Chapter 33 Anticonvulsants in the Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome

Anticonvulsants were first used (carbamazepine) in the 1980s, and this use was recognized by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine standards of practice on the management of restless legs syndrome (RLS).1 In subsequent decades, the uses of anticonvulsants have expanded, particularly in cases of pain such as neuropathic pain. It was this use that first alerted the medical community to the possibility that gabapentin might be effective in RLS,2 when it was used by a pain specialist who serendipitously observed that it also benefited his patients’ RLS. There has been a subsequent tendency to suggest that anticonvulsants may be most beneficial to RLS patients who describe pain as a component of their sensory symptoms, but there is also evidence that anticonvulsants can help RLS in general, including periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) and sleep disruption.

Carbamazepine

Two studies from 1983 and 1984 established carbazepine as useful for RLS. One study3 was a pilot study, but the second4 had the largest sample size of any published RLS study until the 21st century. Telstad and colleagues4 performed a 5-week double-blind study of 170 patients using carbamazepine and placebo. Both arms had significant benefit, but the carbamazepine arm showed significantly greater clinical benefit than the placebo arm. Although carbamazepine was recognized as a guideline in 19991 and endorsed by the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) as probably effective in 2006,5 it has not been widely used by RLS experts in the last decade.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant that has shown therapeutic activity for essential tremor, as well as for several pain-related syndromes such as trigeminal neuralgia, post-herpetic pain, and diabetic neuropathy.2,6,7 Due to its effects on pain and other sensorial symptoms, in addition to the observation of an improvement of sleep in neuropathic pain, it has been suggested that gabapentin might be useful for the treatment of RLS. So far, two short to mid-term double-blind studies and several long-term open studies have shown therapeutic effects in RLS.2,8–11

In one of the earlier studies, Adler and colleagues10 performed an open-label study for up to 6 months on eight patients with RLS. The dosage ranged from 300 to 2400 mg/day, with a mean of 1163 mg/day. The minimum period of treatment was 1 week, and four patients remained on medication for up to 6 months. Four of the eight patients had a beneficial response, and three of them had complete resolution of symptoms. Two patients discontinued the study due to side effects, which included dizziness, nausea, and drowsiness.

In another open-label case series,2 16 RLS patients were treated for a mean of 8 months with a mean dosage of 487 mg/day (SD, 199.6 mg). Based on the patient´s subjective estimation, RLS was relieved in 75% to 100% of the cases, with a mean improvement of 85% (SD, 16%). The drug was well tolerated with just dizziness being reported for two patients, as well as drowsiness and alcohol enhancement each for one patient.

Happe and colleagues8 performed an open study on nine patients diagnosed with idiopathic RLS and included polysomnography among the efficacy measurement. All patients were treated for 6 to 10 months with gabapentin at doses of 300 to 1200 mg, administered 2 hours before bedtime. Sleep studies were performed at baseline as well as 4 weeks after. After the first 4 weeks, all nine patients were still on gabapentin with a mean dose of 733 +/− 400 mg. Moreover, 6 to 10 months later, eight patients were still on gabapentin with a mean dose of 533 +/− 328 mg. There was a significant reduction of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) Rating Scale (IRLS) score, both on short-term and on long-term treatment. Furthermore, indices of motor disturbance and sleep fragmentation, such as the PLM-index, the PLM-arousal index, and the arousal index, were reduced after 4 weeks of treatment. However, no similar improvement was seen on the other sleep parameters. There were only mild and mostly transitory side effects such as numbness, dizziness, sleepiness, and headache. Two patients reported persistent side effects, one with headache and one with sleepiness, but these side effects were only mild and did not lead to discontinuation of treatment with gabapentin. This study was the first to show an improvement in periodic leg movements during sleep (PLMS) during gabapentin treatment.

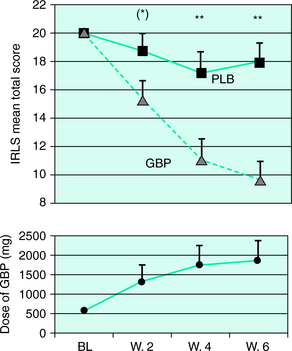

Furthermore, in the only controlled study11 performed on idiopathic RLS patients, 22 of the patients were treated for 6 weeks using a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover (gabapentin versus placebo) design. Patients were rated at scheduled intervals by the IRLS, and a sleep study was performed at the end of each treatment period. Compared with placebo, gabapentin was associated with a reduction of sensory and motor symptoms (Fig. 33-1). In addition, sleep studies showed a significant reduction in PLMS index and an improvement in sleep architecture (increased total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and slow wave sleep, and a decrease in stage 1 sleep). Patients whose symptoms included pain benefited most from gabapentin. The mean effective dosage at the end of the 6-week treatment period was 1855 mg, although therapeutic effects were already observed at the end of week 4 (at a mean of 1391 mg).

Gabapentin has been used in rare comparative trials of RLS treatments. One study has compared the therapeutic effects of gabapentin with a dopaminergic agonist: In a 4-week open clinical trial, eight patients with idiopathic RLS were treated with either 300 mg of gabapentin or 0.5 mg of ropinirole as the initial dose, with a subsequent uptitration until symptoms were relieved. The mean effective dosage of gabapentin was 800 (±397) mg versus 0.78 (±0.47) mg for ropinirole. In both groups, the IRLS scores improved significantly. Polysomnographic data showed a reduction of both periodic leg movements during sleep and the PLMS index in both groups. Side effects were only mild and mostly transient. After 6 to 10 months of follow-up, in most patients, RLS symptoms were still improved. The authors concluded that gabapentin and ropinirole provided a similarly well-tolerated and effective treatment of PLMS and sensorimotor symptoms in patients with idiopathic RLS.12 Taken together with the previous studies suggest that gabapentin is a valid treatment for idiopathic RLS, although further systematized assessment of the long-term effects is necessary.

Two studies have investigated the therapeutic effects of gabapentin in uremic RLS. The first used a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design on 16 patients with uremic RLS who were on hemodialysis.13 Following randomization, patients were treated with either gabapentin (300 mg) or placebo 3 times a week at the end of each haemodialysis session. Using a self-made rating scale based on each of the four RLS diagnostic criteria,14 11 patients responded to gabapentin but not to placebo, 1 patient responded to placebo but not to gabapentin, and 1 patient did not respond to either one. The drug was in general well tolerated, but two patients dropped out during the gabapentin period study due to somnolence and lethargy, and a third patient died of myocardial infarction during treatment with placebo during the first treatment condition. No polysomnographic studies were performed.

Another study compared the therapeutic effects of gabapentin and L-DOPA in uremic RLS.15 Fifteen patients were treated for several weeks with gabapentin or L -DOPA. When both drugs were compared, the effect of gabapentin was superior to L -DOPA for the improvement of general health, body pain, and social functions. Moreover, gabapentin was also superior to levodopa for sleep quality, sleep latency, and sleep disturbance. Of these studies, it can be concluded that gabapentin is a useful treatment for the short-term management of uremic RLS. However, due to its significant renal excretion, caution is required in this type of population on hemodyalisis.

Two additional studies have investigated the effects of gabapentin on periodic leg movement disorder (PLMD). In an open study that was published as an abstract, seven patients who were diagnosed clinically with PLMD underwent sleep studies at baseline and were required to have a PLM index greater than 5 per hour.16 Studies were performed before and 1 month after initiation of treatment with 300 mg of gabapentin. One patient had subjective worsening of the PLM index, and six patients reported subjective improvement, and their mean PLM index decreased from 84 to 54 movements per hour. There was mild to moderate improvement in sleep architecture and sleep continuity. A minor improvement of daytime sleepiness was noted. However, the abstract did not provide any information on whether nighttime sleep parameters improved, nor did it contain any long-term data. However, it represented the first report in the literature suggesting that gabapentin might exert effects on PLMs.

In the second study, Ehrenberg and colleagues7 performed a double-blind crossover study on 13 patients diagnosed with PLMS by polysomnography. Patients were then randomized to receive 4 weeks of gabapentin or placebo following a crossover design. At the end of each treatment condition, a sleep study was performed. No significant differences were seen between gabapentin and placebo regarding the PLM index. However, a significant increase in total sleep time (5.8 hours versus 6.8 hours) and in sleep efficiency (78% versus 91%) was observed under gabapentin. Furthermore, a reduction in the percentage of stage 1 sleep and in the number of full awakenings was observed. Both rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and slow wave sleep showed a nonsignificant trend toward an increase. A subjective benefit was reported by 8 of 13 patients. In summary, these results show the sleep-inducing and sleep-consolidating effects in PLMD in gabapentin and support the therapeutic efficacy of gabapentin in improving abnormal motor function in RLS. Taken together, these studies provide increasing evidence that gabapentin might be an effective agent for the treatment of idiopathic and uremic RLS, as noted by the EFNS evidence-based review.5 Nevertheless, further long-term studies are needed to assess tolerance, absence of RLS augmentation, and maintenance of efficacy. In addition, further investigation is needed to define the optimal dosage and timing so as to avoid unwanted daytime sedation.

Compounds Related to Gabapentin

Two drugs related to gabapentin are pregabalin and a new drug currently known as XP13512. There is one study published regarding pregabalin and abstract information provided about XP13512. Pregabalin is another ligand of the α2δ calcium channel protein that resembles gabapentin in its therapeutic profile. It is approved in the United States for treatment of epilepsy, post-herpetic neuralgia, and neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. After oral intake, the drug reaches peak blood levels in 1.5 hours, has a half-life of about 6 hours, and is excreted by the kidneys mostly unaltered. Side effects include dizziness, somnolence, dry mouth, edema, blurred vision, weight gain, and difficulties with concentration or attention. Only one open-label study has been published on pregabalin, which found it was effective for 16 of 19 patients with RLS (16 of whom also had a painful neuropathy).17 The average dose was 305 mg with the average duration of therapy of 217 days. Due to this paucity of published studies, we do not know the correct dose ranges for treatment of RLS patients. Typically, pregabalin can be prescribed similar to its use for its other approved indications. It should be started at 50 to 75 mg (1 to 2 hours before the onset of symptoms) and can be increased by 50 to 75 mg on a weekly basis to a maximum of 450 mg/day (in two or three divided doses).

The new gabapentin prodrug, XP13512, is designed to rapidly convert to gabapentin once absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in limited systemic exposure to the intact prodrug.18,19

Other Anticonvulsants With Possible Use in Restless Legs Syndrome

Lamotrigine

This drug, approved in the United States for epilepsy and bipolar disorder is an antiepileptic drug of the phenyltriazine class, chemically unrelated to existing antiepileptic drugs. There is currently only one article, a pilot study of four refractory RLS patients demonstrating some benefit of lamotrigine in three of four subjects.20 The study included three phases: a 3-day drug-free baseline phase, a 3-month phase to titrate lamotrigine, and a 1-month phase at a stable dose. Patients recorded assessments of RLS symptoms and sleep parameters daily. Furthermore, three-day objective assessments at the end of each phase included continuous monitoring with activity meters and a suggested immobilization test. Three patients completed the study and one withdrew due to dizziness. Other side effects (pruritus, dizziness, and chest pain) were mild and resolved without discontinuing medications. Final doses averaged 360 mg/day (250 to 500 mg). There was a trend, although inconsistent, toward improvement on objective measures of activity or PLMS that deserves further investigation. Additional anecdotal reports have found benefits for RLS using this drug. Clearly, more experience and studies are necessary to ascertain the efficacy and safety of lamotrigine for RLS.

Lamotrigine is metabolized in the liver and excreted through the kidneys. It reaches peak concentration in about 2 hours and has a half-life of 25 to 32 hours. Common side effects include dizziness, ataxia, somnolence, headache, diplopia, blurred vision, nausea, vomiting, and rash. Rarely, serious skin conditions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, may occur. There are no real dosing guidelines for lamotrigine in RLS. However, the one pilot study found that dosing similar to its use in epilepsy was reasonable (Table 33-1). This medication is generally well tolerated; however, the long titration schedule that is necessary to avoid the dermatologic concerns makes this a difficult medication to institute and it is probably more useful as an add-on treatment.

| Week | Dose of Lamotrigine |

|---|---|

| 1 and 2 | 25 mg/day |

| 3 and 4 | 50 mg/day |

| 5 | 100 mg/day |

| 6 to 9 | Increase by 100 mg/day each week to a maximum of 500 mg/day (in two divided doses) |

Levetiracetam

Levetiracetam is approved in the United States for epilepsy. After oral intake, it reaches peak concentration in about 1 hour and has a half-life of about 6 to 8 hours and is not metabolized but is excreted by the kidneys. Side effects include somnolence, asthenia, infection, dizziness, ataxia, and paresthesia. There is only one article examining this drug in two patients with RLS.21 Both these patients had RLS symptoms refractory to dopamine agonists and the more commonly used anticonvulsant drugs (gabapentin and carbamazepine) but responded to 500 to 1000 mg of levetiracetam at bedtime and sustained this benefit for over 21 months.

Oxcarbazepine

There is only one article discussing the dosing of oxcarbazepine for RLS that used 150 mg twice daily to successfully treat a case of paroxetine-induced RLS.22 The dosing for epilepsy in adults is considerably higher, starting with 300 mg twice daily and is increased by 300 mg/day to a total of 1200 mg/day. Further study is necessary to determine the efficacy, safety, and dosing of this drug for treating RLS.

Tiagabine

There are no published studies on tiagabine and RLS. However, there is some clinical experience providing anecdotal reports of benefit. When used for RLS, doses similar to those used for epilepsy have been employed (Table 33-2). In general, tiagabine has been demonstrated to improve sleep quality (increased slow wave sleep) and sleep maintenance,23 which may be helpful for some people with RLS. However, it does not decrease the latency to sleep.

| Week | Initiation and Titration Schedule | Total Daily Dose |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initiate at 4 mg once daily | 4 mg/day |

| 2 | Increase total daily dose by 4 mg | 8 mg/day (in two divided doses) |

| 3 | Increase total daily dose by 4 mg | 12 mg/day (in three divided doses) |

| 4 | Increase total daily dose by 4 mg | 16 mg/day (in two to four divided doses) |

| 5 | Increase total daily dose by 4 to 8 mg | 20 to 24 mg/day (in two to four divided doses) |

| 6 | Increase total daily dose by 4 to 8 mg | 24 to 32 mg/day (in two to four divided doses) |

Topiramate

There is a single published study24 using topiramate in RLS that found it to be an effective treatment over a period of 90 days. The mean effective dose was established at 42 mg with a range of 25 to 100 mg. This was an unusual patient population because most symptoms were in the feet; three subjects dropped out, two for sleepiness. A striking weight loss was noted as a possible adverse effect. Topiramate should be started at 25 mg once or twice daily (depending on the time of onset of RLS symptoms), and this dose can be increased by 25 mg on a weekly basis until symptoms are relieved.

Valproic Acid

At present, only one study has examined the use of this drug for RLS.25 This study compared valproic acid (600 mg) and L-DOPA/benserazide (200/50 mg) using a placebo-controlled, crossover, double-blind method and found no major difference between the efficacy of these drugs over a 3-week test period. However, they found that the decrease of intensity and duration of RLS symptoms were more pronounced with valproic acid than with L-DOPA. Until further studies are performed, the only guidelines for dosing come from the one study,25 which used a fixed dose of 600 mg. In general, valproic acid should be started at 250 mg and increased by 250 mg on a weekly basis. It can be taken up to 2 or 3 times daily with a maximum daily dose not to exceed 1250 mg.

Zonisamide

Zonisamide is approved in the United States for the treatment of epilepsy. After oral intake, it reaches peak concentration in about 2 to 6 hours but has a very long half-life of 63 hours, allowing for once-daily use. It is partially metabolized in the liver through the cytochrome P450 system and excreted through the urine. Adverse reactions include somnolence (especially at higher doses), anorexia, dizziness, headache, nausea, and agitation or irritability. There is one case report of a 27-year-old woman with a family history of RLS who, while being treated with zonisamide 200 to 400 mg for epilepsy, developed new-onset RLS.26 It is not clear whether this is an erratic case or represents a problem in treating RLS with this drug.

1. Chesson ALJr, Wise M, Davila D, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Report. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep. 1999;22:961-968.

2. Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Management of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin (Neurontin) [letter]. Sleep. 1996;19:224-226.

3. Lundvall O, Abom PE, Holm R. Carbamazepine in restless legs. A controlled pilot study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;25:323-324.

4. Telstad W, Sorensen O, Larsen S, et al. Treatment of the restless legs syndrome with carbamazepine: A double blind study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288:444-446.

5. Vignatelli L, Billiard M, Clarenbach P, et al. EFNS guidelines on management of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in sleep. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:1049-1065.

6. Gorson KC, Schott C, Herman R, et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: A placebo controlled, double blind, crossover trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:251-252.

7. Ehrenberg B, Wagner A, Corbett K, Rogers W. Double-blind trial of gabapentin for periodic limb movements of sleep: Preliminary results [abstract]. Neurology. 1998;50:A276.

8. Happe S, Klosch G, Saletu B, et al. Treatment of idiopathic restless legs syndrome (RLS) with gabapentin. Neurology. 2001;57:1717-1719.

9. Ehrenberg B. Importance of sleep restoration in co-morbid disease: Effect of anticonvulsants. Neurology. 2000;54:S33-S37.

10. Adler CH. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1997;20:148-151.

11. Garcia-Borreguero D, Larrosa O, de la Llave Y, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin: A double-blind, cross-over study. Neurology. 2002;59:1573-1579.

12. Happe S, Sauter C, Klosch G, et al. Gabapentin versus ropinirole in the treatment of idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Neuropsychobiology. 2003;48:82-86.

13. Thorp ML, Morris CD, Bagby SP. A crossover study of gabapentin in treatment of restless legs syndrome among hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:104-108.

14. Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

15. Micozkadioglu H, Ozdemir FN, Kut A, et al. Gabapentin versus levodopa for the treatment of restless legs syndrome in hemodialysis patients: An open-label study. Ren Fail. 2004;26:393-397.

16. Freij WW, Yacoub G, Nagaria M, et al. Effects of gabapentin on periodic limb movements of sleep [abstract]. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:506.

17. Sommer M, Bachmann CG, Liebetanz KM, et al. Pregabalin in restless legs syndrome with and without neuropathic pain. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;115:347-350.

18. Cundy KC, Branch R, Chernov-Rogan T, et al. XP13512 [(±)-1-([(alpha-isobutanoyloxyethoxy)carbonyl]aminomethyl)-1-cyclohexane acetic acid], a novel gabapentin prodrug: I. Design, synthesis, enzymatic conversion to gabapentin, and transport by intestinal solute transporters. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:315-323.

19. Cundy KC, Annamalai T, Bu L, et al. XP13512 [(±)-1-([(alpha-isobutanoyloxyethoxy)carbonyl]aminomethyl)-1-cyclohexane acetic acid], a novel gabapentin prodrug: II. Improved oral bioavailability, dose proportionality, and colonic absorption compared with gabapentin in rats and monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:324-333.

20. Youssef EA, Wagner ML, Martinez JO, et al. Pilot trial of lamotrigine in the restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2005;6:89.

21. Della Marca G, Vollono C, Mariotti P, et al. Levetiracetam can be effective in the treatment of restless legs syndrome with periodic limb movements in sleep: Report of two cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:566-567.

22. Ozturk O, Eraslan D, Kumral E. Oxcarbazepine treatment for paroxetine-induced restless leg syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:264-265.

23. Walsh JK, Zammit G, Schweitzer PK, et al. Tiagabine enhances slow wave sleep and sleep maintenance in primary insomnia. Sleep Med. 2006;7:155-161.

24. Perez A. Topiramate use as treatment in restless legs syndrome. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2004;32:132-137.

25. Eisensehr I, Ehrenberg BL, Rogge Solti S, et al. Treatment of idiopathic restless legs syndrome (RLS) with slow-release valproic acid compared with slow-release levodopa/benserazid. J Neurol. 2004;251:579-583.

26. Chen JT, Garcia PA, Alldredge BK. Zonisamide-induced restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2003;60:147.