Chapter 36 Artificial Insemination

INTRODUCTION

Artificial insemination is an assisted conception method that can be used to alleviate infertility in selected couples. The rationale behind the use of artificial insemination is to increase the gamete density near the site of fertilization.1 The effectiveness of artificial insemination has been clearly established in specific subsets of infertile patients such as those with idiopathic infertility, infertility related to a cervical factor, or a mild male factor infertility (Table 36-1).2,3 An accepted advantage of artificial insemination is that it is generally less expensive and invasive than other assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures.4

Table 36-1 Infertility Disorders with Proven Benefit from Partner Insemination

| Idiopathic infertility |

| Cervical factor infertility |

| Mild male factor infertility |

From Cohlen BJ: Should we continue performing intrauterine inseminations in the year 2004? Gynecol Obstet Invest 59:3–13, 2004.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Techniques

In the latter half of the 20th century, the cervical cap was developed to maintain the highest concentration of semen at the external os of the cervix. It was soon discovered that placing the semen sample into the endocervix (intracervical insemination) resulted in pregnancy rates similar to that obtainable using a cervical cap and superior to those seen with high vaginal insemination.5

Intrauterine Versus Intracervical Insemination

A major breakthrough came in the 1960s when methods were developed for extracting enriched samples of motile sperm from semen. These purified samples were free of proteins and prostaglandins, and thus could be placed within the uterus using a technique designated intrauterine insemination (IUI). This technique was found to result in pregnancy rates 2 to 3 times those of intracervical insemination. However, intracervical insemination is still utilized in some practices.5

In an effort to further improve pregnancy rates, techniques were developed to place washed sperm samples directly into the tubes via transcerival cannulation (intratubal insemination) or into the peritoneal cavity via a needle placed through the posterior cul-de-sac (intraperitoneal insemination). Another technique developed in Europe, termed fallopian tube sperm perfusion, involves pressure injection of a large volume (4mL) of washed sperm sample while the cervix is sealed to prevent reflux of the sample.6 This technique appears to have a higher pregnancy rate than IUI in couples with unexplained infertility. The remainder of these technically difficult approaches have never been shown to result in better pregnancy rates than IUI. One prospective, randomized study found that simultaneous intratubal insemination actually decreased the pregnancy rates associated with IUI.7 In modern clinical practice in the United States, IUI is the predominant technique used for artificial insemination.

EVALUATION

Male Evaluation

Antisperm Antibodies

There are multiple known risk factors for the development of male antisperm antibodies.8 Vasectomy results in the development of antisperm antibodies in the majority of men. After successful vasovasostomy, more than half of these men will have detectable sperm-bound antibodies. The pregnancy rates will depend on many factors, including the titer and quantity of gross agglutination. Obstructive azospermia from any cause (e.g., congenital absence of the vas deferens, cystic fibrosis, infant hernia repair) increases the risk of antisperm antibodies. Reproductive infections (e.g., epididymitis, prostatitis, or orchitis) are also associated with antisperm antibodies.

Antisperm antibody tests are performed as a routine part of a complete semen analysis during the initial infertility evaluation. The most commonly used test in clinical practice is probably the immunobead assay.8 This quantitative assay evaluates live sperm and indicates percent bound, antibody isotype, and binding location. For routine screening, some andrology laboratories use a commercially available mixed antiglobulin reaction assay (SpermMar).

Male subfertility is significantly increased when the antisperm antibody level is greater than 50%.9,10 Antisperm antibodies interfere with sperm–zona pellucida binding and prevent embryo cleavage and early development.

Female Evaluation

The female partner should undergo a basic infertility evaluation so that any correctable factors can be identified and treated before artificial insemination (see Chapter 34). In addition to a detailed history and physical examination, each woman considering partner or donor insemination should be evaluated with an imaging technique, usually a hysterosalpingogram, to document patent tubes. Unless oral or injectable medications are used to induce superovulation, ovulatory function should be evaluated with a urinary luteinizing hormone (LH) detection kit and midluteal serum progesterone level. Further evaluation is required in the event of detection of any clinical or laboratory abnormalities.

INDICATIONS

Partner Insemination

Partner insemination was originally developed as a treatment for male factor infertility. With the advent of IUI, partner insemination has been found to be an excellent treatment for a range of diagnoses, including cervical factor infertility, unexplained infertility, and subfertility, on the basis of other diagnoses or therapeutic measures (Table 36-2). This ability of partner insemination to increase pregnancy rates regardless of diagnosis has made this technique one of the fundamental approaches to infertility treatment today.

Table 36-2 Indications and Contraindications for Partner Insemination

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

Male Factor Infertility

Partner insemination appears to be of clear benefit when the couple’s infertility is the result of any condition that makes it difficult to place semen high in the vagina during coitus. Male conditions resulting in this situation are termed ejaculatory failure. The most common causes of ejaculatory failure are impotence, severe hypospadias, and retrograde ejaculation. A unique condition that has been found to be treatable with artificial insemination is impotence secondary to spinal cord injury.11

Partner insemination is also commonly used as a treatment for male factor infertility documented by repeated abnormal results on semen analysis. In couples where there is mild male factor infertility, defined as a progressive sperm motility of at least 20% to 30%, the prognosis appears to be good with partner insemination. Theoretically, increasing the number of motile sperm reaching the egg should improve fertility whenever decreased numbers and motility of normally functioning sperm is the primary problem.

Unfortunately, the pregnancy rates after partner IUI for the treatment of severe male factor infertility have been disappointing.12 This is probably because markedly abnormal parameters on routine semen analysis often reflect a sperm defect that decreases the ability to fertilize eggs. This type of defect is unlikely to be overcome by increasing the number of sperm to which the egg is exposed at the site of fertilization. In patients with severely abnormal parameters on semen analysis and those with male factor infertility not amenable to partner insemination, more effective treatment will be either donor insemination or in vitro fertilization (IVF) with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

An Adjunct to Other Infertility Treatments

Partner IUI appears to be of value for increasing per cycle fecundity when inducing ovulation in women with ovulatory dysfunction.13 After ovulation induction with clomiphene citrate, partner IUI might work by overcoming the decreased cervical mucus associated with the use of clomiphene.14 With gonadotropins, partner IUI might compensate for subtle changes in sperm transport within the uterus or tubes related to marked alterations in circulating estrogen and progesterone levels associated with their use.

Partner IUI also appears to be of some benefit when women with mild and minimal endometriosis are trying to achieve pregnancy. After appropriate surgical treatment, the monthly improvement in fecundity with partner IUI appears to be similar to that seen in patients with idiopathic infertility.15

Unexplained Infertility

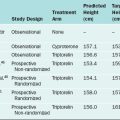

In couples with unexplained infertility, partner IUI has been demonstrated to improve pregnancy rates when used in conjunction with superovulation.13 In a meta-analysis of almost 1000 superovulation cycles for unexplained infertility, partner IUI was found to almost double pregnancy rates (20%) compared to timed intercourse alone (11%).

Donor Insemination

Some women choose donor insemination because they are not candidates for IVF/ICSI. Perhaps the most obvious situation is women without male partners who seek pregnancy. The use of donor insemination is also indicated when the male partner has no viable sperm (i.e., azoospermia) or when IVF/ICSI fails to achieve fertilization. Finally, men with a known genetic disorder often choose donor insemination to avoid transmission to their children.

Donor Evaluation

Thorough evaluation of all potential sperm donors (other than sexually intimate partners) is necessary to avoid inadvertent transmission of sexually transmitted diseases or known genetic syndromes.16 All donors undergo a review of relevant medical records, personal and family history, and a physical examination. Determination of normal semen characteristics is extremely important. In addition, blood grouping and karyotyping is performed.

Success Rate

The actual per cycle fecundity rate with donor IUI is dependent on multiple factors. A meta-analysis of seven studies demonstrated that IUI yielded a higher pregnancy rate per cycle than intracervical insemination with donor frozen sperm.17 Overall, the average live birth rate per cycle of donor IUI is approximately 10%.18

IUI TIMING, COST, AND FREQUENCY

Timing

Timing of insemination in relationship to ovulation is one of the crucial factors in the success of IUI. Although viable sperm remain in the female reproductive tract for up to 120 hours after coitus, the best pregnancy rates are obtained when IUI is performed as close as possible to ovulation.19,20

LH Surge

A commonly used method for timing of IUI is based on urinary LH measurement. Ovulation occurs 40 to 45 hours after the onset of the LH surge.21 Insemination is thus planned for the day after detection of a rise in urinary LH. This approach offers the simplest and most cost-effective of the indirect methods for predicting ovulation and is just as effective in achieving pregnancy as more complex ones.22,23

IUI Cost

The cost-effectiveness of the treatment is an important consideration when deciding on the most appropriate infertility treatment option.24 The cost of insemination varies from clinic to clinic, but is presently less than $500 per IUI, including sperm preparation and injection of the prepared sample. This compares favorably with the cost of other appropriate ART approaches. Even when the cost of ovulation induction medication and monitoring are included, the cost per live birth for IUI after superovulation has been calculated to be less than half the cost of IVF treatment.25

IUI Frequency

It is recommended that IUI be performed either one or two times during each cycle. Performing two inseminations per cycle is likely to be especially advantageous when timing in relationship to ovulation is less precise. Although it seems intuitive that fecundity should be increased by two inseminations per cycle, it remains inconclusive whether the increased fecundity is worth doubling the patients’ cost and inconvenience compared to one insemination per cycle.26–30 A recent meta-analysis of more than 1000 IUI cycles revealed a slightly higher but statistically insignificant difference between the per cycle fecundity rate for two inseminations (14.9%) compared to one insemination per cycle (11.4%).31 Accordingly, one well-timed insemination appears to offer the best balance between efficacy and cost.

SPERM PREPARATION FOR IUI

Sperm preparation methods are used to process semen samples such that viable sperm are separated from seminal plasma. This is necessary before IUI to avoid the consequences of intrauterine injecting of semen plasma proteins and prostaglandins.32 Although seminal plasma protects the spermatozoa from stressful conditions such as oxidative stress,33 it also contains factors that inhibit the fertilizing ability of the spermatozoa and reduce the induction of capacitation.34,35 Sperm preparation involves removing the seminal plasma efficiently and quickly and eliminating dead sperm, leukocytes, immature germ cells, epithelial cells, and microbial contamination. Several methods for sperm preparation are currently used (Table 36-3).

Table 36-3 Common Techniques Used for Sperm Preparation Prior to Intrauterine Insemination

| Washing |

The ideal sperm preparation method recovers highly functional spermatozoa and enhances sperm quality and function without inducing damage. It is also cost-effective and allows for the processing of a large volume of the ejaculate, which in turn maximizes the number of spermatozoa that are available.36 The ideal sperm preparation method minimizes the risk of reactive oxygen species generation, which can adversely affect DNA integrity and sperm function in vitro.33,37 Several preparation methods incorporate methylxanthines and pentoxifyllines to increase sperm motility and improve the fertilization outcome.

Which Preparation Method is the Best?

The preparation techniques most commonly used today are the double density gradient centrifugation and the glass wool filtration sperm washing techniques. These techniques have been shown to improve the number of morphologic normal spermatozoa with grade A motility and with normal chromatin condensation in the prepared sample.38–40 In addition, these techniques best reduce the amount of reactive oxygen species and leukocytes in the prepared sample and provide spermatozoa with minimal chromatin and nuclear DNA anomalies and high nuclear maturity rates.

For semen samples with normal or near-normal sperm parameters, one study has shown that swim-up and density gradient techniques result in higher pregnancy rates compared to the washing, swim-down, and refrigeration/heparin techniques.41 For poor samples, the density gradient centrifugation and glass wool filtration techniques appear to be superior. In cases of very low sperm counts, simple sperm washing will recover the highest number of sperm, both motile and nonmotile.

IUI TECHNIQUE

IUI is performed using one of several commercially available intrauterine insemination catheters connected to a 2-mL syringe (Fig. 36-1). With the fully awake patient in a dorsal lithotomy position, the cervix is visualized with a bivalve vaginal speculum. After excess vaginal secretions are wiped from the external cervical os, the tip of a thin flexible catheter is passed into the uterine cavity, and the sperm sample, suspended in less than 1 mL of wash media, is gently expelled high in the uterine cavity. Increased resistance during injection suggests that the catheter is kinked or the tip might be inadvertently lodged in the endometrium or tubal ostia. In this situation, the catheter should be withdrawn 1cm, and injection reattempted. After IUI, the catheter is slowly removed and the patient allowed to remain supine for 10 minutes after insemination in case she experiences a vasovagal reaction.

A second method for navigation of the endocervical canal for IUI is by using a semirigid yet flexible catheter that has no memory.42 Pressure is used to force the catheter to follow the course of the canal. This technique often requires the use of a cervical tenaculum to apply countertraction. Because the diameter of some of these types of catheters is usually larger in caliber (greater than 3 mm), dilatation is sometimes required in the presence of cervical stenosis.

FACTORS THAT PREDICT PREGNANCY RATES

The highest pregnancy rates with IUI are seen within three to four cycles.43 The average live birth rate per cycle is approximately 10%.18 Cumulative pregnancy rates depend on the characteristics of the couples being treated. In most reports, the cumulative pregnancy rate reaches plateau after three to six cycles.

It is difficult to predict with certainty whether pregnancy will occur. Several models have been proposed but have not been validated.44,45

Male Factors That Predict IUI Success

Semen Analysis Characteristics

Semen characteristics clearly affect IUI outcome.46 IUI is a successful treatment for mild male factor infertility, defined as a total motile sperm count of more than 5 million and Kruger morphology of more than 5%.47 In a study in patients with mild male factor infertility, a live birth rate of 19% per cycle was reported.47

When prepreparation semen analyses characteristics are evaluated, the chances of pregnancy after IUI correlate best with morphology. A meta-analysis of six studies using strict morphology criteria (Kruger) showed that when the prewashed semen specimen had more than 4% normal sperm morphology, the chances of pregnancy after IUI were significantly increased.48 If the WHO standards were used to evaluate sperm morphology, the presence of more than 30% abnormal sperm in the ejaculate adversely influenced the pregnancy rate.49

Total Motile Sperm Count

The sperm variable most clearly associated with pregnancy rates after IUI is the total motile sperm count after sperm wash or swim-up. In a retrospective study of 9963 IUI cycles, the likelihood of subsequent pregnancy was maximized when the IUI sample contained more than 4 million motile sperm numbers and sperm motility was greater than 60%.50 Total motile sperm count was reported to affect IUI outcome in 1115 cycles in 332 infertile couples.51 No pregnancy occurred in cases where the total motile sperm count before semen preparation was less than 1 ′ 106.

Sperm DNA Damage Tests

The sperm chromatin structure assay provides an objective assessment of sperm chromatin integrity and can be useful as a fertility marker.52 In a recent study, DNA damage as measured using this test was found to predict the outcome of IUI.

The DNA fragmentation index (DFI) has been shown to be negatively correlated with the overall pregnancy rate in women undergoing IUI, IVF, or ICSI.53 The chances of achieving pregnancy are significantly lower when the sperm DFI is greater than 27% after IUI processing.54

TUNEL evaluates the degree of sperm DNA fragmentation and stability.55 In one study, lower degrees of DNA fragmentation after IUI sperm preparation correlated with higher pregnancy rates, and no pregnancy occurred when more than 12% of sperm in an IUI specimen were TUNEL-positive.

Hypo-osmotic Swelling Test

The hypo-osmotic swelling test evaluates the membrane integrity of the sperm tail, detects the differences on the sperm surface, and detects subtle damage in membrane properties, which reduces the ability of spermatozoa to induce a viable embryo.56 A sample “passes” the hypo-osmotic swelling test when at least 50% of sperm in an IUI sample swell.57 Sperm specimens that fail the hypo-osmotic swelling test appear to have decreased fertilizing ability, and thus pregnancy rates after IUI are lower. The miscarriage rate was also higher when result of hypo-osmotic swelling test was less than 50%.

Antisperm Antibodies

Both IUI and IVF appear to be effective in treating subfertility in men with antisperm antibodies, although IVF/ICSI appears to have higher pregnancy rates per cycle than IUI.58 However, to date no large prospective, randomized, controlled trial has compared IUI to IVF/ICSI in men with antisperm antibodies. In severe cases of antisperm antibodies, especially when the sperm head is involved, IVF/ICSI will often be required to achieve pregnancy.59,60

Female Factors That Predict IUI Success

Many studies have examined the different variables affecting pregnancy rates after IUI.25,61–64 The influence of lifestyle habits (e.g., smoking, caffeine consumption, and weight) is unclear but is most probably significant. There appear to be several important female factors that are useful in predicting pregnancy rates after IUI. These factors are maternal age, duration of infertility, and fenale infertility factors.65

Maternal Age

A woman’s age is an indirect indicator for oocyte quality, and it has a significant effect on the pregnancy rates. An age-related decline in female fecundity has been documented in women undergoing IUI.43,64 Successful pregnancy rates decrease after age 35 and reduce dramatically after age 40. However, pregnancies can occur at relatively advanced maternal ages, and satisfactory pregnancy rates can be obtained with IUI among women age 40 to 42.66,67

Duration of Infertility

The longer the duration of infertility, the lower the pregnancy rates are after IUI.25,43,65 Although the precise limits of infertility duration for recommending IUI have not been clearly established, the pregnancy rate may be seriously compromised when infertility has lasted 3 or more years.

Female Fertility Factors

The success of artificial insemination depends not only on the quality of oocytes and spermatozoa, but also on the receptivity of the endometrium. In a retrospective study, the presence of uterine anomalies negatively affected the success of IUI.65

Endometrial thickness and pattern is also predictive of IUI success. In a study on women undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and IUI, a trilaminar endometrium on the day of IUI provided a favorable prediction of pregnancy. However, endometrial thickness and Doppler surveys of the spiral and uterine arteries and dominant follicle gave no useful predictive value.68 A study evaluated the role of endometrial volume measurement in predicting the pregnancy rate in women receiving controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and IUI.69 An endometrial volume of less than 2 mL on three-dimensional ultrasound on the day of insemination was associated with a poor likelihood of pregnancy.

RISKS AND COMPLICATIONS

Pelvic Infections

Limited cramping during or after an IUI procedure from the catheter or cervical tenaculum is common. These symptoms are self-limiting and should resolve within hours of the procedure. Continued discomfort can be an indication of a developing pelvic infection, which has been estimated to occur in less than 2 per 1000 IUI procedures.63 Early diagnosis and treatment are essential in these rare cases to minimize the risk to the patient, particularly that of subsequent decreased fertility.

Vasovagal Reaction

Vasovagal reactions can occur as a result of manipulation of the cervix. The resulting vasodilation and decreased heart rate can lead to hypotension, most commonly manifest by diaphoresis in a supine patient. Sitting or standing increases the risk of syncope, which is unlikely to occur supine. Persistent symptomatic vasovagal reactions in a supine patient will often respond to the patient crossing her legs.70 More severe cases might require treatment with intramuscular atropine injection (0.5 mg).

Allergic Reaction

Allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, can occur after IUI in response to potential allergens in the wash media. Reactions have been reported to both the bovine serum albumin and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) commonly used in the wash media.71,72 Of these, penicillin allergies are the most common in the general population. Allergic reactions after IUI can range from a mild skin rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis with laryngeal edema, bronchospasm, and hypotension. For the rare patient experiencing an allergic reaction after IUI, the use of wash media free of albumin and antibiotics is advised.

Antisperm Antibodies

When IUI was first introduced, there was a concern that the procedure could result in the development of serum antisperm antibodies. Fortunately, after 40 years of experience, it appears that exposure of the upper reproductive tract to washed spermatozoa during IUI does not stimulate the appearance of clinically significant female antisperm antibodies.73

Pregnancy-Related Complications

Multiple Pregnancies

The risk of multiple pregnancies is not increased by IUI. However, medications used to recruit multiple follicles before IUI do increase this risk. Clomiphene citrate is associated with a twin risk of 5% to 10% and rare higher-order multiples. Injectable gonadotropins are associated with multiple pregnancy rates of 14% to 39%.74–76 Careful monitoring of the number of periovulatory follicles and peak estradiol levels might decrease the rate of multiple pregnancies.61,74,77 In general, women are at high risk if they are younger than age 30, have more than six preovulatory follicles, and a peak serum estradiol level greater than 1000 pg/mL.

Spontaneous Abortion and Ectopic Pregnancy

The risk of spontaneous abortion appears to be increased after IUI compared to the fertile population and is in the range of 20% to 25%.1,78 The increased risk is probably not directly attributed to IUI but is most likely due to the underlying infertility problem. Likewise, ectopic pregnancy rates depend largely on the presence of predisposing factors such as tubal disease and do not appear to be attributed to the IUI procedure.79

PSYCHOLOGICAL, ETHICAL, AND LEGAL ISSUES OF DONOR INSEMINATION

Legal Issues

1 Allen NC, Herbert CM3rd, Maxson WS, et al. Intrauterine insemination: A critical review. Fertil Steril. 1985;44:569-580.

2 Keck C, Gerber-Schafer C, Wilhelm C, et al. Intrauterine insemination for treatment of male infertility. Int J Androl. 1997;20(Suppl 3):55-64.

3 Cohlen BJ. Should we continue performing intrauterine inseminations in the year 2004? Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;59:3-13.

4 Goverde AJ, McDonnell J, Vermeiden JP, et al. Intrauterine insemination or in vitro fertilisation in idiopathic subfertility and male subfertility: A randomised trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2000;355:13-18.

5 Coulson C, McLaughlin EA, Harris S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of cervical cap with intracervical reservoir versus standard intracervical injection to inseminate cryopreserved donor semen. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:84-87.

6 Cantineau AE, Heineman MJ, Al-Inany H, Cohlen BJ. Intrauterine insemination versus Fallopian tube sperm perfusion in non-tubal subfertility: A systematic review based on a Cochrane Review. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2721-2729.

7 Hurd WW, Randolph JFJr, Ansbacher R, et al. Comparison of intracervical, intrauterine, and intratubal techniques for donor insemination. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:339-342.

8 Ombelet W, Menkveld R, Kruger TF, Steeno O. Sperm morphology assessment: Historical review in relation to fertility. Hum Reprod Update. 1995;1:543-557.

9 Bronson R, Cooper G, Rosenfeld D. Sperm antibodies: Their role in infertility. Fertil Steril. 1984;42:171-183.

10 Barratt CL, McLeod ID, Dunphy BC, Cooke ID. Prognostic value of two putative sperm function tests: Hypo-osmotic swelling and bovine sperm mucus penetration test (Penetrak). Hum Reprod. 1992;7:1240-1244.

11 Ohl DA, Wolf LJ, Menge AC, et al. Electroejaculation and assisted reproductive technologies in the treatment of anejaculatory infertility. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:1249-1255.

12 Montanaro Gauci M, Kruger TF, Coetzee K, et al. Stepwise regression analysis to study male and female factors impacting on pregnancy rate in an intrauterine insemination programme. Andrologia. 2001;33:135-141.

13 Zeyneloglu HB, Arici A, Olive DL, Duleba AJ. Comparison of intrauterine insemination with timed intercourse in superovulated cycles with gonadotropins: A meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:486-491.

14 Sovino H, Sir-Petermann T, Devoto L. Clomiphene citrate and ovulation induction. Reprod Biomed Online. 2002;4:303-310.

15 Tummon IS, Asher LJ, Martin JS, Tulandi T. Randomized controlled trial of superovulation and insemination for infertility associated with minimal or mild endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:8-12.

16 ASRM. New guidelines for the use of semen donor insemination: 1990. The American Fertility Society. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:1S-13S.

17 Goldberg JM, Mascha E, Falcone T, Attaran M. Comparison of intrauterine and intracervical insemination with frozen donor sperm: A meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:792-795.

18 Rowell P, Braude P. Assisted conception. I—General principles. BMJ. 2003;327:799-801.

19 Weinberg CR, Wilcox AJ. A model for estimating the potency and survival of human gametes in vivo. Biometrics. 1995;51:405-412.

20 Gould JE, Overstreet JW, Hanson FW. Assessment of human sperm function after recovery from the female reproductive tract. Biol Reprod. 1984;31:888-894.

21 Lenton EA, Woodward B. Natural-cycle versus stimulated-cycle IVF: Is there a role for IVF in the natural cycle? J Assist Reprod Genet. 1993;10:406-408.

22 Zreik TG, Garcia-Velasco JA, Habboosh MS, et al. Prospective, randomized, crossover study to evaluate the benefit of human chorionic gonadotropin-timed versus urinary luteinizing hormone-timed intrauterine inseminations in clomiphene citrate-stimulated treatment cycles. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:1070-1074.

23 Deaton JL, Clark RR, Pittaway DE, et al. Clomiphene citrate ovulation induction in combination with a timed intrauterine insemination: The value of urinary luteinizing hormone versus human chorionic gonadotropin timing. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:43-47.

24 Van Voorhis BJ, Sparks AE, Allen BD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of infertility treatments: A cohort study. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:830-836.

25 Nuojua-Huttunen S, Tomas C, Bloigu R, et al. Intrauterine insemination treatment in subfertility: An analysis of factors affecting outcome. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:698-703.

26 Matilsky M, Geslevich Y, Ben-Ami M, et al. Two-day IUI treatment cycles are more successful than one-day IUI cycles when using frozen–thawed donor sperm. J Androl. 1998;19:603-607.

27 Ransom MX, Blotner MB, Bohrer M, et al. Does increasing frequency of intrauterine insemination improve pregnancy rates significantly during superovulation cycles? Fertil Steril. 1994;61:303-307.

28 Cohlen BJ, te Velde ER, van Kooij RJ, et al. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and intrauterine insemination for treating male subfertility: A controlled study. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1553-1558.

29 Arici A, Byrd W, Bradshaw K, et al. Evaluation of clomiphene citrate and human chorionic gonadotropin treatment: A prospective, randomized, crossover study during intrauterine insemination cycles. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:314-318.

30 Alborzi S, Motazedian S, Parsanezhad ME, Jannati S. Comparison of the effectiveness of single intrauterine insemination (IUI) versus double IUI per cycle in infertile patients. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:595-599.

31 Osuna C, Matorras R, Pijoan JI, Rodriguez-Escudero FJ. One versus two inseminations per cycle in intrauterine insemination with sperm from patients’ husbands: A systematic review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:17-24.

32 Alvarez JG. Nurture vs nature: How can we optimize sperm quality? J Androl. 2003;24:640-648.

33 Saleh R, Agarwal A. Oxidative stress and male infertility: From research bench to clinical practice. J Androl. 2002;23:737-752.

34 Mortimer D. Sperm preparation methods. J Androl. 2000;21:357-366.

35 Rogers BJ, Perreault SD, Bentwood BJ, et al. Variability in the human– hamster in vitro assay for fertility evaluation. Fertil Steril. 1983;39:204-211.

36 Yamamoto Y, Maenosono S, Okada H, et al. Comparisons of sperm quality, morphometry and function among human sperm populations recovered via SpermPrep II filtration, swim-up and Percoll density gradient methods. Andrologia. 1997;29:303-310.

37 Aitken RJ, Clarkson JS. Significance of reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in defining the efficacy of sperm preparation techniques. J Androl. 1988;9:367-376.

38 Erel CT, Senturk LM, Irez T, et al. Sperm-preparation techniques for men with normal and abnormal semen analysis. A comparison. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:917-922.

39 Sakkas D, Tomlinson M. Assessment of sperm competence. Semin Reprod Med. 2000;18:133-139.

40 Hammadeh ME, Kuhnen A, Amer AS, et al. Comparison of sperm preparation methods: Effect on chromatin and morphology recovery rates and their consequences on the clinical outcome after in vitro fertilization embryo transfer. Int J Androl. 2001;24:360-368.

41 Carrell DT, Kuneck PH, Peterson CM, et al. A randomized, prospective analysis of five sperm preparation techniques before intrauterine insemination of husband sperm. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:122-126.

42 Makler A. A simple technique to increase success rate of artificial insemination. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1980;18:19-21.

43 Plosker SM, Jacobson W, Amato P. Predicting and optimizing success in an intra-uterine insemination programme. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:2014-2021.

44 Agarwal A, Sharma RK, Nelson DR. New semen quality scores developed by principal component analysis of semen characteristics. J Androl. 2003;24:343-352.

45 Bedaiwy MA, Sharma RK, Alhussaini TK, et al. The use of novel semen quality scores to predict pregnancy in couples with male-factor infertility undergoing intrauterine insemination. J Androl. 2003;24:353-360.

46 Hendin BN, Falcone T, Hallak J, et al. The effect of patient and semen characteristics on live birth rates following intrauterine insemination: A retrospective study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2000;17:245-252.

47 Zayed F, Lenton EA, Cooke ID. Comparison between stimulated in vitro fertilization and stimulated intrauterine insemination for the treatment of unexplained and mild male factor infertility. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2408-2413.

48 Van Waart J, Kruger TF, Lombard CJ, Ombelet W. Predictive value of normal sperm morphology in intrauterine insemination (IUI): A structured literature review. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:495-500.

49 van Noord-Zaadstra BM, Looman CW, Alsbach H, et al. Delaying childbearing: Effect of age on fecundity and outcome of pregnancy. BMJ. 1991;302:1361-1365.

50 Stone BA, Vargyas JM, Ringler GE, et al. Determinants of the outcome of intrauterine insemination: Analysis of outcomes of 9963 consecutive cycles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1522-1534.

51 Campana A, Sakkas D, Stalberg A, et al. Intrauterine insemination: Evaluation of the results according to the woman’s age, sperm quality, total sperm count per insemination and life table analysis. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:732-736.

52 Richthoff J, Spano M, Giwercman YL, et al. The impact of testicular and accessory sex gland function on sperm chromatin integrity as assessed by the sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA). Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3162-3169.

53 Saleh RA, Agarwal A, Nada EA, et al. Negative effects of increased sperm DNA damage in relation to seminal oxidative stress in men with idiopathic and male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(Suppl 3):1597-1605.

54 Bungum M, Humaidan P, Spano M, et al. The predictive value of sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA) parameters for the outcome of intrauterine insemination, IVF and ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1401-1408.

55 Duran EH, Morshedi M, Taylor S, Oehninger S. Sperm DNA quality predicts intrauterine insemination outcome: A prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3122-3128.

56 Tartagni M, Schonauer MM, Cicinelli E, et al. Usefulness of the hypo-osmotic swelling test in predicting pregnancy rate and outcome in couples undergoing intrauterine insemination. J Androl. 2002;23:498-502.

57 Ombelet W, Deblaere K, Bosmans E, et al. Semen quality and intrauterine insemination. Reprod Biomed Online. 2003;7:485-492.

58 Ohl DA, Naz RK. Infertility due to antisperm antibodies. Urology. 1995;46:591-602.

59 McLachlan RI. Basis, diagnosis and treatment of immunological infertility in men. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;57:35-45.

60 Lombardo F, Gandini L, Dondero F, Lenzi A. Antisperm immunity in natural and assisted reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:450-456.

61 Dickey RP, Olar TT, Taylor SN, et al. Relationship of follicle number, serum estradiol, and other factors to birth rate and multiparity in human menopausal gonadotropin-induced intrauterine insemination cycles. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:89-92.

62 Dickey RP, Olar TT, Taylor SN, et al. Relationship of follicle number and other factors to fecundability and multiple pregnancy in clomiphene citrate-induced intrauterine insemination cycles. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:613-619.

63 Mathieu C, Ecochard R, Bied V, et al. Cumulative conception rate following intrauterine artificial insemination with husband’s spermatozoa: Influence of husband’s age. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1090-1097.

64 Tomlinson MJ, Amissah-Arthur JB, Thompson KA, et al. Prognostic indicators for intrauterine insemination (IUI): Statistical model for IUI success. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1892-1896.

65 Steures P, van der Steeg JW, Mol BW, et al. Prediction of an ongoing pregnancy after intrauterine insemination. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:45-51.

66 Haebe J, Martin J, Tekepety F, et al. Success of intrauterine insemination in women aged 40–42 years. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:29-33.

67 Khalil MR, Rasmussen PE, Erb K, et al. Homologous intrauterine insemination. An evaluation of prognostic factors based on a review of 2473 cycles. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:74-81.

68 Tsai HD, Chang CC, Hsieh YY, et al. Artificial insemination. Role of endometrial thickness and pattern, of vascular impedance of the spiral and uterine arteries, and of the dominant follicle. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:195-200.

69 Zollner U, Zollner KP, Blissing S, et al. Impact of three-dimensionally measured endometrial volume on the pregnancy rate after intrauterine insemination. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2003;125:136-141.

70 Krediet CT, van Dijk N, Linzer M, et al. Management of vasovagal syncope: Controlling or aborting faints by leg crossing and muscle tensing. Circulation. 2002;106:1684-1689.

71 Smith YR, Hurd WW, Menge AC, et al. Allergic reactions to penicillin during in vitro fertilization and intrauterine insemination. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:847-849.

72 Sonenthal KR, McKnight T, Shaughnessy MA, et al. Anaphylaxis during intrauterine insemination secondary to bovine serum albumin. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:1188-1191.

73 Moretti-Rojas I, Rojas FJ, Leisure M, et al. Intrauterine inseminations with washed human spermatozoa does not induce formation of antisperm antibodies. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:180-182.

74 Valbuena D, Simon C, Romero JL, et al. Factors responsible for multiple pregnancies after ovarian stimulation and intrauterine insemination with gonadotropins. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1996;13:663-668.

75 Goldfarb JM, Peskin B, Austin C, Lisbona H. Evaluation of predictive factors for multiple pregnancies during gonadotropin/IUI treatment. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1997;14:88-91.

76 Tur R, Buxaderas C, Martinez F, et al. Comparison of the role of cervical and intrauterine insemination techniques on the incidence of multiple pregnancy after artificial insemination with donor sperm. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1997;14:250-253.

77 Pasqualotto EB, Falcone T, Goldberg JM, et al. Risk factors for multiple gestation in women undergoing intrauterine insemination with ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:613-618.

78 Lalich RA, Marut EL, Prins GS, Scommegna A. Life table analysis of intrauterine insemination pregnancy rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:980-984.

79 Aboulghar MA, Mansour RT, Serour GI. Ovarian superstimulation in the treatment of infertility due to peritubal and periovarian adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1989;51:834-837.