Chapter 41 Anterior Lumbar Stabilization

INTRODUCTION

In the anterior reconstruction of the lumbar spine, there are several anatomical and biomechanical features unique to the lumbar spine.1 The important points are the large size and high weight-bearing demand of the lumbar vertebral bodies; greater mobility than the thoracic spine; lordotic curvature; restricted access to the lower lumbar spine because of the pelvic ring; and functional importance of the lumbar nerve roots compared with those of the thoracic spine. Although the upper lumbar segment (L1, L2 level) is considered to be the transitional zone between the rigid thoracic spine and the mobile lumbar spine, thoracolumbar instability is not a common problem after anterior-only reconstruction or circumferential decompression and stabilization at these levels. For L5 lesions, it is impossible to apply anterior stabilization because of the pelvic ring, which may be the case even in L4 lesions. In these cases, the stabilization should be performed with the posterior approach. The commonly used fixation site is the lateral surface of the vertebral body in the lumbar spine because of the midline location of the great vessels.

TECHNIQUE

PSOAS MUSCLE DISSECTION

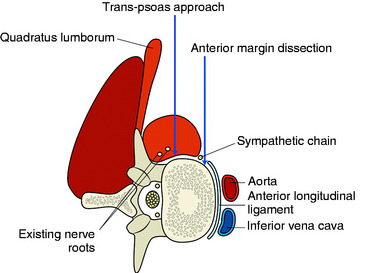

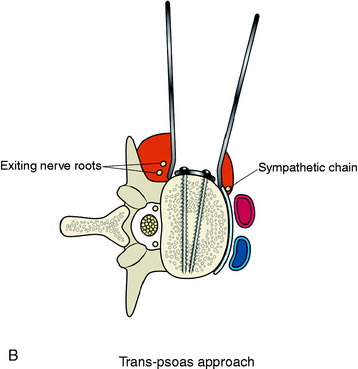

The stabilization procedure is carried out after retroperitoneal exposure of the lateral surface of the vertebral bodies. When the anterior instrument is implanted on the lateral surface of the lumbar vertebral body, the psoas muscle should be dissected. The psoas muscle covers the lateral surface of the vertebral body from the base of the transverse process to the lateral margin of the anterior longitudinal ligament (Fig. 41-1). The anatomical safe zone is the middle one-third of the width of the psoas muscle belly. In the anterior margin, the sympathetic chain lies underneath the psoas muscle and the exiting nerve roots are around the foramen. There are two ways to dissect the psoas muscle from the bony surface. First, the dissection starts from the anterior margin of the psoas muscle and continues to the foraminal side (see Fig. 41-1). Second, the dissection starts from the midline of the psoas muscle belly and retracted mediolateral side. During dissection of the psoas muscle, it is important not to injure the underlying extraforaminal nerve roots.

Course of Lumbar Nerve Root on Lateral Surface of the Lumbar Vertebral Body

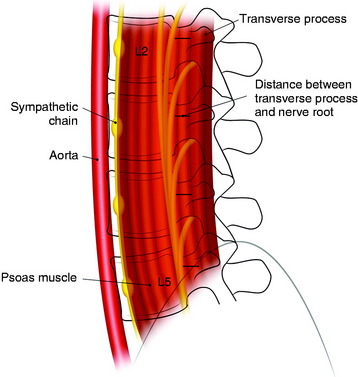

Each lumbar nerve root exits through the superior portion of the corresponding intervertebral foramen. At the beginning of the extraforaminal region, the exiting root runs down the lateral surface of the caudal pedicle, where it traverses the vertical leaf of the intertransverse ligament to take a ventrolateral direction and then join the descending lumbar trunk within the fascia of the posteromedial portion of the psoas muscle. The lumbar trunk runs downward vertically, as a compact cord-like bundle along the surface of the junctional area between the body and the pedicle of the lumbar spine, outside the foramen. The compact cord-like trunk is close to the most dorsolateral surface of the vertebral body and the intervertebral disc space. The width of the nerve trunk gradually increases in the lower lumbar level. The lumbar nerve trunk is topographically arranged dorsoventrally with the L5, L4, L3, and L2 nerve roots, in that order (Fig. 41-2).

The mean distances from the anterior border of the transverse process to the upper segment of the lumbar nerve root are estimated to be 5.1 to 6.4 mm (range 3–8 mm) at L2–5.2 There is little variation between the upper and lower levels. When surgeons dissect the psoas muscle, the expected location of the nerve roots is near the foramen.

Anterior Margin Dissection Method

The spine is exposed, following the anteromedial slope of the psoas muscle. The genitofemoral nerve, which passes along the psoas muscle, must be preserved. The anterolateral attachments of the psoas muscle are sharply dissected from the vertebral body. Care is used not to injure the underlying sympathetic chain and the segmental vessels. As in the vertebral bodies of other levels, the segmental vessels are arranged on the mid-portion of the vertebral body. On the axial view, the anterior margin of the psoas muscle corresponds to the anterior one-third of the vertebral body (see Fig. 41-1). When the medial half of the psoas muscle is swept away from the vertebral body, the posterior cortex of the vertebral body is visible (Fig. 41-3). For complete decompression, the pedicle should be palpated and the foramen should be recognized. The extraforaminal nerve roots are enclosed in the fascia of the muscle, so the possibility of nerve injury is small. However, because of the bulkiness of the psoas muscle, sufficient exposure of the lateral body surface may sometimes be difficult.

Trans-Psoas Dissection Method

When the psoas muscle is split longitudinally on the mid-portion of the muscle belly, the line of access corresponds to the posterior two-thirds of the vertebral body (Fig. 41-4). This approach route has a greater possibility of injuring the exiting nerve roots.

If the psoas is accessed correctly, the muscle fiber is dissected in the longitudinal plane.3 The dissection approaches to the vertebral body surface, and the muscle fascia is peeled off from the body surface. Once dissection through the psoas muscle is complete, the corpectomy is started.

IMPLANT APPLICATION

Anterior Stabilization at L1–3 Levels

At L1–3 levels, anterior decompression is performed via the lateral retroperitoneal approach.

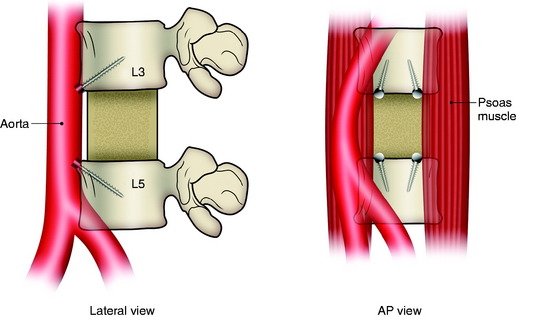

Anterior Stabilization at L4–5 Levels

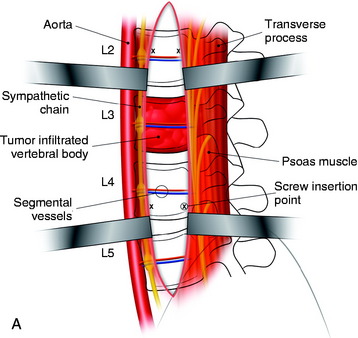

In cases of L4 body tumor, vertebrectomy is performed by the paramedian or lateral route. Decompression is possible with either route. However, rod or plate implantation may be difficult because the iliac vessels are located nearby. When the lateral approach is adopted, the pelvic ring can hinder the instrumentation. In these cases, small-diameter screws are used for the enforcement of the anchorage of the graft material (Fig. 41-5). The trajectory of the screw is not parallel to the endplate. When the paramedian approach is applied, the screw is directed 45 degrees to the adjacent disc space. In cases of L5 body tumor, the lateral approach is impossible. The approach is made with the anterior paramedian or midline route. A similar method can be used to apply screws in patients with L5 lesions.

TOTAL SPONDYLECTOMY AT LUMBAR SPINE (L4 MASS)

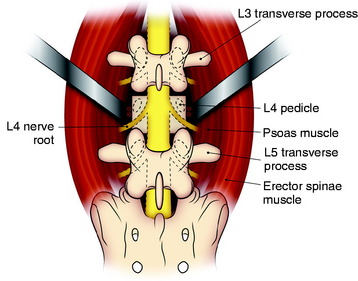

Posterior Procedure

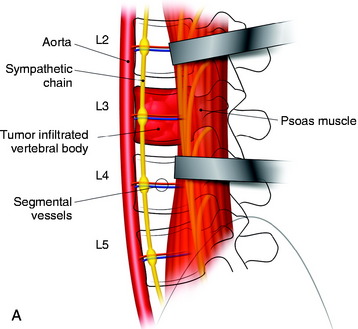

The operation is begun with the patient in the prone position. The abdomen is freely decompressed in a dependent position to minimize bleeding. In addition, all bony prominences are padded. A standard midline incision is performed with wide exposure of the bony elements at the L4 level as well as the levels above and below. The lateral extent of the exposure must include the tip of the transverse process (L3, L4, and L5). Using a combination of rongeurs, all bony posterior elements are removed. This includes the following elements of L4: spinous process, bilateral laminae, bilateral superior and inferior articular facets, bilateral pars interarticularis, and bilateral transverse processes. Beneath the ventrolateral surface of the L4 transverse process, the L3 nerve root passes down around the L4 vertebral body. Care should be taken not to injure the L3 nerve root. In addition, the pedicles are removed until they are flush with the L4 vertebral body. This is accomplished by drilling the center of the pedicle with a high-speed drill followed by use of rongeurs to remove the cortical shell of the pedicle. After all of the posterior bony elements are removed, the annulus fibrosis and the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral discs at the L3–4 and the L4–5 levels are removed with pituitary rongeurs. For an easier anterior procedure, it is useful to remove as much disc material as possible with the posterior approach. This disc removal must extend lateral and ventral to the exiting L3 nerve roots. Using large periosteal elevators, the psoas muscle just lateral to the L4 body is dissected away from the vertebral body as far ventrally as is safely possible (Fig. 41-6).4 Some surgeons suggest that the lumbar spondylectomy can be performed via the posterior approach only. This aggressive operation carries the risk of injury to the great vessels, which are not well visualized from the posterior route. Especially at the L4 level, the inferior vena cava is in direct contact with the vertebral body. Lesions at the L3 level and above may be safely treated with a purely posterior approach. An anterior staged operation should be considered for lower lumbar spondylectomy.

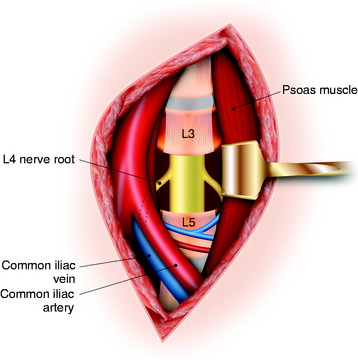

Anterior Procedure

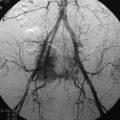

When the L4 level is confirmed, the intervertebral discs above and below are incised and removed. This disc excision is continued dorsally until the lateral-most aspects of the disc removal meet the defect created during the posterior procedure. When this is completed, the psoas muscles are dissected laterally from the lateral aspect of the vertebral body. This is relatively easily accomplished on the left side and is continued dorsally until the previous dissection is encountered. At this point, cotton patties placed ventral to the left L4 nerve root will be visible. Because of the location of the large arterial and venous structures in this area, dissection of the right side of the vertebral body is significantly more difficult. With gentle retraction of the iliac vessels toward the right side, periosteal dissectors are used to strip the psoas muscles from the right side of the vertebral body. Once again, the dissection is continued dorsally until the cotton patties ventral to the right L4 nerve root are identified. At this point, the vertebral body/tumor is lifted out of the operative field en bloc and is passed off the operative field. After the vertebrectomy, the previously placed cotton is removed. In addition, the ventral dura and exiting nerve roots are seen (Fig. 41-7). Anterior stabilization is accomplished using either a titanium cage or a femoral ring allograft. Autologous iliac crest bone graft is used to fill either the cage or the femoral ring.

BIOMECHANICAL ASPECTS ASSOCIATED WITH LUMBAR CORPECTOMY

The anterior instrumentation has provided less potential stability than the posterior and combined instrumentations in all motion directions. The anterior instrumentation, after vertebral body replacement, has shown greater motion than the intact spine, especially in axial torsion. Posterior instrumentation has provided greater rigidity than the anterior instrumentation, especially in flexion-extension. The combined instrumentation has provided superior rigidity in all directions compared with all other instrumentations.5

Case I

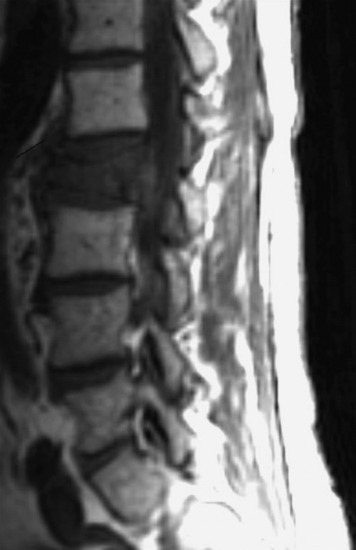

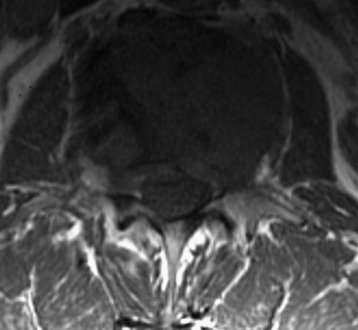

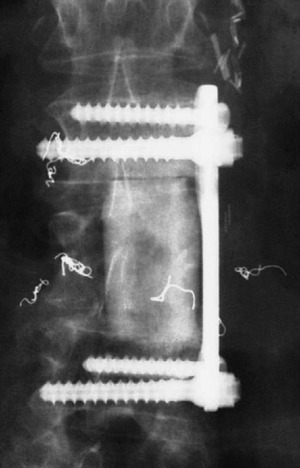

A 53-year-old male patient diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer was transferred to the hospital because of back pain and right anterior thigh pain. The pain was aggravated on sitting and standing. MRI showed a low signal lesion at the L2 vertebral body with mild posterior cortical erosion (Figs. 41-8 and 41-9). Definite instability was not observed. The operation was performed with a left retroperitoneal approach. The L2 vertebral body was removed totally and the ventral dura was decompressed. Anterior reconstruction was performed with a stackable carbon cage with a plate-screw system (Figs. 41-10 and 41-11).

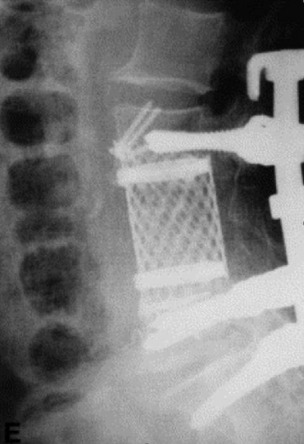

Case II

A 63-year-old woman presented with a 6-month history of low back and right lower extremity pain. This progressed to include right lower extremity weakness. MRI showed an L4 body mass with cauda equina compression (Fig. 41-12). A computed tomography-guided fine needle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of chordoma. An en bloc L4 vertebrectomy was performed. After posterior bony decompression, a plane could be developed between the ventrally located epidural tumor and the ventral surface of the thecal sac. The nerve roots of L3, L4, and L5 were visualized bilaterally and cotton patties were placed ventral to the neural elements (Fig. 41-13). A pedicle screw/hook/rod construct was used for stabilization, and fusion was performed with autologous iliac crest bone graft. Anterior L4 en bloc resection was then performed. After removal of the tumor/L4 vertebral body, cotton patties were removed and the intact L4 nerve roots were visualized. A titanium cage filled with autologous iliac bone graft was used for stabilization. For the supplemental fixation of the mesh, four small anterior screws were fixed (Fig. 41-14). An intraoperative complication of a small laceration of the left common iliac vein occurred. This was repaired primarily with 5-0 Prolene suture. In addition, transient left hip flexor weakness was detected postoperatively. At 6 months postoperatively, the hip flexor weakness had resolved and radiographic bony fusion was confirmed. At 30 months postoperatively, the patient is doing well with no neurological deficit and no evidence of tumor recurrence.