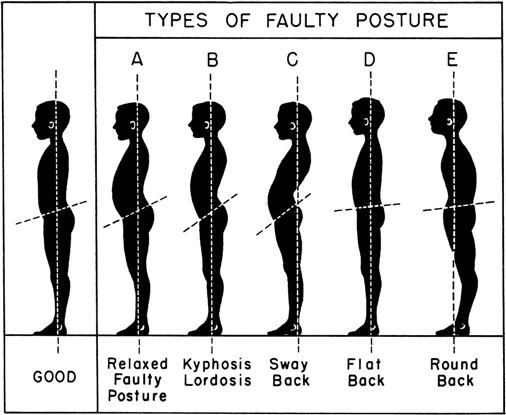

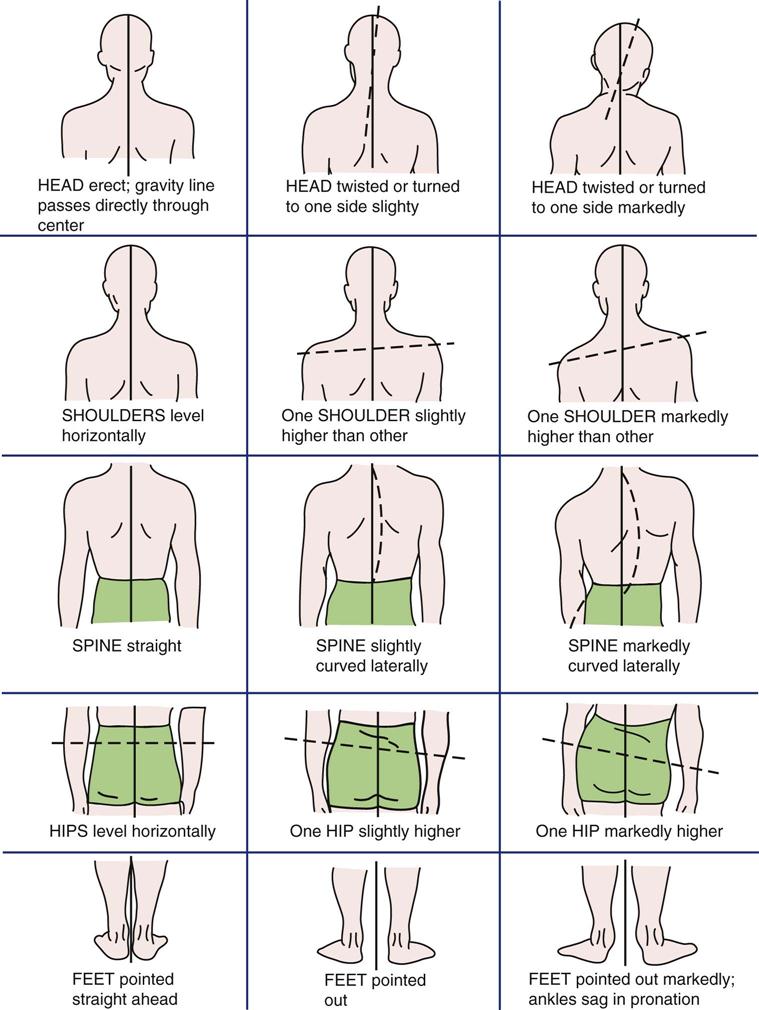

When observing a patient for abnormalities in posture, the examiner looks for asymmetry as a possible indication of what may be causing the postural fault (Figure 15-23). Some asymmetry between left and right sides is normal. The examiner must be able to differentiate normal deviations from asymmetry caused by pathology. Functional asymmetries usually refer to changes in alignment that occur with changes in posture. For example, nonstructural scoliosis may be present in standing because of a short leg but disappear on forward flexion. Anatomical or structural asymmetries are due to structural changes (e.g., idiopathic scoliosis).

Information is obtained by visual observation and palpation. (Modified from Richardson JK, Iglarsh ZA: Clinical orthopedic physical therapy, Philadelphia, 1994, WB Saunders.)

As the examiner is watching for asymmetry, he or she should also note potential causes of asymmetry. For example, the examiner should always watch for the presence of muscle wasting, soft tissue or bony swelling or enlargement, scars, and skin changes that may indicate present or past pathology.

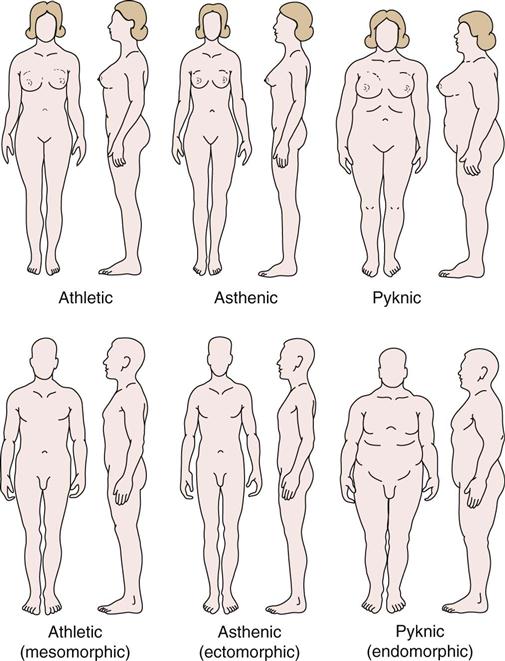

Standing

The examiner should first determine the patient’s body type (Figure 15-24).25 The three body types are ectomorphic, mesomorphic, and endomorphic. The ectomorph is a person who has a thin body build characterized by a relative prominence of structures developed from the embryonic ectoderm. The mesomorph has a muscular or sturdy body build characterized by relative prominence of structures developed by the embryonic mesoderm. The endomorph has a heavy or fat body build characterized by relative prominence of structures developed from the embryonic endoderm.

In addition to body type, the examiner should note the emotional attitude of the patient. Is the patient tense, bored, or lethargic? Does the patient appear to be healthy, emaciated, or overweight? Answers to these questions can help the examiner determine how much must be done to correct any problems. For example, if the patient is lethargic, it may take longer to correct the problem than if he or she appears truly interested in correcting the problem. The examiner must remember that posture is in many ways an expression of one’s personality, sense of well-being, and self-esteem.

Anterior View

When observing the patient from the front (Table 15-7; see Figure 15-1, A), the examiner should note whether the following conditions hold true:

1. The head is straight on the shoulders (in midline). The examiner should note whether the head is habitually tilted to one side or rotated (e.g., torticollis) (Figure 15-25). The cause of altered head position must be established. For example, it may be the result of weak muscles, trauma, a hearing loss, temporomandibular joint problems, or the wearing of bifocal glasses.

3. The tip of the nose is in line with the manubrium sternum, xiphisternum, and umbilicus. This line is the anterior line of reference used to divide the body into right and left halves (see Figure 15-1, A). If the umbilicus is used as a reference point, the examiner should remember that the umbilicus is almost always slightly off center.

5. The shoulders are level. In most cases, the dominant side is slightly lower.

11. The “high points” of the iliac crest are the same height on each side (Figure 15-26). With a scoliosis, the patient may feel that one hip is “higher” than the other. This apparent high pelvis results from the lateral shift of the trunk; the pelvis is usually level. The same condition can cause the patient to feel that one leg is shorter than the other.

13. The pubic bones are level at the symphysis pubis. Any deviation should be noted.

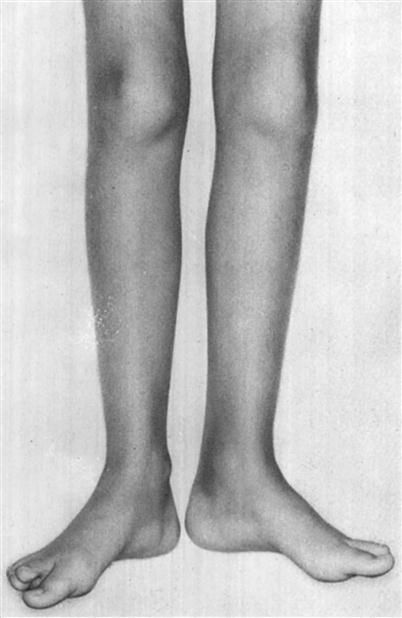

15. The knees are straight. The knees may be in genu varum or genu valgum. If the ankles are together and the knees are more than two finger-widths apart, the patient has some genu varum. If the knees are touching and the feet are apart, the patient has some genu valgum. Genu valgum is more likely to be seen in females. The examiner should note whether the deformity results from the femur, tibia, or both. In children, the knees go through a progression of being straight, going into genu varum (Figure 15-27), being straight, going into genu valgum (Figure 15-28), and finally being straight again during the first 6 years of life (see Figure 15-4).13

16. The heads of the fibulae are level.

19. The feet angle out equally (this Fick angle is usually 5° to 18° [see Figure 14-14]; Figure 15-29). This finding means that the tibias are normally slightly laterally rotated (lateral tibial torsion). The presence of pigeon toes usually indicates medial rotation of the tibias (medial tibial torsion), especially if the patellae face straight ahead. If the patellae face inward (squinting patellae) in the presence of “pigeon toes” or outward, the problem may be in the femur (abnormal femoral torsion or hip retroversion-anteversion problems).

20. There is no bowing of bone. Any bowing may indicate diseases, such as osteomalacia or osteoporosis.

Note the asymmetry of the face. (From Tachdjian MO: Pediatric orthopedics, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders, p. 68.)

Note the associated medial tibial torsion. (From Tachdjian MO: Pediatric orthopedics, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders, p. 1462.)

In stance, with the patellae facing straight forward, the feet point outward. (From Tachdjian MO: Pediatric orthopedics, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders, p. 1461.)

TABLE 15-7

Alignment in the Standing Posture: Anterior View

| Body Segment | Line of Gravity Location | Observation |

| Head | Passes through middle of the forehead, nose and chin | Eyes and ears should be level and symmetrical |

| Neck/shoulders | Right and left angles between shoulders and neck should be symmetrical; clavicles also should be symmetrical | |

| Chest | Passes through the middle of the xyphoid process | Ribs on each side should be symmetrical |

| Abdomen/hips | Passes through the umbilicus (navel) | Right and left waist angles should be symmetrical |

| Hips/pelvis | Passes on a line equidistant from the right and left ASISs; passes through the symphysis pubis | ASISs should be level |

| Knees | Passes between knees equidistant from medial femoral condyles | Patella should be symmetrical and facing straight ahead |

| Ankles/feet | Passes between ankles equidistant from the medial malleoli | Malleoli should be symmetrical, and feet should be parallel; toes should not be curled, overlapping, or deviated to one side |

ASIS, Anterior superior iliac spine.

From Levangie PK, Norkin CC: Joint structures and function—a comprehensive analysis, Philadelphia, 2005, FA Davis, p. 498.

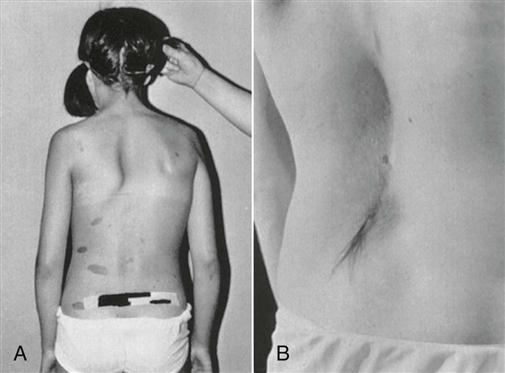

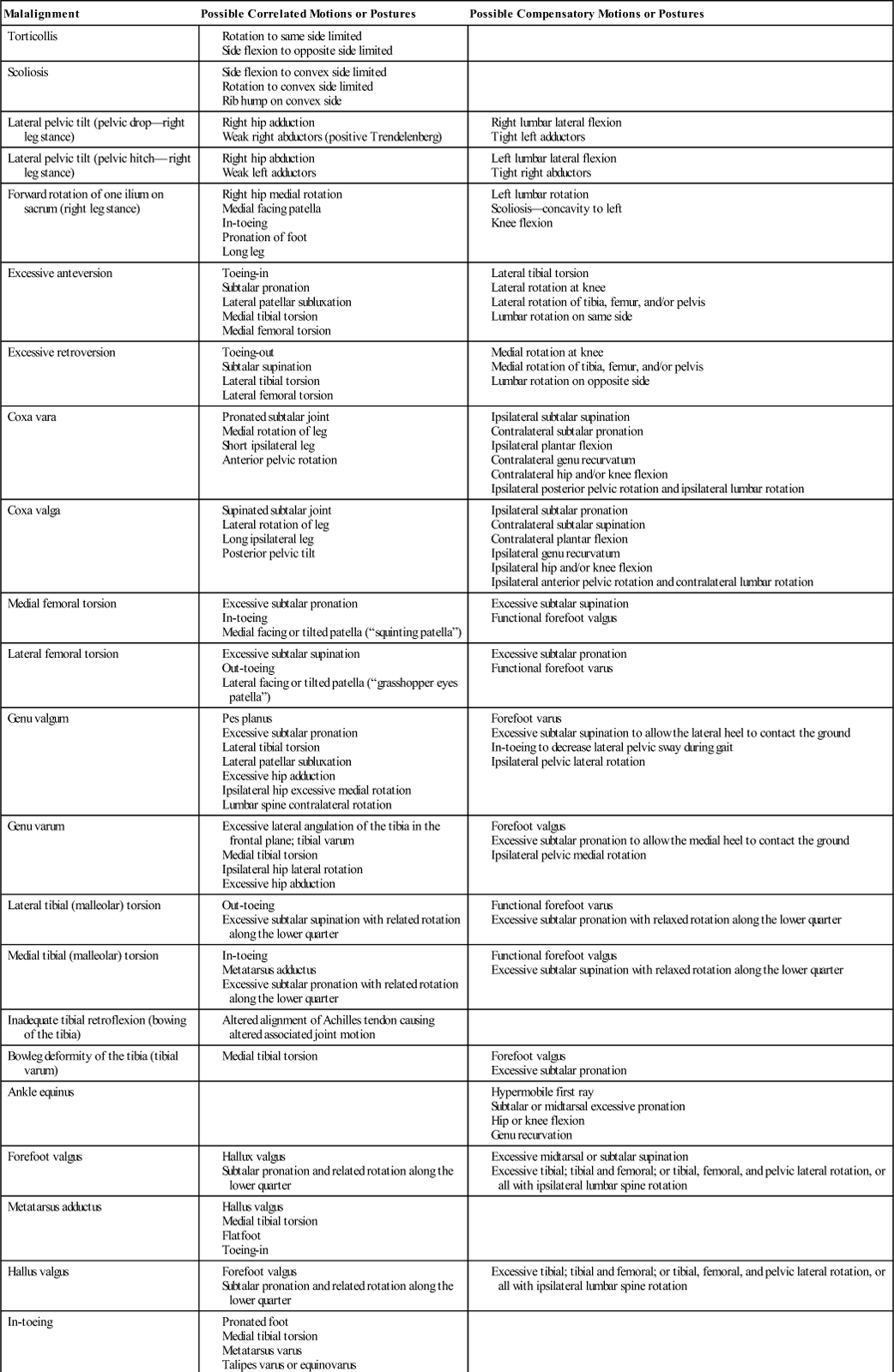

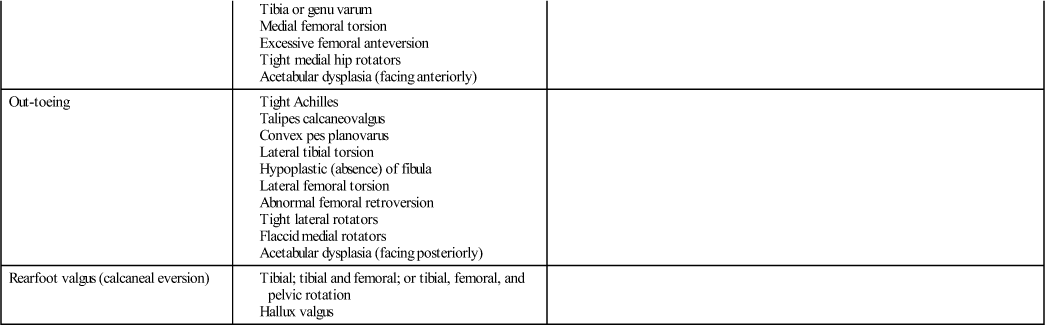

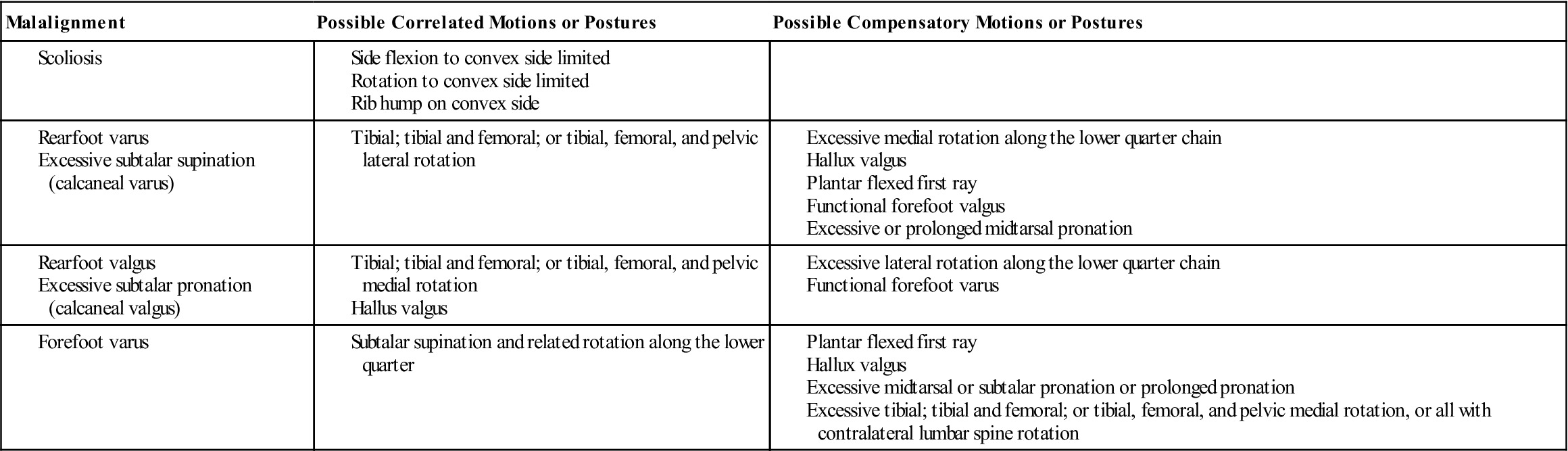

In addition, the patient’s skin is observed for abnormalities, such as hairy patches (e.g., diastematomyelia), pigmented lesions (e.g., café au lait spots, neurofibromatosis), subcutaneous tumors, and scars (e.g., Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), all of which may lead to or contribute to postural problems (Figure 15-30). Table 15-8 shows some of the malalignment postures and their effect.2,13,27,28 Changes in one body segment cause changes in other segments as the body attempts to compensate or adjust for the malignment.2 Compensatory postures are those that represent the body’s attempt to normalize appearance or improve function.2

A, Café au lait areas of pigmentation seen in neurofibromatosis. B, Lumbar hair patch seen in diastematomyelia. (From Moe JH, Bradford DS, Winter RB, et al: Scoliosis and other spinal deformities, Philadelphia, 1978, WB Saunders, p. 20.)

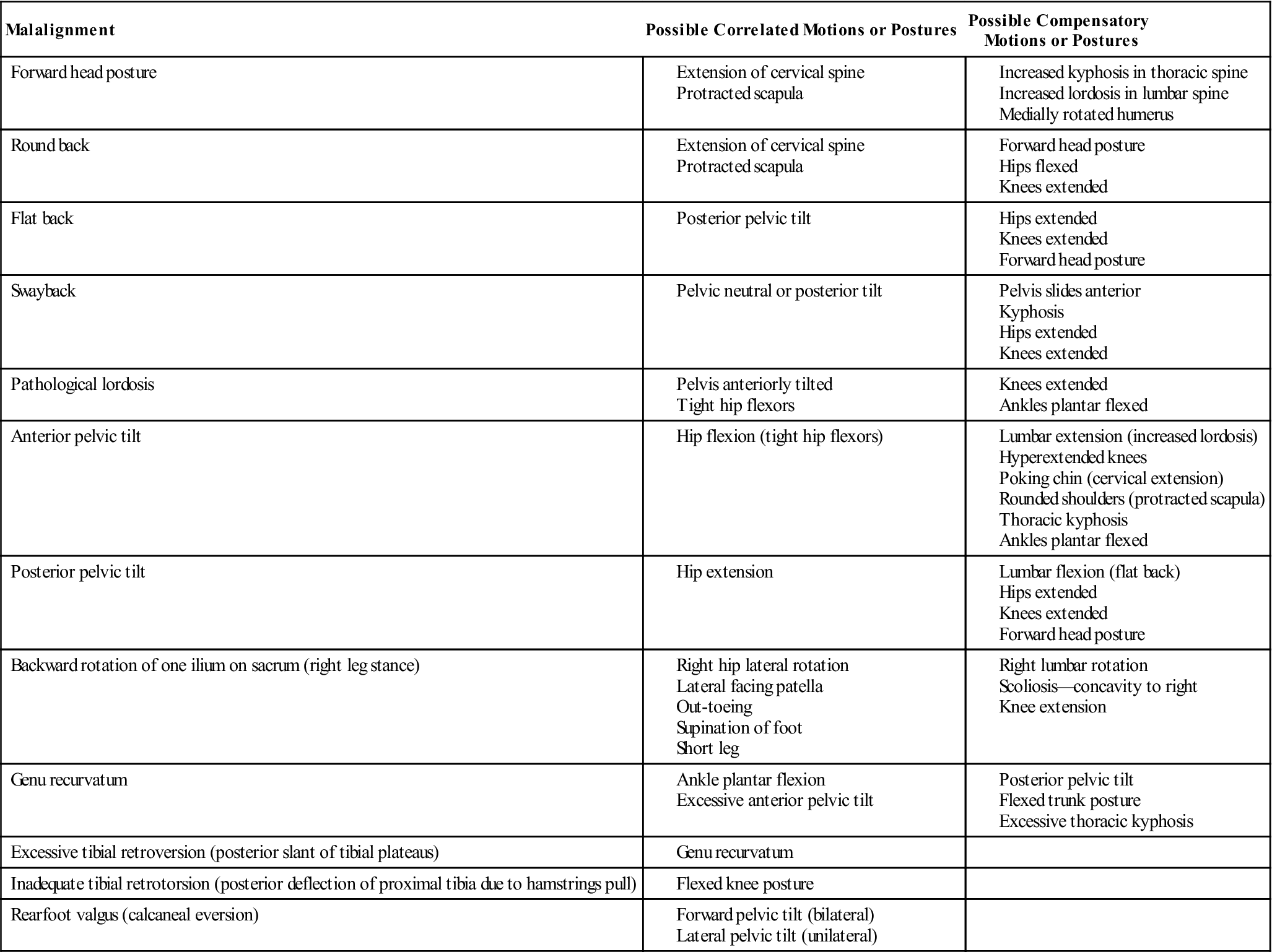

TABLE 15-8

Malalignments Viewed Anteriorly2,13,27,28

Lateral View

From the side (Table 15-9; see Figure 15-1, B), the examiner should note whether the following conditions hold true:

1. The earlobe is in line with the tip of the shoulder (acromion process) and the “high point” of the iliac crest. This line is the lateral line of reference dividing the body into front and back halves (see Figure 15-1, B). If the chin pokes forward, an excessive lumbar lordosis may also be present. This compensatory change is caused by the body’s attempt to maintain the center of gravity in the normal position.

2. Each spinal segment has a normal curve (Figure 15-31). Large gluteus maximus muscles or excessive fat may give the appearance of an exaggerated lordosis. The examiner should look at the spine in relation to the sacrum, not the gluteal muscles. Likewise, the scapulae may give the illusion of an increased kyphosis in the thoracic spine, especially if they are flat and the patient has rounded shoulders.

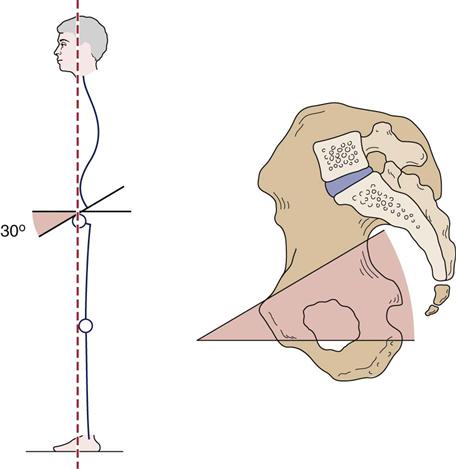

6. The pelvic angle is normal (30°; Figure 15-32). The posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) should be slightly higher than the ASIS.

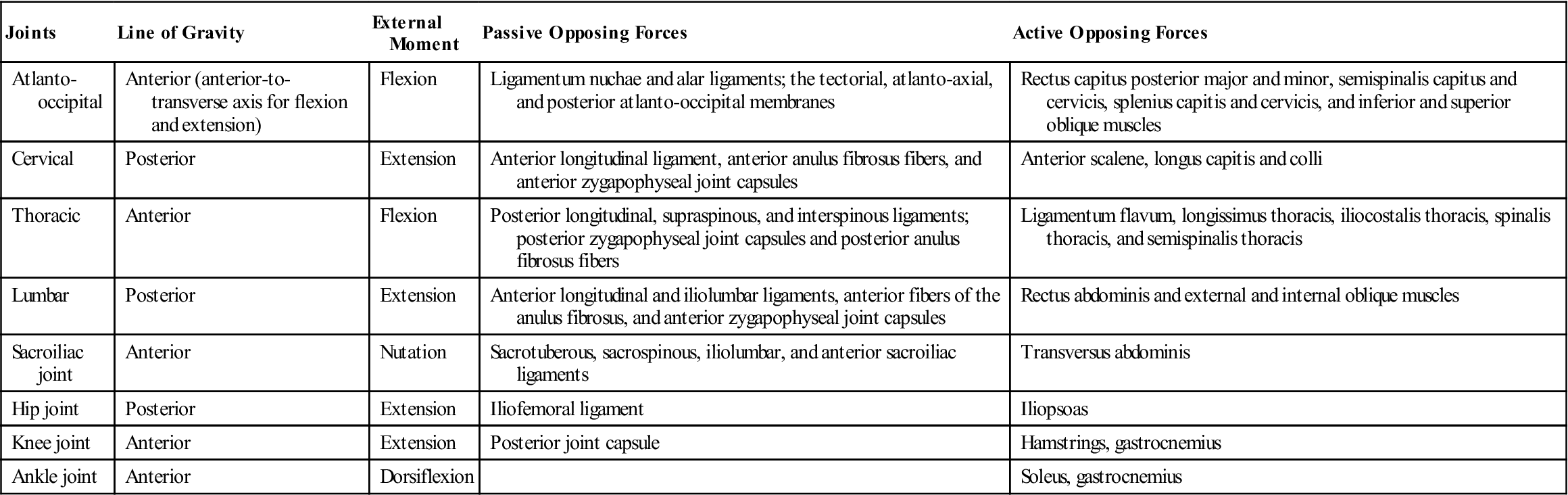

TABLE 15-9

Alignment in the Standing Posture: Side View

| Joints | Line of Gravity | External Moment | Passive Opposing Forces | Active Opposing Forces |

| Atlanto-occipital | Anterior (anterior-to-transverse axis for flexion and extension) | Flexion | Ligamentum nuchae and alar ligaments; the tectorial, atlanto-axial, and posterior atlanto-occipital membranes | Rectus capitus posterior major and minor, semispinalis capitus and cervicis, splenius capitis and cervicis, and inferior and superior oblique muscles |

| Cervical | Posterior | Extension | Anterior longitudinal ligament, anterior anulus fibrosus fibers, and anterior zygapophyseal joint capsules | Anterior scalene, longus capitis and colli |

| Thoracic | Anterior | Flexion | Posterior longitudinal, supraspinous, and interspinous ligaments; posterior zygapophyseal joint capsules and posterior anulus fibrosus fibers | Ligamentum flavum, longissimus thoracis, iliocostalis thoracis, spinalis thoracis, and semispinalis thoracis |

| Lumbar | Posterior | Extension | Anterior longitudinal and iliolumbar ligaments, anterior fibers of the anulus fibrosus, and anterior zygapophyseal joint capsules | Rectus abdominis and external and internal oblique muscles |

| Sacroiliac joint | Anterior | Nutation | Sacrotuberous, sacrospinous, iliolumbar, and anterior sacroiliac ligaments | Transversus abdominis |

| Hip joint | Posterior | Extension | Iliofemoral ligament | Iliopsoas |

| Knee joint | Anterior | Extension | Posterior joint capsule | Hamstrings, gastrocnemius |

| Ankle joint | Anterior | Dorsiflexion | Soleus, gastrocnemius |

From Levangie PK, Norkin CC: Joint structures and function—a comprehensive analysis, Philadelphia, 2005, FA Davis, p. 493.

Figure 15-33 illustrates normal posture and some of the abnormal deviations seen when viewing the patient from the side. Table 15-10 shows some of the malalignment postures and their effect.2,27–29

TABLE 15-10

Malalignments Viewed Laterally2,27–29

Posterior View

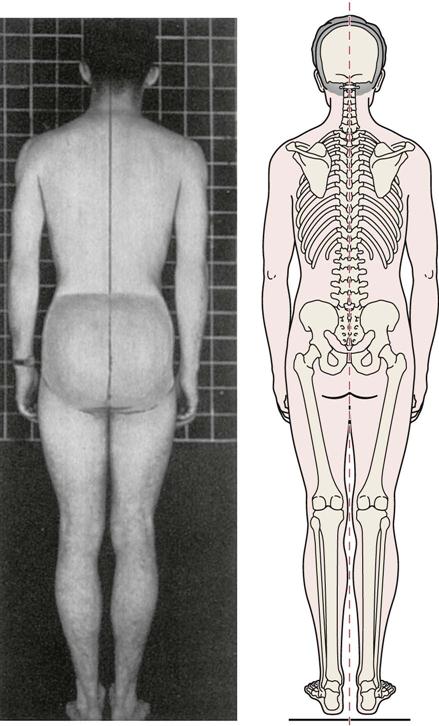

When viewing from behind (Table 15-11; see Figure 15-1, C), the examiner should note whether the following conditions hold true:

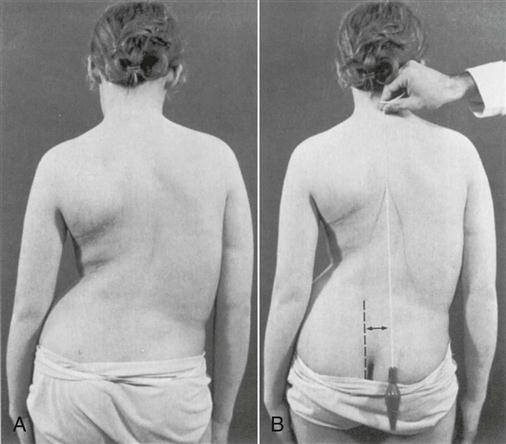

2. The spines and inferior angles of the scapulae are level (Figure 15-34), and the medial borders of the scapulae are equidistant from the spine. If not, is there a rotational or winging deformity of one of the scapulae? Defects, such as Sprengel’s deformity, should be noted (Figure 15-35).

3. The spine is straight or curved laterally, indicating scoliosis. A plumb line may be dropped from the spinous process of the seventh cervical vertebra (Figure 15-36).30 Normally, the line passes through the gluteal cleft. This line is the posterior line of reference used to divide the body into right and left halves posteriorly (see Figure 15-1, C). The distance from the vertical string to the gluteal cleft can be measured. This distance is sometimes used as a measurement of spinal imbalance, and it is noted whether the deviation is to the left or right. If a torticollis or cervicothoracic scoliosis is present, the plumb line should be dropped from the occipital protuberance.11

4. The ribs protrude or are symmetrical on both sides.

5. The waist angles are level.

6. The arms are equidistant from the body and equally rotated.

7. The PSISs are level (Figure 15-37). If one is higher than the other, one leg may be shorter or rotation of the pelvis may be present. The examiner should note how the PSISs relate to the ASISs. If the ASIS on one side and the PSIS on the other side are higher, there is a torsion deformity (anterior or posterior) at the sacroiliac joint. If the ASIS and PSIS on one side are higher than the ASIS and PSIS on the other side, there may be an up-slip at the sacroiliac joint on the high side.

9. The knee joints are level. If they are not, it may indicate that one leg is shorter than the other (Figure 15-38).

11. The heels are straight or are angled in (rear-foot varus) or out (rear-foot valgus).

Note the small, high scapula on the right. (From Tachdjian MO: Pediatric orthopedics, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders, p. 82.)

A, A typical right thoracic curve is shown. The left shoulder is lower, and the right scapula more prominent. Note the decreased distance between the right arm and the thorax with the shift of the thorax to the right. The left iliac crest appears higher, but this is caused by the shift of the thorax with fullness on the right and elimination of the waistline. The high hip is thus only apparent, not real. B, Plumb line dropped from the prominent vertebra of C7 (vertebra prominens) measures the decompensation of the upper thorax over the pelvis. The distance from the vertical plumb line to the gluteal cleft is measured in centimeters and is recorded, noting the direction of fall from the occipital protuberance (inion). (From Moe JH, Bradford DS, Winter RB, et al: Scoliosis and other spinal deformities, Philadelphia, 1978, WB Saunders, p. 14.)

TABLE 15-11

Alignment in the Standing Posture: Posterior View

| Body Segment | Line of Gravity Location | Observation |

| Head | Passes through middle of head | Head should be straight with no lateral tilting; angles between shoulders and neck should be equal |

| Arms | Arms should hang naturally so that the palms of the hands are facing the sides of the body | |

| Shoulders/spine | Passes along vertebral column in a straight line, which should bisect the back into two symmetrical halves | Scapulae should lie flat against the rib cage, be equidistant from the line of gravity and be separated by about 4 inches in the adult |

| Hips/pelvis | Passes through gluteal cleft of buttocks and should be equidistant from PSISs | The PSISs should be level; the gluteal folds should be level and symmetrical |

| Knees | Passes between knees equidistant from medial joint aspects | Look to see that the knees are level |

| Ankles/feet | Passes between ankles equidistant from the medial malleoli | The heel cords should be vertical and the malleoli should be level and symmetrical |

PSIS, Posterior superior iliac spine.

From Levangie PK, Norkin CC: Joint structures and function—a comprehensive analysis, Philadelphia, 2005, FA Davis, p. 499.

Figure 15-39 illustrates the normal posture and some of the abnormal deviations seen when viewing from behind. Table 15-12 highlights some of the malalignment postures and their effect.2,13,27,28

TABLE 15-12

Malalignments Viewed Posteriorly*2,13,27,28

*Many of the posterior malalignments are also seen anteriorly.

When viewing posture, the examiner should remember that the pelvis is usually the key to proper back posture. The normal pelvic angle is 30°, and the pelvis is held or balanced in this position by muscles. For the pelvis to “sit properly” on the femur, the following muscles must be strong, supple (mobile), and balanced: abdominals, hip flexors, hip extensors, superficial and deep back extensors, hip rotators, and hip abductors and adductors.

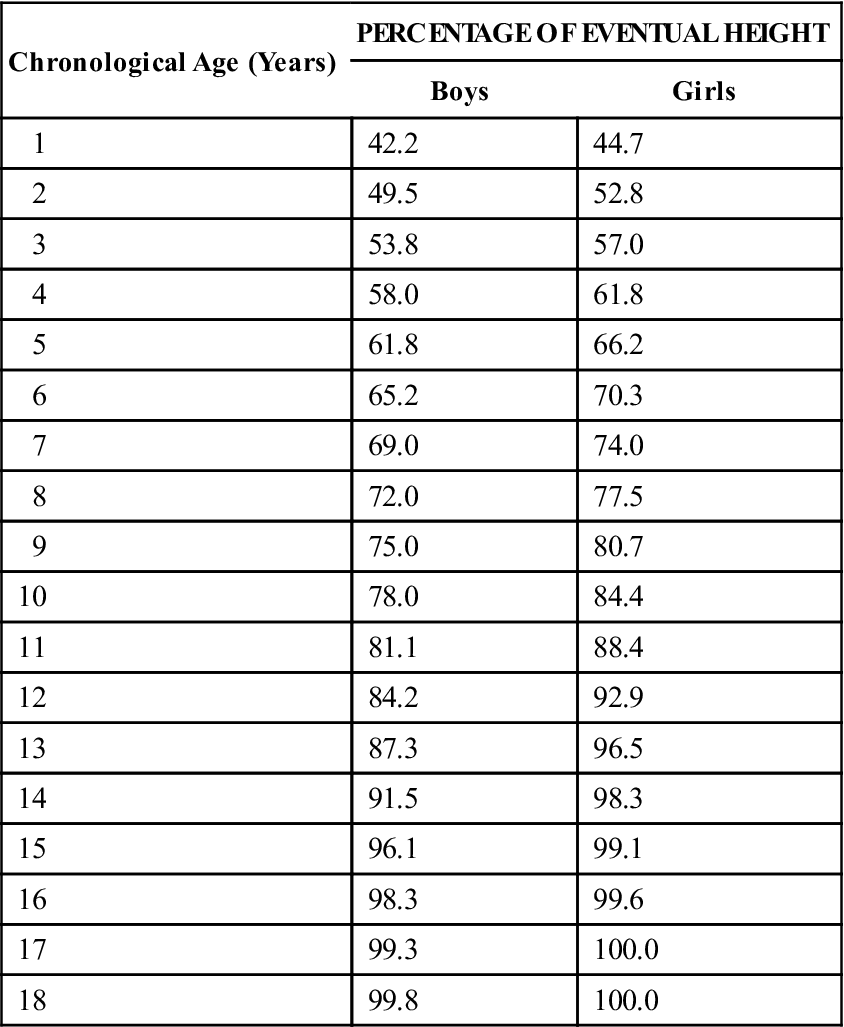

If the height of the patient is measured, especially in a child, the focal height of the child may be estimated by the use of a chart, such as the one shown in Table 15-13.31

TABLE 15-13

Percentage of Mature Height Attained at Different Ages

| Chronological Age (Years) | PERCENTAGE OF EVENTUAL HEIGHT | |

| Boys | Girls | |

| 1 | 42.2 | 44.7 |

| 2 | 49.5 | 52.8 |

| 3 | 53.8 | 57.0 |

| 4 | 58.0 | 61.8 |

| 5 | 61.8 | 66.2 |

| 6 | 65.2 | 70.3 |

| 7 | 69.0 | 74.0 |

| 8 | 72.0 | 77.5 |

| 9 | 75.0 | 80.7 |

| 10 | 78.0 | 84.4 |

| 11 | 81.1 | 88.4 |

| 12 | 84.2 | 92.9 |

| 13 | 87.3 | 96.5 |

| 14 | 91.5 | 98.3 |

| 15 | 96.1 | 99.1 |

| 16 | 98.3 | 99.6 |

| 17 | 99.3 | 100.0 |

| 18 | 99.8 | 100.0 |

From Bayley N: The accurate prediction of growth and adult height. Mod Probl Pediatr 7:234–255, 1954.

After the standing posture has been assessed, the examiner may decide to assess some additional postures (e.g., positional, sustained, or repetitive), especially if the patient has stated in the history that these different positions have caused problems or symptoms.

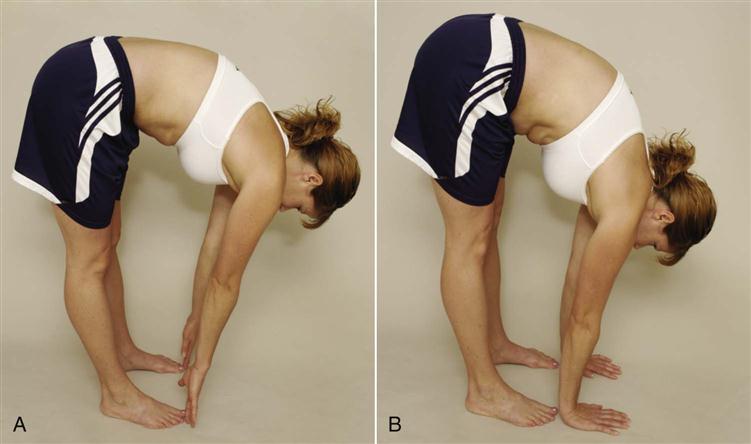

Forward Flexion

Having completed the assessment of normal standing, the examiner asks the patient to flex forward at the hips with the fingertips of both hands together so that the arms drop vertically (Figure 15-40). The feet should be together, and both knees should be straight. Any alteration from this posture will cause the spine to rotate, giving a false view.

A, Normal range of motion. Note reversal of lumbar curve. B, Excessive range of motion caused by excessive hip mobility.

From this position, using the anterior and posterior skyline views, the examiner can note the following:

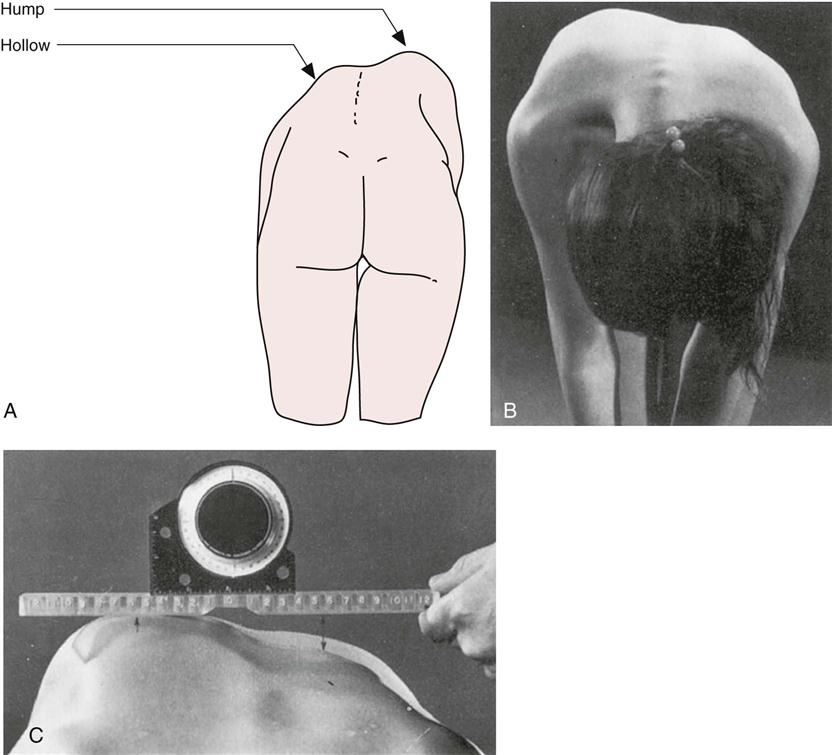

1. Whether there is any asymmetry of the rib cage (e.g., rib hump); if a hump is present, a level and tape measure may be used to obtain the perpendicular distance between the hump and hollow (Figure 15-41)11

2. Whether there is any asymmetry in the spinal musculature

3. Whether a pathological kyphosis is present

4. Whether lumbar spine straightens or flexes as it normally should

5. Whether there is any restriction to forward bending, such as spondylolisthesis or tight hamstrings (Figures 15-42 and 15-43)

A, Posterior view. B, Anterior view. The two sides are compared. Note the presence of a right thoracic prominence. C, Measurement of the prominence. The spirit level is positioned with the zero mark over the palpable spinous process in the area of maximal prominence. The level is made horizontal, and the distance to the apex of the deformity (5 to 6 cm) noted. The perpendicular distance from the level to the hollow is measured at the same distance from the midline. A 2.4-cm right thoracic prominence is shown. (From Moe JH, Bradford DS, Winter RB, et al: Scoliosis and other spinal deformities, Philadelphia, 1978, WB Saunders, p. 17.)

A, Normal thoracic roundness is demonstrated with a gentle curve to the whole spine. B, An area of increased bending is seen in the thoracic spine, indicating structural changes, in a patient with Scheuermann disease. (From Moe JH, Bradford DS, Winter RB, et al: Scoliosis and other spinal deformities, Philadelphia, 1978, WB Saunders, p. 18.)

If, in the history, the patient said that sustained forward flexion caused symptoms, the examiner should ask the patient to assume the symptom-causing posture and maintain it for 15 to 30 seconds to determine whether symptoms arise or increase. Flexion has been found to decrease the stress on the facet joints, but it can increase the pressure in the nucleus pulposus.32,33 Likewise, if repetitive forward flexion or combined movements (e.g., extension and rotation) have caused symptoms, the patient should be asked to do the repetitive or combined movements. Loading the spine by lifting an object may also cause symptoms and may be investigated if symptoms are not too great.

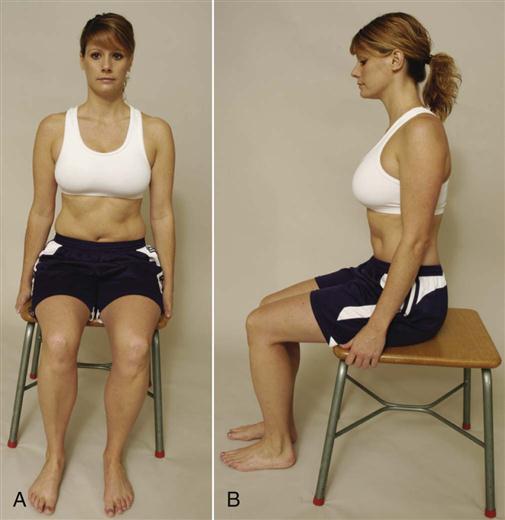

Sitting

With the patient seated on a stool so that the feet are on the ground and the back is unsupported, the examiner looks at the patient’s posture (Figure 15-44). Sitting without a back support causes the patient to support his or her own posture and increases the amount of muscle activity needed to maintain the posture.32 This observation is carried out, as in the standing position, from the front, back, and side. If any anteroposterior or lateral deviations of the spine are observed, the examiner should recall whether they were present when the patient was examined while standing. It should be noted whether the spinal curves increase or decrease when the patient is in the sitting position and how the curves change with different sitting postures.34 From the front, it can be noted whether the knees are the same distance from the floor. If they are not, this may indicate a shortened tibia. From the side, it can be noted whether one knee protrudes farther than the other. If it does, this may indicate a shortened femur on the other side.

If the patient has stated in the history that going from standing to sitting or sitting to standing resulted in symptoms, the patient should be asked to repeat these maneuvers, provided the movements do not exacerbate the symptoms too much.

Supine Lying

With the patient in the supine-lying position, the examiner notes the position of the head and cervical spine as well as the shoulder girdle. The chest area is observed for any protrusion (e.g., pectus carinatum) or sunken areas (e.g., pectus excavatum).

The abdominal musculature should be observed to see whether it is strong or flabby, and the waist angles should be noted to see whether they are equal. As in the standing position, the ASISs should be viewed to see if they are level. Any extension in the lumbar spine should be noted. In addition, it should be noted whether bending the knees helps to decrease the lumbar curve; if it does, it may indicate tight hip flexors. The lower limbs should descend parallel from the pelvis. If they do not, or if they cannot be aligned parallel and at right angles to a line joining the ASISs, it may indicate an abduction or adduction contracture at the hip.

If, in the history, the patient has complained of symptoms on arising from supine lying or from going into the supine position, the examiner should ask the patient to repeat these movements, provided they do not exacerbate the symptoms.

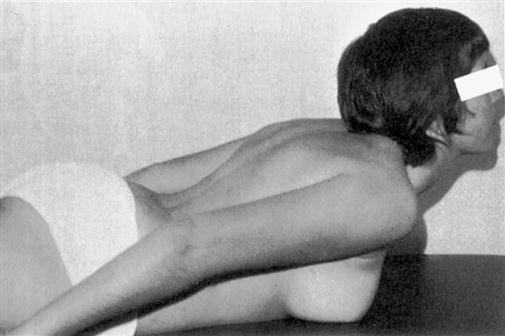

Prone Lying

With the patient lying prone, the examiner notes the position of the head, neck, and shoulder girdle, as previously described. The head should be positioned so that it is not rotated, side flexed, or extended. Any condition, such as Sprengel’s deformity or rib hump, should be noted, as should any spinal deviations. The examiner should determine whether the PSISs are level and should ensure that the musculature of the buttocks, posterior thighs, and calves is normal (Figure 15-45).

As with supine lying, if assuming the position or recovering from the position causes symptoms, the patient should be asked to repeat these movements, as long as symptoms are not made worse.

Examination

Assessment of posture primarily involves history and observation. If, on completing the history and observation, the examiner believes that a direct examination is necessary, the procedures outlined in this text for the various areas of the body should be followed. In addition, there are postural alignment measures, such as the Flexicurve ruler and other measures that may be used to record postural alignments and changes.35 With every postural assessment, however, the examiner should perform two tests: the leg length measurement36–39 and the slump test.

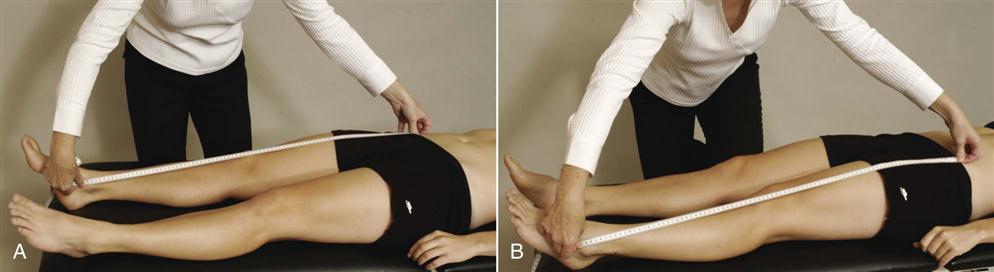

Leg Length Measurement.

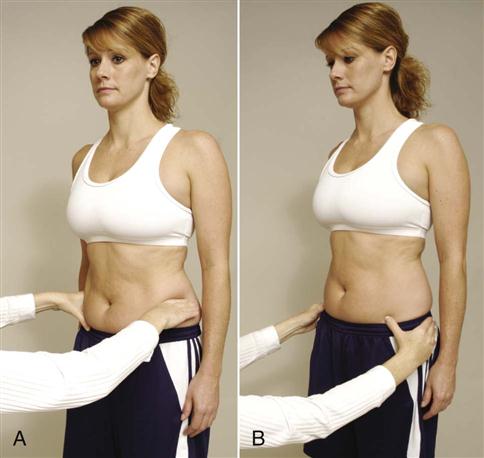

The patient lies supine with the pelvis set square or “balanced” on the legs (i.e., the legs at an angle of 90° to a line joining the ASISs). The legs should be 15 to 20 cm (6 to 8 inches) apart and parallel to each other (Figure 15-46). The examiner then places one end of the tape measure against the distal aspect of the ASIS, holding it firmly against the bone. The index finger of the other hand is placed immediately distal to the medial or lateral malleolus and pushed against it. The thumbnail is brought down against the tip of the index fingers so that the tape measure is pinched between them. A reading is taken where the thumb and finger pinch together. A slight difference, up to 1.0 to 1.5 cm (0.4 to 0.6 inch), is considered normal but can still be relevant if pathology is present. Further information on measurement of true leg length may be found in Chapter 11.

Slump Test.

The patient is seated on the edge of the examining table with the legs supported, the hips in neutral position (i.e., no rotation or abduction-adduction), and the hands behind the back (see Figure 9-62). The examination is performed in several steps. First, the patient is asked to “slump” the back into thoracic and lumbar flexion. The examiner maintains the patient’s chin in the neutral position to prevent neck and head flexion. The examiner then uses one arm to apply overpressure across the shoulders to maintain flexion of the thoracic and lumbar spines. While this position is held, the patient is asked to actively flex the cervical spine and head as far as possible (i.e., chin to chest). The examiner then applies overpressure to maintain flexion of all three parts of the spine (cervical, thoracic, lumbar), using the hand of the same arm to maintain overpressure in the cervical spine. With the other hand, the examiner then holds the patient’s foot in maximum dorsiflexion. While the examiner holds these positions, the patient is asked to actively straighten the knee as much as possible. The test is repeated with the other leg and then with both legs at the same time. If the patient is unable to fully extend the knee because of pain, the examiner releases the overpressure to the cervical spine and the patient actively extends the neck. If the knee extends farther, the symptoms decrease with neck extension, or the positioning of the patient increases the patient’s symptoms, then the test is considered positive for increased tension in the neuromeningeal tract.40–42 Further information on the slump test may be found in Chapter 9.

Additional Tests.

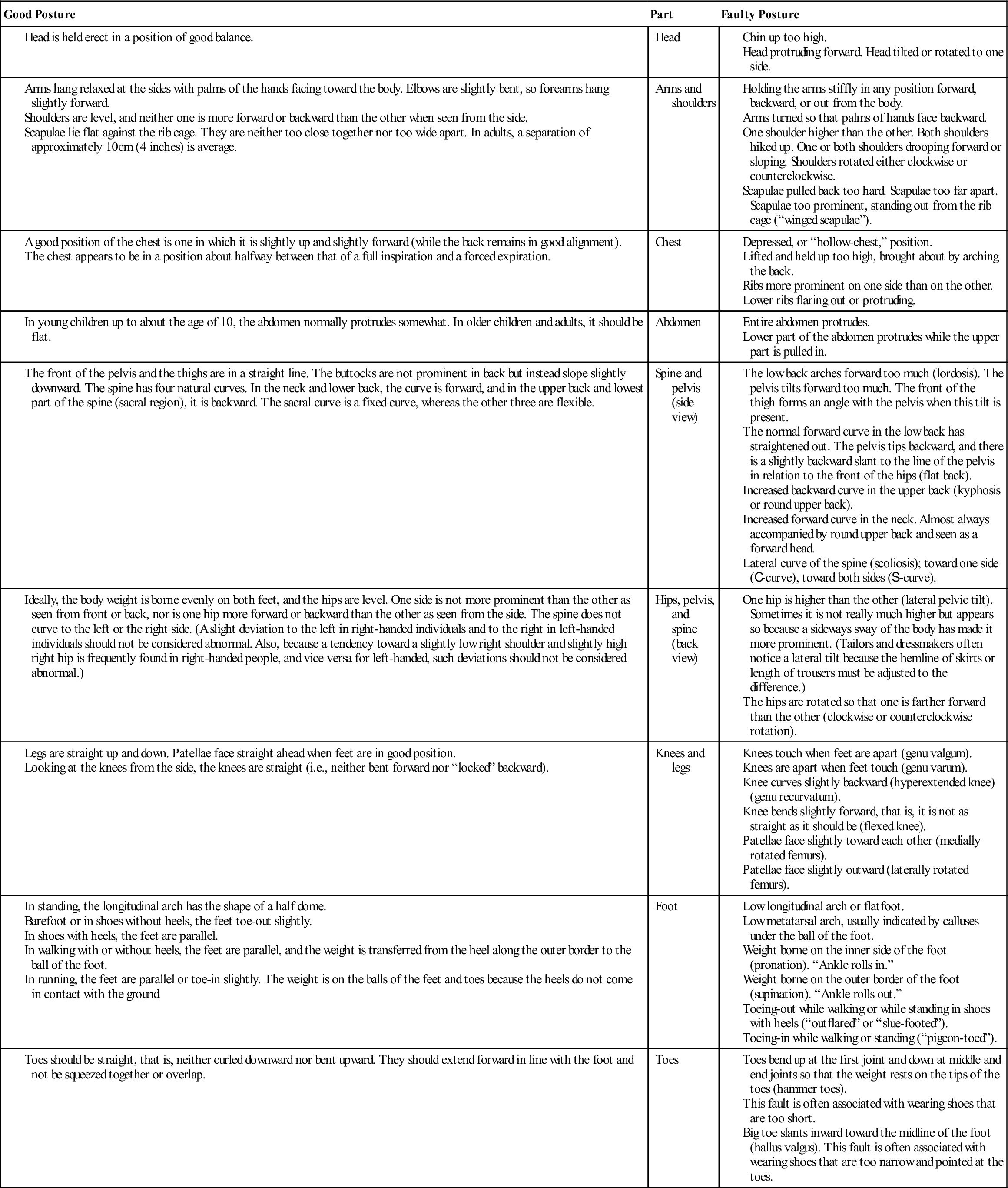

Other tests may also be performed based on what the examiner has observed. For example, if the hip flexors appear tight, the Thomas test should be performed (see Chapter 11). Refer to Table 15-14 for a detailed presentation of good and faulty posture.

TABLE 15-14

Good and Faulty Posture: Summary Chart

Modified from Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins.