CHAPTER 23 Arthroscopy for Symptomatic Hip Arthroplasty

Surgical technique

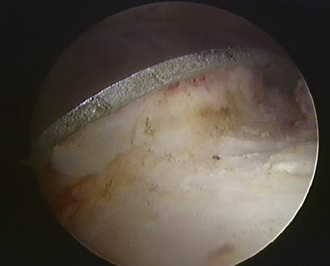

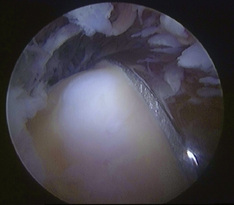

Standard lateral paratrochanteric and anterior paratrochanteric portals are made to access the central compartment; this allows for the visualization of the edge of the acetabular component, the bone–component interface (Figure 23-1), and the synovial membrane, and the surgeon is also able to look for any possible metallosis. If debridement is required, it is performed with an arthroscopic shaver or a radiofrequency probe. Synovial biopsy and further aspirates from the bone implant interface may also be obtained at this time.

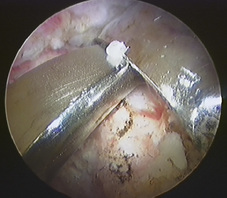

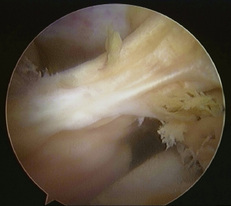

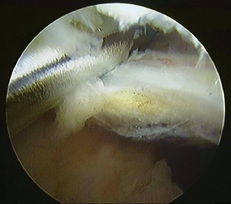

Releasing the traction completely and flexing the hip to relax the anterior capsule allows for easy access to the peripheral compartment of the arthroplasty. The main portal for the peripheral compartment is made approximately 4 cm anterior and superior to the direct lateral paratrochanteric portal. Entry into the peripheral compartment allows for the visualization of the base of the femoral component (Figure 23-2) for assessing component stability. It also provides an opportunity to diagnose and treat capsular pathology, fibrosis, adhesions (Figure 23-3), iliopsoas tendonitis (Figure 23-4), and soft-tissue and bony impingement lesions (Figure 23-5).

Results

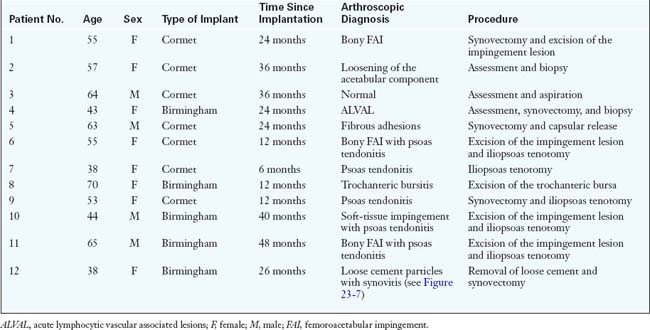

Twelve consecutive patients with painful resurfacing and normal or indeterminate investigations underwent arthroscopy of the hip in our unit. There were 8 female patients in the series, and the mean age of the patients was 53.7 years (range, 38 to 70 years). Seven patients had a fully uncemented hydroxyapatite-coated resurfacing arthroplasty (Cormet 2000, Corin Medical Ltd., Cirencester, UK), and 5 patients had a hybrid BIRMINGHAM HIP Resurfacing procedure (Midland Medical Technologies Ltd., Birmingham, UK). The mean period from the index operation to the arthroscopy was 25 months (range, 6 to 48 months). More complete details about all of the patients and their intraoperative diagnoses and treatments are shown in Table 23-1.

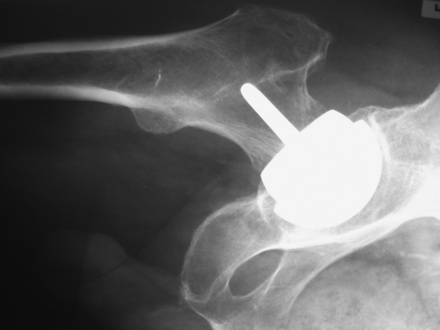

Two of the 12 patients were suspected of having an aseptic loosening of the acetabular component, but there was no obvious osteolysis apparent on the plain radiographs to confirm this (Figure 23-6). One of these patients was found to have that condition during arthroscopy, but both of the patients were revised to an uncemented total hip replacement; the femoral component, although well fixed, showed osteolysis at the base. None of the cultures of the aspirates sent at arthroscopy came back as being positive.

Fontana A., Zecca M., Sala C. Arthroscopic assessment of total hip replacement and polyethylene wear: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:244-245.

Hersch J.C., Dines D.M. Arthroscopy for failed shoulder arthroplasty. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:606-612.

Hyman J.L., Salvati E.A., Laurencin C.T., et al. The arthroscopic drainage, irrigation, and debridement of late, acute total hip arthroplasty infections: average 6-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:903-910.

Khanduja V., Villar R.N. The role of arthroscopy in resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(122):e1-e3.

Klinger H.M., Baums M.H., Spahn G., et al. A study of effectiveness of knee arthroscopy after knee arthroplasty. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:731-738.

Mastrokalos D.S., Zahos K.A., Korres D., et al. Arthroscopic debridement and irrigation of periprosthetic total elbow infection. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(1140):e1-e3.