65 Aortic Dissection

• Aortic dissection is deadly and difficult to diagnose. It is suspected less than half the time at initial evaluation.

• Ninety percent of patients with aortic dissection have sudden, severe, or unrelenting pain in the chest or upper part of the back, or in both areas.

• When a patient has chest pain with a pulse deficit or any acute neurologic deficit, aortic dissection is the most likely diagnosis.

• D-dimer is a sensitive biomarker for ruling out dissection. Computed tomographic angiography is the study of choice for making the diagnosis.

• Systolic blood pressure in patients with aortic dissection should be maintained at less than 120 mm Hg regardless of the patient’s baseline blood pressure unless symptoms or signs of organ malperfusion are present. Beta-blockers are the first-line antihypertensives.

Epidemiology

A patient in the emergency department (ED) whose proximal aorta has dissected has about a 2% chance of dying every hour during the first 12 hours and almost a 50% chance of dying within 48 hours without surgical treatment.1,2 Unfortunately, this disease is often difficult to diagnose. A study involving three academic EDs found that the diagnosis was suspected during the initial encounter in only 43% of cases.3

The incidence is 3 per 100,000 people per year.4,5 A typical large urban ED sees several cases per year.3 About 1 in 350 patients evaluated in an ED for chest pain has aortic dissection.4–6

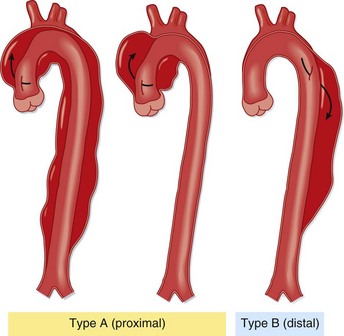

Sixty percent of aortic dissections involve the ascending aorta, either alone or with other parts of the aorta; they are referred to as type A in the now standard Stanford classification. The 40% that do not involve the ascending aorta are Stanford type B (Fig. 65.1). This distinction has important prognostic and therapeutic implications.

The Young Patient

About 7% of patients with aortic dissection are young (<40 years) and usually have no history of hypertension or other known medical problems.7 These patients nearly always have occult structural cardiovascular disease.

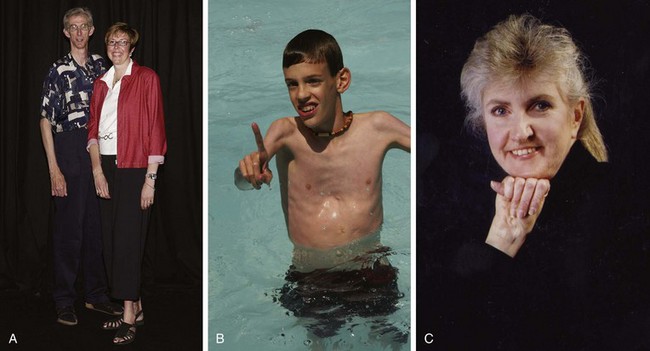

The most important structural vascular disease is Marfan syndrome, which has a prevalence of 1 in 10,000 and occurs in all races. Marfan syndrome accounts for half of aortic dissections in patients younger than 40 years.7 It is caused by an autosomal dominant mutation in the gene for a type of fibrillin, a protein that makes up part of the elastic fibers in connective tissue of the aorta, lens, and periosteum. Patients are typically tall with long digits, scoliosis, pectus excavatum, and visual problems because of lens dislocation (Fig. 65.2, A to C). Most important, however, thoracic aneurysms invariably develop early in life, usually in the ascending aorta. If their aneurysms are not repaired, most patients will die of aortic dissection or rupture.

Other young patients without a history of severe hypertension who are nevertheless at risk for dissection are those with bicuspid aortic valves and those experiencing acute insults such as cocaine use and trauma. A family history of aortic aneurysms and dissection, beyond syndromes usually associated with aortic pathology, is a newly recognized risk factor seen in 10% to 20% of patients with dissection.8

Pathophysiology

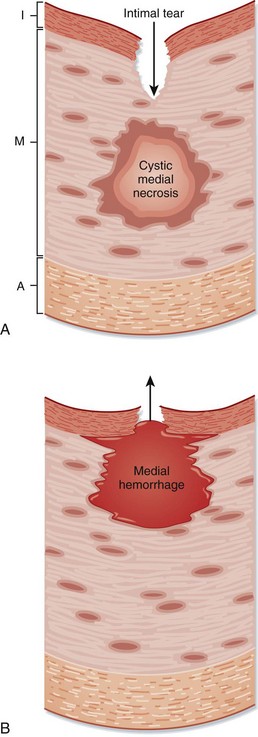

The aorta dissects by two possible mechanisms (Fig. 65.3). The classic mechanism is an intimal tear, which is generally transverse and extends through the very thin tunica intima into the tunica media. Under pulsatile force, blood enters a layer of the media and dissects longitudinally and usually in a distal direction. The other major mechanism is rupture of the vasa vasorum, usually of a penetrating branch within the tunica media, with consequent bleeding into the media. Progression then occurs in the same fashion, either with or without secondary tearing through the intima into the aortic lumen. The aorta generally tears near tethering points, where the vessel undergoes the greatest flexion stress during cardiac contractions. Thus the most common location for initiation of dissection is the first few centimeters of the ascending aorta, the next most common being the origin of the descending aorta just distal to the left subclavian artery.

Fig. 65.3 Two mechanisms of aortic dissection.

A, Intimal tear. B, Rupture of the vasa vasorum. A, Adventitia; I, intima; M, media.

(From Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, et al, editors. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.)

Those who suffer dissection are predisposed to it by a weakened aorta, specifically, degeneration of the tunica media, or suffer a hemodynamic or traumatic insult, or both (Table 65.1).7–9 Medial degeneration can be secondary to chronic hypertension, hereditary diseases of elastin (Marfan syndrome) or collagen (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), hereditary structural abnormalities (bicuspid aortic valve and aortic coarctation), chronic inflammation, and aneurysm of any cause, which increases wall tension according to Laplace’s law.

| RISK FACTORS | PREVALENCE (%) |

|---|---|

| Common Factors | |

| Hypertension | 70 |

| Family history of aortic dissection or aneurysm | 10-20 |

| Aortic aneurysm (known) | 13 |

| Previous aortic dissection | 5 |

| Marfan syndrome | 5 (50% in patients < 40 yr) |

| Aortic valve disease: atrioventricular replacement, bicuspid aortic valve | 9 |

| Iatrogenic: cardiac surgery, cardiac catheterization | 4 |

| Uncommon Factors | |

| Cocaine or methamphetamine use | |

| Pregnancy | |

| Weight lifting | |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome—vascular type | |

| Coarctation of the aorta | |

| Chronic inflammation | |

| Giant cell (temporal) arteritis | |

| Takayasu arteritis | |

| Tertiary syphilis | |

| Trauma | |

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Dissection of the aorta is usually extremely painful, so acute pain is a chief complaint in nearly 95% of cases (Table 65.2).7,10–14 Aortic pain is sudden and maximal at onset, with its intensity often proportional to the length of dissection. The location of pain is midline and, classically, correlates with the location of dissection: dissection of the ascending aorta results in chest pain, dissection of the arch results in neck or jaw pain, and dissection of the descending aorta results in back and sometimes abdominal pain. Thus the pain may migrate as the dissection propagates. However, there is considerable variability in symptoms and major overlapping of symptoms in type A and type B dissections.3,9

Table 65.2 Symptoms, Signs, and Findings in Patients with Aortic Dissection

| PREVALENCE (%) | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Pain | |

| Any | 94 |

| Sudden | 90 |

| Severe | 90 |

| Migrating | 25 |

| Tearing/ripping | ≈35 |

| Chest pain | 67 |

| Back pain | 50 |

| Abdominal pain | 25 |

| Syncope | 12 |

| Physical Findings | |

| High blood pressure | 50 |

| Hypotension or shock | 15 |

| Diastolic murmur | 33 |

| Pulse deficit | 30 |

| Focal neurologic deficit | 15 |

| Study Results | |

| Chest radiograph | |

| Wide mediastinum | ≈60 |

| Abnormal aortic contour | ≈60 |

| Normal | 15 |

| Electrocardiography | |

| Myocardial infarction (ST elevation or new Q waves) | 5 |

| Myocardial ischemia (ST depression or T-wave inversion) | 15 |

Data from references 7, 10–14.

The patient appears to be in obvious pain and often has elevated blood pressure (see Table 65.2). On cardiac examination the emergency physician (EP) may hear a fourth heart sound (S4) because of left ventricular hypertrophy. The patient must be examined for two life-threatening complications of type A dissection with retrograde propagation: aortic regurgitation and cardiac tamponade. Aortic regurgitation occurs audibly in a third of cases and is manifested as a decrescendo early diastolic murmur, best heard at the left lower sternal border with the patient sitting up, leaning forward, and holding breath at end-expiration; peripheral pulses can be bounding if the pulse pressure is wide. Cardiac tamponade may be manifested as distant heart sounds, but more often tachycardia and jugular venous distention occur and are followed by hypotension; the pulsus paradoxus should be 10 mm Hg higher, and bedside ultrasound will reveal a pericardial effusion.

Peripheral pulses should also be examined. If the false lumen is occluding one of the subclavian arteries, a focal, palpably weak pulse is usually present, a finding specific for aortic dissection.11 Blood pressure should be measured in both arms—a difference of 20 mm Hg or greater between extremities should alert the EP to the possibility of subclavian occlusion. It must be remembered, though, that nearly 20% of hypertensive patients have a blood pressure differential of at least 10 mm Hg between extremities.15 Lower extremity pulses should also be evaluated because frank ischemia of the lower extremities occurs in nearly 10% of cases of aortic dissection.13

A thorough neurologic examination should be performed. Fifteen percent of patients with aortic dissection have a focal neurologic deficit, and in the setting of severe acute chest or abdominal pain, this finding is also highly specific for the disease.11 Potential neurologic deficits in patients with aortic dissection include stroke secondary to carotid occlusion, spinal cord syndromes as a result of spinal or intercostal arterial occlusion, and peripheral neuropathy caused by neuronal ischemia or compression of a peripheral nerve by the false lumen.

Alternative Presentations

Abdominal Pain

Abdominal pain is one of the complaints in about 25% of patients with aortic dissection and is the primary complaint in 5% of patients13; such patients invariably have dissection of the descending aorta. The pain is usually midline but can be referred to the flank, frequently on the left. The pain is typically out of proportion to the physical findings.

Painless Dissection

About 6% of patients with aortic dissection do not have pain. Half of these patients have previously undergone cardiovascular surgery, which potentially disrupts the thoracic nerves. One third have syncope, 20% have heart failure, and more than 10% have stroke.14 There are numerous reports of patients with painless spinal cord syndromes as well.1 In these difficult cases, picking up clues such as a diastolic murmur, pulse deficit, and an abnormal mediastinum on chest radiography is critical to making the correct diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

In one prospective study, the absence of aortic pain (sudden and severe), a pulse or blood pressure differential, and mediastinal or aortic widening on chest radiography had a sensitivity of 96% for ruling out the diagnosis of aortic dissection. Conversely, the presence of a pulse deficit or a focal neurologic deficit, with positive likelihood ratios of 47 and 33, respectively, markedly raised the probability of aortic dissection.11

Chest Radiography

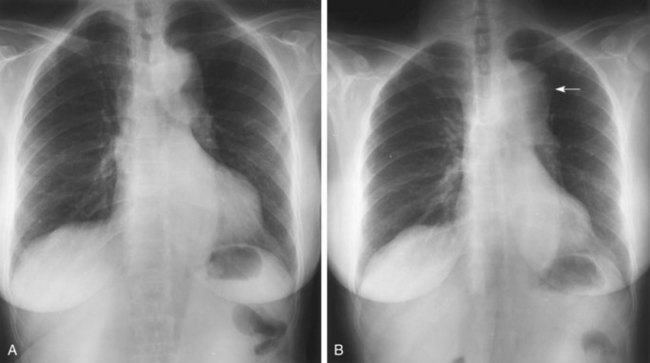

The chest radiograph classically shows a wide mediastinum, predominantly on the right in patients with dissection of the ascending aorta and on the left with dissection of the descending aorta (Fig. 65.4). The physician’s subjective impression, rather than formal measurements, is the best indicator of whether the mediastinum is wide. A widened mediastinum is not a sensitive indicator of aortic dissection. It probably occurs in about 60% of cases, but some reports note a widened mediastinum in less than 20%.3,10 Other abnormalities of the aorta, such as inward displacement of intimal calcification and a double aortic shadow, may be observed. Pleural effusion may also occur, usually on the left.

D-Dimer

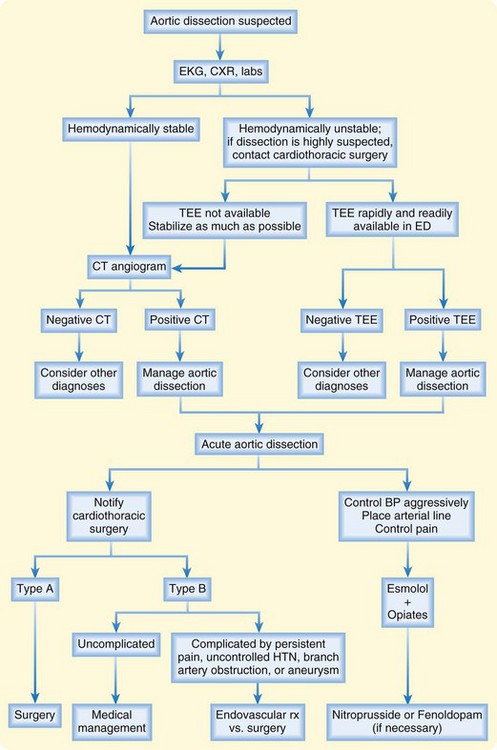

After the history, physical examination, ECG, and chest radiography, the clinician must decide whether aortic dissection is a reasonable possibility (Fig. 65.5). If so, additional testing is required.

Numerous small studies have demonstrated that the serum biomarker D-dimer is useful for excluding the diagnosis. A meta-analysis that included seven studies with a total of 300 patients with dissection found that D-dimer—at the 500-ng/mL cutoff value commonly used for excluding pulmonary embolism—is 97% sensitive for acute aortic dissection.16 D-dimer is probably inadequately sensitive in patients with subacute manifestations and those with pure intramural hematoma. In acute manifestations in which the pretest probability of dissection is low, it is reasonable to use D-dimer to exclude the diagnosis and forego further testing.

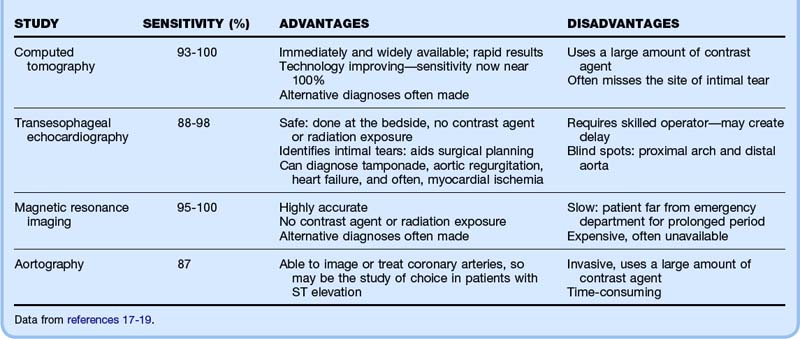

If the pretest probability is not low, the manifestation is subacute, or D-dimer levels are elevated, an advanced imaging study is required (Table 65.3). All of the modalities described are highly sensitive (98% to 100%) and specific (95% to 98%) and thus in most cases will definitively rule in or rule out dissection.17

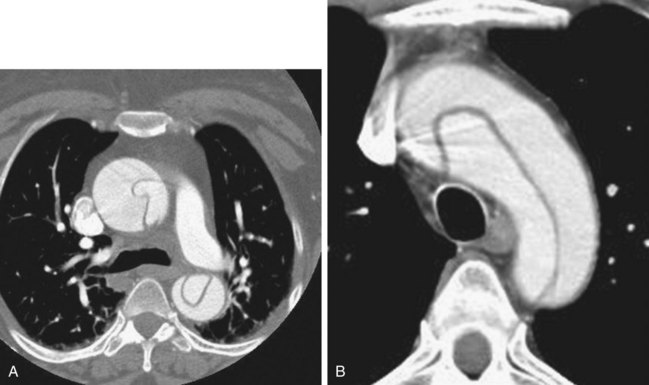

Computed Tomography

The diagnostic study of choice is computed tomographic (CT) angiography of the aorta (Fig. 65.6). It is immediately available in most EDs and can be interpreted quickly by a radiologist. It is highly sensitive for dissection, especially as CT technology advances—in fact, a 2005 study reported that multidetector CT scanning was 100% accurate in patients with suspected acute aortic disease.18 Moreover, when its results are negative for dissection, CT scanning frequently shows alternative serious disease to explain the patient’s symptoms. In the ED, CT scanning is more readily available than transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and most patients (even if somewhat clinically unstable) are able to undergo CT scanning to enable the diagnosis to be made.

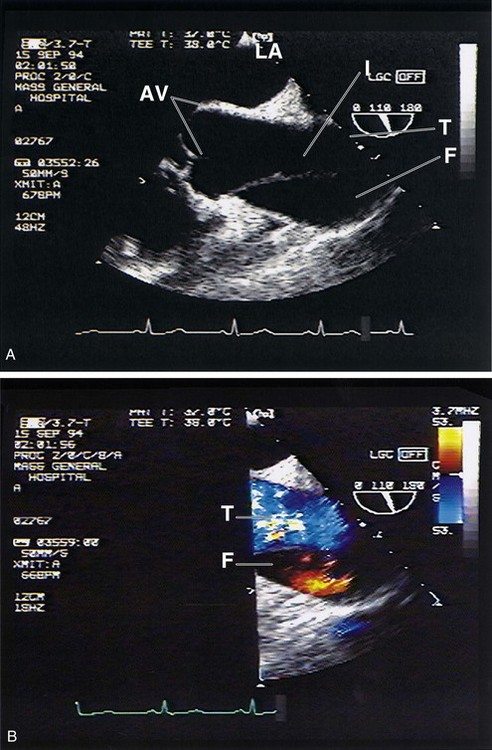

Transesophageal Echocardiography

Generally performed by a cardiologist, TEE is an alternative technique in patients with renal failure, which is a relative contraindication to CT scanning (Fig. 65.7). TEE is as sensitive as CT scanning for type A aortic dissection but may be slightly less sensitive for type B lesions19; TEE has the advantage of assessing the aortic valve and pericardial space for complications of type A dissection. It may also detect focal ventricular wall motion abnormalities suggesting myocardial ischemia as the cause of the patient’s symptoms. Finally, unlike CT scanning, TEE usually identifies the exact location of the intimal tear and assesses overall cardiac function, which aids in operative planning and risk assessment. The downside of TEE, especially during off hours, is the difficulty performing TEE on an emergency basis. Nonetheless, cardiothoracic surgeons may request the study even when dissection has already been diagnosed.

Treatment

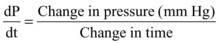

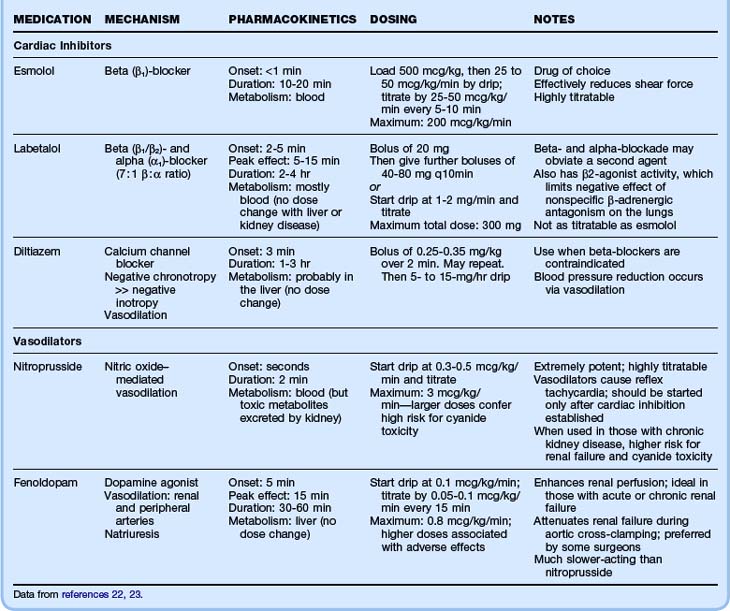

The main goal of ED care is to identify the disease and then manage the patient’s blood pressure and heart rate to minimize aortic shear force. The goal for systolic blood pressure is 100 to 120 mm Hg,20 and the goal for the heart rate is a rate lower than 60 beats/min.21 Note that the blood pressure goal is independent of the patient’s baseline blood pressure, unlike the approach to most hypertensive emergencies. Therefore, the clinician must watch for signs of iatrogenic end-organ malperfusion. Very short-acting antihypertensives should be used and administered as drips to precisely titrate the dose to effect.

Table 65.4 summarizes the intravenous hypertensive agents used for treatment of aortic dissection.20,22,23 Beta-blockers are the first-line antihypertensive agents in patients with aortic dissection because they most effectively reduce both blood pressure and shear force (in patients with significant asthma, diltiazem can be used instead). The ideal beta-blocker is esmolol because of its short half-life and thus its titratability. If blood pressure control with beta-blockers is limited by bradycardia or a plateau effect, a second antihypertensive agent may be needed, invariably a vasodilator.

Type A aortic dissection generally requires emergency thoracic surgery because the mortality rate in patients who do not undergo surgery increases hourly and is 50% to 80% at 1 month. Typically, the surgeon excises the segment of aorta containing the intimal tears and replaces it with a graft, often with some dissected aorta left in place. The aortic valve frequently needs to be replaced as well. With surgery, survival of patients with type A dissection is improved remarkably, to greater than 95% at 1 year.24 Recently, some experts have advocated nonsurgical management for patients with subacute manifestations or a history of aortic valve replacement (both confer a better prognosis) and for patients with acute stroke or severe comorbid conditions (both confer a worse surgical prognosis).20

Type B dissection is usually treated medically, with a 90% survival rate at 1 month. Type B dissection that is complicated by persistent pain, uncontrolled hypertension, branch artery obstruction, or aneurysm has traditionally required surgery. However, endovascular stent placement and balloon fenestration have become therapeutic options; malperfusion syndromes can be reversed in the vast majority of cases, and the false lumen can often be obliterated, thus reducing the chance of aneurysm development and other future complications.25 Mortality appears to be substantially lower (10% to 15%) with stenting than with surgery (25% to 35%) for complicated type B dissection.26

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

All patients with newly diagnosed aortic dissection should be admitted to the intensive care unit. Patients with type A dissection may go to the operating room first. In the ED, these patients need intensive care unit–level management and should be in a resuscitation bay with a 1 : 1 nurse-to-patient ratio to ensure adequate monitoring of blood pressure and response to therapy (see the Red Flags box).

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

One third of patients seen in the emergency department with aortic dissection do not have chest pain.

Aortic dissection occurs more commonly in winter, even in temperate climates.

Forty percent of patients with dissection have a normal mediastinal width on chest radiographs.

Beware of pseudohypotension, which is a low blood pressure reading caused by occlusion of an extremity by a dissected vessel wall.

Detection of ischemia on an electrocardiogram does not rule out aortic dissection. Always consider dissection in a patient with inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; most ascending aortic dissections involve the right aortic wall, and occasionally the right coronary artery will be occluded.

Appropriate medical management of confirmed dissection involves dropping systolic blood pressure to 100 to 120 mm Hg regardless of the starting blood pressure.

1 Khan IA, Nair CK. Clinical, diagnostic, and management perspectives of aortic dissection. Chest. 2002;122:311–328.

2 Hirst AE, Jr., Johns VJ, Jr., Kime SW, Jr. Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta: a review of 505 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1958;37:217–279.

3 Sullivan PR, Wolfson AB, Leckey RD, et al. Diagnosis of acute thoracic aortic dissection in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:46–50.

4 Meszaros I, Morocz J, Szlavi J, et al. Epidemiology and clinicopathology of aortic dissection. Chest. 2000;117:1271–1278.

5 Clouse WD, Hallett JW, Schaff HV, et al. Acute aortic dissection: population-based incidence compared with degenerative aortic aneurysm rupture. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:176–180.

6 Burt CW. Summary statistics for acute cardiac ischemia and chest pain visits to United States EDs, 1995-1996. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:552–559.

7 Januzzi JL, Isselbacher EM, Fattori R, et al. Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:665–669.

8 Hasham SN, Lewin MR, Tran VT, et al. Nonsyndromic genetic predisposition to aortic dissection: a newly recognized, diagnosable, and preventable occurrence in families. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:79–82.

9 Neinaber CA, Eagle KA. Aortic dissection: new frontiers in diagnosis and management. Part I: from etiology to diagnostic strategies. Circulation. 2003;108:628–635.

10 Klompas M. Does this patient have an acute thoracic aortic dissection? JAMA. 2002;287:2262–2272.

11 Von Kodolitsch Y, Schwartz AG, Nienaber CA. Clinical prediction of acute aortic dissection. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2977–2982.

12 Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283:897–903.

13 Upchurch GR, Nienaber C, Fattori R, et al. Acute aortic dissection presenting with primarily abdominal pain: a rare manifestation of a deadly disease. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:367–373.

14 Park SW, Hutchison S, Mehta RH, et al. Association of painless acute aortic dissection with increased mortality. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1252–1257.

15 Pesola GR, Pesola HR, Lin M, et al. The normal difference in bilateral indirect blood pressure recordings in hypertensive individuals. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:342–345.

16 Shimony A, Filion KB, Motillo S, et al. Meta-analysis of the usefulness of D-dimer to diagnose acute aortic dissection. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1227–1234.

17 Shiga T, Wajima Z, Apfel CC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transesophageal echocardiography, helical computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging for suspected thoracic aortic dissection. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1350–1356.

18 Hayter R, Rhea JT, Small A, et al. Suspected aortic dissection and other aortic disorders: multi-detector row CT in 373 cases in the emergency setting. Radiology. 2005;238:841–852.

19 Moore AG, Eagle KA, Bruckman D, et al. Choice of computed tomography, transesophageal echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and aortography in acute aortic dissection: International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1235–1238.

20 Feldman M, Shah M, Elefteriades JA. Medical management of acute type A aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;15:286–293.

21 Kodama K, Nishigami K, Sakamoto T. Tight heart rate control reduces secondary adverse events in patients with type B acute aortic dissection. Circulation. 2008;118:S167–S170.

22 Veron J, Marik PE. The diagnosis and management of hypertensive crises. Chest. 2000;118:214–227.

23 Mosby’s Drug Consult 2005. Handheld software on CD-ROM. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2005.

24 Tsai T, Fattori R, Trimarchi S, et al. International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection: long-term survival in patients presenting with type A acute aortic dissection: insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Circulation. 2006;114:350–356.

25 Moon MC, Pablo Morales J, Greenberg RK. Complicated acute type B dissection and endovascular repair: indications and pitfall. Perspect Vase Surg Endovasc Ther. 2007;19:146–159.

26 White RA, Miller DC, Criado FJ. Report of the results of thoracic endovascular aortic repair for acute, complicated, type B aortic dissection at 30 days and 1 year from a multidisciplinary subcommittee of the Society for Vacular Surgery Outcomes Committee. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:1082–1090.