Chapter 52 Anterior Midline Approaches to the Skull Base

Diagnostic Evaluation

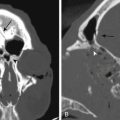

Several essential issues guide our evaluation of cranial base neoplasms: (1) tumor biology and its extent, (2) tumor composition, and (3) relationship of the tumor to the ICA and its importance to cerebral circulation (Fig. 52-1).

Tumor biology is best determined by preoperative histologic evaluation obtained after biopsy. New endoscopic instrumentation permits access to many skull base sites for direct visualization and tissue biopsy, or an open biopsy can be performed. The tumor extent determines the potential for surgical resection of the neoplasm. This is currently best determined by multiplanar CT as well as MRI. Both tests are also very useful in assessing the character of the lesion in terms of its vascular, bony, or soft-tissue content. The location of the ICA, and its contribution to the tumor vascularity as well as the relationship of this vessel to the tumor perimeter, are assessed by MRI, MR angiography, or invasive angiography. The tolerance of the patient to temporary occlusion of the ICA can be evaluated with a series of tests known as temporary balloon occlusion test and xenon blood flow studies.1 These tests permit us to estimate the risk of neurologic deficit with a permanent occlusion in the ICA.

Selected Tumors

Carcinoma

Carcinoma that involves the anterior cranial base originates primarily in the paranasal sinuses, the nose and nasopharynx, or occasionally as a metastatic disease. Carcinoma of the nose and sinuses makes up less than 1% of all malignancies. It carries an overall 30% 5-year survival rate. In general, the prognosis of a patient with a carcinoma is very much related to the histologic type. Anaplastic carcinoma must be differentiated from lymphoma and melanoma with leukocyte common antigen and S-100 protein. Anaplastic carcinoma appears to be a separate entity from poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, which still exhibits some squamous differentiation. It is found more often in women, with occurrence on the left side predominant. Among these patients, 33% develop cervical metastases, but only 70% of these have obvious evidence of bone destruction on radiographs. The survival of patients with anaplastic carcinoma varies with the site of origin. If it occurs in the nose, the 5-year survival rate is 40%. If it originates in the sinuses, the 5-year survival rate decreases to 15% (see Thorup et al.2).

The nasal passages and the sinuses are intimately related, permitting tumor to spread easily from one cavity to the other. Therefore, ethmoid sinuses are often involved secondarily by tumor spread from the nasal cavity or the maxillary sinus. This is reflected in the fact that isolated ethmoid carcinomas compose no more than 5% to 20% of all carcinomas involving the ethmoid sinus. The initial symptoms are usually insidious and trivial, accounting for a significant delay of diagnosis from the onset of symptoms. Sixty to 75% of patients with malignant tumors of the ethmoid sinuses do not survive for 5 years. The ethmoid sinus is closely related to the orbit. Both the orbit and the ethmoid sinus are simultaneously involved in 60% of malignant sinus neoplasms, and 45% of the patients are likely to require orbital exenteration. Most sinus tumors arise from the mucous membrane lining that is in continuity with the mucosa of the remaining sinuses, nasopharynx, and lacrimal draining system. The respiratory mucosa of the ethmoid sinus gives rise to two types of neoplasm. The first is squamous cell carcinoma, arising from the metaplastic epithelium. Of all malignant neoplasms of the sinuses, 75% to 95% will be squamous cell carcinomas, and the ethmoid sinus is the second most common site for this neoplasm. The second is a glandular tumor, arising from mucous glands. The submucosal glands give rise to adenocarcinomas or adenoid cystic carcinomas. Adenocarcinoma occurs most frequently in the ethmoid sinus, and its behavior is similar to that of squamous cell carcinoma. There is some suggestion that this tumor is found more frequently among workers in woodworking industries than in the population in general.3 The lymphatic drainage from the ethmoid sinus is into the superior cervical chain and the retropharyngeal nodes. The incidence of metastases at the time of diagnosis is low, but 25% to 35% of patients will eventually develop metastatic disease. Distant metastases may occur in up to 18% of the cases.4

Esthesioneuroblastoma

This is a rare tumor originating from the olfactory epithelium and represents 3% of all intranasal neoplasms. It was originally described by Berger and Luc.5 This tumor has been identified under different terms, including olfactory neuroblastoma, esthesioneurocytoma, and olfactory esthesioneuroblastoma. It arises from cells of neural crest origin and resembles childhood neuroblastoma. The tumor does contain neurosecretory granules and is linked to other neural crest tumors, such as carcinoid, chemodectoma, and pheochromocytoma. It occurs most frequently in the third decade of life and is more common in males. Unilateral nasal obstruction and epistaxis are the most common symptoms. The tumor may fill the nose and paranasal sinuses and involve the cribriform plate.

A staging system has been proposed by Kadish and colleagues that recognizes three stages6:

However, correlation of tumor extent with prognosis has not been as accurate as the relationship of clear surgical margins.

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Clinically, the tumor appears to arise primarily at the superior or lateral aspect of the nasopharynx. The symptomatology often includes epistaxis, nasal and Eustachian tube obstruction, and eventual cranial nerve neuropathies (the fifth cranial nerve is most commonly involved). Histologically, these tumors are predominantly poorly differentiated carcinomas with a high propensity for metastatic regional spread, so that at the time of diagnosis, 50% of patients are expected to have regional disease. In the diagnostic evaluation, direct nasopharyngoscopy and biopsy, as well as a CT scan and MRI, provide for full assessment of the primary site. Irradiation is still considered a primary therapeutic modality for the nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the primary site and the regional lymph node draining area.7 The cure rate, however, varies tremendously depending on the histologic type of the tumor, stage of the disease, and subsequent therapy. The most frequent recurrence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is in the neck.8 Reirradiation of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma gives a 5-year cure rate of only 14%, with a high chance of radiation-induced complications. It is important prognostically to separate patients with metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the neck on the basis of their response to the primary irradiation. If metastatic neck nodes disappeared completely following irradiation, the recurrence rate was only 13%. If nodes persisted throughout the course of irradiation, the recurrence rate was 91%.

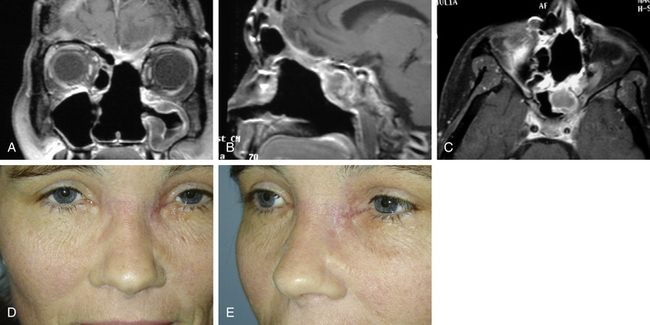

Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia is a progressive benign fibro-osseous lesion. Its natural growth is one of gradual expansion beyond its bony margins with concomitant displacement of surrounding soft tissue. It was first described by Lichtenstein in 1938.9 It may be placed into three categories on the basis of its clinical presentation. The monostotic form represents a localized disease to one osseous structure and is the most frequent form (up to 70%). A polyostotic form involves several bones but usually on the same side of the body. Here the frequency ranges from 30% to 50%. The third form is disseminated, in which numerous bones are involved, along with the possibility of extraskeletal developments such as skin pigmentation and precocious puberty. The incidence ranges from 3% to 30%. These individual clinical forms retain their categorization during the course of the disease and do not seem to change from, for example, the monostotic to the polyostotic form. Fibrous dysplasia is more common in females. In the head and neck region (0.5% of all head and neck tumors), it is the maxilla, frontal bone, mandible, and parietal and temporal bones that are most frequently involved. It is of interest that the progression of the disease is often limited after completion of skeletal maturation.10

Fibrous dysplasia can be treated by surgical resection when functional or esthetic deformity warrants it.11 Full preoperative evaluation should include CT scan, with and without contrast, in the axial and coronal planes with bone algorithms.

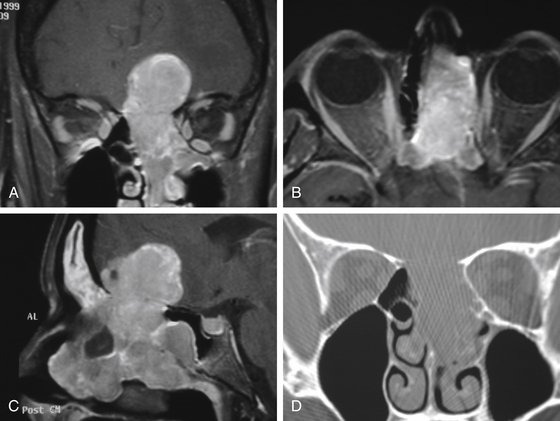

Juvenile Angiofibroma

Juvenile angiofibroma is a relatively rare tumor occurring primarily in adolescent boys. The site of origin of the tumor is thought to be the medial pterygoid region. Clinically, the tumor has the potential to involve the nasopharynx, nose, infratemporal fossa, sphenoid, orbit, middle cranial fossa, and cavernous sinus. There is a preferential growth through preformed anatomic fissures and foramina. The symptomatology is one of nasal obstruction with episodes of nasal hemorrhage that can be profound. The diagnostic evaluation usually consists of CT scan and MRI as well as angiography. The CT scan demonstrates classical widening of the pterygopalatine fossa. MRI is assuming a greater importance in the diagnosis of this tumor, its extent, as well as the degree of its vascularity. Angiography determines the blood supply to this lesion, which originates primarily in the external carotid system, usually the internal maxillary or the ascending pharyngeal artery. There may be additional blood supply from the internal carotid system. In the differential diagnosis, angiomatous polyp, pyogenic granuloma, and hemangioma are included in the benign group. Carcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and chordoma should be considered among the malignant tumors.12

The primary treatment has been surgical through a trans-facial or transpalatal approach, or, for extensive cases, craniofacial resection. Because of its vascularity and potential for a recurrence, a complete removal of this tumor should be attempted. The need for preoperative embolization can be determined at the time of the diagnostic angiography as well as from the appearance of tumor vascularity on the MRI scan. However, the potential complications from embolization must be considered and its advantage weighed against the potential risks. Recurrent tumors are usually treated again with surgery (if accessible) or irradiation. Hormonal therapy, originally thought to be beneficial, has not proved to be of significant value. Histologically, this tumor is composed of fibrous stroma and multiple vascular channels without a definite layer of muscularis in the vessel walls.13

Careful postoperative and long-term evaluation of patients with juvenile angiofibromas is important. MRI provides the best modality of clinical assessment. Harrison published a personal series of 44 patients treated by surgical removal in whom there was a 23% incidence of recurrence.14 These 10 patients with recurrent tumor received another operation. Of these 10 patients, 3 developed a second recurrence that was subsequently treated successfully with irradiation.

Chordomas

During the last 15 years, two new developments in the treatment of chordomas have occurred that may change the prognosis for cranial base chordomas. First, the advances in cranial base surgery have allowed a more complete resection of chordomas from difficult regions such as the clivus, the petrous apex, and the cavernous sinus. Second, irradiation with high-energy particles, such as proton beams (Bragg peak) or helium ions, has permitted the delivery of large amounts of radiation to a restricted area. The effects of both of these advances will require many years to evaluate, since chordomas are slow-growing tumors. The current management principle consists of surgical removal and postoperative irradiation.15–17

Chondrosarcoma

Since the bones of the cranial base are derived from a cartilaginous matrix through endochondral ossification, 60% to 70% of chondrosarcomas involve the cranial base skeleton. Such tumors may involve any area of the cranial base but have a predilection for the petrosphenoid synchondrosis.

Surgery

Craniofacial Resection

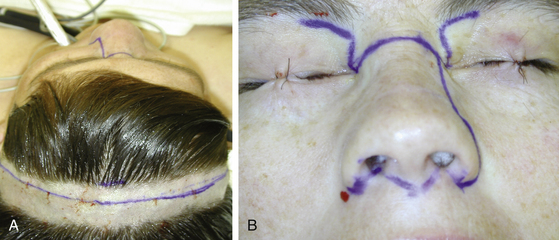

A bicoronal incision is used with removal of the craniofacial skeleton (Fig. 52-2). This incision outlines the distal end of the fronto-parietal scalp flap used for the exposure of the cranium. It is based inferiorly on supraorbital and supratrochlear vessels and laterally on branches of the superficial temporal arteries. It is a broad-based flap. It can include all the layers of the scalp, including the underlying pericranium, or it can be raised at the galeopericranial plane. Anterolateral extensions of this bicoronal incision, in front of each ear, permit reflection of the flap over the face (a greater rotational arch was achieved) and thus unhindered exposure to the cranium, the roof of the orbit, and both zygomatic arches. The frontalis branch of the facial nerve is preserved and reflected inferiorly in a fascial layer with the overlying scalp flap. The supraorbital neurovascular pedicle can be dissected out of its foramen or groove on each side and preserved. The nasion is well exposed, permitting access to both medial orbital walls. Loss of the sense of smell is always a consequence of this approach.

FIGURE 52-2 Incisions. A, Markings for bicoronal incision. B, Outline of midfacial and subcranial incisions.

In addition to the bicoronal scalp flap for superior exposure, inferior facial incisions are made (see Fig. 52-2). Several options are available, from a purely midline “face-splitting” incision (from the nasion through the upper lip) to a paramedian incision, a modification of a lateral rhinotomy incision. It is also possible to avoid direct facial skin incisions by performing what is referred to as a “degloving” procedure (a horizontal mucosal incision from one maxillary tuberosity to the other in the gingivolabial sulcus with elevation of all the soft tissues of the face including the nose). This approach, however, provides wide surgical access only at the level of the incision and significantly narrows at the skull base. Optimal visualization at the skull base is not achieved in the majority of cases. Also, reconstruction of the skull base, if needed, is difficult with this approach.

The “exposure osteotomies,” done in a zigzagging fashion, are performed with the intent to remove, as a free graft, the supraorbital bar, usually from one supraorbital nerve to the other. The facial bony segments are displaced following osteotomies, with the attached soft tissues. They may extend from one medial orbit across the nasion to the opposite orbit (usually to the level of the superior orbital nerve on the opposite side). If the orbital content is involved with the tumor, then it becomes part of the specimen. Before tumor extirpation, when needed, the ICA is isolated in the neck. The craniotomy used in this approach is a bifrontal craniotomy. After dural elevation from the anterior cranial fossa, tumor extent is appropriately assessed with preservation of as many uninvolved anatomic structures as possible including cranial nerves and the carotid artery.

Midfacial Split and Midfacial Translocation

Midfacial split provides a direct access and a unified surgical field at the central cranial base. It is performed utilizing bilateral facial osteotomies and soft-tissue mobilization. It extends in the sagittal plane from the anterior cranial fossa floor and sphenoid sinus to the level of C1. In the axial plane, the surgical reach extends between medial orbits superiorly, through the plane between V2 to the level of the palate. If the tumor demands wider exposure, an extended facial translocation with palatal split can be utilized.18

If further inferior exposure is needed, a tranoral-transmandibular approach can be selected.19 For more lateral access, an extended facial translocation18,20 can be added.

Facial Translocation

This approach to the skull base has undergone a significant evolution since its original description in 1989 and now comprises a system of approaches based on a principle of facial disassembly along embryonic planes of fusion.18,20,21 Due to its modular design, it permits great versatility of design and accommodates the surgical needs for limited as well as complex procedures at the skull base. The operative manipulation of cranial base anatomy and pathology, crucial for oncologic surgery, can be tailored with this system of approaches very precisely to a specific skull base tumor. Maximum preservation and functional and esthetic reconstruction of craniofacial anatomy is an integral part of this procedure.

The advantages of the facial translocation system of approaches include the following:

1. Facial anatomy has developed through the embryonic fusion of nasofrontal, maxillary, and mandibular processes. Normally, the fusion takes place in the midline or in the paramedian region, thus logically presenting optimal lines of “separation” of facial units for a surgical approach, permitting the least consequential displacement.

2. The primary blood supply to the “facial units” is through the external carotid system, which also has a lateral-to-medial direction of flow, thus ensuring viability of displaced surgical units.

3. The midface contains multiple “hollow” anatomic spaces (oronasal cavity, nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses) that facilitate the relative ease of surgical access to the central skull base.

4. Displacement of facial units for an approach to the cranial base offers much greater tolerance to postoperative surgical swelling, as opposed to similar displacement of the content of the neurocranium.

5. Reestablishment of the normal anatomy, following repositioning of the facial units during the reconstructive phase of surgery, has a high degree of functional as well as aesthetic achievement.

However, there are some disadvantages:

1. Contamination of the surgical wound with oropharyngeal bacterial flora.

2. The need for facial incisions with subsequent scar development.

3. Emotional considerations for the patient related to “surgical facial disassembly.”

4. The potential need for supplementary airway management (postoperative endotracheal intubation, temporary tracheostomy).

In the past, several surgeons worked on achieving additional oncologic exposure of the facial viscerocranium. Barbosa22 expanded exposure for the treatment of maxillary sinus cancer and Altemir23 did the same for the nasomaxillary area access.

Operative Technique

Modular craniofacial disassembly is the principle of the facial translocation approach to the skull base. It is based on the creation of composite facial units that are designed along key neurovascular anatomy and esthetic lines. The individual units merge into larger composites without compromising their function. It is possible to attach eponyms to the technical variations of facial translocation for ease of communication and comparison. Thus we can recognize “mini,” “standard,” “expanded” (vertically, medially, posteriorly), and “bilateral” facial translocation procedures.24 Complementary craniotomies or craniectomies are added to these approaches as necessary to assist with 3D tumor resection.

Extended facial translocation-medial and inferior includes the aforementioned procedure with an inferior extension via mandibular split. The lower lip split incision is performed in a zigzagging fashion to conform to the tension lines of the skin with a horizontal extension into the upper neck. Mandibular osteotomy is performed just medial to the mental foramen. Usually an interdental space is found wide enough to permit placement of a reciprocating saw for the osteotomy. This is performed in a step fashion, which then permits more stable reconstructive reapproximation of the bone. Before performing the osteotomy, it is wise to select an appropriate miniplate for eventual fixation, contour it to the mandible, and create drill holes. This maneuver assists in the reestablishment of a normal occlusion during reconstruction. This extended translocation procedure adds a significant inferior as well as upper cervical surgical access.

Reconstruction

The repair of any dural defect is performed with a pericranial graft harvested posterior to the bicoronal incision. In addition, a pericranial flap, based on supraorbital vessels, is utilized to enclose the cranial cavity and complete the separation of the cranial cavity from the extracranium. The reestablishment of external craniofacial bony continuity is done by replacing any skeleton displaced for exposure. Any surgical defect can be augmented with a split cranial bone graft or a titanium mesh. The most inferior portion of cranial base defects (floor of cranial fossae) is usually not bone grafted (Fig. 52-3). Further soft-tissue repair may include regional muscle transposition (temporalis) or free muscle–skin flap transfer (rectus abdominis or latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flaps).

Complications

Complications of a craniofacial resection can be categorized into fatal and nonfatal groups. Terz and colleagues reported an 11% fatal complication rate in their group of 28 patients. The three deaths in this series resulted from pulmonary embolus, brain injury, and tracheal abscess. In the nonfatal complication group, reported by the same investigators, there were several CSF leaks, meningitis, and osteomyelitis of the bone flap, for a 35% nonfatal complication rate.25

Careful attention to even minor details during the preoperative evaluation, the operation, and the postoperative period can often prevent major complications. For instance, when severe lower cranial nerve dysfunction is expected, a temporary tracheostomy and gastrostomy can prevent aspiration pneumonia and malnutrition. Since many of the initial postoperative problems are neurologic, cardiac, or respiratory, the patient should be observed in a unit with facilities for neurologic and cardiorespiratory intensive care. Because of the close collaboration among neurosurgery, otolaryngology, and plastic surgery, the incidence of postoperative problems following extensive cranial base surgery has been greatly reduced.26

Adjuvant Therapy

High-energy–focused radiation, with proton beams or helium ions, has been used to treat cranial base chordomas and chondrosarcomas with encouraging results.17

Although benign tumors such as meningiomas and neurilemmomas have been considered radioresistant, recent reports suggest that recurrent or residual tumors can be treated with external beam irradiation, reducing their growth rates.27 However, the deleterious effects of irradiation (carcinogenesis, normal tissue growth retardation) must be kept in mind.

For small benign lesions (<2.5 cm), such as meningiomas or acoustic neurilemmomas, stereotactically focused cobalt radiation has been used. Such “gamma knife” treatments appear to be effective in arresting the growth of tumors in many cases and offer an alternative to surgical treatment.28

In general, chemotherapy for cranial base tumors has not been successful. Tissue assay, performed on a sample of a removed tumor, may offer a potential for finding a more specific chemotherapy drug for each patient. In vitro drug testing on tumor cells is in its infancy and still not a perfect predictor of clinical response. However, treatment with assay “positive” drugs is reported to be more strongly associated with clinical response than is treatment with assay “negative” drugs (Weisenthal Cancer Group, “Functional Tumor Cell Profiling,” Huntington Beach, CA, http://www.weisenthalcancer.com/). We have obtained assays on several skull base tumors. Clinical conclusions cannot be drawn yet at this early stage; these findings could be used only as guidance to planning when chemotherapy option needs be considered.

Case 1: Chordoma of clivus. The tumor assay showed sensitivity to Cisplatin and Ifosfamide.

Case 2: Myxoid fibrosarcoma. The tumor assay showed sensitivity to Gemcitabine+Cisplatin, Gemcitabine+Melphan, Gemcitabine+Melphan+High dose of Tamoxifin.

Case 3: Meningioma, middle and infratemporal fossa. The tumor assay showed sensitivity to Taxol.

Case 4: Chordom of clivus. The tumor assay showed sensitivity to Docetaxel, Gemcitabine+Cisplatin, Gemcitabine+CP+High dose of Tamoxifin, Gemcitabine+Melphan+High dose of Tamoxifin, Vinorelbine+High dose of Tamoxifin.

Case 5: Synovial cell sarcoma of upper neck. The tumor assay showed sensitivity to Doxyrubicin, Gemcitabine+Melphan+High dose of Tamoxifin, Isosfamide.

Case 6: Squamous cell carcinoma, maxilla. The tumor assay showed sensitivity to Bleomycin, Cisplatin, Gemcitabine, Gemcitabine+Cisplatin, Docetaxel, Irinotecan+Cisplatin, Irinotecan+Cisplatin+High dose Tamoxifin, Topotecan+Cisplatin.

Case 5: Neuroendocrine carcinoma, ethmoid sinuses. The tumor assay showed sensitivity to Trimetrexate.

Case 6: Meningioma, orbit, middle, and infratemporal fossae. The tumor assay showed sensitivity to Extramusine, Decarbazine, and Taxanes.

Case 7: Myxoid fibrosarcoma, orbit, infratemporal fossa, skull base. Tumor assay showed sensitivity to Doxil, Doxorubicin, Epirubicin, Gemcittabine, Gemcitabine+Cisplatin, Gemcitabine(+Doxil+High dose of Tamoxifin, Gemcitabine+Isofosfamice(4HI), Gemcitabine+Melphan.

Choussy O., Ferron C., Védrine P.O., et al. Adenocarcinoma of ethmoid: a GETTEC retrospective multicenter study of 418 cases. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(3):437-443.

Chung W.Y., Pan D.H., Lee C.C., et al. Large vestibular schwannomas treated by gamma knife surgery: long-term outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(suppl):112-121.

Durante M., Loeffler J.S. Charged particles in radiation oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(1):37-43.

Ganly I., Patel S.G., Singh B., et al. Complications of craniofacial resection for malignant tumors of the skull base. Report of an International Collaborative Study. Head Neck. 27(6), 2005. 445-r51

Ganly I., Snehal G., Patel S.G., et al. Craniofacial resection for malignant paranasal sinus tumors: report of an International Collaborative Study. Head Neck. 2005;27(7):575-584.

Holzmann D., Reisch R., Krayenbühl N., et al. The transnasal transclival approach for clivus chordoma. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2010;53(5):211-217.

Janecka I.P. New reconstructive technologies in skull base surgery. Role of titanium mesh and porous polyethylene. Arch Otolaryngol. 2000;126:396-401.

Janecka I.P., Tiedemann K. Skull base surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1998.

Kadish S., Goodman M., Wang C.C. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a clinical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer. 1976;37:1571-1576.

Patel S.G., Singh B., Polluri A., et al. Craniofacial surgery for malignant skull base tumors: report of an international collaborative study. Cancer. 2003;98(6):1179-1187.

Roos D.E., Brophy B.P., Taylor J. Lessons from a 17-year radiosurgery experience at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Oct 30. [Epub ahead of print]

Sen C., Triana A.I., Berglind N., et al. Clival chordomas: clinical management, results, and complications in 71 patients. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(5):1059-1071.

Suárez C., Rodrigo J.P., Rinaldo A., et al. Current treatment options for recurrent nasopharyngeal cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267(12):1811-1824.

1. deVries E.J., Sekhar L.N., Janecka I.P., et al. Elective resection of the internal carotid artery without reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:960-966.

2. Thorup C., Sebbesen L., Danø H., et al. Carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses in Denmark 1995-2004. Acta Oncol. 2010;49(3):389-394.

3. Mendenhall W.M., Amdur R.J., Morris C.G., et al. Carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(5):899-906.

4. Choussy O., Ferron C., Védrine P.O., et al. Adenocarcinoma of ethmoid: a GETTEC retrospective multicenter study of 418 cases. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(3):437-443.

5. Berger L., Luc R. L’esthesioneuroepitheliome olfactif. Bull Assoc Fr Etude Cancer. 1924;13:410-420.

6. Kadish S., Goodman M., Wang C.C. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a clinical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer. 1976;37:1571-1576.

7. Rottey S., Madani I., Deron P., Van Belle S. Modern treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: current status and prospects. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011 Feb 16. [Epub ahead of print]

8. Suárez C., Rodrigo J.P., Rinaldo A., et al. Current treatment options for recurrent nasopharyngeal cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267(12):1811-1824.

9. Lichtenstein L. Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. Arch Surg. 1938;36:874-898.

10. Lei P., Bai H., Wang Y., Liu Q. Surgical treatment of skull fibrous dysplasia. Surg Neurol. 2009;72(suppl 1):S17-S20.

11. Eller R., Sillers M. Common fibro-osseous lesions of the paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2006;39(3):585-600.

12. Hyun D.W., Ryu J.H., Kim Y.S., et al. Treatment outcomes of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma according to surgical approach. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(1):69-73.

13. Stokes S.M., Castle J.T. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the nasal cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4(3):210-213.

14. Harrison D.F. The natural history, pathogenesis, and treatment of juvenile angiofibroma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:936-942.

15. Holzmann D., Reisch R., Krayenbühl N., et al. The transnasal transclival approach for clivus chordoma. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2010;53(5):211-217.

16. Sen C., Triana A.I., Berglind N., et al. Clival chordomas: clinical management, results, and complications in 71 patients. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(5):1059-1071.

17. Durante M., Loeffler J.S. Charged particles in radiation oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(1):37-43.

18. Janecka I.P., Tiedemann K. Skull base surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1998.

19. Liu J.K., Couldwell W.T., Apfelbaum R.I. Transoral approach and extended modification for lesions of the ventral foramen magnum and craniovertebral junction. Skull Base. 2008;18(3):151-166.

20. Janecka I.P. New reconstructive technologies in skull base surgery. Role of titanium mesh and porous polyethylene. Arch Otolaryngol. 2000;126:396-401.

21. Ganly I., Snehal G., Patel S.G., et al. Craniofacial resection for malignant paranasal sinus tumors: report of an international collaborative study. Head Neck. 2005;27(7):575-584.

22. Barbosa J. Surgery of extensive cancer of paranasal sinuses. Arch Otolaryngol. 1961;73:129-138.

23. Altemir F.H. Transfacial access to the retromaxillary area. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14:119-182.

24. Janecka I.P. Classification of facial translocation approach to the skull base. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112:579-585.

25. Ganly I., Patel S.G., Singh B., et al. Complications of craniofacial resection for malignant tumors of the skull base. Report of an international collaborative study. Head Neck. 2005;27(6):445-451.

26. Patel S.G., Singh B., Polluri A., et al. Craniofacial surgery for malignant skull base tumors: report of an international collaborative study. Cancer. 2003;98(6):1179-1187.

27. Chung W.Y., Pan D.H., Lee C.C., et al. Large vestibular schwannomas treated by gamma knife surgery: long-term outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(suppl):112-121.

28. Roos D.E., Brophy B.P., Taylor J. Lessons from a 17-year radiosurgery experience at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Oct 30. [Epub ahead of print]