CHAPTER 14 Arthroscopic Labral Repair

Diagnosis of labral tears of the hip

The clinical presentation of patients with a tear of the labrum is variable, and, as a result, the diagnosis is often missed initially. Burnett and colleagues reported about a series of 66 patients in whom the diagnosis of a labral tear had been made by arthroscopy. In this series, the mean time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 21 months. An average of 3.3 health care providers had seen each patient before the diagnosis of a labral tear was made. Groin pain was the most common complaint (92%), with the onset of symptoms most often being insidious. A positive “impingement sign” occurred in 95% of patients in this series; this sign consists of groin pain with flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the symptomatic hip (Figure 14-1). Therefore, in young, active patients who present with complaints of groin pain, with or without a history of trauma, the diagnosis of a labral tear of the hip should be suspected and investigated further.

Surgical technique

Technique for Arthroscopic Labral Debridement

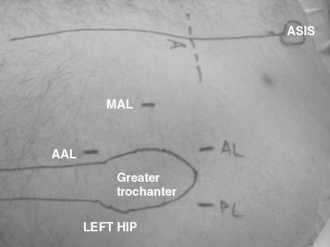

The procedure can be performed with the patient in either the supine or lateral position, depending on the level of comfort of the surgeon. The procedure should employ both a 30-degree and a 70-degree arthroscope for a thorough assessment of both the labrum and associated pathology. Modified arthroscopic flexible instruments, extended shavers, and hip-specific instrumentation should be available to improve access to all areas of the hip joint. In addition, the positioning of instruments should be done in the proper portals, with consideration for the anatomic structures near the hip joint (Figure 14-2).

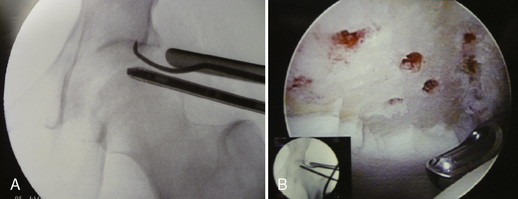

Adjacent cartilage damage should be searched for and thoroughly addressed. Superficial lesions can be gently debrided with mechanical shavers and perhaps stabilized with the use of radiofrequency probes. Grade IV Outerbridge lesions should be managed with a thorough debridement down to a bleeding bed and by preparation with microfracture awls (Figure 14-3).

Technique for Arthroscopic Labral Repair

The arthroscopic techniques include the use of routine anterior and anterolateral portals as well as an accessory mid-anterior portal that is halfway between the two portals and about 2 cm distal (see Figure 14-2). The routine use of several accessory portals is supported by the fact that the anterior anatomy allows for safe portal establishment anywhere between the standard anterior portal and the posterolateral portal.

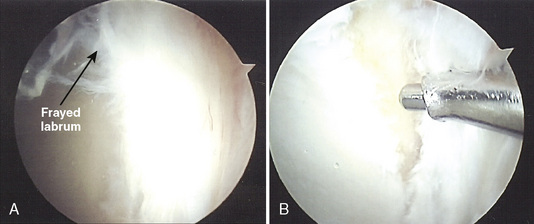

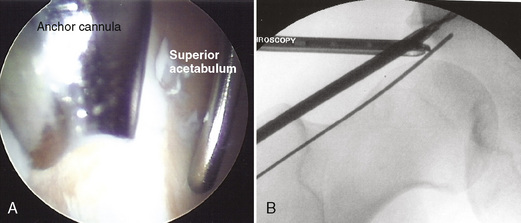

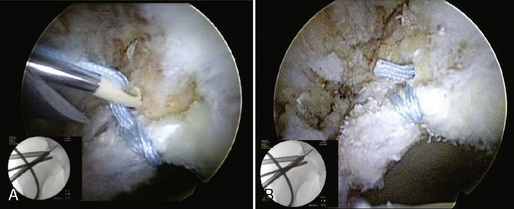

When the labral tear involves a detachment from the acetabulum either as a result of trauma or attritional tearing, a suture anchor is required for the stabilization of the tear. The area of the tearing is abraded and prepared with the use of either an aggressive shaver or a small burr. Fibrinous tissue is typically present at the bone–labrum interface, and an attempt is made to prepare the bed with a healthy vascular supply (Figure 14-4). The position of the anchor is critical to reestablishing the normal anatomy of the labrum. It should be placed on the acetabular rim to achieve an appropriate angle of approach while not penetrating into the articular cartilage. Avoiding chondral injury both in the head (upon delivery of the anchor) and with respect to acetabular penetration is important, because it can become a factor in joint degeneration. Both endoscopic and fluoroscopic visualization are essential (Figure 14-5). Options for repair include traditional suture anchors, which include knot tying or, more recently, the use of knotless anchors that allow for relatively easier technical maneuvers within the tight confines of the hip joint (Figure 14-6).

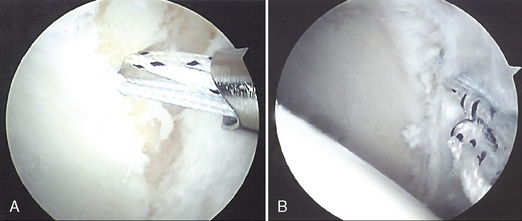

After the anchor is placed, a suture-passing device should be employed for the penetration of the labrum. A variety of devices exist for this purpose, with some employing shuttle devices and some simply penetrating through the tissue (Figure 14-7). Most of the instruments have been adapted from shoulder arthroscopy instrumentation. When the suture anchor is in place and the sutures have been passed, standard knot-tying techniques are employed (Figure 14-8).

Figure 14–7 Suture penetrator in place within the substance of a labrum that is detached from the acetabular bony wall.

Figure 14–8 Labral repair with the use of a suture anchor with penetrator devices. A, Anchor in place. B, Final repair.

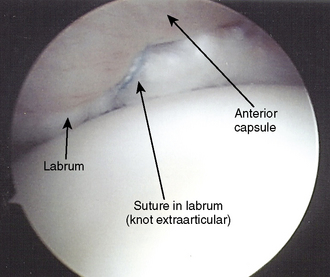

For cases in which an intrasubstance split is to be addressed, the cleavage plane in the labrum should be fully defined and debrided of all nonviable tissue. A suture shuttle device can be used to deliver a looped monofilament suture between the junction of the articular cartilage and the fibrocartilage labrum. A suture penetrator is then employed through the capsule to grasp the loop of monofilament. The looped suture is then used to shuttle a monofilament suture around the labral tearing and through the capsule. At this point, the suture is tied in an extra-articular position with the use of tactile feel and an automatic suture cutter (Figure 14-9).

Rehabilitation after debridement

Results

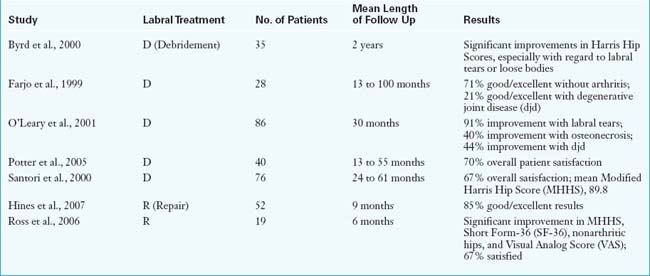

To date, there are no published series about the long-term outcomes of the arthroscopic repair of hip labral tears. Indications for the lesions that are considered to be repairable are currently evolving. Recently, Hines and colleagues presented outcome results with a mean follow up of 9 months for a series of 52 patients who underwent arthroscopic hip labral repair. Another study by Ross, which looked at the results of 19 patients, has also recently been published. The results of these studies and of those that have documented the outcomes of labral debridements are summarized in Table 14-1.

Annotated references and suggested readings

Burnett R.S., Della Rocca G.J., Prather H., et al. Clinical presentation of patients with tears of the acetabular labrum. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 2007;88A:1448-1457.

Byrd J.W., Jones K.S. Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:578-587.

Crawford M.J., Dy C.J., Alexander J.W., et al. The biomechanics of the hip labrum and the stability of the hip. J Orthop Res.. 2007;465:16-22.

Espinosa N., Rothenfluh D.A., Beck M., et al. Treatment of femoro-acetabular impingement: Preliminary results of labral refixation. J Bone Joint Surg.. 2006;88A:925-935.

Farjo L.A., Glick J.M., Sampson T.G. Hip arthroscopy for acetabular labral tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:132-137.

Ferguson S.J., Bryant J.T., Ganz R., et al. The influence of the acetabular labrum on hip joint cartilage consolidation: a poroelastic finite element model. J Biomech.. 2000;33:953-960.

Griffin D.R., Villar R.N. Complications of arthroscopy of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg.. 1991;81B:604-606.

Hines S.L., Philippon M.J., Kuppersmith D., et al. Early results of labral repair. Presented at 2007 annual AANA meeting. April 27, San Francisco, CA; 2007.

Kelly B.T., Shapiro G.S., Digiovanni C.W., et al. Vascularity of the hip labrum: a cadaveric investigation. Arthroscopy.. 2005;21(1):3-11.

Kelly B.T., Weiland D.E., Schenker M.L., et al. Current concepts: arthroscopic labral repair in the hip: surgical technique and review of the literature. Arthroscopy.. 2005;21:1496-1504.

Lage L.A., Patel J.V., Villar R.N. The acetabular labral tear: an arthroscopic classification. Arthroscopy.. 1996;12:269-272.

This is a descriptive classification of the commonly encountered types of labral tears..

McCarthy J.C., Noble P.C., Schuck M.R., et al. The watershed labral lesion: its relationship to early arthritis of the hip. J Arthroplasty.. 2001;16(8 Suppl 1):81-87.

Murphy K.P., Ross A.E., Javernick A., et al. Repair of the adult acetabular labrum. Arthroscopy.. 2006;22:e3.

O’Leary J.A., Bernard K., Vail T.P. The relationship between diagnosis and outcome in arthroscopy of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:181-188.

Potter B.K., Freedman B.A., Andersen R.C., et al. Correlation of short form-36 and disability status with outcomes of arthroscopic labral debridement. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:864-870.

Ross A.E., Javernick M., Freedman B., et al. Arthroscopic hip labral repair. Arthroscopy.. 2006;22:e30.

Santorini N, Villar R.N. Acetabular labral tears: result of arthroscopic partial limbectomy. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:11-15.

Seldes R.M., Tan V., Hunt J., et al. Anatomy, histologic features, and vascularity of the adult acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop.. 2001;382:232-240.

Toomayan F.A., Holman W.R., Major N.M., et al. Sensitivity of MR arthrography in the evaluation of acetabular labral tears. AJR Am J Roentgenol.. 2006;186(2):449-453.