Temporomandibular Joint

The temporomandibular joints are two of the most frequently used joints in the body, but they probably receive the least amount of attention. Without these joints, we would be severely hindered when talking, eating, yawning, kissing, or sucking. In any examination of the head and neck, the temporomandibular joints should be included. Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) consist of several complex multifactorial ailments involving many interrelating factors including psychosocial issues.1–3 Three cardinal features of TMD are orofacial pain, restricted jaw motion, and joint noise.1 Much of the work in this chapter has been developed from the teachings of Rocabado.4

Applied Anatomy

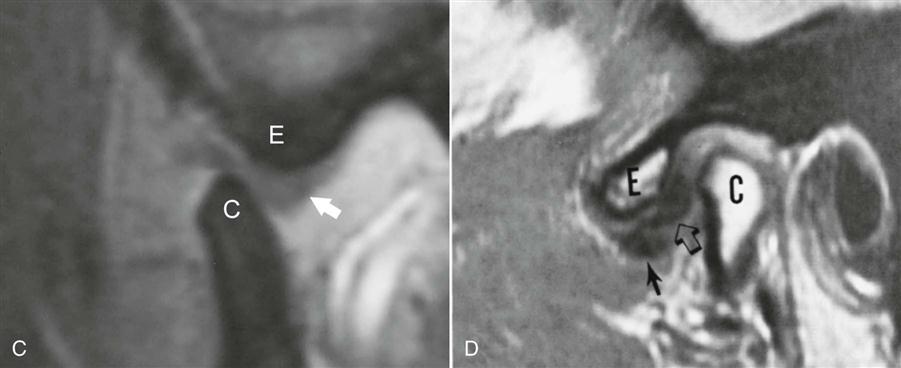

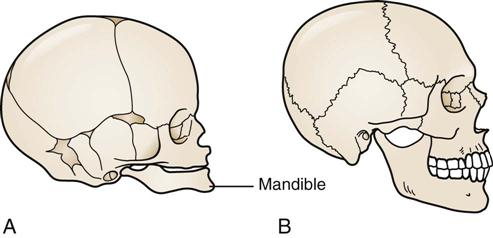

The temporomandibular joint is a synovial, condylar, modified ovoid, and hinge-type joint with fibrocartilaginous surfaces rather than hyaline cartilage5 and an articular disc; this disc completely divides each joint into two cavities (Figure 4-1). Both joints, one on each side of the jaw, must be considered together in any examination. Along with the teeth, these joints are considered to be a “trijoint complex.”

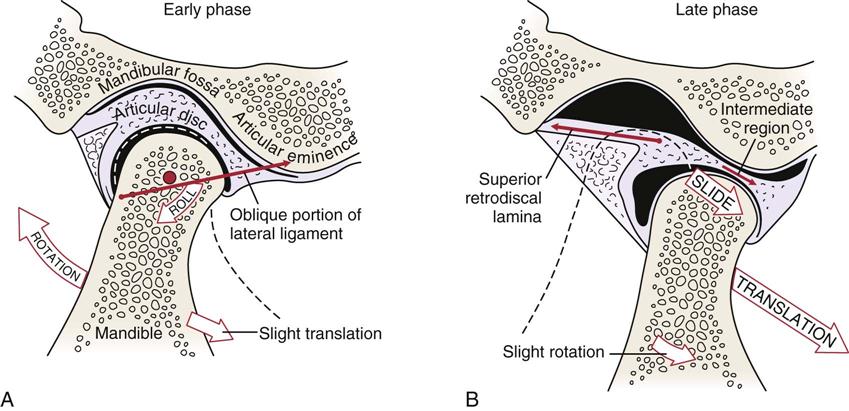

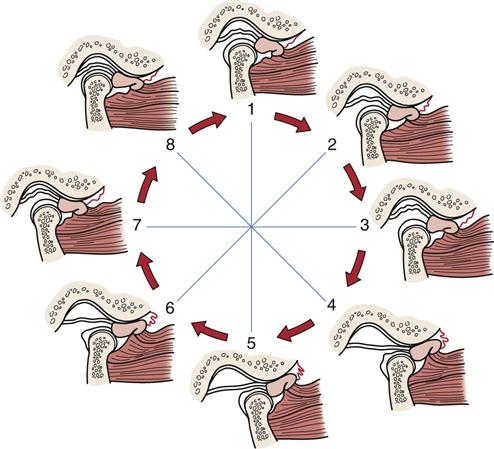

Gliding, translation, or sliding movement occurs in the upper cavity of the temporomandibular joint, whereas rotation or hinge movement occurs in the lower cavity (Figure 4-2). Rotation occurs from the beginning to the midrange of movement. The upper head of the lateral pterygoid muscle draws the disc, or meniscus, anteriorly and prepares for condylar rotation during movement. The rotation occurs through the two condylar heads between the articular disc and the condyle. In addition, the disc provides congruent contours and lubrication for the joint. Gliding, which occurs as a second movement, is a translatory movement of the condyle and disc along the slope of the articular eminence. Both gliding and rotation are essential for full opening and closing of the mouth (Figure 4-3). The capsule of the temporomandibular joints is thin and loose. In the resting position, the mouth is slightly open, the lips are together, and the teeth are not in contact but slightly apart. In the close-packed position, the teeth are tightly clenched, and the heads of the condyles are in the posterior aspect of the joint. Centric occlusion is the relation of the jaw and teeth when there is maximum contact of the teeth, and it is the position assumed by the jaw in swallowing. The position in which the teeth are fully interdigitated is called the median occlusal position.6

A, Early phase. B, Late phase. (Modified from Neumann DA: Kinesiology of the musculoskeletal system—foundations for physical rehabilitation, St Louis, 2002, CV Mosby, p. 360.)

Note that the disc is rotated posteriorly on the condyle as the condyle is translated out of the fossa. The closing movement is the exact opposite of the opening movement.

The temporomandibular joints actively displace only anteriorly and slightly laterally. When the mouth is opening, the condyles of the joint rest on the disc in the articular eminences, and any sudden movement, such as a yawn, may displace one or both condyles forward. As the mandible moves forward on opening, the disc moves medially and posteriorly until the collateral ligaments and lateral pterygoid stop its movement. The disc is then “seated” on the head of the mandible, and both disc and mandible move forward to full opening. If this “seating” of the disc does not occur, full range of motion at the temporomandibular joint is limited. In the first phase, mainly rotation occurs, primarily in the inferior joint space. In the second phase, in which the mandible and disc move together, mainly translation occurs in the superior joint space.7

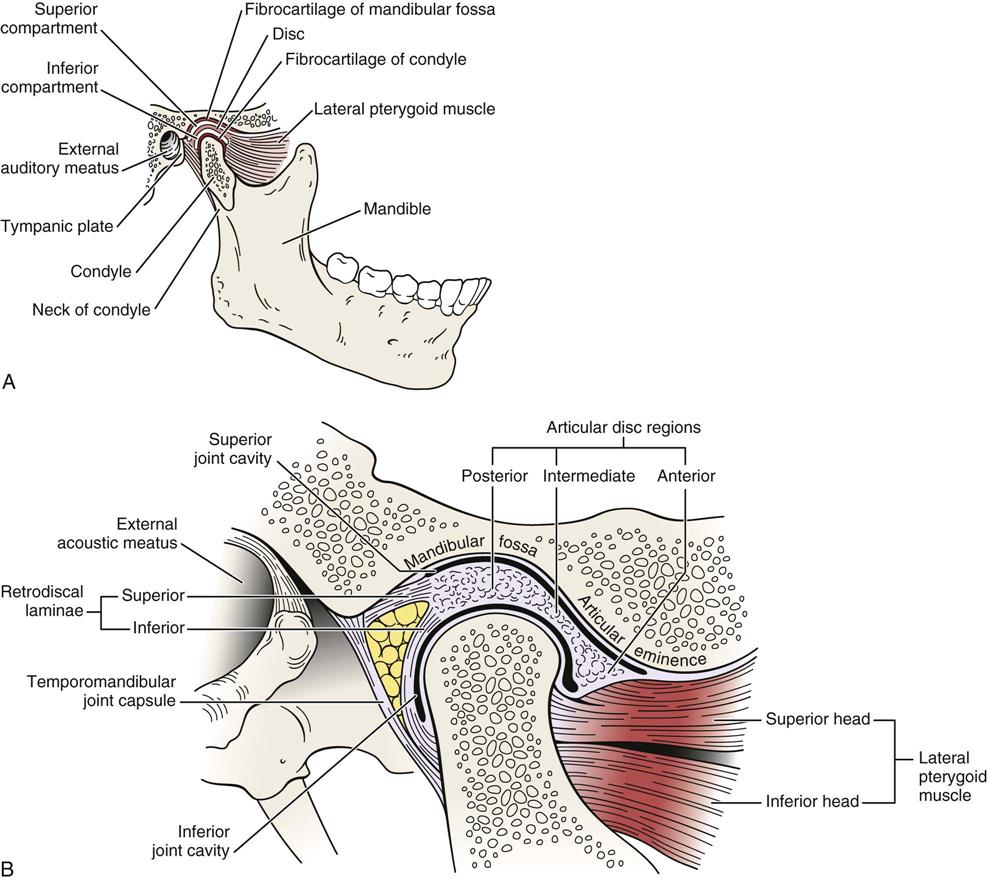

The hyoid bone, found in the anterior throat region, is sometimes referred to as the skeleton of the tongue.6 It serves as an attachment for the extrinsic tongue muscles and infrahyoid muscles and, by so doing, provides reciprocal stabilization during swallowing and through its muscle attachments can affect cervical and even shoulder function. Figure 4-4 outlines the effect of a forward head posture and the relation to the hyoid bone and related muscles.

The temporomandibular joints are innervated by branches of the auriculotemporal and masseteric branches of the mandibular nerve. The disc is innervated along its periphery but is aneural and avascular in its intermediate (force-bearing) zone.

The temporomandibular, or lateral, ligament restrains movement of the lower jaw and prevents compression of the tissues behind the condyle. In reality, this collateral ligament is a thickening in the joint capsule. The sphenomandibular and stylomandibular ligaments act as “guiding” restraints to keep the condyle, disc, and temporal bone firmly opposed. The stylomandibular ligament is a specialized band of deep cerebral fascia with thickening of the parotid fascia.

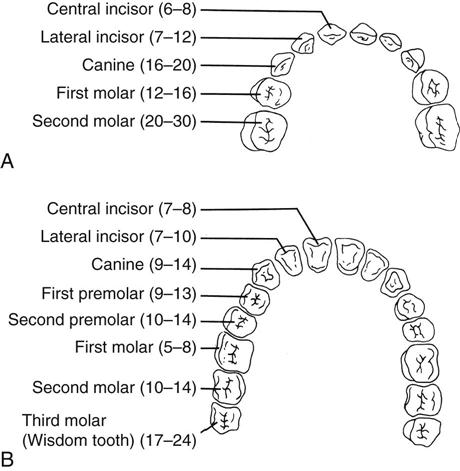

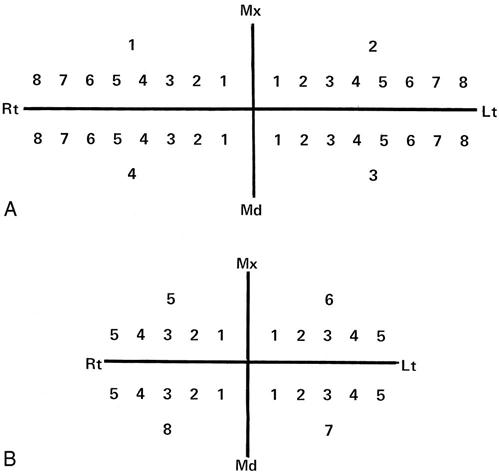

In the human, there are 20 deciduous, or temporary (“baby”), teeth and 32 permanent teeth (Figure 4-5). The temporary teeth are shed between the ages of 6 and 13 years. In the adult, the incisors are the front teeth (four maxillary and four mandibular) with the maxillary incisors being larger than the mandibular incisors. The incisors are designed to cut food. The canine teeth (two maxillary and two mandibular) are the longest permanent teeth and are designed to cut and tear food. The premolars crush and break down the food for digestion; usually they have two cusps. There are eight premolars in all, two on each side, top and bottom. The final set of teeth is the molars, which crush and grind food for digestion. They have four or five cusps, and there are two or three on each side, top and bottom (total eight to twelve). The third molars are called wisdom teeth. Missing teeth, abnormal tooth eruption, malocclusion, or dental caries (decay) may lead to problems of the temporomandibular joint. By convention, the teeth are divided into four quadrants—the upper left, the upper right, the lower left, and the lower right quadrants (Figure 4-6).

Patient History

In addition to the questions listed under Patient History in Chapter 1, the examiner should obtain the following information from the patient:8,9

1. Is there pain or restriction on opening or closing of the mouth? Pain in the fully opened position (e.g., pain associated with opening to bite an apple, yawning) is probably caused by an extra-articular problem, whereas pain associated with biting firm objects (e.g., nuts, raw fruit and vegetables) is probably caused by an intra-articular problem.10 Limited opening may be due to the disc displaced anteriorly, inert tissue tightness, or muscle spasm. Restriction can lead to anxiety in patients because of its effect on everyday activities (e.g., eating, talking).3

2. Is there pain on eating? Does the patient chew on the right? Left? Both sides equally? Loss of molars or worn dentures can lead to loss of vertical dimension, which can make chewing painful. Vertical dimension is the distance between any two arbitrary points on the face, one of these points being above and the other below the mouth, usually in midline. Often, chewing on one side is the result of malocclusion.10

3. What movements of the jaw cause pain? Do the symptoms change over a 24-hour period? The examiner should watch the patient’s jaw movement while the patient is talking. A history of stiffness on waking with pain on function that disappears as the day goes on suggests osteoarthritis.11

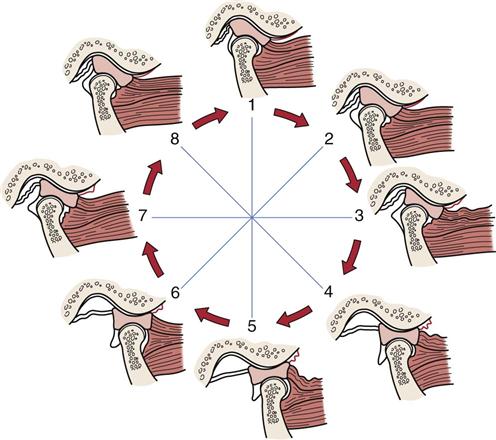

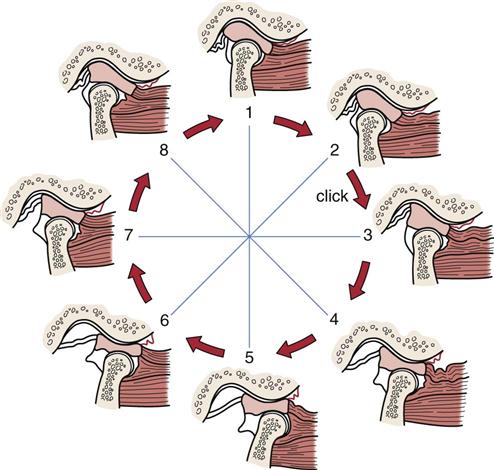

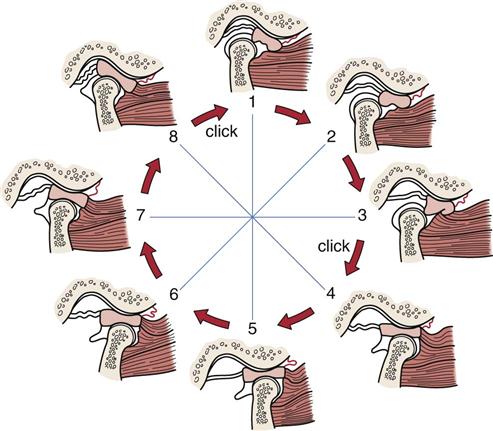

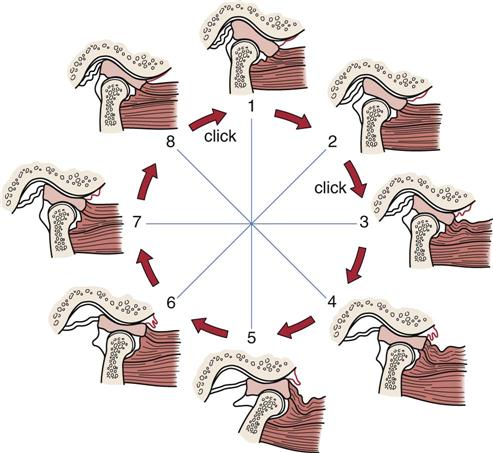

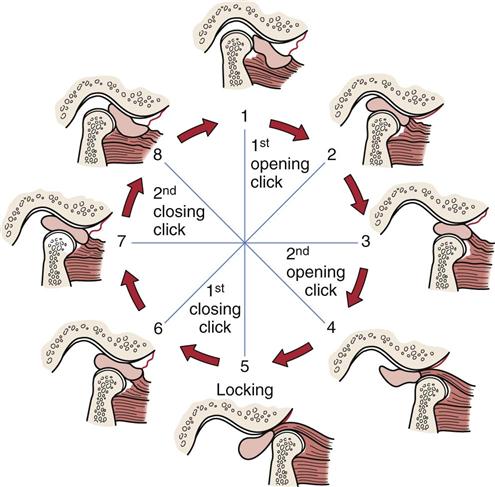

6. Has the patient complained of any crepitus or clicking? Normally, the condyles of the temporomandibular joint slide out of the concavity and onto the rim of the disc. Clicking is the result of abnormal motion of the disc and mandible. Early clicking implies a developing dysfunction, whereas late clicking is more likely to mean a chronic problem. Clicking may occur when the condyle slides back off the rim into the center (Figure 4-7).12 If the disc sticks or is bunched slightly, opening causes the condyle to move abruptly over the disc and into its normal position, resulting in a single click (see Figure 4-7).13 There may be a partial anterior displacement (subluxation) or dislocation of the disc, which the condyle must override to reach its normal position when the mouth is fully open (Figure 4-8). This override may also cause a click. Similarly, a click may occur if the disc is displaced anteriorly and/or medially, causing the condyle to override the posterior rim of the disc later than normal during mouth opening. This is referred to as disc displacement with reduction. If clicking occurs in both directions, it is called reciprocal clicking (Figure 4-9). The opening click occurs somewhere during the opening or protrusive path, and the click indicates the condyle is slipping over the thicker posterior border of the disc to its position in the thinner middle or intermediate zone. The closing (reciprocal) click occurs near the end of the closing or retrusive path as the pull of the superior lateral pterygoid muscle causes the disc to slip more anteriorly and the condyle to move over its posterior border.

Clicks may also be caused by adhesions (Figure 4-10), especially in people who clench their teeth (bruxism). These “adhesive” clicks occur in isolation, after the period of clenching.14 If adhesions occur in the superior or inferior joint space, translation or rotation will be limited. This presents as a temporary closed lock, which then opens with a click.

If the articular eminence is abnormally developed (i.e., short, steep posterior slope or long, flat anterior slope), the maximum anterior movement of the disc may be reached before maximum translation of the condyle has occurred. As the condyle overrides the disc, a loud crack is heard, and the condyle-disc leaps or jogs (subluxes) forward.14

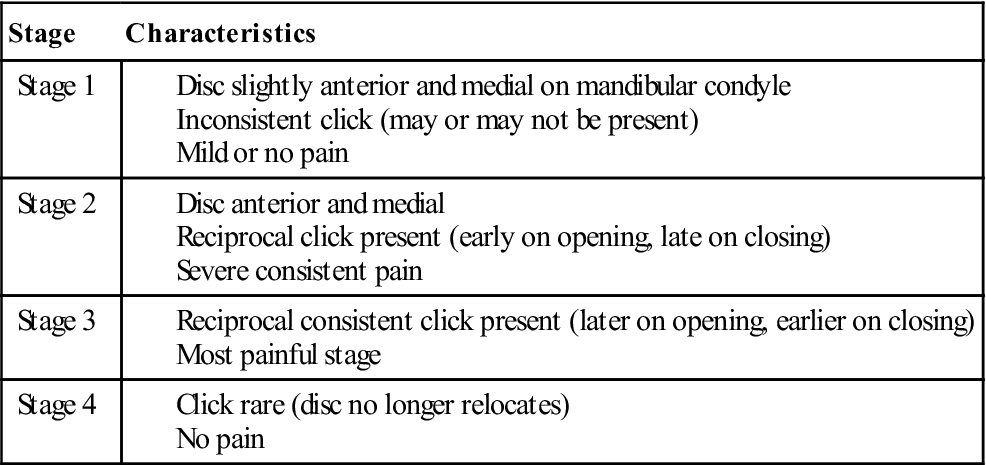

“Soft” or “popping” clicks that are sometimes heard in normal joints are caused by ligament movement, articular surface separation, or sucking of loose tissue behind the condyle as it moves forward. These clicks usually result from muscle incoordination. “Hard” or “cracking” clicks are more likely to indicate joint pathology or joint surface defects. Soft crepitus (like rubbing knuckles together) is a sound that sometimes occurs in symptomless joints and is not necessarily an indication of pathology.15 Hard crepitus (like a footstep on gravel) is indicative of arthritic changes in the joints. The clicking may be caused by uncoordinated muscle action of the lateral pterygoid muscles, a tear or perforation in the disc, osteoarthrosis, or occlusal imbalance. Normally, the upper head of the lateral pterygoid muscle pulls the disc forward. If the disc does not move first, the condyle clicks over the disc as it is pulled forward by the lower head of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler7 have divided disc displacement into four stages (Table 4-1).

7. Has the mouth or jaw ever locked? Locking may imply that the mouth does not fully open or it does not fully close and is often related to problems of the disc or joint degeneration. Locking is usually preceded by reciprocal clicking. If the jaw has locked in the closed position, the locking is probably caused by a disc with the condyle being posterior or anteromedial to the disc. Even if translation is blocked (e.g., “locked” disc), the mandible can still open 30 mm by rotation. If there is functional dislocation of the disc with reduction (see Figure 4-8), the disc is usually positioned anteromedially, and opening is limited. The patient complains that the jaw “catches” sometimes, so the locking occurs only occasionally and, at those times, opening is limited. If there is functional anterior dislocation of the disc without reduction, a closed lock occurs. Closed lock implies there has been anterior and/or medial displacement of the disc so that the disc does not return to its normal position during the entire movement of the condyle. In this case, opening is limited to about 25 mm, the mandible deviates to the affected side (Figure 4-11), and lateral movement to the uninvolved side is reduced.14 If locking occurs in the open position, it is probably caused by subluxation of the joint or possibly by posterior disc displacement (see Figure 4-11). With an open lock, there are two clicks on opening, when the condyle moves over the posterior rim of the disc and then when it moves over the anterior rim of the disc, and two clicks on closing. If, after the second click occurs on opening, the disc lies posterior to the condyle, it may not allow the condyle to slide back (Figure 4-12).16 If the condyle dislocates outside the fossa, it is a true dislocation with open lock; the patient cannot close the mouth, and the dislocation must be reduced.16

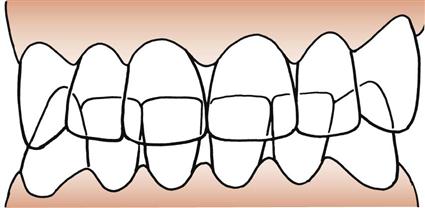

9. Does the patient grind the teeth or hold them tightly? Bruxism is the forced clenching and grinding of the teeth, especially during sleep. This may lead to facial, jaw, or tooth pain, or headaches in the morning along with muscle hypertrophy. If the front teeth are in contact and the back ones are not, facial and temporomandibular pain may develop as a result of malocclusion. Normally, the upper teeth cover the upper one third of the bottom teeth (Figure 4-13).

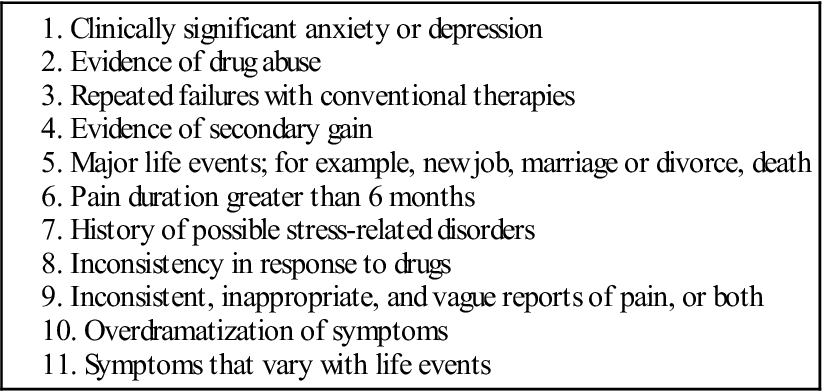

10. Does there appear to be any related psychosocial problems? Temporomandibular dysfunction is often accompanied by related psychosocial issues.1,17 Table 4-2 outlines psychosocial factors that may affect the temporomandibular joint.

11. Are any teeth missing? If so, which ones, and how many? The presence or absence of teeth and their relation to one another must be noted on a table similar to the one shown in Figure 4-6. Their presence or absence can have an effect on the temporomandibular joints and their muscles. If some teeth are missing, others may deviate to fill in the space, altering the occlusion.

13. Does the patient have any difficulty swallowing? Does the patient swallow normally or gulp? What happens to the tongue when the patient swallows? Does it move normally, anteriorly, or laterally? Is there any evidence of tongue thrust or thumb sucking? For example, the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) and the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), which control facial expression and mastication and contribute to speech, also control anterior lip seal. If lip seal is weakened, the teeth may move anteriorly, an action that would be accentuated in “tongue thrusters.” The normal resting position of the tongue is against the anterior palate (Figure 4-14). It is the position in which one would place the tongue to make a “clicking” sound.

16. Has the patient noticed any voice changes? Changes may be caused by muscle spasm.

18. Does the patient ever feel dizzy or faint?

19. Has the patient ever worn a dental splint? If so, when? For how long?

Between positions 2 and 3, a click is felt as the condyle moves across the posterior border into the intermediate zone of the disc. Normal condyle-disc function occurs during the remaining opening and closing movement. In the closed joint position (1), the disc is again displaced forward (and medially) by activity of the superior lateral pterygoid muscle.

During opening, the condyle passes over the posterior border of the disc into the intermediate area of the disc, thus reducing the dislocated disc.

Between positions 2 and 3, a click is felt as the condyle moves across the posterior border of the disc. Normal condyle-disc function occurs during the remaining opening and closing movement until the closed joint position is approached. A second click is heard as the condyle once again moves from the intermediate zone to the posterior border of the disc between positions 8 and 1.

TABLE 4-1

Temporomandibular Disc Dysfunction

Data from Iglarsh ZA, Snyder-Mackler L: Tempormandibular joint and the cervical spine. In Richardson JK, Iglarsh ZA (editors): Clinical orthopedic physical therapy, Philadelphia, 1994, WB Saunders.

The condyle never assumes a normal relation to the disc but instead causes the disc to move forward ahead of it. This condition limits the distance the condyle can translate forward.

1, The disc always stays in anterior position with the jaw closed. 1-4, Disc is displaced posterior to the condyle with one or two opening clicks. 5-6, The disc disturbs jaw closing after maximum opening. 6-1, The disc is again displaced to anterior position from the posterior with one or two clicks.

TABLE 4-2

Checklist of Psychological and Behavioral Factors*

*Note: The first two factors are the most significant and warrant further evaluation by a mental health professional; factors 3 to 6 need at least one more factor for consideration of referral; and factors 7 to 11 require three or more factors for consideration of referral to a mental health professional.

From McNeill C, Mohl ND, Rugh JD, et al: Temporomandibular disorders: diagnosis, management, education and research. J Am Dent Assoc 120:259, 1990.

Observation

When assessing the temporomandibular joints, the examiner must also assess the posture of the cervical spine and head. For example, it is necessary that the head be “balanced” on the cervical spine and be in proper postural alignment.

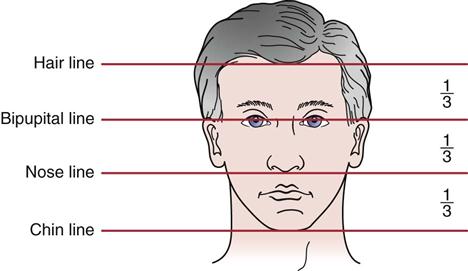

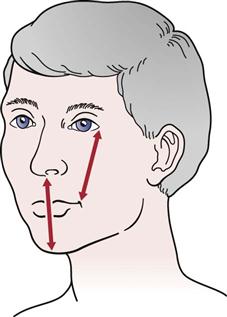

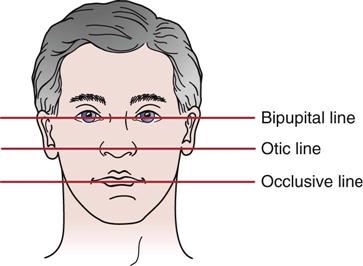

1. Is the face symmetrical horizontally and vertically, and are facial proportions normal (Figure 4-15)? The examiner should check the eyebrows, eyes, nose, ears, and corners of the mouth for symmetry on both horizontal and vertical planes. Horizontally, the face of an adult is divided into thirds (Figure 4-16); this demonstrates normal vertical dimension. Usually the upper and lower teeth are used to measure vertical dimension. The horizontal bipupital, otic, and occlusive lines should be parallel to each other (Figure 4-17). Loss of teeth on one side can lead to convergence in which at least two of the lines may converge because the jaw line is short on one side relative to the other. A quick way to measure the vertical dimension is to measure from the lateral edge of the eye to the corner of the mouth and from the nose to the chin (Figure 4-18). Normally, the two measurements are equal. If the second measurement is smaller than the first by 1 mm or more, there has been a loss of vertical dimension, which may have resulted from loss of teeth, overbite, or temporomandibular joint dysfunction. In children, elderly persons, and those with massive tooth loss, the lower third of the face is not well developed (lack of teeth) or has recessed (Figure 4-19). As the teeth grow, the lower third develops into its normal proportion. The examiner should notice whether there is any paralysis, which could be indicated by ptosis (drooping of an eyelid) or by drooping of the mouth on one side (Bell palsy).

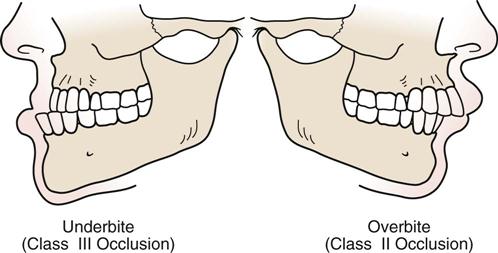

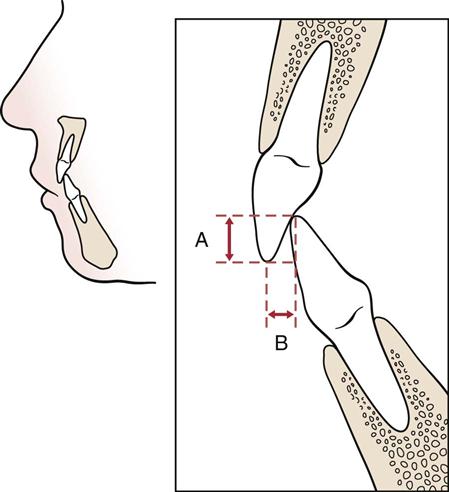

2. The examiner should note whether the teeth are normally aligned or there is any crossbite, underbite, or overbite (Figure 4-20). With crossbite, the teeth of the mandible are lateral to the upper (maxillary) teeth on one side and medial on the opposite side. There is abnormal interdigitation of the teeth. With anterior crossbite, the lower incisors are ahead of the upper incisors. With posterior crossbite, there is a transverse abnormal relation of the teeth. In underbite, the mandibular teeth are unilaterally, bilaterally, or in pairs in buccoversion (i.e., they lie anterior to the maxillary teeth). In overbite, the anterior maxillary incisors extend below the anterior mandibular incisors when the jaw is in centric occlusion. A small amount of overbite (2 to 3 mm) anteriorly is the most common position of the teeth. This is because the maxillary arch is slightly longer than the mandibular arch. Overjet (Figure 4-21) is the distance that the maxillary incisors close over the mandibular incisors when the mouth is closed. This distance is normally 2 to 3 mm. Occlusal interference refers to premature teeth contact, which tends to deflect the jaw laterally and/or anteriorly.18 Any orthodontic appliances or false teeth present should also be evaluated for fit and possible sore spots.

3. The examiner should note whether there is any malocclusion that may result in a faulty bite. Malocclusion may be a major factor in the development of disc problems of the temporomandibular joints. Occlusion occurs when the teeth are in contact and the mouth is closed. Malocclusion is defined as any deviation from normal occlusion. Class I occlusion refers to the normal anteroposterior relation of the maxillary teeth to mandibular teeth. A slight modification with only the incisors affected and overjet slightly larger is sometimes classified as a Class I malocclusion. Class II malocclusion (overbite) occurs when the mandibular teeth are positioned posterior to their normal position relative to the maxillary teeth. This malocclusion deformity involves all the teeth, including the molars. The designation Class II Division 1 malocclusion (also called large overjet or horizontal overlap) indicates that the maxillary incisors demonstrate significant overjet. Class II Division 2 malocclusion (also called deep overbite or vertical overlap) implies that overjet is not significant but that there is overbite and lateral flaring of the lateral maxillary incisors.19 Class III malocclusion (i.e., underbite) occurs when the mandibular teeth are positioned anterior to their normal position relative to the maxillary teeth. If maxillary and mandibular teeth are on the same vertical plane, a Class III malocclusion would be present.

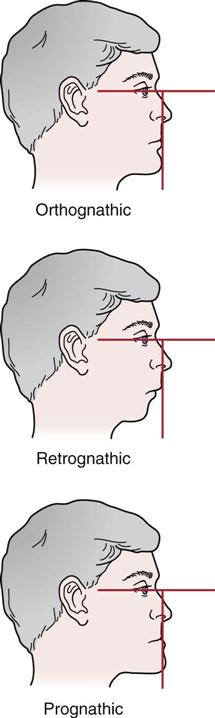

4. What is the facial profile? The orthognathic profile is the normal, “straight-jawed” form. With this facial profile, a vertical line dropped perpendicular to the bipupital line would touch the upper and lower lips and the tip of the chin. In a person with a retrognathic profile, the chin would lie behind the vertical line and the person would be said to have a “receding chin.” With the prognathic profile, the chin would be in front of the vertical line and the person would have a protruded or “strong” chin (Figure 4-22).19

5. The examiner should note whether the patient demonstrates normal bony and soft-tissue contours. When the patient bites down, do the masseter muscles bulge as they normally should? Hypertrophy caused by overuse may lead to abnormal wear of the teeth. When looking at the soft tissues, it is important to note symmetry. The upper lip should normally cover two thirds of the maxillary teeth at rest. If it does not, the lip is said to be short.7 If the lip can be drawn over the upper teeth, however, the upper lip is said to be functional, and no treatment is necessary. The lower lip normally covers the mandibular teeth and, when the mouth is closed, part of the maxillary teeth.

6. Is the patient able to move the tongue properly? Can the patient move the tongue up to and against the palate? Can the tongue be protruded or rolled? Is the patient able to “click” the tongue? Tongue thrusting refers to forward movement of the tongue, usually to push against the lower teeth; it also occurs when the tongue is pushed against the upper teeth and the lower teeth are closed firmly against it, creating an oral seal.20 Tongue thrusters find it easier to thrust the tongue if the head is protruded. Therefore, to test for tongue thrusting, the patient’s head posture is corrected and the patient is asked to swallow. In the tongue thruster, swallowing causes the tongue to move forward resulting in protrusion of the head. Tongue thrusting may be due to hyperactivity of the masticatory muscles. When one swallows, the hyoid bone should move up and down quickly. If it moves only upward and slowly, and the suboccipital muscles posteriorly contract, it is suggestive of a tongue thrust.21

Look for asymmetry both vertically and horizontally. Asymmetrical changes may be seen with no smile (A) or with smile (B). These asymmetrical differences may or may not be related to pathology.

Normally, the distance from the lateral edge of the eye to the corner of the mouth equals the distance from nose to point of chin.

A, Vertical overlap (overbite). B, Horizontal overlap (overjet). (Redrawn from Friedman MH, Weisberg J: The temporomandibular joint. In Gould JA, editor: Orthopedics and sports physical therapy, St Louis, 1990, CV Mosby, p. 578.)

Examination

The examiner must remember that many problems of the temporomandibular joints may be the result of or related to problems in the cervical spine or teeth. Therefore, the cervical spine is at least partially included in any temporomandibular assessment.

Active Movements

With the patient in the sitting position, the examiner watches the active movements, noting whether they deviate from what would be considered normal range of motion and whether the patient is willing to do the movement. The patient is first asked to carry out active movements of the cervical spine. The most painful movements, if any, should be done last.

During flexion of the neck, the mandible moves up and forward, and the posterior structures of the neck become tight. During extension, the mandible moves down and back, and the anterior structures of the neck become tight. The examiner should note whether the patient can flex and extend the neck while keeping the mouth closed or whether the patient must open the mouth to do these movements. The patient should be asked to place a fist under the chin and then open the mouth while keeping the fist in place and the lower jaw against it. If the mouth opens in this way, movement of the neck into extension is occurring because the head is rotating backwards on the temporomandibular condyles. This test movement would be especially important if the patient subjectively feels that there is a loss of neck extension. With side flexion of the neck to the right, maximum occlusion occurs on the right. Side flexion and rotation of the neck occur to the same side, and so if these movements are carried out to the right, maximum occlusion also occurs to the right.

Having observed the neck movements, the examiner goes on to note the active movements of the temporomandibular joints. The movements of the mandible can be measured with a millimeter ruler, depth gauge, or vernier calipers. When using the ruler, the examiner should pick a midline point from which to measure opening and lateral deviation.22 This same ruler can be used to measure protrusion and retrusion.

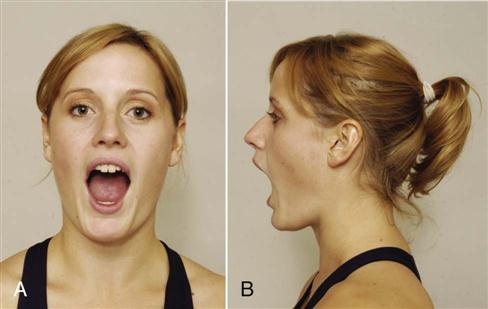

Opening and Closing of the Mouth

With opening and closing of the mouth, the normal arc of movement of the jaw is smooth and unbroken; that is, both temporomandibular joints are working in unison with no asymmetry or sideways movement, and both joints are bilaterally rotating and translating equally. Any alteration may cause or indicate potential problems in the temporomandibular joints. To observe any asymmetries, opening and closing of the mouth must be done slowly. The first phase of opening is rotation, which can be tested by having the patient open the mouth as widely as possible while maintaining the tongue against the roof (hard palate) of the mouth. Usually this movement causes minimal pain and occurs even in the presence of acute temporomandibular dysfunction. The second phase of opening is translation and rotation as the condyles move along the slope of the eminence. This phase begins when the tongue loses contact with the roof of the mouth.2 Most of the clicking sensations occur during this phase.

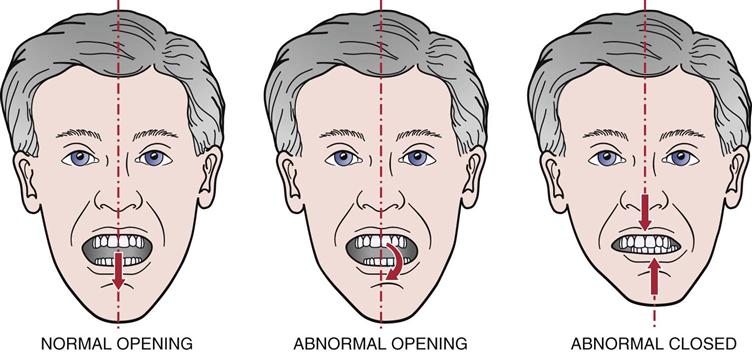

Normally, the mandible should open and close in a straight line (Figures 4-23 and 4-24), provided the bilateral action of the muscles is equal and the inert tissues have normal pliability. If deviation occurs to the left on opening (see Figure 4-23) (a C-type curve) or to the right (a reverse C-type curve), hypomobility is evident toward the side of the deviation caused either by a displaced disc without reduction or unilateral muscle hypomobility;9 if the deviation is an S-type or reverse S-type curve, the problem is probably muscular imbalance or medial displacement as the condyle “walks around” the disc on the affected side.9 The chin deviates toward the affected side, usually because of spasm of the pterygoid or masseter muscles or an obstruction in the joint. Early deviation on opening is usually caused by muscle spasm, whereas late deviation on opening is usually a result of capsulitis or a tight capsule. Pain or tenderness, especially on closing, indicates posterior capsulitis.

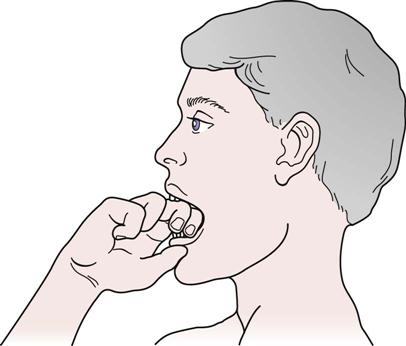

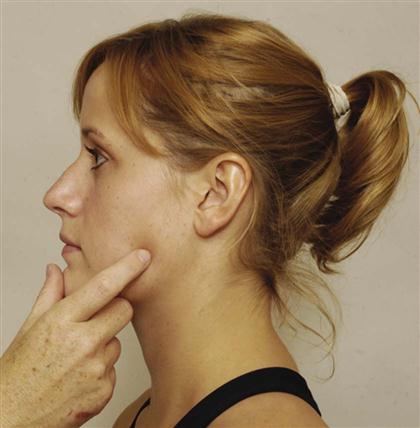

The examiner should then determine whether the patient’s mouth can functionally be opened. The functional or full active opening is determined by having the patient try to place two or three flexed proximal interphalangeal joints within the mouth opening (Figure 4-25).23 This opening should be approximately 35 to 55 mm.3 Normally, only about 25 to 35 mm of opening is needed for everyday activity. If the patient has pain on opening, the examiner should also measure the amount of opening to the point of pain and compare this distance with functional opening.8 If the space is less than this, the temporomandibular joints are said to be hypomobile. Kropmans et al.24 have pointed out that for treatment, at least 6 mm of change has to be seen to be a detectable difference when doing more than one measurement or to determine the effect of treatment.

Figure 4-25 Functional opening “knuckle” test.

Figure 4-25 Functional opening “knuckle” test.As the mouth opens, the examiner should palpate the external auditory meatus with the index or little finger (fleshy part anterior). The patient is then asked to close the mouth. When the examiner first feels the condyle touch the finger, the temporomandibular joints are in the resting position. This resting position of the temporomandibular joints is called the freeway space, or interocclusal space. The freeway space is the potential space or vertical distance that is found between the teeth when the mandible is in the resting position. To determine the freeway space, the examiner marks a point on the chin and a point vertically above on the upper lip below the nose. The patient closes the mouth into centric occlusion, and the distance between the two points is measured. Then the patient is asked to say three simple words (e.g., “boy, boy, boy”) and then maintain this position of the jaw without moving. The distance between the two points is measured again. The difference between the two measurements is the freeway space.18 Normally, the space between the front teeth at this point is 2 to 4 mm.

If rotation does not occur at the temporomandibular joint, the mouth cannot open fully. There may be gliding at the temporomandibular joint, but rotation has not occurred. If translation (gliding) does not occur, the mandible may still open up to 30 mm as a result of rotation. Normally, when the mouth opens, the disc moves forward approximately 7 mm, and the condyle moves forward approximately 14 mm.25

If clicking (see question 6 under the earlier History section) occurs on opening, the examiner should ask the patient to open the mouth with the jaw protruded and retruded. If the clicking is eliminated with protrusion and accentuated with retrusion, it is likely the problem is an anterior disc displacement with reduction.26 Anterior disc displacement without reduction cannot be determined as confidently.27

Protrusion of the Mandible

The examiner asks the patient to protrude or jut the lower jaw out past the upper teeth. The patient should be able to do this without difficulty. The normal movement is more than 7 mm, measured from the resting position to the protruded position.3 The normal values vary depending on the degree of overbite (greater movement) or underbite (less movement).

Retrusion of the Mandible

The examiner asks the patient to retrude or pull the lower jaw in or back as far as possible. In full retention or centric relation, the temporomandibular joint is in a close-packed position. The normal movement is 3 to 4 mm.10

Lateral Deviation or Excursion of the Mandible

For lateral deviation, the teeth are slightly disoccluded, and the patient moves the mandible laterally, first to one side and then to the other. With the joints in the resting position, two points are picked on the upper and lower teeth that are at the same level. When the mandible is laterally deviated, the two points, which have moved apart, are measured, giving the amount of lateral deviation. The normal lateral deviation is 10 to 15 mm.3 During lateral deviation, the opposite condyle moves forward, down, and toward the motion side. The condyle on the motion side (e.g., left condyle on left lateral deviation) remains relatively stationary and becomes more prominent.10 Any lateral deviation from the normal opening position or abnormal protrusion to one side indicates that the lateral pterygoid, masseter, or temporalis muscle, the disc, or the lateral ligament on the opposite side is affected.

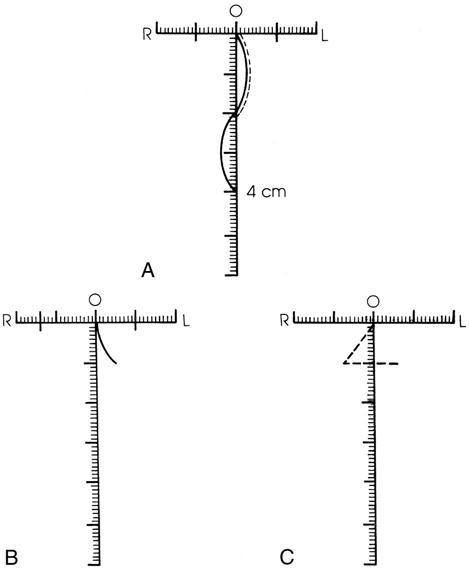

When charting any changes, the examiner should note the type of opening deviation as well as the functional opening and any lateral deviation (Figure 4-26).

A, Deviation to both right (R) and left (L) on opening; maximum opening, 4 cm; lateral deviation equal (1 cm each direction); protrusion on functional opening (dashed lines). B, Capsule-ligamentous pattern; opening limited to 1 cm; lateral deviation greater to right than left; deviation to left on opening. C, Protrusion is 1 cm; lateral deviation to right on protrusion (indicates weak lateral pterygoid on opposite side).

Mandibular Measurement

Next, the examiner should measure the mandible from the posterior aspect of the temporomandibular joint to the notch of the chin (Figure 4-27). Both sides are measured and compared for equality (the normal distance is 10 to 12 cm). Any difference indicates a developmental problem or structural change leading to left or right convergence; the patient may not be able to obtain balancing in the midline.

Swallowing and Tongue Position

The patient is asked to relax and then swallow. The patient is asked to leave the tongue in the position it assumed when swallowing occurred. The examiner, wearing rubber gloves, then separates the lips and notes the position of the tongue (e.g., between teeth? at upper anterior palate?).18

Cranial Nerve Testing

If injury to the cranial nerves is suspected, the cranial nerves should be tested.

Passive Movements

Very seldom are passive movements carried out for the temporomandibular joints except when the examiner is attempting to determine the end feel of the joints. The amount of passive opening (full passive stretch) may also be measured and compared with functional opening amount.8 The normal end feel of these joints is tissue stretch on opening and teeth contact (“bone-to-bone”) on closing. When the teeth are in maximum contact, the horizontal overjet is sometimes measured. The overjet is the horizontal distance from the edge of the upper central incisors to the lower central incisors (see Figure 4-21). If the lower teeth extend over the upper teeth, this malocclusion condition is called an underbite. Overbite is the vertical overlap of the teeth.

Resisted Isometric Movements

Resisted isometric movements of the temporomandibular joints are relatively difficult to test. The jaw should be in the resting position. The examiner applies firm but gentle resistance to the joints and asks the patient to hold the position, saying “Don’t let me move you.”

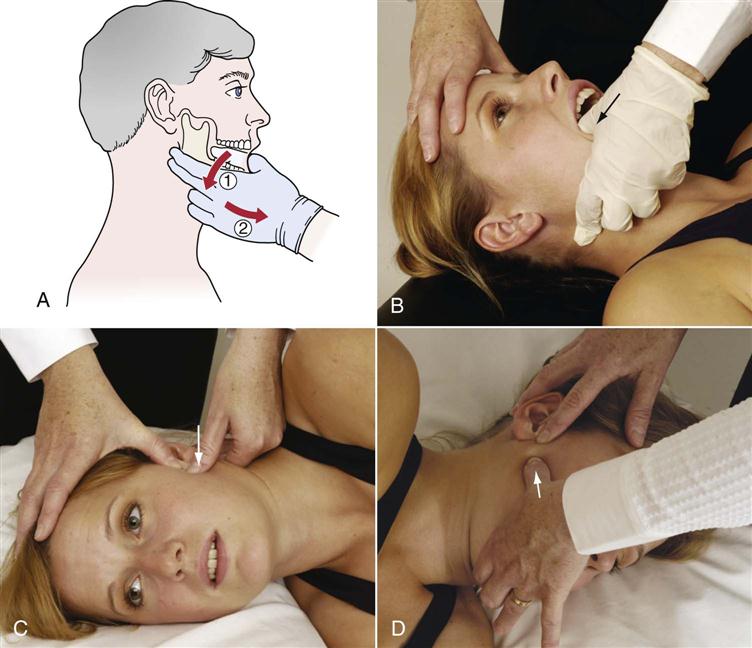

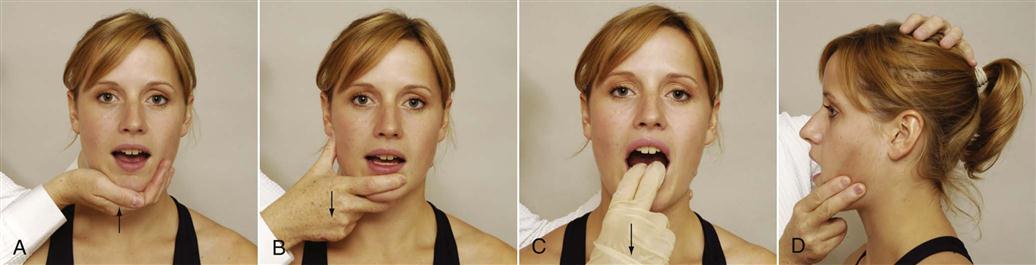

Opening of the Mouth (Depression).

This movement may be tested by applying resistance at the chin or, using a rubber glove, over the teeth with one hand while the other hand rests behind the head or neck or over the forehead to stabilize the head (Figure 4-28, A; Table 4-3).

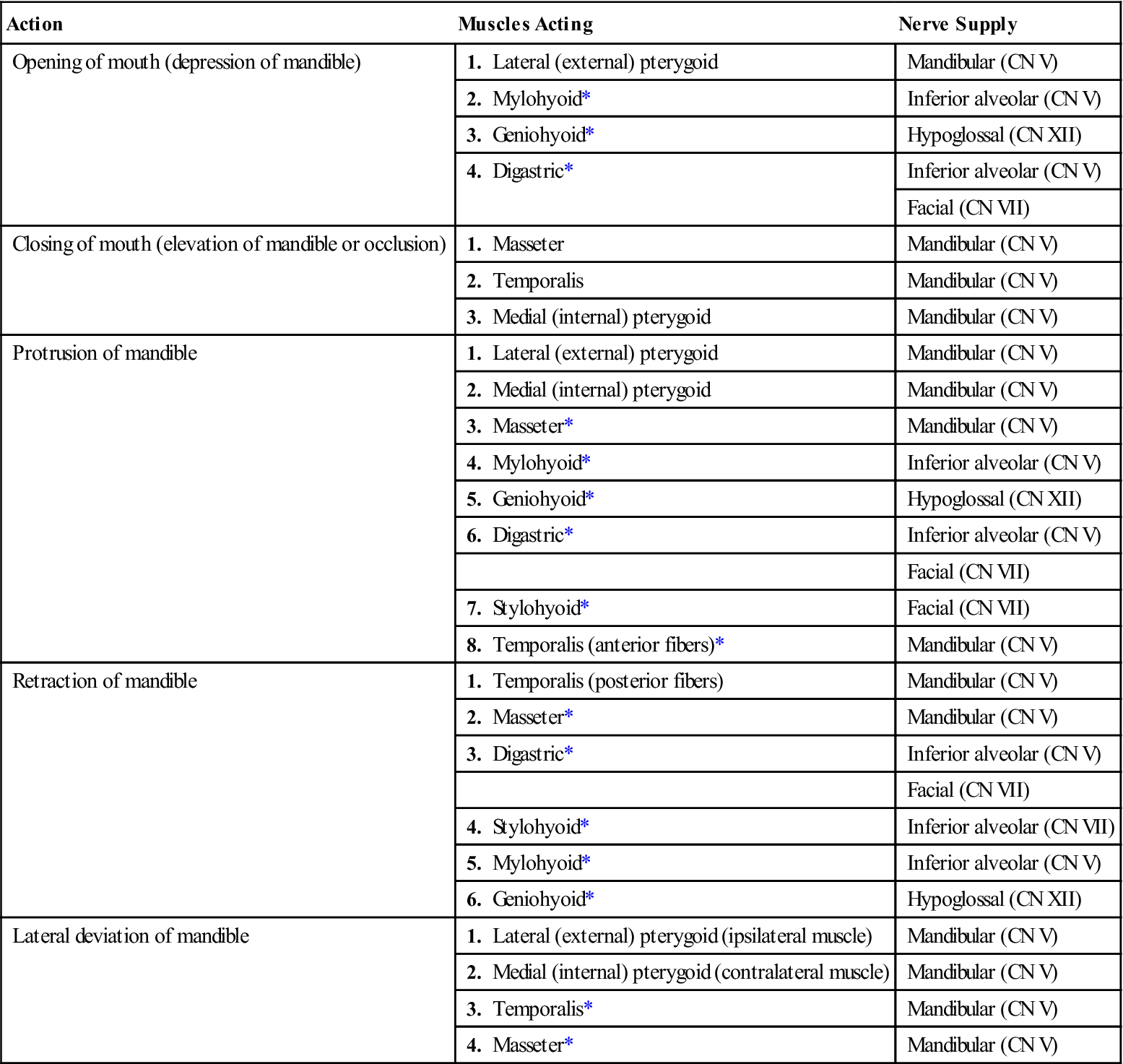

TABLE 4-3

Muscles of the Temporomandibular Joint: Their Actions and Nerve Supply

| Action | Muscles Acting | Nerve Supply |

| Opening of mouth (depression of mandible) | 1. Lateral (external) pterygoid | Mandibular (CN V) |

| 2. Mylohyoid* | Inferior alveolar (CN V) | |

| 3. Geniohyoid* | Hypoglossal (CN XII) | |

| 4. Digastric* | Inferior alveolar (CN V) | |

| Facial (CN VII) | ||

| Closing of mouth (elevation of mandible or occlusion) | 1. Masseter | Mandibular (CN V) |

| 2. Temporalis | Mandibular (CN V) | |

| 3. Medial (internal) pterygoid | Mandibular (CN V) | |

| Protrusion of mandible | 1. Lateral (external) pterygoid | Mandibular (CN V) |

| 2. Medial (internal) pterygoid | Mandibular (CN V) | |

| 3. Masseter* | Mandibular (CN V) | |

| 4. Mylohyoid* | Inferior alveolar (CN V) | |

| 5. Geniohyoid* | Hypoglossal (CN XII) | |

| 6. Digastric* | Inferior alveolar (CN V) | |

| Facial (CN VII) | ||

| 7. Stylohyoid* | Facial (CN VII) | |

| 8. Temporalis (anterior fibers)* | Mandibular (CN V) | |

| Retraction of mandible | 1. Temporalis (posterior fibers) | Mandibular (CN V) |

| 2. Masseter* | Mandibular (CN V) | |

| 3. Digastric* | Inferior alveolar (CN V) | |

| Facial (CN VII) | ||

| 4. Stylohyoid* | Inferior alveolar (CN VII) | |

| 5. Mylohyoid* | Inferior alveolar (CN V) | |

| 6. Geniohyoid* | Hypoglossal (CN XII) | |

| Lateral deviation of mandible | 1. Lateral (external) pterygoid (ipsilateral muscle) | Mandibular (CN V) |

| 2. Medial (internal) pterygoid (contralateral muscle) | Mandibular (CN V) | |

| 3. Temporalis* | Mandibular (CN V) | |

| 4. Masseter* | Mandibular (CN V) |

Closing of the Mouth (Elevation or Occlusion).

One hand is placed over the back of the head or neck to stabilize the head while the other hand is placed under the chin of the patient’s slightly open mouth to resist the movement (Figure 4-28, B). In a second method, the examiner uses a rubber glove and places two fingers over the patient’s lower teeth (mandible) to resist the movement (Figure 4-28, C).

Lateral Deviation of the Jaw.

One of the examiner’s hands is placed over the side of the head above the temporomandibular joint to stabilize the head. The other hand is placed along the jaw of the patient’s slightly open mouth, and the patient pushes out against it (Figure 4-28, D). Both sides are tested individually.

Functional Assessment

After the basic movements of the temporomandibular joints have been tested, the examiner should test functional activities or activities of daily living involving the use of the temporomandibular joints. These activities include chewing, swallowing, coughing, talking, and blowing. If the patient complains of pain while eating, the examiner can ask the patient to bite down on a tongue depressor held between the teeth in different positions to see if the compressive movement is painful in the teeth or temporomandibular joint. Biting down on one side stresses the temporomandibular joint on the opposite side.6

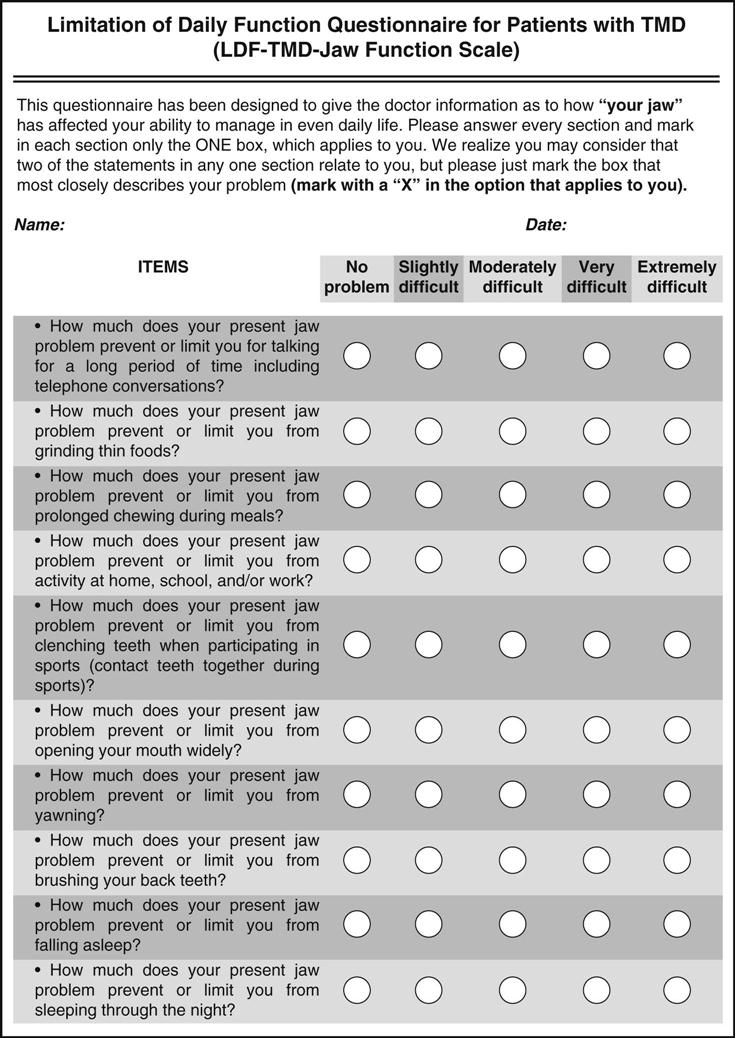

In addition, there are a number of function questionnaires that may be used as part of the functional assessment: the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD),28–33 the Limitations of Daily Function Questionnaire (TMJ)34 (Figure 4-29), the Jaw Functional Limitation Scale,35 the Mandibular Function Impairment Questionnaire (MFIQ),36,37 the History Questionnaire for Jaw Pain, and the TMJ Scale.

Special Tests

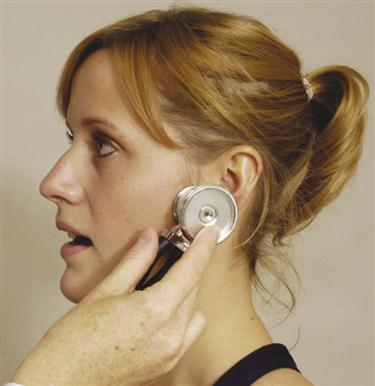

There are no routine special tests for the temporomandibular joints. The Chvostek test ![]() may be used to determine whether there is pathology involving the seventh cranial (facial) nerve (Figure 4-30). The examiner taps the parotid gland overlying the masseter muscle. If the facial muscles twitch, the test is considered positive.

may be used to determine whether there is pathology involving the seventh cranial (facial) nerve (Figure 4-30). The examiner taps the parotid gland overlying the masseter muscle. If the facial muscles twitch, the test is considered positive.

If the patient is suffering from a facial nerve injury (Bell palsy), the examiner may use the facial nerve grading system (see Table 2-24) developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology.8

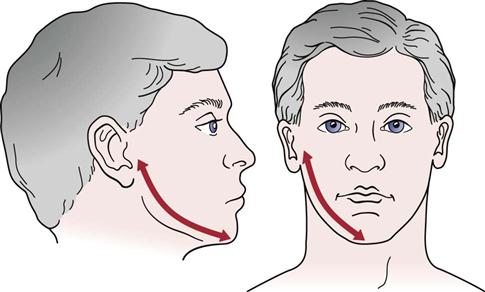

The examiner can listen to (auscultate) the temporomandibular joints during movement (Figure 4-31). The movements “listened to” include opening and closing of the mouth, lateral deviation of the mandible to the right and left, and mandibular protrusion. Normally, a sound would be heard only on occlusion. This is a single, solid sound, not a “slipping” sound. A slipping sound could occur if the teeth are not “hitting” simultaneously. The most common joint noise is reciprocal clicking (see Figure 4-9), which occurs when the mouth opens and when it closes. The clicking ![]() is clinical evidence that the condyle is slipping over the disc and then self-reducing. The opening click results when the condyle slips under the posterior aspect of the disc (reduces) or slips anterior to the disc (subluxes) on opening. The second click, which is quieter, occurs when the condyle slips posterior to the disc (subluxes) or into its proper position and reduces. A single click may occur if the condyle gets caught behind the disc on opening (see Figure 4-7) or if the condyle slips behind the disc on closing. On opening, the later the click occurs, the more anterior lies the disc. The later the opening click, the more the disc is displaced anteriorly, and the more likely it is to lock. A closing click is usually caused by loosening of the structures attaching the disc to the condyle. Clicking is more likely to occur in hypermobile joints.38,39

is clinical evidence that the condyle is slipping over the disc and then self-reducing. The opening click results when the condyle slips under the posterior aspect of the disc (reduces) or slips anterior to the disc (subluxes) on opening. The second click, which is quieter, occurs when the condyle slips posterior to the disc (subluxes) or into its proper position and reduces. A single click may occur if the condyle gets caught behind the disc on opening (see Figure 4-7) or if the condyle slips behind the disc on closing. On opening, the later the click occurs, the more anterior lies the disc. The later the opening click, the more the disc is displaced anteriorly, and the more likely it is to lock. A closing click is usually caused by loosening of the structures attaching the disc to the condyle. Clicking is more likely to occur in hypermobile joints.38,39

Grating noise (crepitus) is usually indicative of degenerative joint disease or a perforation in the disc. Painful crepitus usually means that the disc has eroded, the condyle bone and temporal bone are rubbing together, and much of the fibrocartilage has been lost. While the examiner is listening, each movement should be done four or five times to ensure a correct diagnosis.

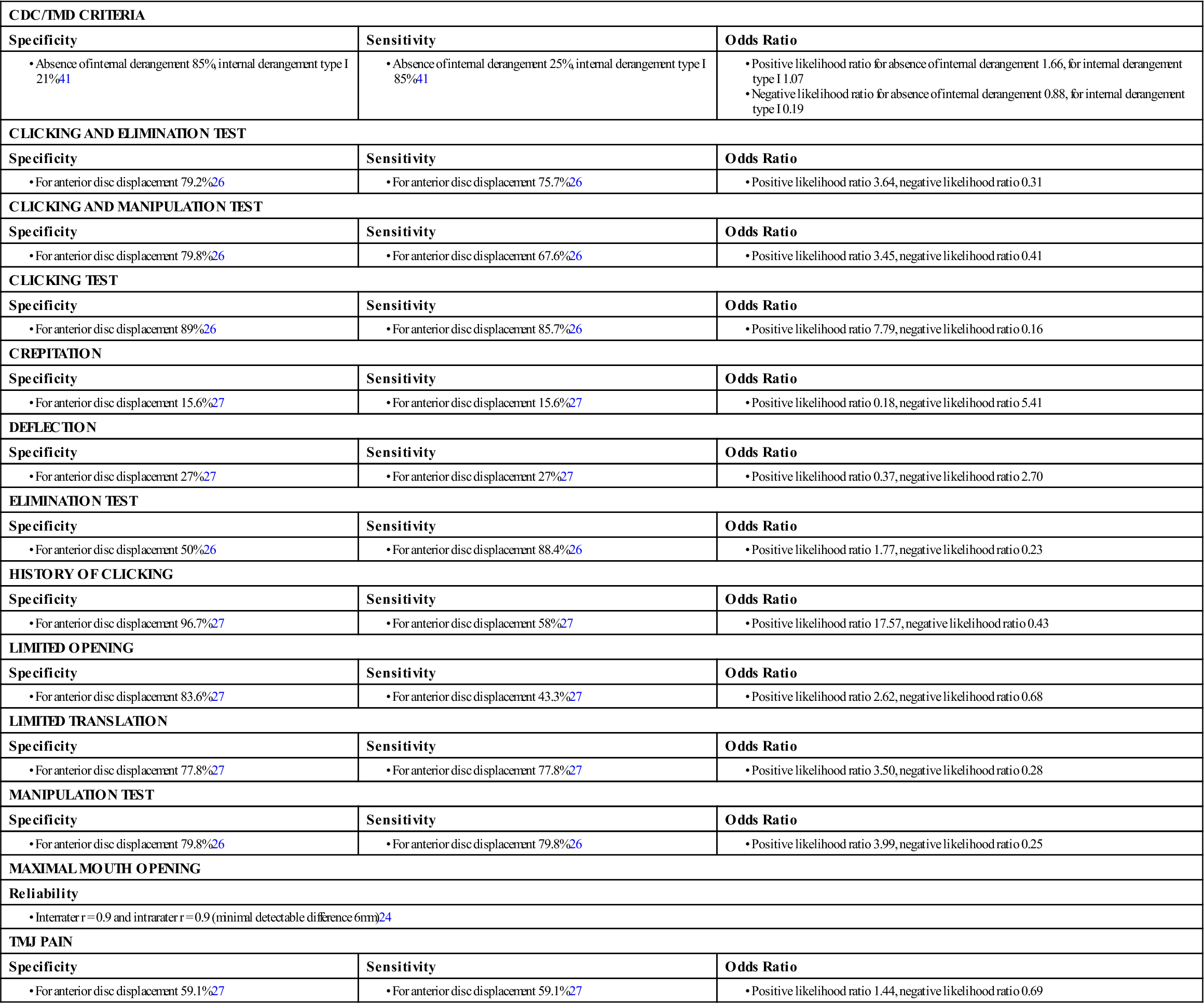

For the reader who would like to review them, the reliability, validity, specificity, sensitivity, and odds ratios of some of the special tests used in the temporomandibular joint are available in on the Evolve website.

APPENDIX 4-1

CDC, Centers for Disease Control; TMD, temporomandibular disorder.

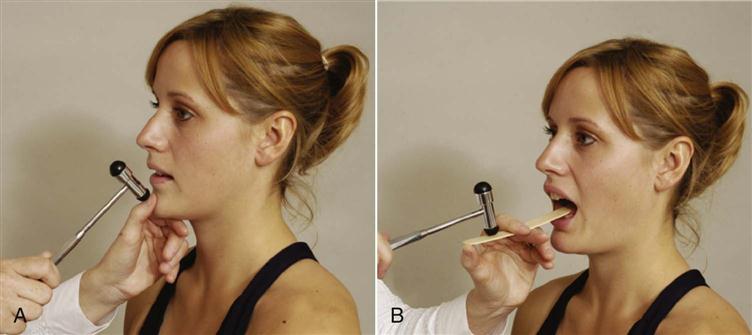

Reflexes and Cutaneous Distribution

The reflex of the temporomandibular joints is called the jaw reflex. The examiner’s thumb is placed on the chin of the patient with the patient’s mouth relaxed and open in the resting position. The patient is asked to close the eyes. If this is not done, the patient commonly tenses as he or she sees the reflex hammer being swung toward the examiner’s thumb or the tongue depressor, and the test does not work. The examiner then taps the thumbnail with a neurological hammer (Figure 4-32, A). The jaw reflex may also be tested by using a tongue depressor (Figure 4-32, B). The examiner holds the tongue depressor firmly against the bottom teeth; while the patient relaxes the jaw muscles, the examiner taps the tongue depressor with the reflex hammer. The reflex closes the mouth and is a test of cranial nerve V.

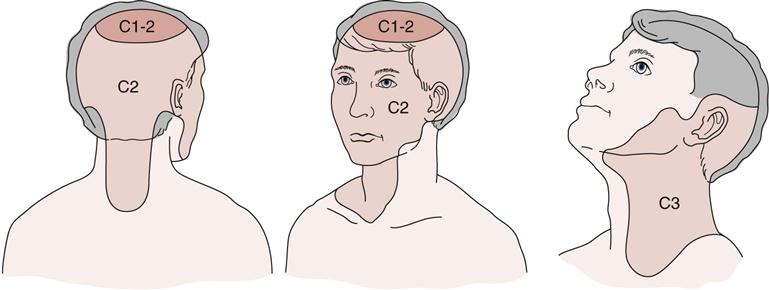

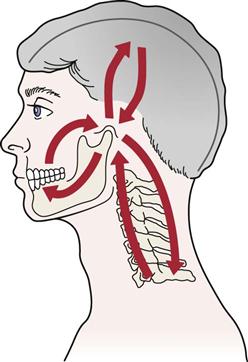

The examiner must be aware of the dermatome patterns for the head and neck (Figure 4-33) as well as the sensory nerve distribution of the peripheral nerves (see Figure 3-66). Pain may be referred from the temporomandibular joint to the teeth, neck, or head, and vice versa (Figure 4-34). Table 4-4 shows the muscles of the temporomandibular joint and their referral of pain.

TABLE 4-4

Temporomandibular Muscles and Referral of Pain

| Muscle | Referral Pattern |

| Masseter | Cheek, mandible to forehead or ear |

| Temporalis | Maxilla to forehead and side of head above ear |

| Medial pterygoid | Posterior mandible to temporomandibular joint |

| Lateral pterygoid | Cheek to temporomandibular joint |

| Digastric | Lateral cervical spine to posterolateral skull |

| Occipitofrontal | Above eye, over eyelid, and up over lateral aspect of skull |

Joint Play Movements

The joint play movements of the temporomandibular joints are then tested. Pain on performing these tests may indicate articular problems or pathology to the retrodiscal tissues.40

Longitudinal Cephalad and Anterior Glide.

Wearing rubber gloves, the examiner places the thumb on the patient’s lower teeth inside the mouth with the index finger on the mandible outside the mouth. The mandible is then distracted by pushing down with the thumb and pulling down and forward with the index finger while the other fingers push against the chin, acting as a pivot point. The examiner should feel the tissue stretch of the joint. Each joint is done individually while the other hand and arm stabilize the head (Figure 4-35, A).

A, Longitudinal cephalad and anterior glide. B, Lateral glide of the mandible. Examiner pushes mandible laterally. C, Medial glide of the mandible. Examiner pushes mandible medially while palpating temporomandibular joint with other thumb. D, Posterior glide of the mandible. Examiner pushes mandible posteriorly while palpating temporomandibular joint with other thumb.

Lateral Glide of the Mandible.

The patient lies supine with the mouth slightly open and the mandible relaxed. The examiner places the thumb inside the mouth along the medial side of the mandible and teeth. By pushing the thumb laterally, the mandible glides laterally.21 Each joint is done individually (Figure 4-35, B).

Medial Glide of the Mandible.

The patient is in side lying with the mandible relaxed. The examiner places the thumb (or overlapping thumbs) over the lateral aspect of the mandibular condyle outside the mouth and applies a medial pressure to the condyle, gliding the condyle medially.21 Each joint is done individually (Figure 4-35, C).

Posterior Glide of the Mandible.

The patient is in side lying with the mandible relaxed. The examiner places the thumb (or overlapping thumbs) over the anterior aspect of the mandibular condyle outside the mouth and applies a posterior pressure to the condyle, gliding the condyle posteriorly.21 Each joint is done individually (Figure 4-35, D).

Palpation

To palpate the temporomandibular joints, the examiner places the fingers (padded part anteriorly) in the patient’s external auditory canals and asks the patient to actively open and close the mouth. As this is being done, the examiner determines whether both sides are moving simultaneously and whether the movement is smooth. If the patient feels pain on closing, the posterior capsule is usually involved.

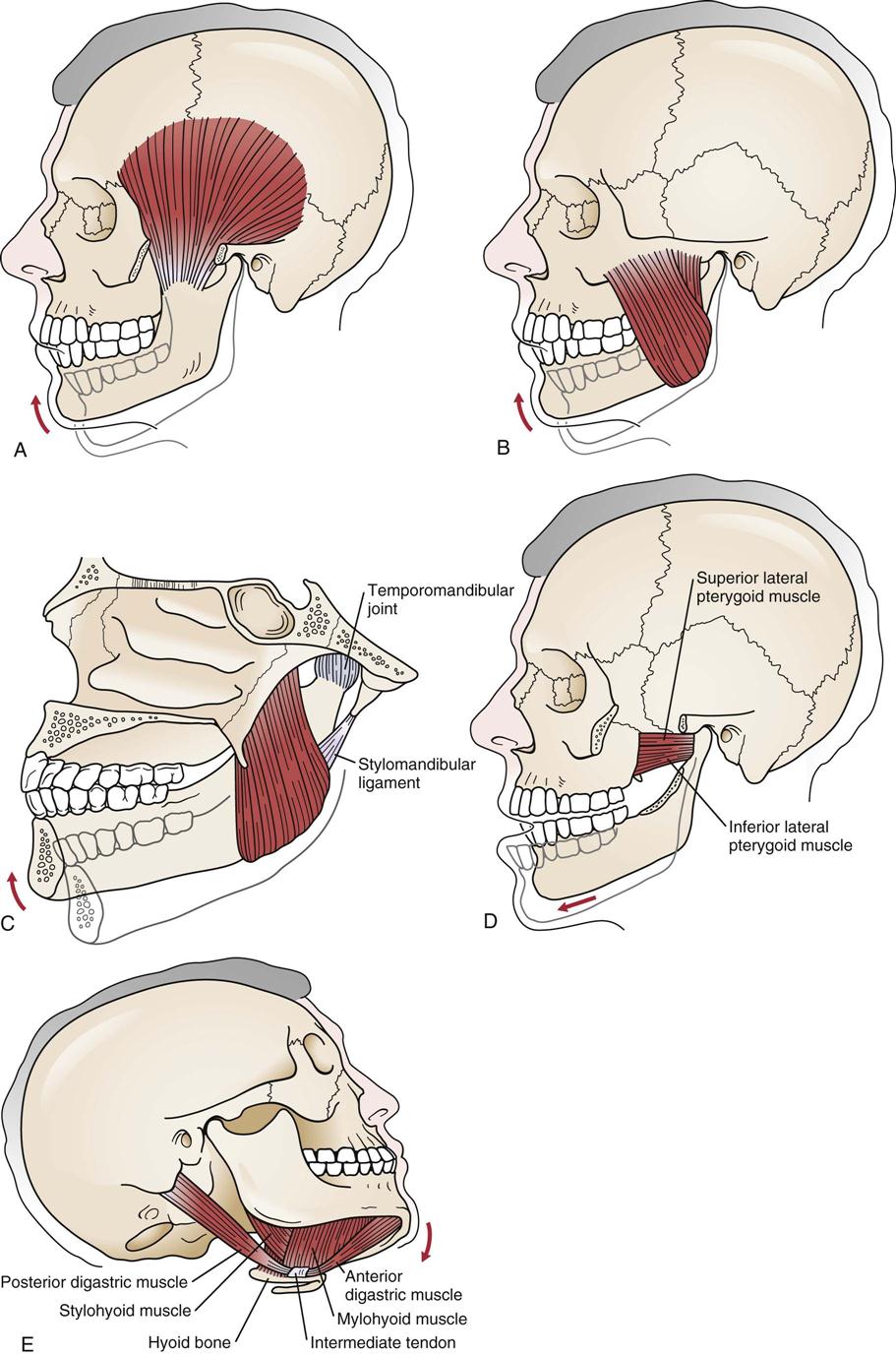

The examiner then places the index fingers over the mandibular condyles and feels for elicited pain or tenderness on opening and closing of the mouth. The examiner may also palpate the medial pterygoid, the medial and lower border of the inferior head of the lateral pterygoid, the temporalis and its tendon, and the masseter muscles and any other soft tissues for tenderness or indications of pathology (Figure 4-36). This procedure is followed by palpation of the following structures.

A, Temporalis muscle. B, Masseter muscle. C, Medial pterygoid muscle. D, Inferior and superior lateral pterygoid muscles. E, Digastric muscle. (Modified from Okeson JP: Management of temporomandibular disorders and occlusion, St Louis, 1998, CV Mosby, pp. 18–20, 22.)

Mandible.

The examiner palpates the mandible along its entire length, feeling for any differences between the left and right sides. As the examiner moves along the superior aspect of the angle of the mandible, the fingers pass over the parotid gland. Normally, the gland is not palpable, but with pathology (e.g., mumps), the site feels “boggy” rather than having the normal hard and bony feel.

Teeth.

The examiner should note the position, absence, or tenderness of the teeth. The examiner wears a rubber glove and palpates inside the patient’s mouth. At the same time, the interior cheek region and gums may be palpated for pathology.

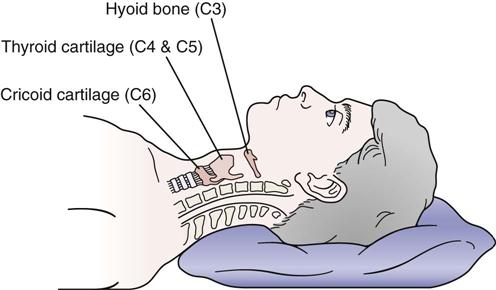

Hyoid Bone (Anterior to C2, C3 Vertebrae).

While palpating the hyoid bone (Figure 4-37), the examiner asks the patient to swallow. Normally, the bone moves and causes no pain. The hyoid bone is part of the superior trachea.

Thyroid Cartilage (Anterior to C4, C5 Vertebrae).

While the neck is in the neutral position, the thyroid cartilage can be easily moved; while in extension, it is tight, and the examiner may feel crepitations. The thyroid gland, which is adjacent to the cartilage, may be palpated at the same time. If abnormal or inflamed, it will be tender and enlarged.

Mastoid Processes.

The examiner should palpate the skull, following the posterior aspect of the ear. The examiner will come to a point on the skull where the finger dips inward. The point just before the dip is the mastoid process (see Figure 3-74).

Cervical Spine.

Beginning on the posterior aspect at the occiput, the examiner systematically palpates the posterior structures of the neck (spinous processes, facet joints, and muscles of the suboccipital region), working from the head toward the shoulders. On the lateral aspect, the transverse processes of the vertebrae, the lymph nodes (palpable only if swollen), and the muscles should be palpated for tenderness. A more detailed description of the palpation of these structures is given in Chapter 3.

Diagnostic Imaging

Plain Film Radiography

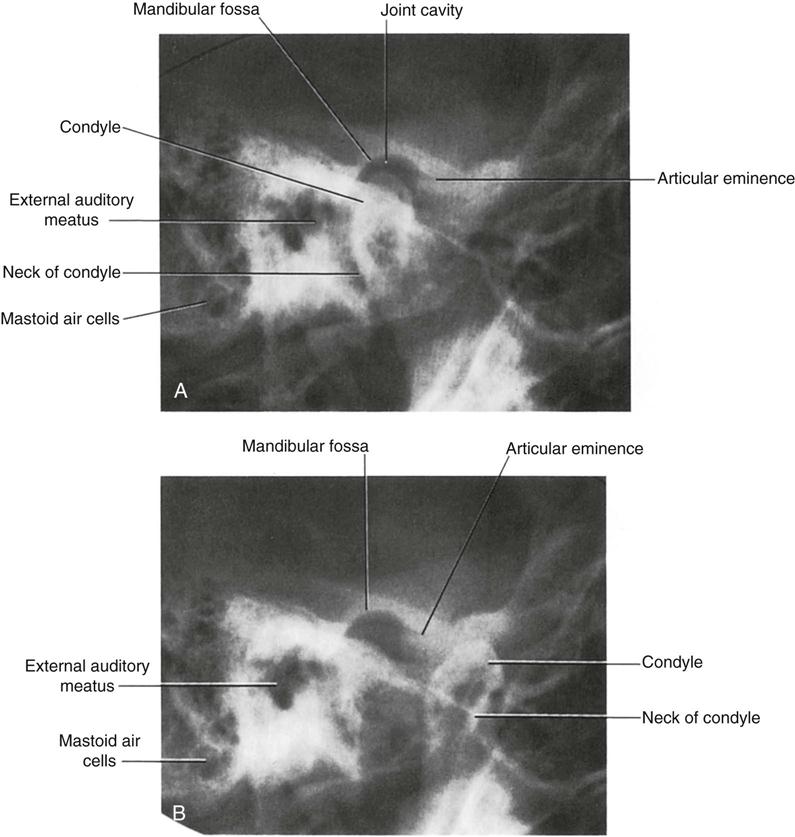

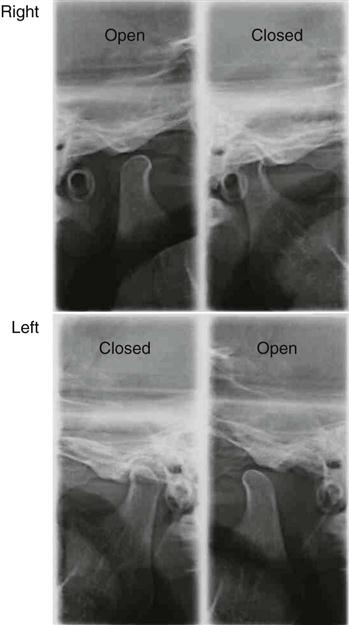

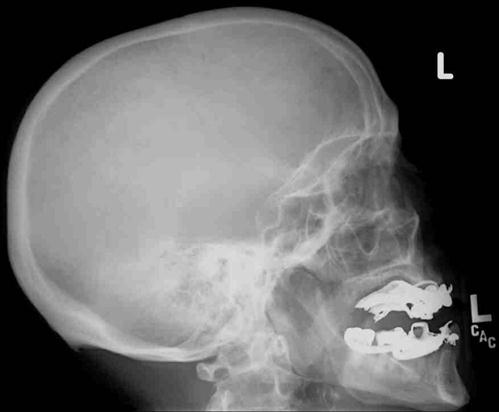

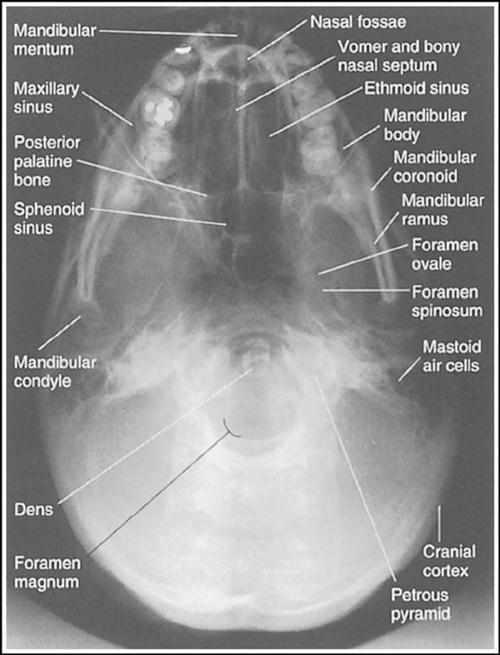

On the anteroposterior view, the examiner should look for condylar shape and normal contours. On the lateral view, the examiner should look for condylar shape and contours, position of condylar heads in the opened and closed positions (Figure 4-38), amount of condylar movement (closed versus open), and relation of temporomandibular joint to other bony structures of the skull and cervical spine (Figure 4-39). X-ray views commonly taken for the temporomandibular joint are shown in the following box.

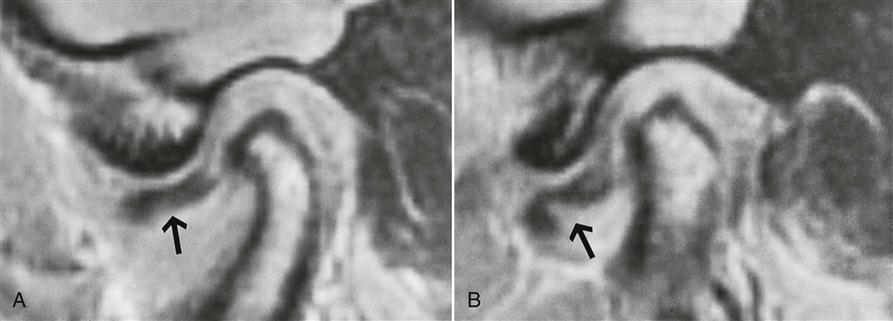

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

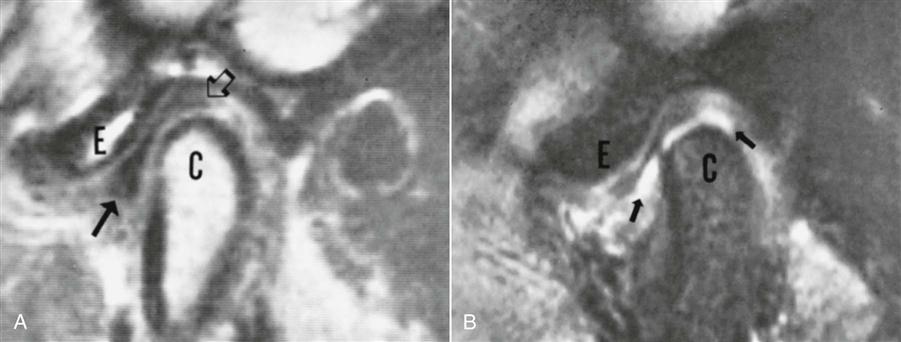

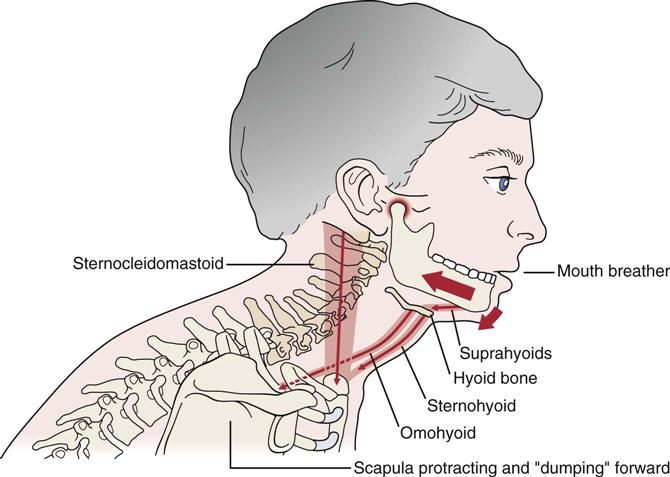

This technique is used to differentiate the soft tissue of the joint, mainly the disc, from the bony structures and therefore has become the gold standard for testing the reliability of clinical findings in the temporomandibular joint.41 It has the advantage of using nonionizing radiation (Figures 4-45 and 4-46).

A, T1-weighted sagittal spin echo magnetic resonance image with the mouth closed shows the dislocated disc (arrow) anterior to the condyle. B, With attempted mouth opening, no appreciable anterior translation of the condyle occurs, but the disc folds on itself in the thin intermediate zone because of increased pressure from the condyle. The normal biconcave configuration of the disc and the normal intradiscal signal intensity are maintained (arrow). (From Resnick D, Kransdorf MJ: Bone and joint imaging, Philadelphia, 2005, WB Saunders, p. 516.)

A, T1-weighted sagittal spin echo MR image of a normal TMJ. View with the mouth closed shows high signal intensity from the condylar marrow (C) and articular eminence (E). Surrounding cortical bone is devoid of signal. The disc, of low signal intensity, is interposed between the condyle and the fossa; the intermediate zone articulates with the condyle and eminence where they are most closely apposed. The solid arrow points to the anterior band and the open arrow to the posterior band of the disc. B, Sagittal gradient echo MR image used for fast (pseudodynamic) scanning shows a normal position of the disc with the mouth closed. Marrow becomes low in signal intensity with this sequence, and fluid in the inferior joint space becomes bright (arrows); the disc remains low in signal intensity. C, Sagittal gradient image of a normal TMJ with the mouth open. The intermediate zone of the disc maintains its position between the condyle (C) and the eminence (E), whereas the posterior band slides posterior to the condyle (arrow). D, T1-weighted sagittal spin echo MR image in a patient with clicking and pain demonstrates internal derangement with both the anterior (solid arrow) and posterior (open arrow) bands of the disc displaced anteriorly relative to the condyle (C). C, Condyle; E, eminence. (From Resnick D, Kransdorf MJ: Bone and joint imaging, Philadelphia, 2005, WB Saunders, p. 509.)

Figure 4-24

Figure 4-24

Figure 4-28

Figure 4-28