Chapter 83 Anticoagulation in Atrial Arrhythmias

Current Therapy and New Therapeutic Options

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an independent risk factor for stroke and the direct cause of 15% to 20% of all strokes.1 Anticoagulation reduces the relative risk by 68% and all-cause mortality by 33%.2 In the United States, approximately 500,000 people have strokes each year.3

Economics of Stroke

The economic costs of stroke are from direct costs for stroke-related morbidity and mortality, estimated at $17 billion per year. Indirect costs from lost income are $13 billion.3 Institutional care is the bulk of post-stroke care cost and varies according to the type of stroke and long-term disability.4 The costs of anticoagulation with warfarin therapy include frequent laboratory monitoring and hospitalization for bleeding complications, including the need for blood transfusions.

Risk Factors for Stroke

Risk markers for a first stroke can be classified according to their potential for modification (nonmodifiable, modifiable, or potentially modifiable) and the strength of evidence (well documented or less well documented) for prevention. Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, gender, low birth weight, race or ethnicity, and genetic factors. Well-documented modifiable risk factors include hypertension, exposure to cigarette smoke, diabetes, AF and certain other cardiac conditions, dyslipidemia, carotid artery stenosis, sickle cell disease, postmenopausal hormone therapy, poor diet, physical inactivity, and obesity and body fat distribution. From the Framingham data, Wang et al found obesity—or, more specifically, body mass index—to be a risk factor for the development of AF.5

Stroke Risk Stratification

CHADS2

The CHADS2 score is the primary risk stratification scheme and was used for the 2006 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology (ACC/AHA/ESC) guidelines for nonvalvular AF.6 The following risk factors are allotted values that guide the administration of anticoagulation: congestive heart failure (CHF), 1; hypertension, 1; age 75 years and older, 1; diabetes mellitus, 1; and stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), 2. For a score of 0 or 1, which indicates low risk or no risk of stroke (lone AF), aspirin therapy (81 or 325 mg) is recommended. For a score of 1 or 2, which indicates intermediate risk, an oral anticoagulant therapy should be recommended if the patient has no contraindications. A score of 3 or greater indicates a high risk for stroke, and oral anticoagulant therapy is recommended (Table 83-1).

Table 83-1 CHADS2 Score Stroke Rates and Recommended Therapy

| CHADS2 SCORE | STROKE RISK % (95% CI) | RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | Aspirin therapy (81 or 325 mg daily) |

| 1 | 2.8 (2.0–3.8) | Oral antithrombotic therapy or aspirin therapy |

| 2 | 4.0 (3.1–5.1) | Oral antithrombotic therapy |

| 3 | 5.9 (4.6–7.3) | Oral antithrombotic therapy |

| 4 | 8.5 (6.3–11.1) | Oral antithrombotic therapy |

| 5 | 12.5 (8.2–17.5) | Oral antithrombotic therapy |

| 6 | 18.2 (10.5–27.4) | Oral antithrombotic therapy |

Data from Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al: Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: Results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation, JAMA 285(22):2864–2870, 2001.

CHA2DS2-VASc

The CHA2DS2-VASc score, recommended by the 2010 ESC guidelines for use by cardiology professionals for the determination of stroke risk, accounts for major and nonmajor stroke risk factors.7 Major risk factors, scored with 2 points, include previous stroke, TIA or systemic embolism, and age 75 years and older. Minor risks, scored with 1 point each, include CHF with impaired left ventricular function (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] <40%), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, female gender, and age 65 to 74 years. A score of 0 indicates very low risk, and either no therapy or aspirin therapy (75 or 325 mg) is recommended. A score of 1 shows a benefit to the use of oral anticoagulant therapy or aspirin therapy. For a score greater than 2, an oral anticoagulant is recommended. Patients with paroxysmal AF should be treated with anticoagulants, as are those with persistent or permanent AF (Table 83-2).

| CHA2DS2-VASC SCORE | ADJUSTED STROKE RATE (% PER YEAR) | RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | No therapy (or aspirin) |

| 1 | 1.3 | Oral anticoagulant (or aspirin) |

| 2 | 2.2 | Oral anticoagulant |

| 3 | 3.2 | Oral anticoagulant |

| 4 | 4.0 | Oral anticoagulant |

| 5 | 6.7 | Oral anticoagulant |

| 6 | 9.8 | Oral anticoagulant |

| 7 | 9.6 | Oral anticoagulant |

| 8 | 6.7 | Oral anticoagulant |

| 9 | 15.2 | Oral anticoagulant |

Data from Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, et al: Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation, Chest 137:263–272, 2010.

Transthoracic Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography is used in risk stratification by evaluating left ventricular function as an indicator of stroke risk. For moderate to severe left ventricular dysfunction, the stroke relative risk is 2.5 times greater than in patients with mild or normal function. By analysis with transthoracic echocardiography, 38% of patients determined to be in a low-risk group were re-categorized to a high-risk group on the basis of findings pertaining to left ventricular function.8 Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is not recommended for risk stratification.

Challenges of Anticoagulation

Anticoagulation therapy confers a reduced stroke rate but it has its challenges, including time in therapeutic range (TTR), frequent monitoring of international normalized ratio (INR), and bleeding risk. Interactions with vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy drug-drug interactions for competing metabolism in the CYP 2C9, drug-food interactions in vitamin K–containing foods, and genetic mutations that make it a challenge to increase TTR, all occur frequently.9

TTR is essential for the prevention of stroke; the ideal frequency of testing of INR values is determined by multiple factors, such as comorbid conditions, diet changes, medication changes, and variable dose response.10 INR values within therapeutic range increased from 48% to 89% when monitoring occurred every 4 days by point-of-care device versus every 28 days in patients with mechanical valves.11 New therapeutic options boast a longer TTR, offering better protection against stroke.12

Current Therapy

Warfarin

Warfarin, a VKA, has been used for the prevention of stroke in the United States since the 1950s. It is an effective anticoagulant that has been proven to reduce the risk of stroke associated with AF. Warfarin reduces stroke relative risk by 62%.12 For primary prevention, the absolute risk reduction with dose-adjusted warfarin was 2.7% per year; for secondary prevention, the absolute risk reduction was 8.4% per year. Aspirin reduced stroke rates by 22%, showing warfarin to be superior to aspirin in the reduction of stroke.13 Warfarin has been standard of care for stroke prevention until an update of the 2006 ACC/AHA recommendations in February 2011, which recommended the use of dabigatran as an acceptable alternative to warfarin therapy in the prevention of stroke in nonvalvular AF.

Aspirin and Clopidogrel

Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel were compared with anticoagulant therapy in the Atrial Fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for Prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W) study to evaluate the efficacy of each therapy for stroke prevention. The study showed oral anticoagulants to be superior to antiplatelet therapy, with a higher annual event rate with aspirin and clopidogrel compared with warfarin (3.93% vs. 5.64%; P < .001). For patients with contraindications for anticoagulant therapy, the ACTIVE A trial showed a reduction in stroke rates with combined aspirin and clopidogrel verses aspirin alone.12

Dabigatran

Dabigatran (Pradaxa) is the first new oral anticoagulant in more than 50 years approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the reduction of stroke risk and systemic thromboembolism in nonvalvular AF. Benefits of dabigatran include prevention of thromboembolism without the need for monitoring. Dabigatran has no food interactions and limited drug interactions. A warning to avoid the use of rifampin, a P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inducer, is included in the FDA label. Interactions with the P-gp inhibitors ketoconazole, amiodarone, verapamil, and quinidine do occur, but no dose adjustments are needed.14

Dabigatran has been evaluated in two major clinical trials, the Prevention of Embolic and Thrombotic Events in Patients with Persistent Atrial Fibrillation (PETRO) study (and the extension study PETRO-EX) and the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) study (and the continuation study RELY-ABLE). In the phase II PETRO study, dabigatran (300 mg, 150 mg, and 50 mg twice daily) was compared with dose-adjusted warfarin or aspirin.15 Major bleeding events occurred most often in the highest dose (300 mg) group of patients who concurrently took aspirin (stopped during the study), and inadequate thromboembolic prevention was seen in the lowest dose (50 mg) group.16 This trial proved pivotal in choosing the correct doses for the evaluation of the drug in the definitive phase III trial.

RE-LY showed the 150 mg twice-daily dose to be superior in the prevention of stroke or systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular AF compared with the warfarin 150 mg twice-daily dose (hazard ratio [HR], 0.65; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52 to 0.81, P = .0001) and 110 mg twice-daily dose (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.58 vs. 0.90; P = .004).14 The 150-mg dose of dabigatran had fewer stroke and systemic thromboembolism rates compared with warfarin and lower rates of hemorrhagic stroke compared with warfarin.14

TEE is not recommended for risk stratification purposes. However, it is useful before cardioversion to evaluate for clots in the left atrial appendage. Anticoagulation is recommended before cardioversion for the prevention of potential complications by thromboembolism. According to the 2010 ESC guidelines, anticoagulation with warfarin is recommended for at least 3 weeks before cardioversion. If no clots are seen in the left atrial appendage on TEE, the time frame can be shortened. Anticoagulation is recommended for 4 weeks to life after cardioversion, depending on stroke risk factors.17 Eighty percent of thromboembolic events occur within 3 to 10 days after cardioversion. In instable AF, cardioversion should be performed without delay.17 In the case of emergency cardioversion, low-molecular-weight heparin is not recommended. Unfractionated heparin should be used and should be followed by 4 weeks of post-cardioversion warfarin administration.18

Use of dabigatran in cardioversion was analyzed from the RE-LY data. The rates of stroke and systemic embolism at 30 days after cardioversion following the recommended 3 weeks of pre-cardioversion anticoagulation were 0.8% (P = .71 vs. warfarin) for the 110-mg dose, 0.3% (P = .40 vs. warfarin) for the 150-mg dose, and 0.6% for warfarin. Major bleeding event rates were similar in the 150-mg group (1.7%) and warfarin group (0.6%), whereas the 110-mg group had more events (0.6%; P = .06 vs. warfarin). Rates of stroke and systemic embolism were low compared with those of warfarin. As Nagarakanti et al have concluded, dabigatran is an alternative to warfarin for cardioversion anticoagulation.19

RE-LY also evaluated the rates of stroke and systemic embolism in VKA-naïve patients compared with the two dose groups (110 mg twice daily and 150 mg twice daily). Being “VKA naïve” was defined as 62 days or less of lifetime VKA exposure. Stroke and systemic embolism rates per year for the 110-mg, 150-mg, and warfarin groups were 1.57%, 1.07%, and 1.69%, respectively. The 150-mg dose was found to be superior to warfarin (P = .005) and the 110-mg dose similar to warfarin (P = .65). Major bleeding rates in VKA-naïve patients were similar in the dose groups compared with warfarin. Intracranial bleeding rates for the 110-mg, 150-mg, and warfarin groups were 3.11%, 3.34%, and 3.57% per year, respectively, with the 110-mg and 150-mg groups having a lower rate than the warfarin group (P < .001 and P = .005, respectively). In the VKA-experienced 110-mg, 150-mg, and warfarin groups, the stroke and systemic embolism rates were 1.51%, 1.15%, and 1.74% per year, respectively, with 110 mg being similar to warfarin (P = .32) and 150 mg superior (P = .007). Major bleeding rates were lower in the 110-mg group and similar to warfarin in the 150-mg group (P = .003 and P = .41, respectively). Intracranial bleeding rates were lower in both groups of dabigatran compared with the warfarin group (P < .001). RE-LY showed that prior VKA exposure did not alter the benefit of dabigatran.20

Stroke rate, broken down by subtype, either ischemic or hemorrhagic, was evaluated in RE-LY. In the 150-mg twice-daily dose group, the HR, compared with the warfarin group, for all stroke events was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.51 to 0.81), 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58 to 0.97) for ischemic stroke, and 0.26 (95% CI, 0.14 to 0.49) for hemorrhagic stroke. The HR of systemic embolism was 0.61 (95% CI, 0.30 to 1.21) versus warfarin. Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily reduced stroke occurrence compared with warfarin.14

On the basis of the evidence of the RE-LY trial, the ACC/AHA/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) published a focused update on management of patients with nonvalvular AF that recommended the use of dabigatran for the prevention of stroke.21 Dabigatran is dosed at 150 mg twice daily and 75 mg twice daily for creatinine clearance of 15 to 30 mL/min. It is not approved for patients with creatinine clearance less than 15 mL/min.

Anticoagulants

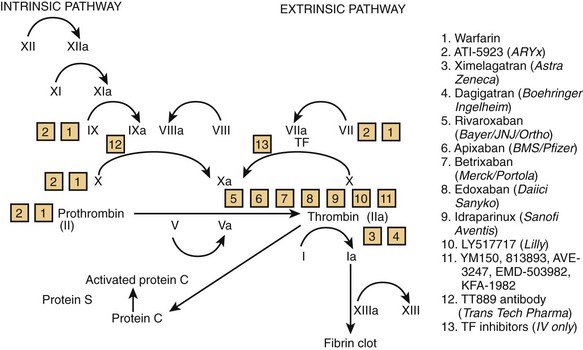

Other anticoagulant medications are in development at various targeted sites of the coagulation cascade (Figure 83-1 and Table 83-3).22

| AGENT | MECHANISM AND SITE OF ACTION | PHASE OF DEVELOPMENT* |

|---|---|---|

| Warfarin (Coumadin) | VKA (Factors II, VII, IX, X) | Established therapy |

| Dabigatran (Pradaxa) | Direct thrombin inhibitor | FDA approval October 2010 |

| ATI-5923 (ARYx) | Novel VKA (Factors II, VII, IX, X) | Phase II complete |

| Ximelagatran | Direct thrombin inhibitor | Phase III complete; suspended by FDA due to liver toxicity |

| Apixaban | Factor Xa inhibitor | Phase III ongoing |

| Betrixaban | Factor Xa inhibitor | Phase II complete |

| Edoxaban | Factor Xa inhibitor | Phase III ongoing |

| Idraparinux | Factor Xa inhibitor | Phase III; terminated |

| LY517717 | Factor Xa inhibitor | Phase II |

| Rivaroxaban | Factor Xa inhibitor | Phase III ongoing |

| GW813893 AVE-3247 EMD-503982 KFA-1982 |

Various | Various stages |

| Tissue factor inhibitors | Tissue factor inhibition at the initiation site | Preclinical models |

VKA, Vitamin K agonist.

* As of publication date of this text.

Data from Goldman PSN, Ezekowitz MD: Principles of anticoagulation and new therapeutic agents in atrial fibrillation, Card Electrophysiol Clin 2(3):479–492, 2010.

Vitamin K Antagonist

VKAs, such as warfarin, work by preventing γ-carboxylation of factors II, VII, IX, and X. Tecarfarin (ATI-5923) is a VKA similar to warfarin but without the CYP-P450 metabolism, which provides a more reliable dose response compared with warfarin. Initial studies with tecarfarin showed a mean of 71.4% of TTR; however, further study is needed.23–25

Factor Xa Inhibitors

Apixaban

Excretion of apixaban is primarily hepatobiliary, and the drug requires twice-daily dosing (half-life of 12 hours). Initial phase II trials evaluated the drug against warfarin in deep venous thrombosis patients for the prevention of thromboembolism. Bleeding events and liver transaminase elevation were similar in both the warfarin and apixaban groups. Phase III trials are ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of apixaban in stroke prevention in nonvalvular AF. Apixaban is being compared with both warfarin therapy (Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation [ARISTOTLE]) and aspirin therapy (Apixaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid to Prevent Strokes [AVERROES]). ARISTOTLE is a phase III trial comparing apixaban with warfarin in more than 18,000 patients; results are expected in late 2011. The recently completed AVERROES study showed apixaban to be superior to aspirin in patients with AF for the reduction of stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic embolism, and vascular death. Additional concurrent studies comparing apixaban with warfarin for deep vein thrombosis, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and advanced metastatic disease are ongoing.26

Betrixaban

Betrixaban is distinct from other factor Xa inhibitors in that it has been developed with an antidote. The phase II study has been completed, and the results presented in March 2010 at the ACC meeting have shown that once-daily betrixaban reduces major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeds in patients with AF and at least one other stroke risk factor compared with dose-adjusted warfarin. The phase III trial is being planned.27

Edoxaban

Edoxaban directly and specifically inhibits factor Xa. It is excreted through the kidneys. The phase III study, Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thromboembolism in Myocardial Infarction 48 (ENGAGE-AF TIMI 48), a double-blind, double-dummy study, is ongoing. It compares prevention of stroke with warfarin and two doses of edoxaban (30 mg and 60 mg daily). The phase II trial findings determined that the rate of bleeding events with the 30-mg and 60-mg daily doses to be comparable with that of warfarin.28

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban, an inhibitor of both free and clot-bound factor Xa in addition to prothrombinase, has shown predictable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in early studies.29,30 Rivaroxaban has renal and hepatobiliary excretion, with increased absorption when taken with food. Rivaroxaban interacts with CYP3A4 inhibitors (macrolide antibiotics, ketoconazole, etc.).31,32 Rivaroxaban is being evaluated in Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET-AF), a phase III double-blind study comparing rivaroxaban with warfarin in patients with nonvalvular AF and one additional stroke risk factor. Results of the ROCKET-AF trial were presented at the AHA 2010 Scientific Session and showed that rivaroxaban was not inferior to warfarin in the prevention of stroke and noncentral nervous system embolism (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66 to 0.96; P < .001). On intention-to-treat analysis, it was not found to be superior to warfarin.33

Other Factor Xa Inhibitors

Other factor Xa inhibitors in clinical development have been studied for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention in both orthopedic surgery and AF. Oral formulations in phase II trials include LY517717 and YM 150. LY517717, evaluated in a phase II trial, showed comparable efficacy and safety at three doses (100, 125, and 150 mg daily) compared with enoxaparin for the prevention of VTE in patients receiving total hip or total knee replacements.34 This compound is metabolized by the liver and safe for patients with renal insufficiency.35 The phase II YM 150 study on patients with hip arthroplasty was completed in 2010. The study found that the tested doses, 30 to 120 mg, were as efficacious and safe as enoxaparin, which is the current recommended therapy.36 Additional compounds being developed include GW813893, AVE-3247, EMD 503982, and KFA-1982.

New Concepts

Factor IX Antibody: TTP889

Factor IX plays a role in clot formation by creating an interaction of activated factor IX and platelets. Factor IX antibodies (IXia) provide selective inhibition between factor IX and platelets by competitively binding to platelet surface membranes.37,38 TTP889 is the only oral agent found to be as effective as heparin without an increased frequency of bleeding events.39 The Factor IX Inhibition in Thrombosis Prevention (FIXIT) trial compared TTP889 with placebo in the prevention of VTE in hip replacement. It has not been evaluated in AF. This trial did not show superiority of TTP889 over placebo (32.1% vs. 28.2%; P > .5).40

Tissue Factor Inhibitors

Tissue factor inhibitors work by inhibiting the initiation of the proteolysis that causes the formation a thrombus and are believed to inhibit neointimal proliferation.41,42 Inhibiting coagulation at the initial step of thrombus formation creates fewer hemorrhagic complications (Table 83-4).43

| AGENT | CLINICAL TRIAL | COMPARISON |

|---|---|---|

| Apixaban | ARISTOTLE | Stroke and VTE prevention vs. warfarin |

| ATI-5923 (ARYx) | Phase II | Time in therapeutic range vs. warfarin |

| Betrixaban | Phase II | Less bleeding vs. warfarin |

| Dabigatran | PETRO | Stroke and VTE prevention vs. warfarin |

| PETRO-Ex | Study drug only | |

| RE-LY | Noninferiority to warfarin | |

| RE-LY-ABLE | Study drug only | |

| Edoxaban | ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 | Stroke and VTE prevention vs. warfarin |

| Idraparinux | AMADEUS BOREALIS-AF |

Stroke and VTE prevention vs. warfarin Noninferiority of biotinylated drug vs. warfarin |

| Rivaroxaban | ROCKET-AF | Stroke and VTE prevention vs. warfarin |

| Tissue factor inhibitors | Preclinical models | Human suitability and bioavailability |

| TTP889 antibody | FIXIT | Proof-of-concept of drug over placebo: failed |

| Ximelagatran | SPORTIFF III SPORTIFF V |

Stroke and VTE prevention vs. warfarin |

VTE, Venous thromboembolism.

Data from Goldman PSN, Ezekowitz MD: Principles of anticoagulation and new therapeutic agents in atrial fibrillation, Card Electrophysiol Clin 2(3):479–492, 2010.

Key References

ACTIVE Writing Group of the ACTIVE Investigators. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9526):1903-1912.

Agnelli G, Haas S, Ginsberg JS, et al. A phase II study of the oral factor Xa inhibitor LY517717 for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after hip or knee replacement. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:746-753.

American Heart Association. ROCKET-AF results. Available at www.theheart.org/article/1148785 Accessed March 20, 2011

Ellis DJ, Usman MH, Milner PG, et al. The first evaluation of a novel vitamin K antagonist, tecarfarin (ATI-5923), in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2009;120(12):1024-1026.

Eriksson BI, Dahl OE, Lassen MR, et al. Partial factor IXa inhibition with TTP889 for prevention of venous thromboembolism: An exploratory study, for the FIXIT Study Group. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:457-463.

Ezekowitz MD, Reilly PA, Nehmiz G, et al. Dabigatran with or without concomitant aspirin compared with warfarin alone in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (PETRO study). Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(9):1419e26.

Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines,. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(4):854e906.

Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263e72.

Nagarakanti R, Eekowitz MD, Oldgren J, et al. Dabigatran verses warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: An analysis of patients undergoing cardioversion. Circulation. 2011;123:131-136.

. New AVERROES data demonstrate investigational apixaban superior to aspirin. Available at www.worldpharmanews.com Accessed March 11, 2011

Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz M, Yousef S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

Singer DE, Albers GW, Dalen JE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: The Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(3 Suppl):429S-456S.

Stellbrink C, Nixdorff U, Hofmann T, et al. Safety and efficacy of enoxaparin compared with unfractionated heparin and oral anticoagulants for prevention of thromboembolic complications in cardioversion of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: The Anticoagulation in Cardioversion using Enoxaparin (ACE) trial. Circulation. 2004;109:997-1003.

The Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369-2429.

Wann LS, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (update on dabigatran): A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123(10):1144-1150.

1 American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update. Available at www.heart.org Accessed November 15, 2010

2 Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: Results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285(22):2864-2870.

3 Taylor TN. The medical economics of stroke. Drugs. 1997;54(Suppl 3):51-57.

4 Tung CY, Granger CB, Sloan MA. Effects of stroke on medical resource use and costs in acute myocardial infarction. GUSTO I Investigators. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries Study. Circulation. 1999;99(3):370-376.

5 Wang TJ, Parise H, Levy D, et al. Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2004;292:2471-2477.

6 Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines,. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(4):854e906.

7 Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263e72.

8 Echocardiographic predictors of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: A prospective study of 1066 patients from 3 clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1316.

9 Singer DE, Albers GW, Dalen JE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: The Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(3 Suppl):429S-456S.

10 Ansell J, Hirsh J, Poller L, et al. The pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: The Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126:204S-233S.

11 Horstkotte D, Piper C, Wiemer M. Optimal frequency of patient monitoring and intensity of oral anticoagulation therapy in valvular heart disease. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1998;5:S19-S24.

12 ACTIVE Writing Group of the ACTIVE Investigators. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9526):1903-1912.

13 Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, Pearce LA. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492-501.

14 Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz M, Yousef S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

15 Wallentin L, Ezekowitz M, Simmers TA, et al. On behalf of PETRO investigators. Safety and efficacy of a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran in atrial fibrillation: A dose finding trial with comparison to warfarin. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(Suppl):482.

16 Ezekowitz MD, Reilly PA, Nehmiz G, et al. Dabigatran with or without concomitant aspirin compared with warfarin alone in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (PETRO study). Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(9):1419e26.

17 The Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369-2429.

18 Stellbrink C, Nixdorff U, Hofmann T, et al. Safety and efficacy of enoxaparin compared with unfractionated heparin and oral anticoagulants for prevention of thromboembolic complications in cardioversion of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: The Anticoagulation in Cardioversion using Enoxaparin (ACE) trial. Circulation. 2004;109:997-1003.

19 Nagarakanti R, Eekowitz MD, Oldgren J, et al. Dabigatran verses warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: An analysis of patients undergoing cardioversion. Circulation. 2011;123:131-136.

20 Ezekowitz MD, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, et al. Dabigatran and warfarin in vitamin K antagonist-naïve and -experienced cohorts with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2010;122:2246-2253.

21 Wann LS, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (update on dabigatran): A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123(10):1144-1150.

22 Goldman PSN, Ezekowitz MD. Principles of anticoagulation and new therapeutic agents in atrial fibrillation. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2010;2(3):479-492.

23 . Tecarfarin (ATI-5923)—Anticoagulation. Available at www.Aryx.com/wt/page/ati5923 Accessed March 10, 2010

24 Carlquist JF, Horne BD, Muhlestein JB, et al. Genotypes of the cytochrome p450 isoform, CYP2C9, and the vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 conjointly determine stable warfarin dose: A prospective study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;22:191-197.

25 Ellis DJ, Usman MH, Milner PG, et al. The first evaluation of a novel vitamin K antagonist, tecarfarin (ATI-5923), in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2009;120(12):1024-1026.

26 . New AVERROES data demonstrate investigational apixaban superior to aspirin. Available at www.worldpharmanews.com Accessed March 11, 2011

27 Ezekowitz M: A randomized clinical trial of three doses of a long-acting oral direct factor Xa inhibitor betrixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. Presented at the ACC 2010 conference. Atlanta, GA, March 15, 2010.

28 Weitz J: Randomized, parallel group, multicenter, multinational study evaluating safety of DU-176b compared with warfarin in subjects with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 7, 2008.

29 Perzborn E, Strassburger J, Wilmen A, et al. In vitro and in vivo studies of the novel antithrombotic agent BAY 59-7939ean oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(3):514-521.

30 Mueck W, Becka M, Kubitza D, et al. Population model of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;45(6):335-344.

31 Kubitza D, Becka M, Zuehlsdorf M, et al. Body weight has limited influence on the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, or pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939) in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47(2):218e26.

32 Kubitza D, Becka M, Zuehlsdorf M, et al. Effect of food, an antacid, and the H2 antagonist ranitidine on the absorption of BAY 59-7939 (rivaroxaban), an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:549e58.

33 American Heart Association. ROCKET-AF results. Available at www.theheart.org/article/1148785 Accessed March 20, 2011

34 Agnelli G, Haas S, Ginsberg JS, et al. A phase II study of the oral factor Xa inhibitor LY517717 for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after hip or knee replacement. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:746-753.

35 Agnelli G, Haas SK, Krueger KA, et al. A phase II study of the safety and efficacy of a novel oral FXa inhibitor (LY-517717) for the prevention of venous thromboembolism following TKR or THR [abstract]. Blood. 2005;106:278.

36 Eriksson BI, Turpie AG, Lassen MR, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism with an oral factor Xa inhibitor, YM150, after total hip arthroplasty. A dose finding study (ONYX-2), for the ONYX-2 Study Group. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(4):714-721.

37 Neels JG, van Den Berg BM, Mertens K, et al. Activation of factor IX zymogen results in exposure of a binding site for low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Blood. 2000;96:3459-3465.

38 Ahmad SS, Rawala-Sheikh R, Walsh PN. Platelet receptor occupancy with factor IXa promotes factor X activation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20012-20016.

39 Rothlein R, Shen JM, Naser N, et al. TTP889, a novel orally active partial inhibitor of FIXa inhibits clotting in two A/V shunt models without prolonging bleeding times [abstract]. Blood. 2005;106:1886.

40 Eriksson BI, Dahl OE, Lassen MR, et al. Partial factor IXa inhibition with TTP889 for prevention of venous thromboembolism: An exploratory study, for the FIXIT Study Group. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:457-463.

41 Ragni M, Cirillo P, Pascucci I, et al. Monoclonal antibody against tissue factor shortens tissue plasminogen activator lysis time and prevents reocclusion in a rabbit model of carotid artery thrombosis. Circulation. 1996;93:1913-1918.

42 Pawashe A, Golino P, Ambrosio G, et al. A monoclonal antibody against rabbit tissue factor inhibits thrombus formation in stenotic injured rabbit carotid arteries. Circ Res. 1994;74:56-63.

43 Himber J, Kirchhofer D, Riederer M, et al. Dissociation of antithrombotic effect and bleeding time prolongation in rabbits by inhibiting tissue factor function. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:1142-1149.