CHAPTER 17 Arthroscopic Hip “Rotator Cuff Repair” of Gluteus Medius Tendon Avulsions

Introduction

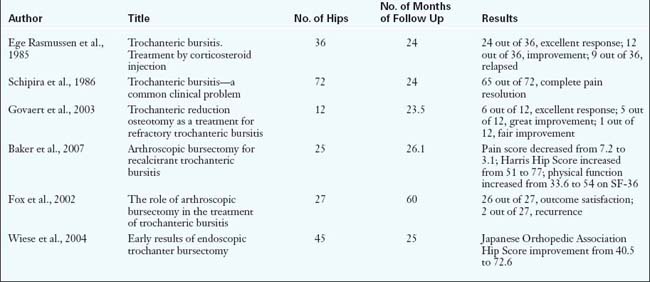

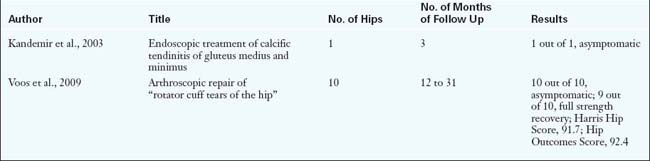

Hip arthroscopy has recently been expanded to allow for the visualization and treatment of extra-articular pathology, specifically in the peritrochanteric compartment. Disorders in this compartment include external coxa saltans or snapping hip, trochanteric bursitis, and gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tears (Tables 17-1, 17-2, and 17-3). These pathologies, which were underappreciated before hip arthroscopy, have now been identified as significant causes of lateral hip pain. The previous treatment of these disorders with conservative modalities or open surgery has had varied efficacy, and it has been associated with significant postoperative morbidity. Conservative treatment is often the preferred treatment modality and includes corticosteroid and anesthetic injections in combination with a structured physical therapy regimen. Patients for whom conservative treatment is ineffective have previously required open surgery.

| Treatment | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Rest, activity modification, stretching, corticosteroid injection, physical therapy | Varied |

| Open | Excision of ellipsoid portion of iliotibial band and trochanteric bursa | 80% improvement or full symptomatic relief |

| Arthroscopic | Transverse step cuts in the fascia and one longitudinal fascial incision | 88% with full symptomatic relief |

| Iliotibial band release (Z-plasty) | 95% full symptomatic relief |

Table 17–2 Trochanteric Bursitis

| Treatment | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Local corticosteroid and anesthetic injection with physical therapy | 66% excellent response and 33% improved symptoms |

| Open | Trochanteric reduction osteotomy | 50% excellent, 42% great, 8% fair improvement |

| Arthroscopic | Endoscopic bursectomy | Significant improvement in Harris Hip Score, visual analog scale results, and SF-36 score |

Table 17–3 Gluteus Medius and Minimus Tears

| Treatment | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Local corticosteroid and anesthetic injection with physical therapy | Up to 90% pain relief |

| Open | Tendon repair | No clinical data |

| Arthroscopic | Debridement of calcification and degenerated tendon | 100% asymptomatic |

| Tendon repair | 100% asymptomatic; 9 out of 10, full strength recovery |

Indications

Imaging and diagnostic studies

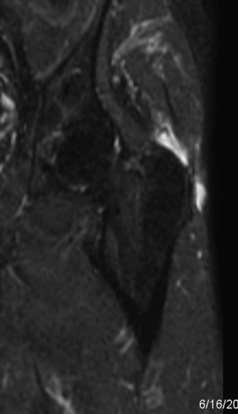

All patients who present with hip pain are evaluated with an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis as well as a Dunn lateral radiograph (90 degrees of hip flexion, 20 degrees of abduction, and the beam centered on and perpendicular to the hip) to assess for avulsions of the greater trochanter, cam and pincer lesions, loss of joint space, crossover sign, acetabular dysplasia, and sacroiliac joint pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging provides the most information about the soft tissues that surround the hip (Figure 17-1). Every magnetic resonance imaging study of the hip should include a screening examination of the whole pelvis that is acquired with use of coronal inversion recovery and axial proton-density sequences. Detailed hip imaging is obtained with use of a surface coil over the hip joint, with high-resolution, cartilage-sensitive images acquired in three planes (sagittal, coronal, and oblique axial) with use of a fast-spin-echo pulse sequence and an intermediate echo time. Other alternatives include the use of magnetic resonance arthrography of the hip for the evaluation of hip pathology. Ultrasound is used most commonly to confirm the placement of injections into the trochanteric space for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Dynamic ultrasound has also been described to evaluate external coxa saltans; it provides real-time images of the sudden abnormal displacement of the iliotibial band or the gluteus maximus muscle overlying the greater trochanter as a painful snap during hip motion. In addition, sonography can identify gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tendinopathy and provide information about the severity of the disease.

Surgical technique

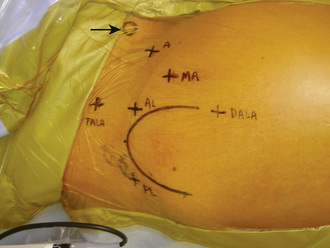

The importance of proper portal placement is critical during hip arthroscopy. For arthroscopy of the peritrochanteric space, a technique has been described that involves the use of both traditional and unique portals (Figure 17-2). The technique begins with the accurate identification of the trochanter and the marking of the arthroscopic portals. The procedure begins with routine central compartment hip arthroscopy to rule out associated intra-articular pathologies. Although intra-articular pathologies typically result in primary anterior or groin symptoms, it is also possible for these pathologies to result in primary lateral-sided hip pain. Central compartment arthroscopy is performed in all cases of peritrochanteric space endoscopy to document and treat any associated labral or chondral pathology that may coexist with the lateral-based pathology. The anterolateral portal is first established with the use of the standard Seldinger technique of a cannulated trochar over a guidewire, which is performed with the aid of fluoroscopy. To minimize trauma to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, a mid-anterior portal is then established. This portal is made slightly more lateral and distal than the traditional anterior portal. The portal is critical to get into the peritrochanteric space, because it is the initial primary viewing portal. Thus, fluoroscopy is used to assist with the optimal placement of the mid-anterior portal over the lateral prominence of the greater trochanter. Before entry into the peritrochanteric space and after the completion of the central compartment evaluation, the peripheral compartment should be entered if there is any concern about peripheral compartment pathology.

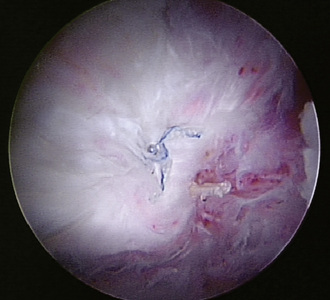

The first structure to be visualized is the gluteus maximus tendon inserting on the femur just below the vastus lateralis (Figure 17-3). This structure is a reproducible landmark that provides good orientation within the space. It is typically unnecessary to work distal to the gluteus maximus tendon, and one should avoid exploration posterior to the tendon, because the sciatic nerve lies within close proximity (i.e., 2 cm to 4 cm). The camera light source is then directed to the lateral aspect of the femur, where the longitudinal fibers of the vastus lateralis can be visualized and followed proximally to the vastus ridge. The insertion and muscle belly of the gluteus medius are located proximal to this, whereas the gluteus minimus is located more anteriorly and is mostly covered. Finally, the iliotibial band is identified with the camera looking proximally and laterally.

Gluteus Medius Repair

If there is evidence of significant gluteus medius pathology, an arthroscopic repair is performed (Figure 17-4). Occasionally, gentle distraction of the hip is needed to place the gluteus medius muscle fibers on tension to more clearly delineate proximal bursal tissue from gluteus medius muscle fibers. The 70-degree arthroscope is then placed in the proximal anterolateral accessory portal to get a more global view of the abductors, whereas the working instruments can be placed in the mid-anterior and distal anterolateral accessory portals.

The technique for fixing these tears is quite similar to that of repairing rotator cuff tears. First, a probe or grasper is used to manually reduce the tear to its anatomic position in the footprint. With a burr, the lateral facet is burred to a bleeding edge of bone in a similar fashion as is done to the greater tuberosity during a rotator cuff repair. A spinal needle is placed to find the proper angle for anchor placement, and then two metallic anchors are usually placed as a result of the hard nature of the bone in the trochanter. These anchors can be placed percutaneously to achieve the optimal angle into the bone. Fluoroscopy is again useful at this stage of the procedure to confirm the proper positioning of the anchors. A suture-passing device is then used to pass the suture through the tendon from posterior to anterior in a sequential fashion (Figure 17-5). Proper suture management is critical. Extra-long cannulas are used to help manage the suture and to tie arthroscopic knots. Finally, after all of sutures are passed, arthroscopic sliding, locking knots are created, with a knot pusher securing the medius back to its native footprint on the trochanter (Figure 17-6)

Technical Pearls

.

Results and outcomes

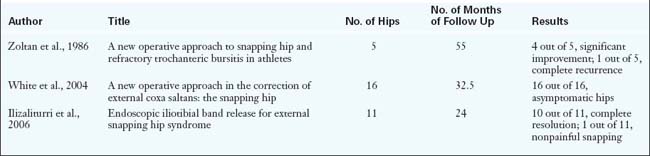

In most cases, external coxa saltans is asymptomatic, or it can be treated conservatively with rest, activity modification, stretching, corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy (Table 17-4). Zoltan and colleagues described an open surgical technique for the treatment of recalcitrant external coxa saltans that involved the excision of an ellipsoid-shaped portion of the iliotibial band overlying the greater trochanter and the removal of the trochanteric bursa. Postoperative follow up demonstrated that 80% of patients (4 out of 5) had significant improvement or relief of their symptoms, whereas 20% (1 out of 5) had no improvement. A minimally invasive technique that makes use of transverse step cuts into the fascia along a longitudinal facial incision has also been described. Fourteen of 16 hips remained asymptomatic postoperatively. The treatment of external coxa saltans with endoscopic iliotibial band release has been described by multiple authors with promising results. At an average follow up of 2 years, Ilizaliturri and colleagues reported 10 of 11 patients as having the complete resolution of pain and symptomatic snapping.

Conservative treatment in the form of one or two local corticosteroid and local anesthetic preparation injections in combination with physical therapy is the mainstay of diagnosis and treatment. This therapeutic regimen has resulted in excellent responses in 66% of cases and improvement in the remaining 33%. However, conservative therapy is not without its drawbacks. Multiple or inappropriately placed corticosteroid injections have been associated with gluteus medius injury, and open trochanteric bursectomy has been described for these refractory cases (Table 17-5). Trends toward arthroscopic treatment have also produced descriptions of endoscopic bursectomy. Baker and colleagues recently published a prospective follow up report of 25 patients treated with endoscopic bursectomy at a mean of 26.1 months postoperatively. Significant improvement was found in visual analog scale results, Harris Hip Scores, and Short Form 36 (SF-36) results. One postoperative complication occurred: a seroma that required repeat surgery. One patient had a failed arthroscopic bursectomy and subsequently underwent open bursectomy that resulted in the resolution of symptoms. Improvements in a patient’s status that are likely to be lasting are usually evident by 1 to 3 months after surgery.

The insertions of the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus at the greater trochanter and tears at this insertion have been described synonymously with tears of the rotator cuff tendons (Table 17-6). As a result of the similarities, injuries to the abductor tendons have been called rotator cuff tears of the hip. Tears were initially identified in the setting of open debridement for recalcitrant trochanteric bursitis, total hip arthroplasty, and the treatment of femoral neck fractures. Descriptions of calcific tendonitis of the hip have also included relationships with gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tears, thus further substantiating the rotator cuff similarity. Conservative treatment has included physical therapy and corticosteroid injection. Treatment has been described in an open fashion when encountered in the setting of refractory iliotibial band syndrome and total hip arthroplasty. The true incidence of gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tears is not known. A prospective study by Bunker and colleagues of 50 patients with fractures of the femoral neck revealed a 22% incidence of tears of the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus. In addition, Howell and colleagues conducted another prospective study of 176 consecutive patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis, and they identified 20% of these patients as having degenerative pathology. Recently, the arthroscopic treatment of trochanteric bursitis and calcific tendonitis of the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus has been reported by Kandemir and colleagues. Voos and colleagues reported about an arthroscopic approach that provides access for the repair of gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tendon tears. Results of this technique for 10 patients with 12 to 31 months of follow up demonstrated the full resolution of pain in 100% of patients, with 9 out of 10 patients recovering their full former strength. Moreover, an increasing understanding of the gluteus medius tendon attachment morphology may help in the development of future reparative techniques.

Annotated references and suggested readings

Allen W.C., Cope R. Coxa saltans: the snapping hip revisited. J Am Acad Orthop Surg.. 1995;3:303-308.

Baker C.L.Jr, Massie R.V., Hurt W.G., et al. Arthroscopic bursectomy for recalcitrant trochanteric bursitis. Arthroscopy.. 2007;23:827-832.

Bunker T.D., Esler C.N., Leach W.J. Rotator-cuff tear of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 1997;79:618-620.

Byrd J.W. Hip arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg.. 2006;14:433-444.

Byrd J.W. Hip arthroscopy: surgical indications. Arthroscopy.. 2006;22:1260-1262.

Choi Y.S., Lee S.M., Song B.Y., et al. Dynamic sonography of external snapping hip syndrome. J Ultrasound Med.. 2002;21:753-758.

Connell D.A., Bass C., Sykes C.A., et al. Sonographic evaluation of gluteus medius and minimus tendinopathy. Eur Radiol.. 2003;13:1339-1347.

Ege Rasmussen K.J., Fano N. Trochanteric bursitis. Treatment by corticosteroid injection. Scand J Rheumatol.. 1985;14:417-420.

Fox J.L. The role of arthroscopic bursectomy in the treatment of trochanteric bursitis. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:E34.

Govaert L.H., van der Vis H.M., Marti R.K., et al. Trochanteric reduction osteotomy as a treatment for refractory trochanteric bursitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2003;85:199-203.

Howell G.E., Biggs R.E., Bourne R.B. Prevalence of abductor mechanism tears of the hips in patients with osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty.. 2001;16:121-123.

Ilizaliturri V.M.Jr, Martinez-Escalante F.A., Chaidez P.A., et al. Endoscopic iliotibial band release for external snapping hip syndrome. Arthroscopy.. 2006;22:505-510.

Kagan A.2nd. Rotator cuff tears of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 1999:135-140.

Kandemir U., Bharam S., Philippon M.J., et al. Endoscopic treatment of calcific tendinitis of gluteus medius and minimus. Arthroscopy.. 2003;19:E4.

Kelly B.T., Williams R.J.3rd, Philippon M.J. Hip arthroscopy: current indications, treatment options, and management issues. Am J Sports Med.. 2003;31:1020-1037.

LaBan M.M., Weir S.K., Taylor R.S. “Bald trochanter” spontaneous rupture of the conjoined tendons of the gluteus medius and minimus presenting as a trochanteric bursitis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil.. 2004;83:806-809.

Robertson W.J., Gardner M.J., Barker J.U., et al. Anatomy and dimensions of the gluteus medius tendon insertion. Arthroscopy.. 2008;24:130-136.

Schapira D., Nahir M., Scharf Y. Trochanteric bursitis: a common clinical problem. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67(11):815-817.

Shindle M.K., Voos J.E., Heyworth B.E., et al. Hip arthroscopy in the athletic patient: current techniques and spectrum of disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 2007;89(suppl 3):29-43.

Tortolani P.J., Carbone J.J., Quartararo L.G. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome in patients referred to orthopedic spine specialists. Spine J.. 2002;2:251-254.

Voos J.E., Rudzki J.R., Shindle M.K., et al. Arthroscopic anatomy and surgical techniques for peritrochanteric space disorders in the hip. Arthroscopy.. 2007;23:e1-e5. 1246

Voos J.E., Shindle M.K., Pruett A., Asnis P., Kelly B.T. Endoscopic repair of gluteus medius tendon tears of the hip. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(4):743-747.

White R.A., Hughes M.S., Burd T., et al. A new operative approach in the correction of external coxa saltans: the snapping hip. Am J Sports Med.. 2004;32:1504-1508.

Wiese M., Rubenthaler F., Willburger R.E., et al. Early results of endoscopic trochanter bursectomy. Int Orthop.. 2004;28:218-221.

Zoltan D.J., Clancy W.G.Jr, Keene J.S. A new operative approach to snapping hip and refractory trochanteric bursitis in athletes. Am J Sports Med.. 1986;14:201-204.