CHAPTER 20 Arthroscopic Rim Resection and Labral Repair

Technique

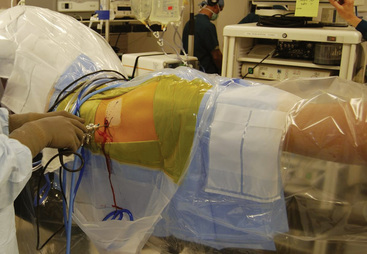

All of our arthroscopic hip techniques are performed with the patient in the supine position. After a lumbar plexus block and a general anesthetic are administered to the patient, we are very meticulous with our setup. The patients’ feet are wrapped in protective boots and placed in leather foot holders at the foot of the bed. Each lower extremity is attached to a bar that is freely mobile for abduction, adduction, flexion, and extension. The nonoperative extremity is placed in approximately 60 degrees of abduction, whereas the operative extremity will eventually be placed in neutral abduction. Before the feet are wrapped, electromyography monitors are placed near the tibial nerve for continuous monitoring during the procedure. After baseline signals are achieved, we are ready to begin the distraction of the operative extremity for optimal portal site placement. A C-arm fluoroscopy device is used to verify the amount of joint distraction that is achieved. The foot is internally rotated 90 degrees and then locked in place; this allows us to place the proximal femur nearly parallel with the floor. After the radiographic verification of adequate distraction is attained, we remove the C-arm and prepare the patient in a standardized fashion. A picture of our standard setup is shown in Figure 20-1.

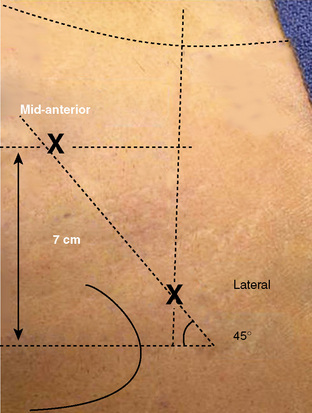

We draw out specific landmarks on the patient’s leg to properly identify the ideal location for our portals. The anterosuperior iliac spine and the outline of the greater trochanter are the most important of these landmarks. From the tip of the greater trochanter, we measure proximally 1 cm and anteriorly 1 cm; this is the ideal location for our lateral portal. From that site, we measure a distance between 5 cm and 6 cm distal and anterior on a 60-degree plane from horizontal for the placement of our unique mid-anterior portal (Figure 20-2). In our experience, these two portals are all that are necessary to achieve the adequate visualization of the most important aspects of both the central and peripheral compartments of the hip joint. We have also substantially reduced the morbidity associated with portal placement over the past year with the new position of our mid-anterior portal.

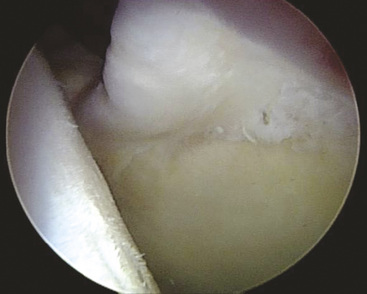

Now that we have established a portal for the arthroscope and a working portal, we can begin the diagnostic portion of the arthroscopy to visualize all aspects of both the central and peripheral compartments. Our attention is first directed to the chondrolabral junction. We use a probe to determine if there are any areas in which the labrum has been separated from the acetabular rim. It is typical with cam-type impingement to see delamination of the acetabular cartilage at the site of the labral detachment. With the use of the blunt end of a shaver or with a probe, it is possible to see a “wave sign”: the cartilage will buckle at sites where the labrum is damaged but not yet detached from the acetabular rim (Figure 20-3). It is very important to inspect these areas carefully. If they are not addressed at the time of the initial surgery, they can be the source of recurrent pain and disability as the junction between the labrum and the delaminated cartilage degenerates.

Rim trimming

The typical pincer lesion is produced as a result of an abnormal growth of bone at the anterosuperior portion of the acetabulum (Figure 20-4). The pincer can be either primary or secondary to the chronic abutment of the femoral neck on the acetabular rim. With respect to the normal anatomy and position of the acetabulum, this area creates a relative retroversion to the acetabulum. The x-rays in Figure 20-5 show this crossover sign. This is an area in which the anterior wall is farther lateral than the posterior acetabular rim. The goals of the rim resection should be to remove this area of bone and to restore the normal anatomy and relative position of the acetabulum with respect to the pelvis and the femoral neck. If this area is not addressed, subsequent labral damage and delamination of the cartilage will continue. Typically, this anterosuperior region of the acetabular rim also corresponds with the area of labral pathology. If the tear does not extend to this region, it is necessary to detach the labrum at this site for the proper resection of bone. After this has been completed, the labrum can then be reattached with the use of suture anchors.

Figure 20–5 Anteroposterior pelvic radiograph that shows a retroverted acetabulum and a crossover sign.

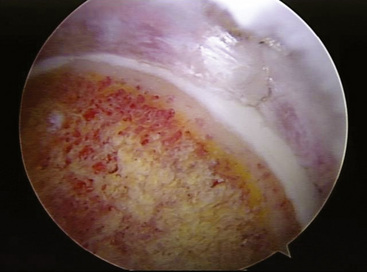

We perform the rim trimming with the use of a 5.5-mm motorized burr. With the labrum detached and safely out of the way, we slowly begin to remove bone from the anterosuperior margin of the rim. We continually stop and get a profile view of the acetabular rim with the arthroscope to determine the extent of our resection. This process is repeated until we have a normal acetabular profile and a healthy bed of tissue for reattaching the labrum. If the labral tear extends beyond the zone of the pincer lesion, we will also trim a small portion of the bone in that region as well to provide a good surface for our labral repair. An example of a typical rim resection is shown in Figure 20-6. It is not uncommon to encounter subchondral cysts during the rim resection; these cysts are evidence of chronic impingement and should be completely resected. If they are not addressed, it is possible to drill into them during suture anchor placement and thus achieve substandard fixation.

Labral repair

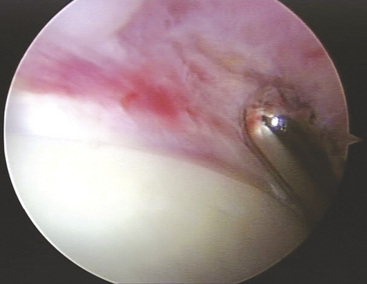

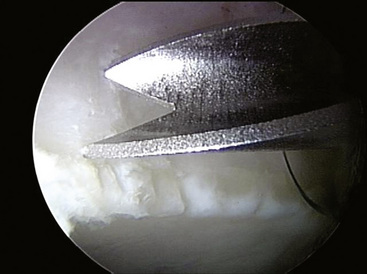

Our technique requires the use of a very-small-diameter suture anchor. Because the acetabular rim can be both shallow and narrow, larger anchor devices are not as efficacious with this application. We use the 2.3-mm PEEK BioRaptor (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA) for our fixation. We use a specially designed trocar with very sharp wings at the distal tip that help with the proper placement of the anchor; this allows us to get as close to the acetabular rim as possible without penetrating the joint (Figure 20-7).

Depending on the size of the tear, we will typically use two to three anchors to adequately fix the labrum down to the rim. We usually start at the most anterior aspect of the tear and work posteriorly. The anchor placement is the only time during the procedure that we will use a plastic cannula. A 10-mm cannula is placed through the mid-anterior portal, and the trocar is subsequently passed and placed in an optimal position on the rim. After the drilling and seating of the anchor, we test its integrity by pulling on the free limbs of the suture. We use an arthroscopic suture passer to pass the suture closest to the rim around the intra-articular portion of the labrum and to retrieve both limbs through the cannula. It is possible to tie the labrum with too much force and to strangulate the tissue; it is also possible to have the suture too loose and to have it become a secondary source of impingement during the procedure. An example of the appearance of an appropriately tensioned knot is shown in Figure 20-8. A standard arthroscopic suture cutter is placed as close to the knot as possible to reduce the potential size of any foreign material within the hip joint. We will repeat these steps with subsequent anchors until the labrum is well fixed.

After we have completed the labral repair, we test its integrity and its ability to seal the hip joint. By releasing the traction and moving the arthroscope into the peripheral compartment, we can evaluate the labral repair. From the peripheral compartment, it is possible to see the entire labrum and its interaction with the femoral head and neck as it moves through a full range of motion (see Figure 20-8). We also perform a dynamic examination by testing the hip joint in full flexion and abduction to ensure that the labrum does not demonstrate excessive motion and that there is no evidence of impingement present.

Technical Pearls

Outcomes

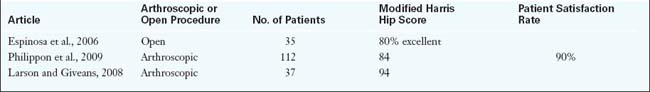

There are few reports that discuss the long-term outcomes of hip arthroscopy for labral dysfunction and associated femoroacetabular impingement (Table 20-1). We have recently reported about the outcomes of 45 professional athletes after arthroscopic intervention for femoroacetabular impingement and labral pathology. We used return to sport as an indicator for function, because these 45 professional athletes were unable to participate at the professional level before intervention. After arthroscopy, 93% of these patients returned to full competitive professional competition, and 78% remained active at the professional level an average of 1.6 years later.

Beck M., Leunig M., Parvizi J., Boutier V., Wyss D., Ganz R. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement: Part II. Midterm results of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2004;418:67-73.

Byrd J.W., Jones K.S. Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy.. 2000;16:578-587.

Byrd J.W., Pappas J.N., Pedley M.J. Hip arthroscopy: an anatomic study of portal placement and relationship to the extra-articular structures. Arthroscopy.. 1995;11:418-423.

Espinosa N., Rothenflug D.A., Beck M., Ganz R., Leunig M. Treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: preliminary results of labral refixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 2006;88:925-935.

Ganz R., Gill T.J., Gautier E., Ganz K., Krugel N., Berlemann U. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip: a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2001;83:1119-1124.

Lage L.A., Patel J.V., Villar R.N. The acetabular labral tear: an arthroscopic classification. Arthroscopy.. 1996;12:269-272.

Larson C.M., Giveans M.R. Arthroscopic management of femoroacetabular impingement. Early outcomes measures. Arthroscopy.. 2008;24(5):540-546.

McCarthy J.C., Lee J.A. Hip arthroscopy: indications, outcomes, and complications. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:301-308.

Murphy K.P., Ross A.E., Javernick M.A., Lehman R.A.Jr. Repair of the adult acetabular labrum. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(567):e1-567. e3.

Murphy S., Tannast M., Kim Y.J., Buly R., Millis M.B. Debridement of the adult hip for femoroacetabular impingement: indications and preliminary clinical results. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2004;429:178-181.

Parvizi J., Leunig M., Ganz R. Femoroacetabular impingement. J Am Acad Orthop Surg.. 2007;15:561-570.

Peters C.L., Erickson J.A. Treatment of femoroacetabular impingement with surgical dislocation and debridement in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 2006;88:1735-1741.

Philippon M., Schenker M., Briggs K., Kuppersmith D. Femoroacetabular impingement in 45 professional athletes: associated pathologies and return to sport following arthroscopic decompression. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroc.. 2007;15:908-914.

Philippon M.J., Briggs K.K., Kuppersmith D.A., Hines S.L., Maxwell R.B. Outcomes following hip arthroscopy with microfracture. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(6):e11.

Philippon M.J., Briggs K.K., Yen Y.M. Outcomes following hip arthroscopy for FAI and associated chondrolabral dysfunction. JBJS BR.. 2009;91:16-23.

Philippon M.J., Maxwell R.B., Johnston T.L., Schenker M., Briggs K.K. Clinical presentation of femoroacetabular impingement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.. 2007;15:1041-1047.

Philippon M.J., Schenker M.L., Briggs K.K., Kuppersmith D.A., Maxwell R.B., Stubbs A.J. Revision hip arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med.. 2007;35:1918-1921.

Philippon M.J., Schenker L., Briggs K.K., Maxwell R.B. Can microfracture produce repair tissue in acetabular chondral defects? Arthroscopy.. 2008;24.:46-50.

Philippon M.J., Stubbs A.J., Schenker M.L., Maxwell R.B., Ganz R., Leunig M. Arthroscopic management of femoroacetabular impingement: osteoplasty technique and literature review. Am J Sports Med.. 2007;35:1571-1580.

Seldes R.M., Tan V., Hunt J., Katz M., Winiarsky R., Fitzgerald R.H.Jr. Anatomy, histologic features, and vascularity of the adult acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop Realt Res. 2001;382:232-240.

Sussmann P.S., Ranawat A.S., Shehaan M., Lorich D., Padgett D.E., Kelly B.T. Vascular preservation during arthroscopic osteoplasty of the femoral head-neck junction: a cadaveric investigation. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:738-743.

Wahoff M., Briggs K.K., Philippon M.J. Hip arthroscopy rehabilitation. In Orthopaedic Knowledge Update. Chicago, IL: AAOS; 2009.