Chapter 22 Antiarrhythmic Drugs

| Abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| AV | Atrioventricular |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| IV | Intravenous |

| NAPA | N-acetylprocainamide |

| NE | Norepinephrine |

| SA | Sinoatrial |

Therapeutic Overview

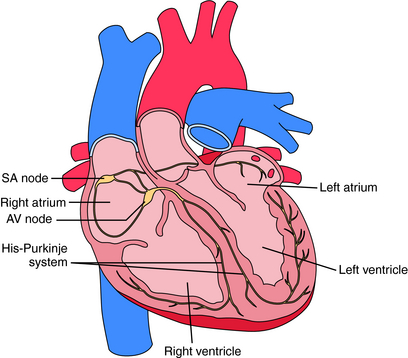

Electrical activation originates in specialized pacemaker cells of the sinoatrial (SA) node, located in the high right atrium near the junction with the superior vena cava (Fig. 22-1). After exiting the SA node, the electrical signal spreads rapidly throughout the atrium, leading to contraction. However, the atria are electrically isolated from the ventricles by the fibrous atrioventricular (AV) ring, with electrical propagation between atrium and ventricles occurring solely through the AV node and His-Purkinje system. The AV node delays the electrical impulse as it passes from atrium to ventricles, providing additional filling time before ejection. The signal then rapidly spreads throughout the ventricles using the Purkinje system, allowing a synchronized contraction.

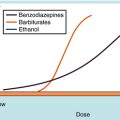

Currently available antiarrhythmic drugs work by one of two mechanisms. They either directly alter

the function of ion channels that participate in a normal heartbeat, or they interfere with neuronal control. Although antiarrhythmic drugs are intended to restore normal sinus rhythm, suppress initiation of abnormal rhythms, or both, their use is hampered by the omnipresent risk of proarrhythmias. In the most famous example, the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial showed that, even though ventricular arrhythmias predictive of sudden death could be suppressed by Na+ channel-blocking

| Therapeutic Overview | |

|---|---|

| Goal: To treat abnormal cardial impulse formation or conduction | |

| Effects: Modify ion fluxes, block Na+, K+, or Ca++ channels modify β adrenergic receptor-activated processes | |

| Drug Action | Uses |

| Na+ channel blockade | Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation or flutter, ventricular tachycardia; digoxin-induced arrhythmias |

| β Adrenergic receptor blockade | Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, atrial or ventricular premature beats, atrial fibrillation or flutter |

| Prolong action potentials and repolarization | Ventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation or flutter* |

| Ca++ channel blockade | Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation or flutter |

| Other | |

| Adenosine | Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia |

| Digitalis glycosides | Atrial fibrillation or flutter with increased ventricular rate |

drugs, their use was associated with an increased incidence of sudden death.

Mechanisms of Action

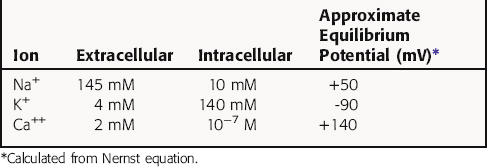

Cardiac myocytes, like other excitable cells, maintain a transmembrane electrical gradient, with the interior of the cell negative with respect to the exterior. This transmembrane potential is generated by an unequal distribution of charged ions between intracellular and extracellular compartments (Table 22-1). Ions can traverse the sarcolemmal membrane only through selective channels or via pumps and exchangers. The resting potential is an active, energy-dependent process, relying on these channels, pumps and exchangers, and large intracellular immobile anionic proteins. Critical components include the Na+/K+-adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) and the inwardly rectifying K+ channel (IK). The Na+/K+-ATPase exchanges 3 Na+ ions from inside of the cell for 2 K+ ions outside, resulting in a net outward flow of positive charge.

where R = the gas constant; T = absolute temperature; F = the Faraday constant; and X is the ion in question. Because the usual intracellular and extracellular concentrations of K+ are 140 and 4 mM, respectively, its equilibrium potential is -94 mV. At rest, the sarcolemmal membrane is nearly impermeable to Na+ and Ca++ but highly permeable to K+. Therefore the resting potential of most cardiac myocytes approaches the equilibrium potential for K+ (-80 to -90 mV). However, the sarcolemmal membrane is dynamic, with a constantly changing permeability to various ions and resultant changes in membrane potential. The membrane potential at any given moment can be calculated based on knowledge of ion concentrations and permeabilities.

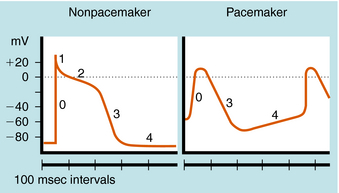

The cardiac action potential is divided into five phases as illustrated in Figure 22-2. The injection of current into a cardiac myocyte, or local current flow from an adjoining cell, can cause the membrane potential to depolarize (become less negative). If the resting potential exceeds a certain threshold, voltage-gated Na+ channels open (Fig. 22-3). Electrical and chemical gradients drive Na+ into the cell, making the membrane potential less negative. During phase 0, there is rapid depolarization of the action potential, Na+ influx is the dominant conductance, and the membrane potential approaches the equilibrium potential for Na+ (+64 mV). However, Na+ channels are open for only a very short time and close quickly. They also cycle through an inactivated state in which they are unable to open and participate in another action potential. Therefore, if a significant percentage of Na+ channels are in the inactivated state, the cell is refractory to further stimulation. The maximal rate of depolarization defines how fast electrical impulses can be passed from cell to cell, determining conduction velocity within a tissue. Slowing of conduction caused by inhibition of Na+ channels is the basis for the actions of Class I antiarrhythmic drugs. Action potentials in nonpacemaker cells are referred to as fast responses because their rate of depolarization is extremely rapid.

The voltage and time dependence of currents through individual ion channels are unique. Na+ channels open at more negative voltages than Ca++ channels, and current kinetics are quite different. Physical structures, known as activation and inactivation gates, help regulate the flow of ions. Because of these gates, Na+ channels are believed to exist in at least three distinct states during the cardiac action potential, as shown in Figure 22-3. At the resting potential, most Na+ channels are in a resting state, available for activation. Upon depolarization, most channels become activated, allowing Na+ to flow into the cell and cause a rapid depolarization. Na+ channels quickly become inactivated, limiting the time for Na+ entry to a few milliseconds or less.

Phase 2, or the plateau phase of the cardiac action potential, is one of its most distinguishing features. In contrast to action potentials in nerves and other cells (see Chapter 13), the cardiac action potential has a relatively long duration of 200 to 500 msec, depending on the cell (see Fig. 22-2). The plateau results from a voltage-dependent decrease in K+ conductance (the inward rectifier) and is maintained by the influx of Ca++ through Ca++ channels that inactivate only slowly at positive membrane potentials. During this phase, another outward K+ current, the delayed rectifier, is slowly activated, which nearly balances the maintained influx of Ca++. As a result, there is only a small change in potential during the plateau, because net current flow is small.

In a nonpacemaker cell, phase 4, or the resting potential, is characterized by a return of the membrane to its resting potential. Atrial and ventricular myocytes maintain a constant resting potential awaiting the next depolarizing stimulus, established by a voltage-activated K+ channel, IK1. The resting potential remains slightly depolarized relative to the equilibrium potential of K+, due to an inward depolarizing leak current likely carried by Na+. During the terminal portions of phase 3, and all of phase 4, voltage-gated Na+ channels are transitioning from the inactivated to the resting state and preparing to participate in another action potential. In a pacemaker cell, however, there is a slow depolarization during diastole. This brings the membrane potential near threshold for activation of a regenerative inward current, which initiates a new action potential (see Fig. 22-2). This is called phase 4 depolarization. In a pacemaker cell in the SA node, phase 4 depolarization brings the membrane potential to a level near the threshold for activation of the inward Ca++ current.

Mechanisms Underlying Cardiac Arrhythmias

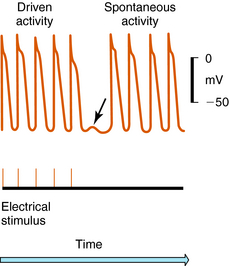

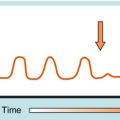

Arrhythmias result from disorders of impulse formation, conduction, or both. Several factors may contribute, such as ischemia with resulting pH and electrolyte abnormalities, excessive myocardial fiber stretch, excessive discharge of or sensitivity to autonomic transmitters, and exposure to chemicals or toxic substances. Disorders of impulse formation can involve either a change in the pacemaker site (e.g., sinus bradycardia or tachycardia) or the development of an ectopic pacemaker. Ectopic activity may arise as a consequence of the emergence of a latent pacemaker, because many cells of the conduction system are capable of rhythmic spontaneous activity. Normally these latent pacemakers are prevented from spontaneously discharging because of the dominance of the rapidly firing SA nodal pacemaker cells. Under some conditions, however, they may become dominant because of abnormal slowing of SA firing rate or abnormal acceleration of latent pacemaker firing rate. Such ectopic activity may result from injury due to ischemia or hypoxia, causing depolarization. Two areas of cells with different membrane potentials may result in current flow between adjacent regions (injury current), which can depolarize normally quiescent tissue to a point where ectopic activity is initiated. Finally, development of oscillatory afterdepolarizations can initiate spontaneous activity in normally quiescent tissue. These afterdepolarizations can occur at the end of phase 3 (Fig. 22-4) and, if large enough in amplitude, reach threshold and initiate a burst of spontaneous activity. Toxic concentrations of digitalis or norepinephrine (NE) can initiate such effects. This mechanism has also been proposed to explain ventricular arrhythmias in patients with the long QT syndrome.

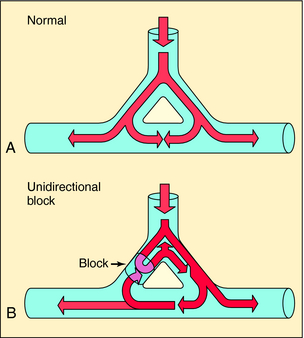

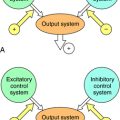

Disorders of impulse conduction can result in either bradycardia, as occurs with AV block, or in tachycardia, as when a reentrant circuit develops. Figure 22-5 shows an example of a hypothetical reentrant circuit. For a reentrant circuit to develop, a region of unidirectional block must exist, and the conduction time around the alternative pathway must exceed the refractory period of the tissue adjacent to the block. Before development of unidirectional block (see Fig. 22-5, A), impulse propagation initially branches as a result of the anatomical properties of the circuit. Some of these impulses collide and extinguish on the other side of the branch point. If an area of unidirectional block develops, impulses around the branch do not collide and become extinguished but may reexcite tissue proximal to the site of block, establishing a circular pathway for continuous reentry (see Fig. 22-5, B). Clinical examples include AV reentrant tachycardia (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome), AV nodal tachycardia, atrial flutter, and incisional/scar (atrial or ventricular) tachycardia. A long reentry pathway, slow conduction, and a short effective refractory period all favor reentrant circuits.

Antiarrhythmic drugs affect normal cardiac function and therefore have the potential for many serious adverse effects. In the most dramatic example, antiarrhythmic drugs have the potential to actually be proarrhythmic. Therefore treatment of a tachycardia, which is a nuisance clinically but not life-threatening, may initiate a life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia—truly a case of the cure being worse than the disease. Such potentially serious side effects require vigilance to ensure proper dosing, proper serum levels, a thorough knowledge of drug-drug interactions, and close follow-up.

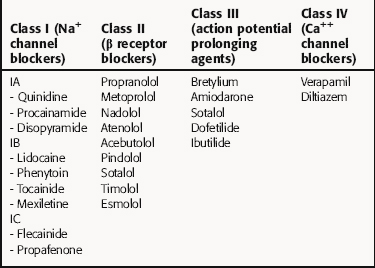

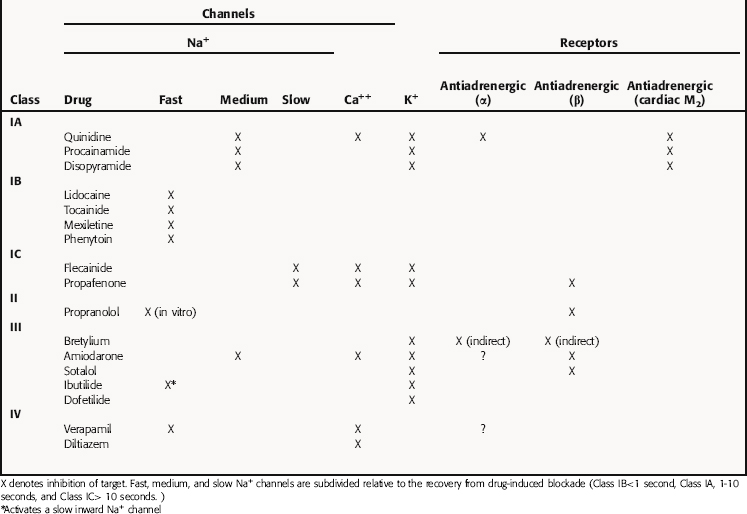

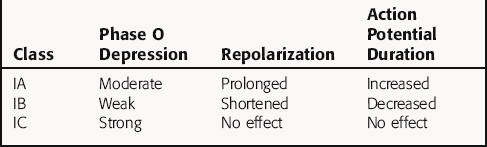

There is no universally accepted classification scheme for antiarrhythmic agents. The most commonly used scheme, the Vaughan-Williams classification, is based on the presumed primary mechanism of action of individual drugs (Table 22-2). This scheme classifies agents that block voltage-gated Na+ channels in class I, those with sympathetic blocking actions in class II, those that prolong action potential duration and refractoriness in class III, and those with Ca++ channel-blocking properties in class IV. However, classification is complicated by the fact that many drugs have multiple actions. As shown in Table 22-3, these drugs often have multiple effects on various targets. Although this scheme is useful in learning the properties of antiarrhythmic agents, all classifications are of limited use for treatment of arrhythmias because of their complex pathophysiology.

Class I agents are subdivided into three groups based on their effects (Table 22-4). Class IA agents slow the rate of rise of phase 0 of the action potential (and slow conduction velocity) and prolong the ventricular refractory period, although they do not alter resting potential. They are also defined on the basis of recovery from drug-induced blockade and directly decrease the slope of phase 4 depolarization in pacemaker cells, especially those arising outside the SA node. Class IB drugs slow conduction and shorten the action potential in nondiseased tissue. The IB agents preferentially act on depolarized myocardium, binding to Na+ channels in the inactivated state. Drugs in class IC markedly depress the rate of rise of phase 0 of the action potential. They shorten the refractory period in Purkinje fibers, although not altering the refractory period in adjacent myocardium.

Quinidine was one of the first antiarrhythmic agents used clinically. It has a wide spectrum of activity and has been used to treat both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. However, its use has significantly diminished because of its high incidence of proarrhythmias and availability of other agents. Quinidine shares most properties with quinine (see Chapter 52). In addition to blocking voltage-gated Na+ channels, quinidine inhibits the delayed rectifier K+ channel. The effect of quinidine on the heart depends on dose and the level of parasympathetic input. A slight increase in heart rate is seen at low doses due to cholinergic blockade, whereas higher concentrations depress spontaneous diastolic depolarization in pacemaker cells, overwhelming its anticholinergic actions and slowing heart rate.

Procainamide, like quinidine, increases the effective refractory period and decreases conduction velocity in the atria, His-Purkinje system, and ventricles. Although having weaker anticholinergic actions than quinidine, it also has variable effects on the AV node. Procainamide increases the threshold for excitation in atrium and ventricle and slows phase 4 depolarization, a combination that decreases abnormal automaticity. Procainamide is used in the treatment of atrial arrhythmias, such as premature atrial contractions, paroxysmal atrial tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation of recent onset, in addition to being effective for most ventricular arrhythmias. Because of proarrhythmia risks, treatment should be limited to hemodynamically significant arrhythmias. Long-term therapy is complicated by the need for frequent dosing and side effects.

Disopyramide suppresses atrial and ventricular arrhythmias and has a longer duration of action than other drugs in its class. Although effective in treating atrial arrhythmias, disopyramide is only approved to treat ventricular arrhythmias in the United States. Despite prominent anticholinergic effects, disopyramide has a pronounced negative inotropic effect, which is so prominent it has been used in therapy of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The electrophysiological effects of disopyramide are nearly identical to those of quinidine and procainamide. However, its anticholinergic effects are far more prominent and limit its utility. Disopyramide blocks voltage-gated Na+ channels, thereby depressing action potentials. Disopyramide also reduces conduction velocity and increases the refractory period in atria. Post-repolarization refractoriness does not occur. Interestingly, abnormal atrial automaticity may be abolished at disopyramide concentrations that fail to alter conduction velocity or refractoriness. Conduction velocity slows and the refractory period increases in the AV node via a direct action, which is offset to a variable degree by its anticholinergic actions. Action potential duration is prolonged, which results in an increase in refractory period of the His-Purkinje and ventricular muscle tissue. Slowed conduction in accessory pathways has been demonstrated. Like quinidine, the effect of disopyramide on conduction velocity depends on extracellular K+ concentrations. Hypokalemic patients may respond poorly to its antiarrhythmic action, whereas hyperkalemia may accentuate its actions.

Lidocaine is a local anesthetic (see Chapter 13) that has long been used to treat arrhythmias. Unlike quinidine, lidocaine rapidly blocks both activated and inactivated Na+ channels. Block of Na+ channels in the inactivated state leads to greater effects on myocytes with long action potentials, such as Purkinje and ventricular cells, compared with atrial cells. The rapid kinetics of lidocaine at normal resting potentials result in recovery from block between action potentials, with no effect on conduction velocity. In partially depolarized cells (such as those injured by ischemia) lidocaine significantly depresses membrane responsiveness, leading to conduction delay and block. Lidocaine also elevates the ventricular fibrillation threshold.

Phenytoin is an anticonvulsant (see Chapter 34) that has been used as an antiarrhythmic agent for decades. Its actions are similar to those of lidocaine. It depresses membrane responsiveness in the ventricular myocardium and His-Purkinje system to a greater extent than in the atrium.

Class II Antiarrhythmics: β Adrenergic Receptor Antagonists

The antiarrhythmic properties of β receptor antagonists result from two major actions: (1) blockade of myocardial β1 receptors, and (2) direct membrane-stabilizing effects at higher concentrations related to blockade of Na+ channels. Propranolol is the prototypical β receptor blocker, and, in addition to blocking β1 receptors in the heart, also has direct membrane-stabilizing effects in atrium, ventricle, and His-Purkinje system. It causes a slowing of SA nodal and ectopic pacemaker automaticity and decreases AV nodal conduction velocity by virtue of its ability to block intrinsic sympathetic activity. There is little change in action potential duration and refractoriness in atrium, ventricle, or AV node. The β receptor antagonists currently used for arrhythmias (see Table 22-2) may be differentiated by their pharmacokinetics, selectivity for β1 receptors, lipophilicity, and intrinsic sympathomimetic effects. A more complete discussion of these drugs is provided in Chapter 11.

Bretylium is a unique class III agent that was first introduced for treatment of essential hypertension but was subsequently shown to suppress ventricular fibrillation associated with acute myocardial infarction. Bretylium selectively accumulates in sympathetic ganglia and postganglionic adrenergic neurons and inhibits NE release. Bretylium has been demonstrated experimentally to increase action potential duration and effective refractory period without changing heart rate.

Calcium channel-blocking drugs are used to slow the rate of AV conduction in patients with atrial fibrillation or to slow ectopic atrial pacemakers. Calcium channel blockers have also been used for treating idiopathic left ventricular tachycardia arising from the posterior fascicle. These agents are discussed extensively in Chapter 20.

Adenosine is an endogenous nucleoside produced from the metabolism of adenosine triphosphate. Adenosine activates the same G-protein coupled outward K+ current as acetylcholine (see Chapter 10). Adenosine receptors are located on atrial myocytes and myocytes in the SA and AV nodes, and stimulation leads to hyperpolarization of the resting potential. Effects include a decrease in slope of phase 4 spontaneous depolarizations and shortening of action potential durations. Effects are most dramatic in the AV node and result in transient conduction block. This effect terminates tachycardias, which use the AV node as a limb of a reentrant circuit. There is no effect on the ventricular myocardium, because this K+ channel is not expressed in the ventricle.

Pharmacokinetics

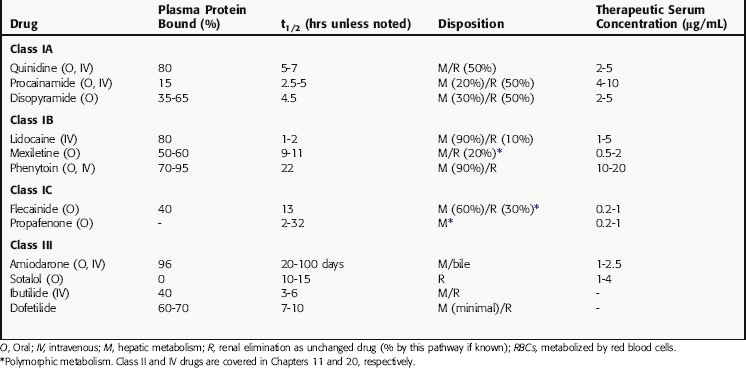

Pharmacokinetic parameters of selected antiarrhythmic drugs are summarized in Table 22-5. The pharmacokinetics of β receptor blockers are discussed in Chapter 11 and Ca++ channel blocking drugs in Chapter 20.

Procainamide is metabolized in the liver by acetylation to N-acetylprocainamide (NAPA), which has class III actions and a longer serum t1/2 than procainamide. In the United States, approximately half of the population (90% of Asians) is homozygous for the N-acetyltransferase gene and are termed rapid acetylators (see Chapter 2). These individuals have a higher concentration of plasma NAPA than procainamide at steady-state. When its concentration exceeds 5 ng/mL, NAPA can contribute to the antiarrhythmic actions of procainamide because of its class III actions that prolong repolarization. Concentrations greater than 20 ng/mL have been associated with adverse effects, including torsades de pointes.

Relationship of Mechanisms of Action to Clinical Response

Quinidine has potent anticholinergic properties that cause effects opposite to those due to its direct effects in parasympathetically innervated regions of the heart. After initial administration, there may be a small SA nodal tachycardia and an increase in AV nodal conduction velocity (decrease in PR interval) as a result of its indirect anticholinergic effects. These are usually followed by direct effects, including a decrease in heart rate and a slowing of AV nodal conduction velocity (increase in PR interval). At therapeutic concentrations the QRS complex often shows slight widening as a result of a decrease in ventricular conduction velocity. The QT interval is lengthened because of the prolonged action potential in the ventricular myocardium.

The β receptor blockers at therapeutic doses prolong the PR interval with occasional shortening of the QT interval. These drugs are reasonably efficacious in suppressing ventricular ectopic pacemakers and are first-line therapy for most supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias. They have been demonstrated to be effective in decreasing overall mortality rate after a myocardial infarction. Agents such as metoprolol and acebutolol (but not propranolol) have a greater selectivity for β1 receptors than for β2 receptors (see Chapter 11). There are also differences between these compounds with regard to their effects on cardiac channels and their intrinsic sympathomimetic activities. Esmolol, a short-acting agent, may be used for acute conversion or ventricular rate control.

Pharmacovigilance: Side Effects, Clinical Problems, and Toxicity

The negative inotropic effects of disopyramide may precipitate heart failure in patients with or without preexisting depression of left ventricular function. Parasympatholytic effects, including urinary retention, dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, and worsening of preexisting glaucoma (see Chapter 10), may require discontinuation of therapy. Disopyramide should not be used in patients with uncompensated congestive heart failure, glaucoma, hypotension, urinary retention, and baseline prolonged QT interval.

Lidocaine does not have negative hemodynamic effects at therapeutic concentrations and is well tolerated, even in significant ventricular dysfunction. However, excessively rapid injection or high doses may cause asystole. Most toxic side effects are caused by its local anesthetic effects on the CNS and include drowsiness, tremor, nausea, hearing disturbances, slurred speech paresthesias, disorientation, and at high doses, psychosis, respiratory depression, and convulsions (see Chapter 13).

Phenytoin at high levels can produce adverse CNS effects, including vertigo, nystagmus, ataxia, tremors, slurring of speech, and sedation. Because of its long t1/2 and the nonlinear relationship between dose and clearance, considerable variations in response to an oral dose are typical. Rapid IV administration may produce transient hypotension from peripheral vasodilation and direct negative inotropic effects (see Chapter 34).

The β receptor antagonists should be used with caution when combined with other drugs that also slow AV nodal conduction velocity, because their effects may be synergistic. These agents are generally contraindicated in patients with existing AV nodal conduction disturbances, congestive heart failure, or bronchial asthma. Their toxicity and side effects are described in Chapter 11.

Adenosine leads to transient AV block, which is generally well tolerated. Prolonged AV block may be observed

| Quinidine | Diarrhea, precipitates arrhythmias; torsades de pointes, elevates digoxin concentrations, vagolytic effects |

| Procainamide | Arrhythmias, granulocytopenia, fever, rash, lupus-like syndrome |

| Disopyramide | Precipitates congestive heart failure, anticholinergic effects |

| Lidocaine | CNS effects (dizziness, seizures), first-pass metabolism |

| Phenytoin | CNS effects, hypotension |

| Mexiletine | CNS effects |

| Flecainide | Negative inotropic effect, proarrhythmogenic, CNS side effects |

| Propafenone | CNS effects, proarrhythmogenic |

| β receptor blockers | Negative inotropic and chronotropic effects; precipitates congestive heart failure, AV conduction block |

| Amiodarone | Hypotension, pneumonitis, bradycardia; precipitates congestive heart failure, photosensitivity, thyroid abnormalities |

| Sotalol | Modest negative inotropic and chronotropic effects, torsades des pointes |

| Dofetilide | Torsades de pointes |

| Ibutilide | Torsades de pointes |

| Bretylium | Hypotension, nausea |

| Verapamil | Hypotension, negative inotropic and chronotropic effects |

| Adenosine | Atrial fibrillation, bronchospasm, prolonged AV block, flushing |

in patients with AV node disease, and profound sinus bradycardia may be observed in patients with sick sinus syndrome. Heart transplantation patients have also been documented to have a prolonged effect from adenosine. Adenosine shortens the refractory period of atrial myocytes, which may lead to initiation of atrial fibrillation. In patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, this may result in rapid conduction across the accessory pathway, which is not blocked by adenosine and ventricular fibrillation. Adenosine may also trigger bronchospasm in patients with asthma. Although the t1/2 of adenosine is less than 10 seconds, bronchospasm may persist for up to 30 minutes by an unknown mechanism.

New Horizons

(In addition to generic and fixed-combination preparations, the following trade-named materials are some of the important compounds available in the United States.*)

pace or defibrillate the heart. Amiodarone, flecainide, lidocaine, propafenone, and mexiletine all lead to increased defibrillation thresholds, whereas sotalol and dofetilide cause them to decrease.

Drugs for cardiac arrhythmias. 2007 Drugs for cardiac arrhythmias. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2007;5:51-58.

Reddy. 2008 Reddy VY. Atrial fibrillation: Unanswered questions and future directions. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:237-258.

Roden. 2004 Roden DM. Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1013-1022.