191 Approach to the Adult Rash

• Rashes are a common reason for a visit to the emergency department. Some rashes are simple and straightforward. However, others represent the initial complaint of a patient with a life-threatening disease.

• Fever with a rash is key to recognizing some of the more dangerous conditions.

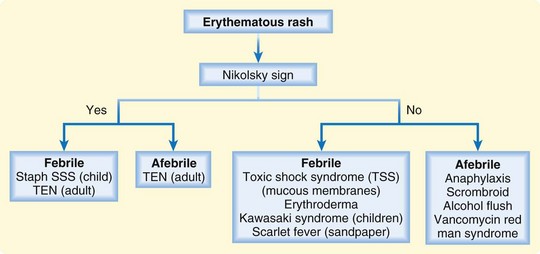

• The key for differentiating a diffusely erythematous rash includes the presence or absence of the Nikolsky sign.

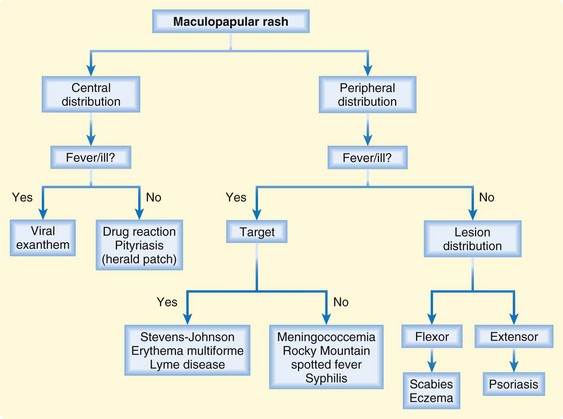

• Key factors for differentiating a maculopapular rash include its distribution and target lesions.

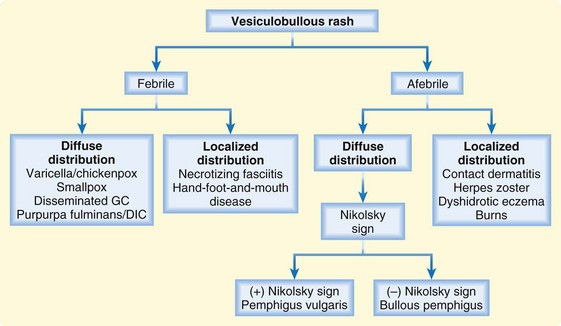

• A vesiculobullous rash is also differentiated by distribution; a localized or diffuse distribution helps narrow the differential diagnosis.

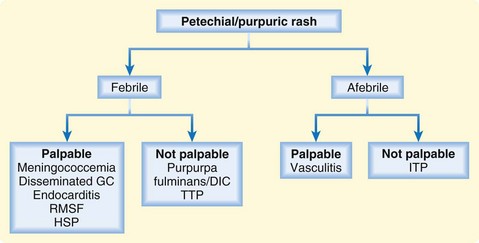

• Petechial/purpuric rashes are differentiated by the presence or absence of palpable lesions.

• Petechiae do not blanch with pressure.

• Palpable purpura occurs in vasculitic diseases secondary to inflammation or infection.

• Nonpalpable purpura is characteristic of thrombocytopenic conditions.

• Bullous rash with mucosal involvement is worrisome, and steroid therapy may be warranted.

• A careful history and physical examination are crucial for narrowing the differential diagnosis of an unknown rash.

Epidemiology

Evaluation of rashes ranks highly among the top 20 reasons for visits to the emergency department.

A well-reasoned algorithmic approach to the evaluation of rashes might aid the emergency medicine specialist in identifying the most common and potentially lethal rash syndromes. Although an exhaustive review of all potential fungal, parasitic, and viral causes of rash is beyond the scope of this chapter, the algorithms presented will equip physicians to quickly recognize the most common and critical rashes. Pediatric rashes are discussed in detail in Chapter 18. Additionally, the most life-threatening rashes are discussed in more detail in Chapter 192.

Pathophysiology

A rash is a skin eruption that has a defined morphology and location. The morphology of the rash is usually distinct and related to the pathophysiologic dysfunction of the skin. Most severe rashes begin as exanthems (from the Greek exanthema, which means “breaking out,” and anthos, which means “flowering”). These rashes subsequently take on a particular morphology, characteristic lesions, or distribution. Table 191.1 delineates the most common terms used for skin lesions. Understanding these terms helps one better document progression of disease and facilitates communication with consulting physicians.

| TERM | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Lesion | Single small diseased area |

| Macule | Circumscribed area of change without elevation |

| Rash | Skin eruption that is more extensive than a single lesion |

| Papule | Solid raised lesion < 1 cm |

| Nodule | Solid raised lesion > 1 cm |

| Plaque | Raised confluence of papules > 1 cm |

| Pustule | Fluid-filled area containing purulence |

| Vesicle | Fluid-filled area < 1 cm containing clear fluid |

| Bullae | Fluid-filled area > 1 cm |

| Petechiae | Pinpoint flat round spots < 3 mm caused by intradermal bleeding that do not blanch |

| Purpura | Hemorrhagic area > 3 mm that does not blanch |

| Exanthem | Rash outside the body (skin) |

| Enanthem | Rash inside the body (mucous membranes) |

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Eliciting the initial distribution and progression of a rash is essential. Additionally, the involvement of palms, soles, and mucous membrane is of key importance. It should be kept in mind that dysphasia, as well as eye or genital irritation, may be a manifestation of as mucosal involvement and is often the initial symptom of several life-threatening conditions. The rash’s rapidity of progression is also an essential in diagnosis. Box 191.1 categorizes these important findings.

Box 191.1 Distribution and Progression of a Rash

Specific Signs

Two signs are important in the evaluation of these rashes: the Nikolsky sign and the Asboe-Hansen sign. A positive Nikolsky sign (Fig. 191.1) is noted when slight rubbing of the skin results in exfoliation of the outermost layer with lateral extension of the erosion into the intact skin. The area of denuded skin is pink and tender. The Asboe-Hansen sign (indirect Nikolsky sign or Nikolsky II sign) is extension of a blister into normal skin with the application of light pressure on the top of the blister. All patients with tender, blistering, or sloughing skin should be evaluated serially for these important signs.

Differential Diagnoses and Medical Decision Making

The Algorithmic Approach

Erythematous Rashes

These rashes are characterized by diffuse redness of the skin as a result of capillary congestion. Erythematous rashes are differentiated by the presence or absence of fever and the Nikolsky sign (Fig. 191.2).1 If a Nikolsky sign is present, the diagnosis is narrowed substantially, usually to TEN in adults and to staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), generally in infants and young children. If fever is present without a Nikolsky sign, the differential diagnosis includes Kawasaki disease, scarlet fever, erythroderma, and toxic shock syndrome (TSS). Patients with an erythematous rash but without a fever or Nikolsky sign may be having an anaphylactic reaction or a reaction to vancomycin, scombroid, or alcohol exposure. Please refer to Chapter 18 for review of SSSS, Kawasaki disease, and scarlet fever. Refer to Chapter 192 for review of TEN, TSS, and erythroderma.

Maculopapular Rashes

The term maculopapule is a portmanteau of macule and papule. Maculopapular rashes are differentiated by the distribution of the rash and systemic toxicity (Fig. 191.3). Patients with centrally distributed rashes who appear toxic and febrile have a wide differential diagnosis; however, it is paramount that patients living in endemic areas be assessed for Lyme disease. Those with centrally distributed rashes but no signs of toxicity usually have either a drug reaction or pityriasis rosea. Patients with peripherally distributed rashes have a broader differential diagnosis that is dependent on systemic toxicity, the presence or absence of target lesions, and whether the rash is located on the flexor or extensor surfaces. Target lesions (Fig. 191.4) are pathognomonic for SJS or erythema multiforme (EM). The target lesion of Lyme disease is usually a single large bull’s eye that measures at least 5 cm in diameter (erythema migrans). Patients with peripheral lesions and systemic toxicity but without target lesions require emergency evaluation for meningococcemia, RMSF, and syphilis. Nontoxic patients with a peripherally distributed rash and no target lesions require further assessment for flexor involvement (scabies or eczema) or extensor involvement (psoriasis). Please refer to Table 191.2 for review of EM minor and major. See Chapter 18 for review of viral exanthems. Please refer to Chapter 192 for review of Lyme disease, meningococcemia, RMSF, SJS, and syphilis.

Fig. 191.3 Algorithm for maculopapular rashes.

(From Murphy-Lavoie H, LeGros TL. Emergent diagnosis of the unknown rash: an algorithmic approach. Emerg Med 2010;42[3]:6-17.)

| Causes | Possibly autoimmune | |

| Unknown in 50% | ||

| Exposures | Infections: herpes simplex, Mycoplasma, fungi | |

| Drug exposures: sulfa and other antibiotics, anticonvulsants | ||

| Classification | Erythema multiforme minor | Erythema multiforme major |

| Description | Mild, self-limited rash | Severe, life-threatening disease with significant mucous membrane involvement2 |

| Prodromal symptoms | No prodromal symptoms | Mild upper respiratory infection with moderate fever |

| Cough, sore throat, chest pain | ||

| Vomiting and diarrhea | ||

| Rash appears in 1-2 wk | ||

| Rash characteristics | Symmetric extremity lesions that develop into target lesions | Begins as a maculopapular rash that evolves into target lesions; rapidly progressive with centripetal spread |

| Distribution | Lower extremities | Palms, soles, dorsa of hands, face, and extensor surfaces |

| Mucous membrane involvement | None | Significant mucous membrane involvement |

| Eye involvement (10%); often bilateral, purulent conjunctivitis | ||

| Pruritic | Yes | No |

| Diagnosis | Confirmed with biopsy | Confirmed with biopsy |

| Treatment | ||

Petechial/Purpuric Rashes

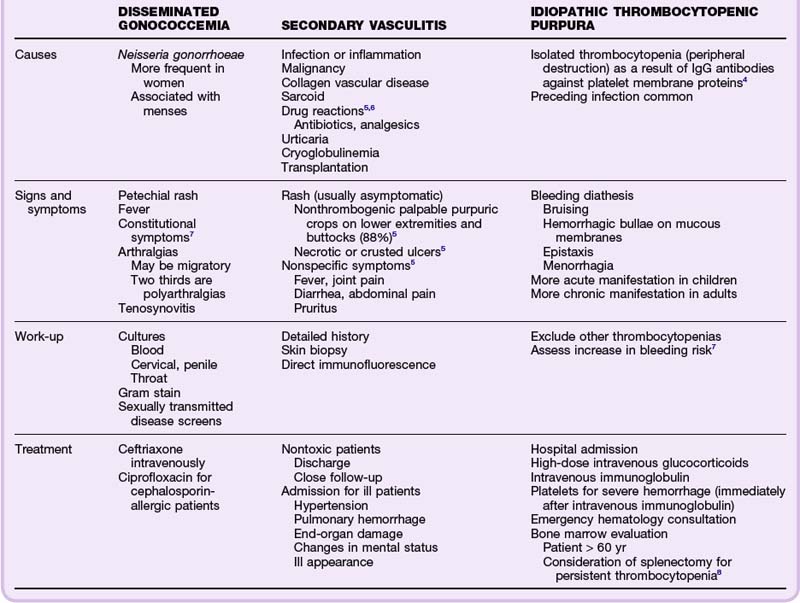

These rashes can be especially challenging and are associated with devastating differential diagnoses; however, an algorithmic approach can help the physician narrow the diagnosis with confidence (Fig. 191.5). By definition, petechiae do not blanche with pressure; additionally, remembering the cause of palpable versus nonpalpable lesions is paramount. Palpable (raised) purpura occurs in vasculitic diseases secondary to inflammation or infection. Nonpalpable purpura (flat, subcutaneous hemorrhages) are seen with thrombocytopenic conditions. Patients with petechial/purpuric rashes and fever or toxicity require emergency evaluation. If the lesions are palpable, the differential diagnosis includes meningococcemia, disseminated gonococcal disease, endocarditis, RMSF, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). Those with petechial/purpuric rashes and fever or toxicity but without palpable lesions may have purpura fulminans, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), or TTP. If the patient is afebrile and has a petechial or purpuric rash, the diagnosis may be far simpler and less ominous. Nontoxic patients with palpable lesions may have a vasculitis; those with nonpalpable lesions may have idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). A detailed history may elucidate the cause of a vasculitis by identifying a key drug use history, recent illness, or an underlying symptom characteristic of the triggering disease.5 In patients with ITP, it is important to exclude other causes of thrombocytopenia, including HIV infection, hepatitis, autoimmune disease, liver or renal disease, cancer, infection, pregnancy, alcohol use, and exposure to heparin or other inciting drugs or agents. Patient with ITP also require a full assessment of their risk for complications because of their thrombocytopenic condition, including age older than 60 years, engagement in athletic sport activities, peptic ulcer disease, menorrhagia, and intracranial hemorrhage.4 Please refer to Table 191.3 for review of disseminated gonococcemia, secondary vasculitis, and ITP. Box 191.2 lists a vasculitis classification scheme, and these conditions are discussed in more detail in Chapter 110. Please refer to Chapter 18 for review of HSP and Chapter 192 for review of meningococcemia, endocarditis, RMSF, TTP, and purpura fulminans/DIC.

Fig. 191.5 Algorithm for petechial/purpuric rashes.

(From Murphy-Lavoie H, LeGros TL. Emergent diagnosis of the unknown rash: an algorithmic approach. Emerg Med 2010;42[3]:6-17.)

Vesiculobullous Rashes

Vesiculobullous rashes provoke significant angst in many physicians (Fig. 191.6). However, the differential diagnosis can be greatly simplified by categorizing patients with these rashes as febrile or afebrile and noting whether the distribution of the rash is diffuse or localized. Patients with a diffuse vesiculobullous rash and a fever may have varicella or a more devastating illness such as smallpox, disseminated gonococcal disease, or purpura fulminans/DIC. Necrotizing fasciitis and hand-foot-and-mouth disease are characterized by localized lesions and fever. In afebrile patients with a diffuse vesiculobullous rash, the differential diagnosis includes bullous pemphigus (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris (PV). One of the distinguishing features is based on the Nikolsky sign. A positive Nikolsky sign is seen with PV but is absent in BP. These entities are regularly confused, and it is essential to differentiate them urgently. It is important to remember that both BP and PV have strong associations and known triggers. For those with BP, the list of drug triggers includes furosemide, ibuprofen, captopril (or other thiol-containing compounds), penicillamine, and antibiotics. Patients with PV have similar drug triggers (with the addition of rifampin). Please refer to Table 191.4 for additional associations for PV and BP. The differential diagnosis is simpler and less of an emergency in a patient who is afebrile with a localized vesiculobullous rash; contact dermatitis, herpes zoster, dyshidrotic eczema, and burns are included in the differential diagnosis. Please refer to Table 191.4 for a discussion of PV and BP. Refer to Chapters 18 and 192 for review of varicella and Chapter 192 for review of smallpox, purpura fulminans/DIC, and necrotizing fasciitis.

| PEMPHIGUS VULGARIS | BULLOUS PEMPHIGUS | |

|---|---|---|

| Causes |

Treatment

Erythematous Rashes

Febrile Patients with a Positive Nikolsky Sign

These patients are systemically ill and require intensive treatment. Patients with SSSS usually require hospitalization for fluid and electrolyte management and supportive wound and skin care. Young, well-appearing patients with SSSS and minimal skin sloughing may be managed as outpatients. However, adult patients with SSSS have a 60% mortality rate and require much closer monitoring. Antibiotics are usually recommended, but is it unclear whether they measurably alter the course of the disease. Please refer to Chapters 18 and 192 for further review. Patients with TEN require immediate discontinuation of the offending agent, wound care, eye care, fluid and electrolyte resuscitation, and admission to either an intensive care unit (ICU) or burn unit. Intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) may be helpful, but it has yet to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this use. Most physicians recommend against steroid use. It is important to avoid sulfadiazine on these wounds because sulfa is a common offending agent.

Febrile Patients Without a Positive Nikolsky Sign

These patients are systemically ill and require intensive treatment. Patients with TSS require immediate removal of the infective material, intravenous antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, ICU admission, and consideration of the use of IVIG. Erythroderma is a devastating and overwhelming disease. All patients require admission, fluid and electrolyte monitoring, skin care, antihistamines, prevention of secondary infection, treatment of the underlying cause, and topical steroids. Systemic steroids are controversial. Recovery is long and recurrences are common. Patients with Kawasaki syndrome require high-dose aspirin immediately, hospitalization, and IVIG. Those with scarlet fever require penicillin to prevent local suppurative complications and acute rheumatic fever. Please refer to Chapter 18 for review of scarlet fever. Refer to Chapter 192 for review of erythroderma. Refer to Chapters 18 and 192 for review of Kawasaki disease and TSS.

Maculopapular Rashes

Central Maculopapular Rashes in Febrile or Ill-Appearing Patients

These patients usually have viral exanthems. They are typically ill appearing with fever but are not moribund. Most patients respond to supportive care. Please refer to Chapter 18 for a discussion of pediatric exanthems.

Peripheral Maculopapular Rashes in Febrile or Ill-Appearing Patients with Target Lesions

These patients may have EM major (refer to Table 191.2 for review). SJS and Lyme disease are also in the differential diagnosis. Treatment of SJS involves discontinuation of the offending agent, optimization of fluid and electrolyte balance, meticulous wound care, and ICU admission. For patients with Lyme disease, doxycycline is first-line treatment in nonpregnant adults. Children are treated with amoxicillin. Refer to Chapter 192 for further review of SJS and Lyme disease.

Peripheral Maculopapular Rashes in Febrile or Ill-Appearing Patients Without Target Lesions

These patients may have meningococcemia, RMSF, or syphilis. Patients with meningococcemia require intravenous ceftriaxone, with vancomycin added in cases of diagnostic uncertainty or to cover resistant streptococcal meningitis. Dexamethasone reduces neurologic sequelae if administered early and before antibiotics if possible. These patients also require admission and continuous surveillance for end-organ damage and complications. RMSF is always in the differential diagnosis in patients with these rashes or in those in whom meningococcemia is suspected. With any diagnostic uncertainty, one should treat for both illnesses. Doxycycline is the drug of choice in all nonpregnant patients with RMSF, even children. Pregnant patients may be treated with chloramphenicol, although doxycycline should also be considered because it is simply more effective. Secondary syphilis is also a diagnostic possibility in these patients and should be treated with intramuscular penicillin G in all patients. Benzathine penicillin should not be used because it does not penetrate cerebrospinal fluid. Pregnant patients allergic to penicillin should undergo desensitization. Nonpregnant, penicillin-allergic patients may be treated with doxycycline. Refer to Chapter 192 for further information on meningococcemia, RMSF, and syphilis.

Petechial/Purpuric Rashes

Palpable Petechial/Purpuric Rashes in Febrile Patients

These patients have wide differential diagnoses with high morbidity and mortality. Meningococcemia and RMSF were discussed in the section related to the treatment of maculopapular rashes. Treatment of disseminated gonococcemia is reviewed in Table 191.3. Patients with endocarditis require early recognition, intensive therapy, broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus (with subsequent guidance by blood cultures), and cardiology consultation. See Chapter 192 for further information on endocarditis. HSP is a small vessel vasculitis that is usually self-limited, and treatment is supportive. NSAIDs are used to reduce joint and soft tissue pain. Patients with significant bleeding, intussusception, and renal failure require admission for HSP. Please refer to Chapter 192 for review of endocarditis and Chapter 18 for review of HSP.

Nonpalpable Petechial/Purpuric Rashes in Febrile Patients

Purpura fulminans and DIC are acutely life-threatening disorders that require emergency hematology consultation and ICU admission. First-line therapy is treatment of the underlying cause. Folate, vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, platelets, and red blood cell transfusions are given as needed. Heparin is also used for associated thrombi. These patients are very ill, and use of these therapies is best done in consultation with the ICU team and a hematologist. TTP is a devastating disease with greater than 90% mortality if not treated properly. Treatment includes emergency hematology consultation, treatment of the underlying cause, fresh frozen plasma (as a temporizing measure), plasmapheresis, and ICU admission. It is important to avoid platelet administration because it will precipitate more thrombus formation. Exchange transfusions can reduce mortality to 10%, and facilities without these capabilities should consider early transfer. Please refer to Chapter 192 for further review of purpura fulminans/DIC and TTP.

Vesiculobullous Rashes

Febrile Patients with a Diffuse Rash

These patients may have varicella, smallpox, disseminated gonococcemia, or purpura fulminans/DIC. Varicella is a childhood viral exanthem (chickenpox) that is intensely pruritic. Treatment is supportive and consists of wet dressings, soothing baths, calamine lotion, surveillance for secondary infection, and antihistamines. The role of acyclovir in healthy children is unclear. Immunocompromised patients are at risk for significant complications. Maternal infection in the first trimester may result in devastating congenital varicella syndrome, whereas perinatal maternal infection predisposes to disseminated neonatal herpes. Smallpox is a dreaded variola infection against which 50% of the U.S. population has not been vaccinated. Care is supportive, and all personnel with smallpox exposure require quarantine and vaccination. The mortality rate is 30% in those who are unvaccinated. Treatment of disseminated gonococcemia is reviewed in Table 191.3. Treatment of purpura fulminans/DIC was reviewed with petechial/purpuric rashes. Please refer to Chapter 18 for review of varicella and Chapter 192 for review of smallpox and purpura fulminans/DIC.

Febrile Patients with a Localized Rash

Necrotizing fasciitis is in the differential diagnosis for these patients. It is an acutely toxic bacterial infection with very high mortality. Treatment consists of prompt surgical débridement, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is a highly contagious viral illness that requires symptomatic care for the painful oral ulcers. Complications are rare; however, infection during the first trimester of pregnancy may result in spontaneous abortion. Please refer to Chapter 192 for review of necrotizing fasciitis and Chapter 18 for review of hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

Afebrile Patients with a Diffuse Rash

These patients have either BP or PV. Both these diseases and their treatments are reviewed in Table 191.4.

Follow-Up and Patient Education

Carr DR, Houshmand E, Heffernan MP. Approach to the acute, generalized, blistering patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:139–146.

Mukasa Y, Craven N. Management of toxic epidermal necrolysis and related syndromes. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:60–65.

Murphy-Lavoie H, LeGros T. Emergent diagnosis of the unknown rash, the algorithmic approach. Emerg Med. 2010;42(3):6–17.

Nguyen T, Freedman J. Dermatologic emergencies: diagnosing and managing life-threatening rashes. Emerg Med Pract. 2002;4:1–28.

Rothe MJ, Bernstein ML, Grant-Kels JM. Life-threatening erythroderma: diagnosing and treating the “red man.”. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:206–217.

1 Murphy-Lavoie H, LeGros TL. Emergent diagnosis of the unknown rash: an algorithmic approach. Emerg Med. 2010;42(3):6–17.

2 Mukasa Y, Craven N. Management of toxic epidermal necrolysis and related syndromes. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:60–65.

3 Nguyen T, Freedman J. Dermatologic emergencies: diagnosing and managing life-threatening rashes. Emerg Med Pract. 2002;4(9):1–28.

4 Cines DB, Blanchette VS. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:995–1008.

5 Ross JDC. Systemic gonococcal infection. Genitourin Med. 1996;72:404–407.

6 Gupta S, Handa S, Kanwar A, et al. Cutaneous vasculitides: clinico-pathological correlation. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;74:356–362.

7 Ekenstam E, Callen JP. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis—clinical and laboratory features of 82 patients seen in private practice. Arch Dermatol. 2006;120:484–489.

8 Marieke Schoonen W, Kucera G, Coalson J, et al. Epidemiology of immune thrombocytopenic purpura in the General Practice Research Database. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:235–244.

9 Carr DR, Houshmand E, Heffernan MP. Approach to the acute, generalized, blistering patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:139–146.

10 Chan L. Bullous pemphigoid. eMedicine. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1062391-overview, 2009. Updated November 20