Chapter 7 Approach to Anemia in the Adult and Child

Table 7-1 Usefulness of the Reticulocyte Count in the Diagnosis of Anemia*

| Diagnosis | Value |

|---|---|

| Hypoproliferative Anemias | Absolute Reticulocyte Count <75,000/µL |

| Anemia of chronic disease | |

| Anemia of renal disease | |

| Congenital dyserythropoietic anemias | |

| Effects of drugs or toxins | |

| Endocrine anemias | |

| Iron deficiency | |

| BM replacement | |

| Maturation Abnormalities | Absolute Reticulocyte Count <75,000/µL |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | |

| Folate deficiency | |

| Sideroblastic anemia | |

| Appropriate Response to Blood Loss or Nutritional Supplementation | Absolute Reticulocyte Count ≥100,000/µL |

| Hemolytic Anemias | Absolute Reticulocyte Count ≥100,000/µL |

| Hemoglobinopathies | |

| Immune hemolytic anemias | |

| Infectious causes of hemolysis | |

| Membrane abnormalities | |

| Metabolic abnormalities | |

| Mechanical hemolysis |

BM, Bone marrow.

*Note that reticulocyte counts in the range of 75,000 to 100,000/µL can sometimes be associated with appropriate response to blood loss or hemolytic anemia.

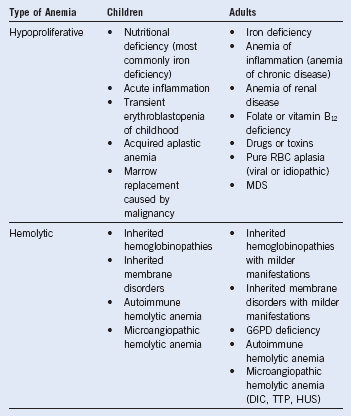

Table 7-2 Comparison of the More Common Causes of Anemia in Children and Adult

DIC, Disseminated intravascular coagulation; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; RBC, red blood cell; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

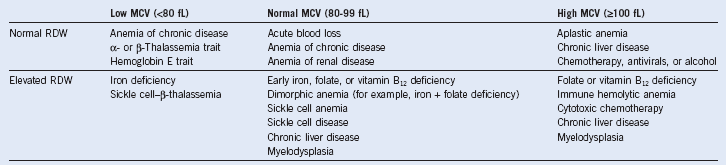

Table 7-3 Usefulness of the Mean Corpuscular Value and Red Blood Cell Distribution Width in the Diagnosis of Anemia

MCW, Mean corpuscular value; RDW, red blood cell distribution width.

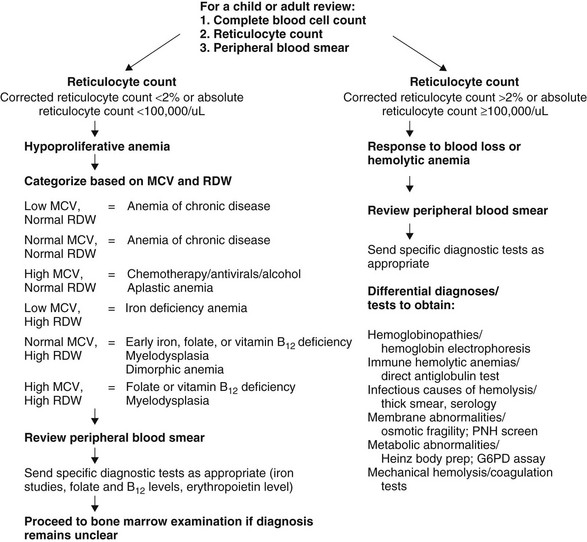

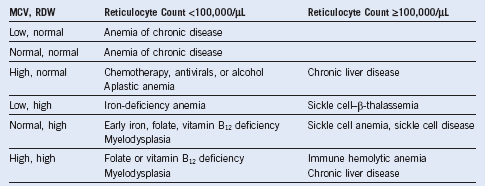

Table 7-4 Combining the Reticulocyte Count and Red Blood Cell Parameters for Diagnosis

MCV, Mean corpuscular volume; RDW, red blood cell distribution width.

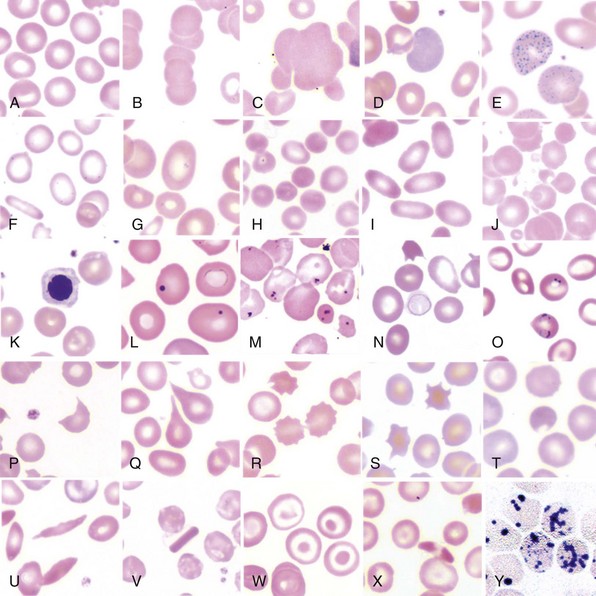

Table 7-5 Features of the Peripheral Blood Smear

| Red Blood Cell Morphology | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Polychromasia | Large, bluish RBCs lacking normal central pallor on peripheral blood smear; bluish stain is the result of residual ribonucleic acid | Rapid production and release of RBCs from BM; elevated reticulocyte count; most commonly seen in hemolytic anemia |

| Basophilic stippling | Many small bluish dots in portion of erythrocytes; comes from staining of clustered polyribosomes in young circulating RBCs | Seen in a variety of erythropoietic disorders, including acquired and congenital hemolytic anemias and occasionally in lead poisoning (lead inhibits pyrimidine 5’-nucleotidase, which normally digests the residual RNA) |

| Pappenheimer bodies | Several grayish, irregularly shaped inclusions in a portion of erythrocytes visible on peripheral smear; composed of aggregates of ribosomes, ferritin, and mitochondria | Erythropoietic malfunction in congenital anemias such as hemoglobinopathies, particularly with splenic hypofunction or acquired anemias such as megaloblastic anemia |

| Heinz bodies | Several grayish, round inclusions visible after supravital staining with methyl crystal violet of the peripheral blood smear, often in the context of bite cells; represent aggregates of denatured hemoglobin | Indicative of oxidative injury to the erythrocyte, such as occurs in G6PD deficiency, or less commonly of unstable hemoglobins |

| Howell-Jolly bodies | Usually one or at most a few purplish inclusions in the erythrocyte visible on the routine peripheral blood smear; represent residual fragments of nuclei containing chromatin | Associated with states of splenic hypofunction or after splenectomy |

| Schistocytes | RBCs that are fragmented into a variety of shapes and sizes, including helmet-shaped cells; indicative of shearing of the erythrocyte within the circulation | Associated with microangiopathic hemolytic anemias, including DIC, TTP, or HUS, as well as other mechanical causes of hemolysis, such as prosthetic valves |

| Spherocytes | RBCs that have lost their central pallor and appear spherical; indicative of loss of cytoskeletal integrity from internal or external causes | Associated with hereditary spherocytosis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; may also be observed in addition to schistocytes in the presence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia |

| Teardrop cells | Pear-shaped erythrocytes visible on peripheral blood smear; indicative of mechanical stress on the RBC during release from the BM or passage through the spleen | Seen in a variety of conditions, including congenital anemias such as thalassemia and acquired disorders such as megaloblastic anemia; may also suggest a more ominous process such as myelophthisis (BM replacement) |

| Burr cells (echinocytes) | RBCs that have smooth undulations present on the surface circumferentially; pathogenesis unknown | Indicative of uremia when present on a properly made peripheral blood smear |

| Spur cells (acanthocytes) | RBCs that have spiny points present on the surface circumferentially; reflective of abnormal lipid composition of RBC membrane | Most commonly indicative of liver disease when present in significant numbers; also seen in abetalipoproteinemia and in RBCs lacking the Kell blood group antigen |

BM, Bone marrow; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; RBC, red blood cell; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Systematic Approach to the Diagnosis of Anemia

Special stains of the peripheral blood smear can be helpful in elucidating the cause of anemia. If there is significant nuclear debris present, the reticulocyte count obtained by automated methods can be inaccurate. In such cases, manual counting after staining with new methylene blue, which stains residual RNA in reticulocytes, permits accurate enumeration. If bite cells are detected on peripheral smear, supravital staining with methyl crystal violet can reveal Heinz bodies. These are aggregates of denatured hemoglobin reflecting an oxidative insult, most commonly caused by glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency or, less frequently, by the presence of an unstable hemoglobin (see Fig. 7-2, H).