CHAPTER 25 Arthroscopic Management of Pediatric Hip Disease

Surgical technique

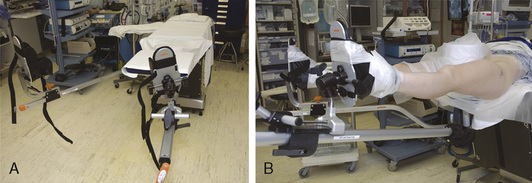

Hip arthroscopy can be performed with the patient in the supine or lateral decubitus position. Both positions allow for adequate visualization and positioning, and the one that is used is based on surgeon preference. We perform hip arthroscopy with the patient in the supine position, and it is generally performed as an outpatient procedure for the pediatric population. General anesthesia is used with muscle relaxation, although supplementation with regional anesthesia may be used, depending on the anesthesia available and patient preference. A standard fracture table or a specialized hip-scope table is used with a traction device and a large padded perineal post (Figure 25-1). The affected leg is prepped and draped along with a C-arm (Figure 25-2). The nonoperated side is placed in approximately 30 degrees of abduction, and firm traction is applied to that side so that the patient remains firmly against the perineal post. The operated leg is placed in neutral abduction to maintain a constant relationship between the topographic landmarks and the joint. A slight 10 degrees of flexion is used to relax the capsule; however, excessive flexion and traction can place tension on the sciatic nerve. Maximal internal rotation is used to make the femoral neck parallel with the floor. Traction is applied to achieve joint distraction between 5 mm and 10 mm, and this is confirmed by fluoroscopy; this will typically demonstrate the “vacuum sign” when viewed with the use of fluoroscopy. In general, approximately 50 lb to 75 lb of force is needed to distract a joint. The goals are to use the minimal force necessary to achieve distraction and to keep traction times as brief as possible (in general, less than 2 hours is considered optimal).

Portals

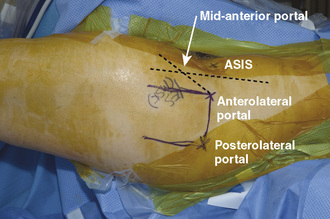

Two to three operating portals are typically used. The anterolateral and posterolateral portals are placed at the superior margin of the greater trochanter at the anterior and posterior borders (Figure 25-3). The mid-anterior portal is made by first drawing a sagittal line from the anterosuperior iliac spine and another line at the anterolateral portal; a sagittal line is then drawn equidistant to these two lines. The entry point for the mid-anterior portal is approximately 45 degrees from the anterolateral portal on the middle sagittal line. With careful attention paid to these landmarks, the portals can be safely made away from neurovascular structures. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve typically lies just medial to the anterosuperior iliac spine; the femoral nerve and artery are even more medial.

Diagnostic and Surgical Arthroscopy

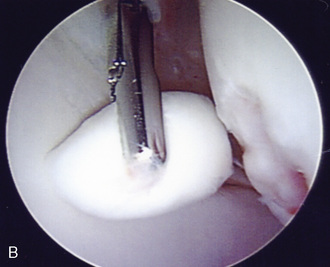

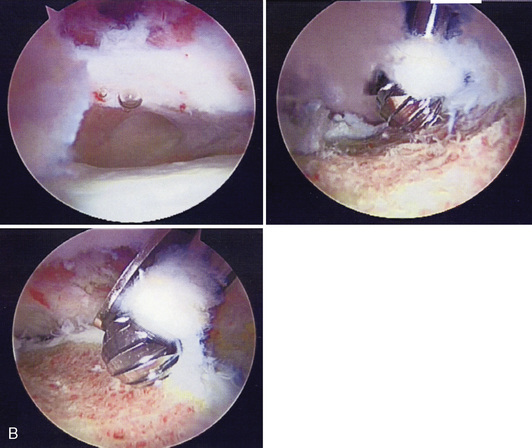

Loose bodies still represent the clearest indication for hip arthroscopy. Most of the problematic loose bodies are intra-articular and can be addressed with standard arthroscopic methods (Figure 25-4), and many can be debrided with shavers or flushed out through large-diameter cannulas. Both the intra-articular and peripheral compartments must be addressed, because loose bodies can easily hide within the peripheral joint. Large fragments frequently need to be morselized or removed freehand with sturdy graspers. If the surgeon is removing pieces in a freehand manner, the portal may need to be enlarged and the capsule further incised to prevent the loss of the fragment in the capsule or the subcutaneous tissue.

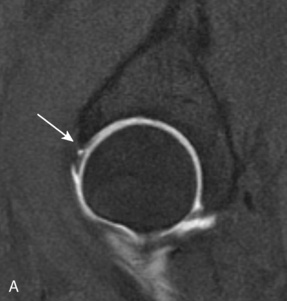

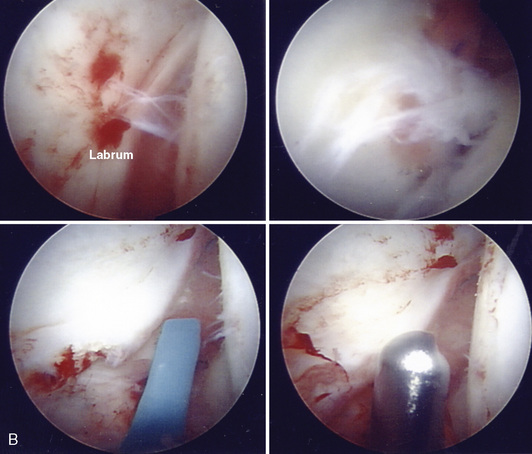

Labral pathology represents one of the most common reasons that athletes undergo hip arthroscopy. Labrum degeneration can occur as part of the aging process, and evidence of labral pathology exists in patients without symptoms. In general, pediatric patients experience more traumatic labral tears, but conditions such as femoroacetabular impingement have been recognized to predispose even young individuals to labral tearing. Labral tears can be addressed in a way that is similar to that of a meniscus in the knee. The goal is to remove diseased labrum to a stable rim of healthy tissue (Figure 25-5). Debridement can be performed with an arthroscopic shaver or thermal ablation with a flexible wand; however, care should be taken with thermal devices to avoid deep heat penetration. The evolution of debridement of the labrum has been to repair it.

Peripheral Compartment

After the work on the intra-articular side is completed, traction is released, and the hip is flexed to approximately 30 degrees to 45 degrees if surgery is to continue in the peripheral compartment. For synovial disease and loose-body removal, this compartment must be checked thoroughly. For patients with femoroacetabular impingement, the cam lesion can be addressed arthroscopically (Figure 25-6). Beginning with the arthroscope in the mid-anterior portal, the lateral edge of the cam lesion can be removed with an arthroscopic burr. Care must be taken not to remove too much bone and cartilage. The resection should begin above the lateral retinacular vessels and proceed medially across the neck; over-resection may predispose the patient to a femoral neck fracture. In the pediatric population, care should be taken not to disrupt the physis; localization with fluoroscopy may be necessary during the osteoplasty procedure.

Closure

Technical Pearls

Results

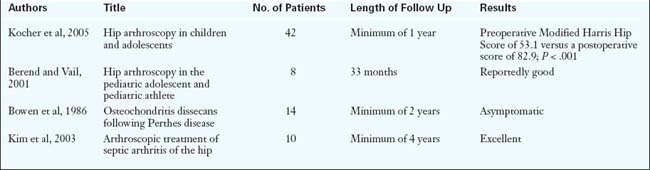

There have been relatively few results published regarding the use of hip arthroscopy for pediatric hip disease. The studies are listed in Table 25-1, and, in general, they have had good results.

Annotated references and suggested readings

Berend K.R., Vail T.P. Hip arthroscopy in the adolescent and pediatric athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20(4):763-778.

Bould M. Arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment of septic arthritis of the hip joint. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(6):707-708.

Bowen J.R., Kumar V.P., Joyce J.J.III, et al. Osteochondritis dessicans following Perthes disease. Clin Orthop. 1986;209:49-56.

Fischer S.U., Beattie T.F. The limping child: epidemiology, assessment, and outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81B(6):1029-1034.

Futami T., Kasahara Y., Suzuki S., et al. Arthroscopy for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:592-597.

Griffin D.R., Villar R.N. Complications in arthroscopy of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81B(4):604-606.

Gross R.H. Arthroscopy in hip disorders in children. Orthop Rev. 1977;6:43-49.

Holgersson S., Brattstrom H., Mogensen B., et al. Arthroscopy of the hip in juvenile chronic arthritis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1981;1(3):273-278.

Ikeda T., Awaya G., Suzuki S., et al. Torn acetabular labrum in young patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70B(1):13-16.

Kim S.J., Choi N.H., Ko S.H., et al. Arthroscopic treatment of septic arthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;407:211-214.

Kocher M.S., Bishop J.A., Weed B., et al. Delay in diagnosis of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Pediatrics. 2004;133(4):322-325.

Kocher M.S., Kim Y.J., Millis M.B., et al. Hip arthroscopy in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(5):680-686.

Kuklo T.R., Mackenzie W.G., Keeler K.A. Hip arthroscopy in Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(1):88-92.

Mintz D.N., Hooper T., Connell D., Buly R., Padgett D.E., Potter H.G. Magnetic resonance imaging of the hip: detection of labral and chondral abnormalities using noncontrast imaging. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(4):385-393.

Schindler A., Lechevallier J.J.C., Rao N.S., et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic arthroscopy of the hip in children and adolescents: evaluation of results. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:317-321.