Chapter 259 Arboviral Encephalitis in North America

Epidemiology

Eastern Equine Encephalitis

In the USA, EEE is a very low incidence disease, with a median of 8 cases occurring annually in the Atlantic and Gulf States from 1964-2007 (Fig. 259-1). Transmission occurs often in focal endemic areas of the coast of Massachusetts, the 6 southern counties of New Jersey, and northeastern Florida. In North America, the virus is maintained in freshwater swamps in a zoonotic cycle involving Culiseta melanura and birds. Various other mosquito species obtain viremic meals from birds and transmit the virus to horses and humans. Virus activity varies markedly from year to year in response to still unknown ecologic factors. Most infections in birds are silent, but infections in pheasants are often fatal, and epizootics in these species are used as sentinels for periods of increased viral activity. Cases have been recognized on Caribbean islands. The case : infection ratio is lowest in children (1 : 8) and somewhat higher in adults (1 : 29).

Western Equine Encephalitis

WEE infections occur principally in the USA and Canada west of the Mississippi River (see Fig. 259-1), mainly in rural areas where water impoundments, irrigated farmland, and naturally flooded land provide breeding sites for Culex tarsalis. The virus is transmitted in a cycle involving mosquitoes, birds, and other vertebrate hosts. Humans and horses are susceptible to encephalitis. The case : infection ratio varies by age, having been estimated at 1 : 58 in children younger than 4 yr and 1 : 1,150 in adults. Infections are most severe at the extremes of life; a third of cases occur in children younger than 1 yr. Recurrent human epidemics have been reported from the Yakima Valley in Washington State and the Central Valley of California; the largest outbreak on record resulted in 3,400 cases and occurred in Minnesota, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Montana as well as Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, Canada. Epizootics in horses precede human epidemics by several weeks. For the past 20 yr, only 3 cases of WEE have been reported, presumably reflecting successful mosquito abatement.

St. Louis Encephalitis

Cases of SLE are reported from nearly all states; the highest attack rates occur in the Gulf and central states (see Fig. 259-1). Epidemics frequently occur in urban and suburban areas; the largest, in 1975, involved 1,800 persons living in Houston, Chicago, Memphis, and Denver. Cases often cluster in areas where there is ground water or septic systems, which support mosquito breeding. The principal vectors are Culex pipiens and Culex quinquefasciatus in the central Gulf States, Culex nigripalpus in Florida, and Culex tarsalis in California. SLE virus is maintained in nature in a bird-mosquito cycle. Viral amplification occurs in bird species abundant in residential areas (e.g., sparrows, blue jays, and doves). Virus is transmitted in the late summer and early fall. The case : infection ratio may be as high as 1 : 300. Age-specific attack rates are lowest in children and highest in individuals older than 60 yr. The most recent small outbreaks were in Florida in 1990 and Louisiana in 2001. For the past 15 years there have been a mean of 18 cases annually.

West Nile Encephalitis

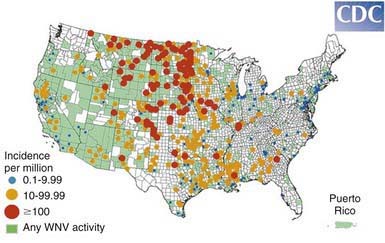

WNE virus has been implicated as the cause of sporadic summertime cases of human encephalitis and meningitis in Israel, India, Pakistan, Romania, Russia, and the USA. All American WNE viruses are genetically similar and are related to a virus recovered from a goose in Israel in 1998. WNE virus survives in a broad enzootic cycle in the USA and within 4 yr had spread to most states east of the Rocky Mountains plus California (Fig. 259-2). Every state in the continental USA plus 9 provinces in Canada have reported mosquito, bird, mammalian, or human West Nile infection. Through the end of 2008 28,813 total cases had been reported, 30-40% of which were encephalitis, with 1064 deaths. Summer/fall epidemics are common (Fig. 259-3). West Nile virus has entered the blood supply through asymptomatic viremic blood donors. Blood banks screen for West Nile virus RNA (Fig. 259-4). West Nile virus has also been transmitted to humans via the placenta, breast milk, and organ transplantation. Throughout its range, the virus is maintained in nature by transmission between mosquitoes of the Culex genus and various species of birds. In the USA, human infections are largely acquired from Culex pipiens. Horses are the non-avian vertebrates most likely to exhibit disease with WNE infection. During the 2002 transmission season, 14,000 equine cases were reported, with a mortality rate of 30%. Disease occurs predominantly in individuals >50 yr of age.

Figure 259-2 Incidence of West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease in humans—USA, 2008.

(From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: West Nile virus activity—United States, January 1-December 31, 2008 as reported to CDC’s ArboNET system.)

La Crosse/California Encephalitis

La Crosse viral infections are endemic in the USA, occurring annually from July to September, principally in the north-central and central states (See Fig. 259-1). Infections occur in peridomestic environments as the result of bites from Aedes triseriatus mosquitoes, which often breed in tree holes. The virus is maintained vertically in nature by transovarial transmission and can be spread between mosquitoes by copulation and amplified in mosquito populations by viremic infections in various vertebrate hosts. Amplifying hosts include chipmunks, squirrels, foxes, and woodchucks. A case : infection ratio of 1 : 22-300 has been surmised. La Crosse encephalitis is principally a disease of children, who may account for to 75% of cases. A mean of 100 cases have been reported annually for the past 10 years.

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of encephalitis may be aided by CT or MRI and by electroencephalography. Focal seizures or focal findings on CT or MRI or electroencephalography should suggest the possibility of herpes simplex encephalitis, which should be treated with acyclovir (Chapter 244).

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for arboviral encephalitides, although oral ribavirin may have been of benefit in a case of La Crosse encephalitis. The treatment of acute arboviral encephalitis is intensive supportive care (Chapter 62), including control of seizures (Chapter 586).

Prognosis

Armstrong PM, Andreadis TG, Anderson JF, et al. Tracking eastern equine encephalitis virus perpetuation in the northeastern United States by phylogenetic analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:291-296.

Balfour HHJr, Siem RA, Bauer H, et al. California arbovirus (La Crosse) infections I: clinical and laboratory findings in 66 children with meningoencephalitis. Pediatrics. 1973;52:680-691.

Blivich BJ. Transmission dynamics and changing epidemiology of West Nile virus. Anim Health Res Rev. 2008;9:71-86.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. West Nile virus activity—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:769-772.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Detection of West Nile virus in blood donations—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:769-772.

Civen R, Villacorte F, Robles DT, et al. West Nile infection in the pediatric population. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:75-78.

Cunha BA, Minnaganti V, Johnson DH, et al. Profound and prolonged lymphocytopenia with West Nile encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1116-1117.

Custer B, Kamel H, Kiely NE, et al. Associations between West Nile infections and symptoms reported by blood donors identified by nucleic acid screening. Transfusion. 2009;49:278-288.

Davis LE, Beckham JD, Tyler KL. North American encephalitic arboviruses. Neurol Clin. 2008;26:727-757.

Earnest MP, Goolishian HA, Calverley JR, et al. Neurologic, intellectual, and psychologic sequelae following western encephalitis: a follow-up study of 35 cases. Neurology. 1971;21:969-974.

Forrester NL, Kenney JL, Deardorff E, et al. Western equine encephalitis submergence: lack of evidence for a decline in virus virulence. Virology. 2008;380:170-172.

Haddow AD, Haddow AD. The use of oral ribavirin in the management of La Crosse viral infections. Med Hypotheses. 2009;72:190-192.

Hayes EB, Komar N, Nasci RS, et al. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile Virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1167-1173.

Hayes EB, O’Leary DR. West Nile virus infection: a pediatric perspective. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1375-1381.

Hinckley AF, O’Leary DR, Hayes EB. Transmission of West Nile virus through human breast milk seems to be rare. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e666-e671.

Komar N, Spielman A. Emergence of eastern encephalitis in Massachusetts. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;740:157-168.

Marfin AA, Bleed DM, Lofgren JP, et al. Epidemiological aspects of a St. Louis encephalitis epidemic in Jefferson County, Arkansas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:30-37.

Minke JM, Audonnet JC, Fischer L. Equine viral vaccines: the past, present and future. Vet Res. 2004;35:425-443.

Reimann CA, Hayes EB, DiGuiseppi C, et al. Epidemiology of neuroinvasive arboviral diseases in the United States, 1999–2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:974-979.

Sejvar JJ, Hadded MB, Tierney BC, et al. Neurologic manifestations and outcome of West Nile virus infection. JAMA. 2003;290:511-515.

Solomon T. Flavivirus encephalitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:370-378.

Spruance SL, Bailey A. Colorado tick fever: a review of 115 laboratory confirmed cases. Arch Intern Med. 1973;131:288-293.

Stramer SL, Fang CT, Foster GA, et al. West Nile virus among blood donors in the United States, 2003 and 2004. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:451-459.