Chapter 27 Anterior Approaches to the Lumbar Spine

RETROPERITONEAL APPROACH WITH A PARAMEDIAN INCISION

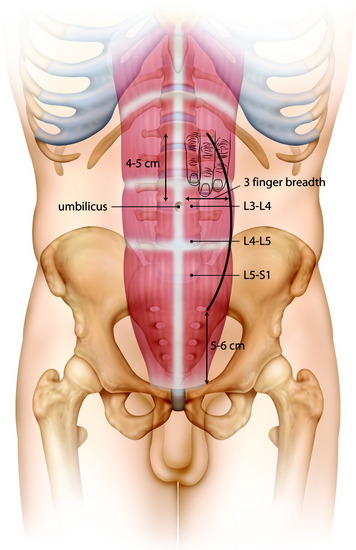

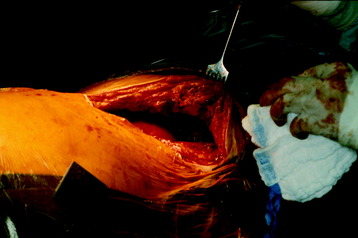

INCISION

The incision starts from 4–5 cm superior to the umbilicus, and reaches to 5–6 cm superior to the pubic symphysis (Fig. 27-1).

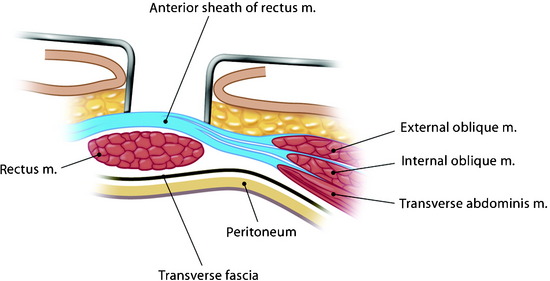

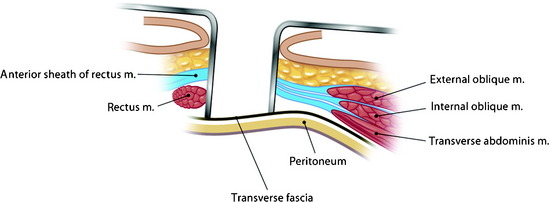

RECTUS MUSCLE INCISION

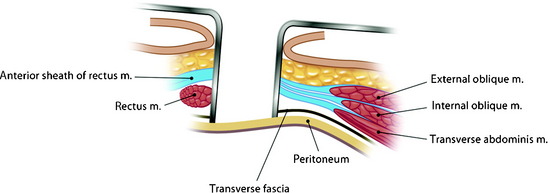

The anterior rectus sheath is incised (Figs. 27-2 and 27-3). During the incision, superficial epigastric vessels may be encountered and sacrificed. The rectus muscle is mobilized and retracted medially to expose the posterior sheath (Figs. 27-4 and 27-5). The inferior epigastric vessels lie between the abdominal wall muscles and the transversalis fascia.1 Because of their lateral position, they are rarely at risk during a midline approach but may be injured during a more lateral approach. Otherwise the rectus muscle can be split and the posterior sheath approached between the muscle fibers.

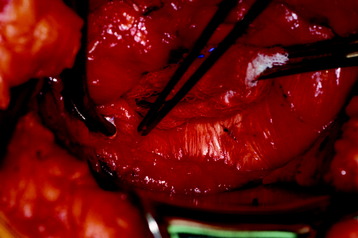

After the rectus muscle is swept away, the posterior rectus sheath is grasped and carefully incised to prevent cutting through the peritoneum (Figs. 27-6 and 27-7). The incision of the posterior sheath provides the entry into the retroperitoneal space. The retroperitoneal fat tissue lies between the posterior sheath and the peritoneum.

RETROPERITONEAL DISSECTION

Once the peritoneum is identified, it is swept off the abdominal wall with a blunt dissection (Figs. 27-8 and 27-9). An alternative method is to incise the fibers of the transversalis fascia below the arcuate line.2 The blunt dissection allows the surgeon to find the plane between the peritoneum and the transversalis fascia, which can be incised rostrally.

L5 BODY EXPOSURE

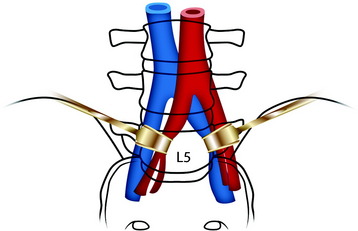

The L5 vertebral body is approached by mobilizing the great vessels at the bifurcation. Because the vascular anatomy at this level is somewhat varied, the surgeon should confirm the level of the L5–S1 disc space with an intraoperative x-ray. The bifurcation of the vena cava occurs lower than that of the aorta and is usually located above the L5–S1 disc space (Fig. 27-10).3 The aortic bifurcation usually is immediately anterior to the body of the L4 vertebrae, and the origin of the common iliac veins is observed mainly at the L5 body.

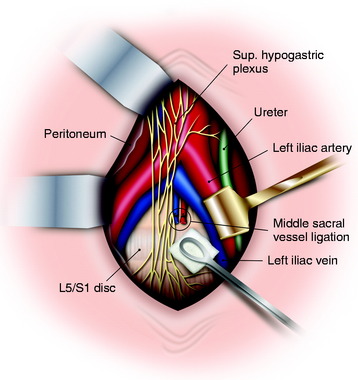

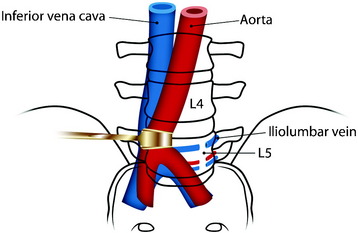

The vena cava bifurcation is to the right of the aorta, and the left common iliac vein passes through the aortic bifurcation. In the lower lumbar spine levels, care must be taken to identify all branches of the common iliac arteries and veins. The left common iliac vein, which is commonly injured, crosses at the L4–5 disc space. Ligating all branches will allow for the vessels to be mobilized to access the spine. The middle sacral artery and vein are routinely ligated during the operation to facilitate exposure. The sacral artery arises from the dorsal surface of the aorta just proximal to its bifurcation (Fig. 27-11). It is recommended that either vascular clamps or suture ligation are used to achieve this, and that the use of monopolar cautery is kept to a minimum. The use of electrocautery can cause damage to the superior hypogastric plexus, which in males can result in retrograde ejaculation.

VASCULAR MOBILIZATION

The dissection is carried anterior and medial to the left common iliac vessels. The middle sacral artery and vein may be taken with ligation. The left iliac vein needs to be widely mobilized to allow placement of the retractor against the left lateral edge of the spine.4

The L5 approach is easy to perform in patients with a high-lying bifurcation (Fig. 27-12). The bilateral retraction of common iliac vessels provides adequate exposure of the L5 vertebral body.

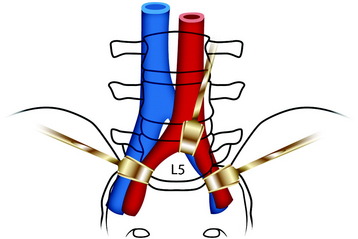

For patients with bifurcation on the L4–5 disc level, an upward retraction of the bifurcation point of great vessels is necessary (Fig. 27-13).

In cases of low-lying bifurcation, the retraction of the aorta and vena cava is accomplished from the left to the right side to expose the L5 vertebral body (Fig. 27-14). For the vena cava to be retracted, the iliolumbar vein and fifth lumbar vein should be searched out and ligated. The iliolumbar vein makes a tethering effect on the common iliac vein. For the L5 segmental vessels and iliolumbar vein to be found, the medial margin of the psoas muscle should be retracted to the lateral side. When the tumor infiltrates the vertebral body, the periosteum and anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) slacken, causing adhesion between the ALL and overlying vessels. The dissection of the vessels may be difficult.

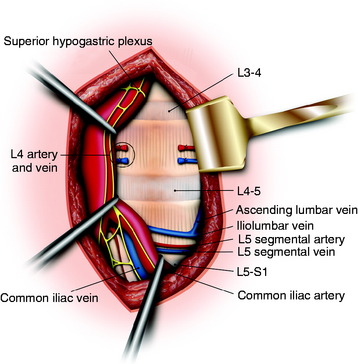

L4 BODY EXPOSURE

The great vessels and the superior hypogastric plexus are retracted in the medial direction (Figs. 27-15 to 27-17). For easy retraction of the great vessels, the L5 segmental vessels and iliolumbar vein may be ligated (see Fig. 27-15).

Before the L4 corpectomy is performed, the adjacent discs are removed. The L3–4 intervertebral disc and the L4–5 intervertebral disc are removed and the L4 vertebral body is approached. With the monopolar coagulator, the ALL is coagulated and resected (see Fig. 27-16). Vertebral body removal is performed with a punch and drill. After the posterior cortex of the vertebral body is removed, the ventral dura is seen. From the dural sac, the origin of the nerve root can be seen.

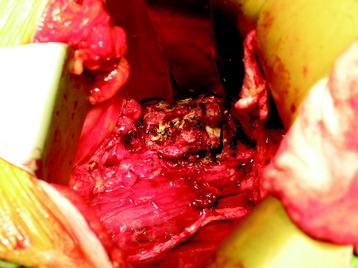

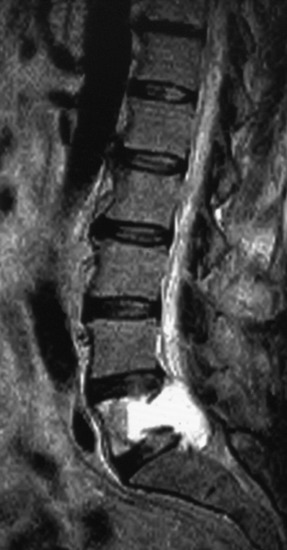

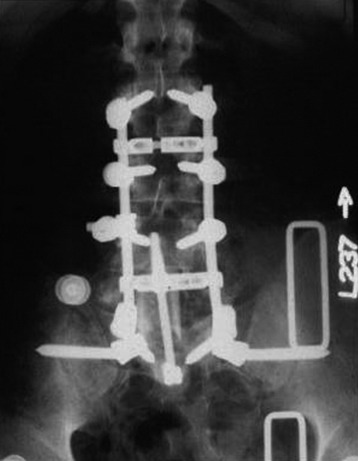

CASE ILLUSTRATION

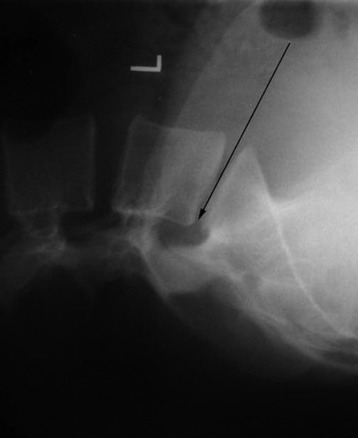

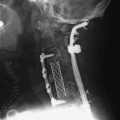

This patient presented with low back pain with right leg pain. The magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed a hyperintense lesion at L5 with posterior cortical destruction (Figs. 27-18 and 27-19). The L5 corpectomy was performed via an anterior paramedian extraperitoneal approach, and a femoral allograft was inserted. Anterior fixation was performed with a screw-and-rod system between L4 and S1. Long-segment screw fixation was added via the posterior approach from the L2 to S2 level (Figs. 27-20 and 27-21).

RETROPERITONEAL APPROACH WITH FLANK INCISION

The lateral retroperitoneal approach to the L2–5 vertebral bodies accomplishes the following5:

SKIN INCISION

The skin incision should be centered between the lowest rib and the iliac crest, with minor adjustments made depending on the appropriate level (Fig. 27-22). The incision should be S-shaped with the abdominal aspect curving inferiorly as it approaches the midline and the posterior aspect curving gently cephalad. This is done to avoid cutting the rectus abdominis ventrally and the quadratus lumborum dorsally. The incision is extended down to the external oblique fascia.

MUSCLE INCISION

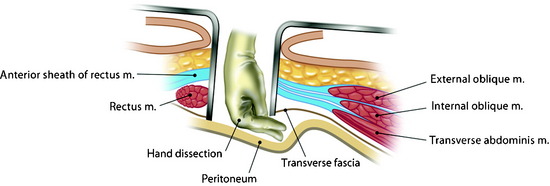

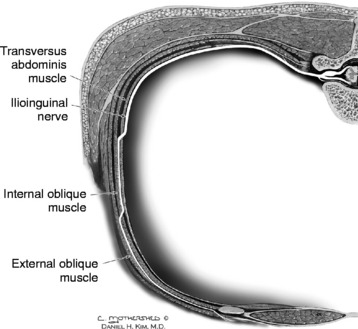

For more common muscle cutting, the external and internal obliques are approached, and the transversus abdominis is incised. The rectus abdominis muscle should be spared at the medial aspect of the incision. On incising the transversus abdominis, the loose areolar tissue of the retroperitoneal space is visualized (Fig. 27-23).

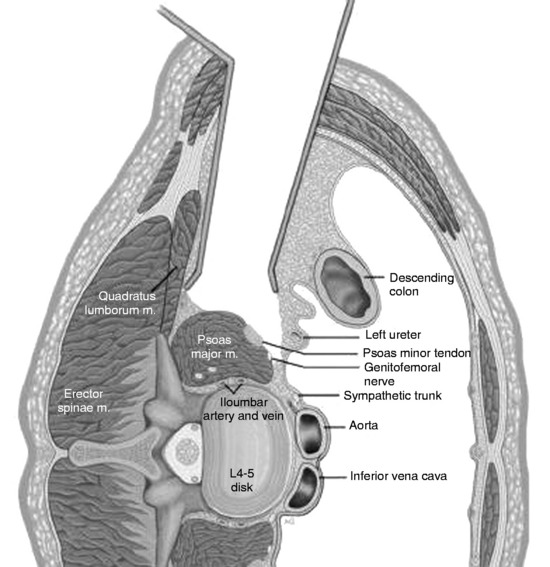

RETROPERITONEAL DISSECTION

The thin translucent peritoneum can be seen and the plane is developed with a blunt dissection. The peritoneum is gently swept off the posterior abdominal walls and the abdominal surface of the diaphragm. The abdominal contents, which are being held by the peritoneum, are then retracted medially. The kidney, ureter, and perinephric fat are located in the retroperitoneal space (Fig. 27-24). The kidney is surrounded by a collection of fat known as the perirenal fat. The connective tissue ventral and dorsal to the kidney condenses to become the renal fascia, which envelops the kidney and surrounds the perirenal fat. There is another collection of fat surrounding this fascia called the pararenal fat. When mobilizing the kidney medially, one should retract the renal fascia and take care not to enter into the pararenal fat. Retroperitoneal procedures in general offer several potential advantages over transperitoneal approaches to the lumbar spine. Retroperitoneal approaches obviate the risk of small bowel obstruction or postoperative intraperitoneal adhesions. Because the autonomic plexus is not dissected, there is a reduced risk of retrograde ejaculation as compared with the transperitoneal approach. In addition, the lateral decubitus position facilitates exposure of the lumbar spine, as gravity helps in pulling the abdominal contents anteriorly.

PSOAS MUSCLE DISSECTION

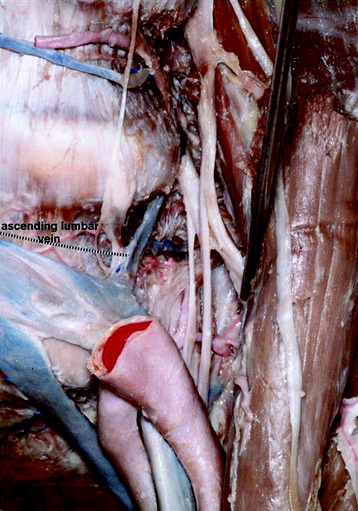

The psoas muscle is identified and is the key to identifying the spine. The medial aspect of the psoas is attached to the spine, and the vertebral bodies and disc spaces can be palpated.6 The genitofemoral nerve is usually visualized on the surface of the psoas muscle. Once a disc space is identified, the psoas muscle is dissected off the vertebral body by incising its attachments to the fibrous arcades that form its origin on the vertebral body. In the upper lumbar spine segments, the psoas will need to be reflected off the anterior portion of the vertebral body. This can be accomplished with a Cobb elevator and should be started at the midline and carried posteriorly. Once the psoas has been retracted, the anterior spine is visualized along with the segmental vessels and the sympathetic trunk. Less psoas dissection will be necessary in the lower lumbar spine. The structures that will need to be identified include the common iliac veins/arteries and all branches (Fig. 27-25). This includes the iliolumbar vein and ascending lumbar vein. Lumbar nerve roots are combined and form a plexus beneath the psoas muscle.

Alternatively, the vertebral body can be accessed through the psoas muscle belly.7 The dissection is carried out in a longitudinal fashion in line with the muscle fibers and through the anterior one-third of the psoas muscle. The intervertebral disc space often can be palpated through the psoas muscle and is exposed first. The respective mid-portions of the adjacent vertebral bodies are then exposed. The lumbar segmental vessels are ligated and divided. The segmental vessels are dissected from the underlying bone and elevated with a right-angled clamp. It is important to use two vascular clips on the high-pressure side of the vessels; the vessels are divided with scissors. The segmental vessels are ligated and divided in the anterior half of the vertebral body to allow maximum possible collateral circulation to the neural foramen and spinal cord. The disc space is incised using a sharp blade. The curettes and pituitary rongeurs are used to perform a complete discectomy. The adjacent discectomies are finished and a corpectomy is performed (Fig. 27-26). Some patients may experience groin/thigh discomfort after surgery. These symptoms are consistent with the cutaneous innervation of the genitofemoral nerve. However, these symptoms resolve within 1 month or so.

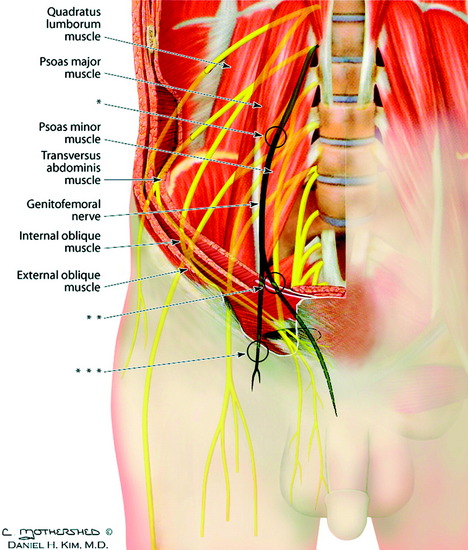

The genitofemoral nerve is a mixed nerve with a preponderance of sensory fibers.8 Its main root originates from L2 and is constantly present, whereas the slender and inconsistently present accessory root originates from the anterior branch of the L1 nerve. The genitofemoral nerve travels obliquely between the two muscle bellies of the psoas muscle and perforates the psoas major at the level of the intervertebral disc lying between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae (Fig. 27-27). It descends along the anterior surface of the psoas muscle. As the nerve passes through the lumbar region, it crosses behind the ureter. It takes a straight inferior and somewhat caudal course along with the iliac vessels in the region of the internal iliac fossa. Slightly posterior to and at a variable distance above the inguinal ligament, it divides into its two terminal branches, the genital and femoral branches. The genital branch crosses the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles (see Fig. 27-27) and enters the inguinal canal through the internal inguinal ring. The femoral branch is a cutaneous nerve, and branches of it descend and follow the external iliac artery, remaining lateral to it. The femoral branch continues behind the inguinal ligament and through the fascia lata (see Fig. 27-27) into the femoral sheath, lateral to the femoral artery. Visualization and protection of the genitofemoral nerve should prevent permanent paresthesias in the anterior thigh. If the dissection starts from the anterior one-third of the psoas muscle, genitofemoral nerve palsy can be reduced.

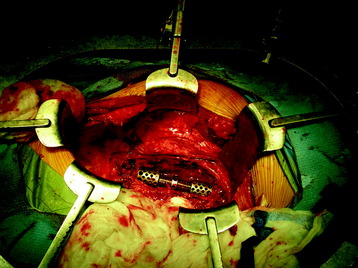

CASE ILLUSTRATION

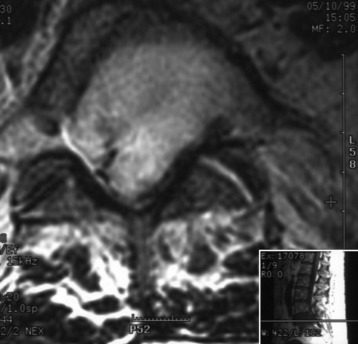

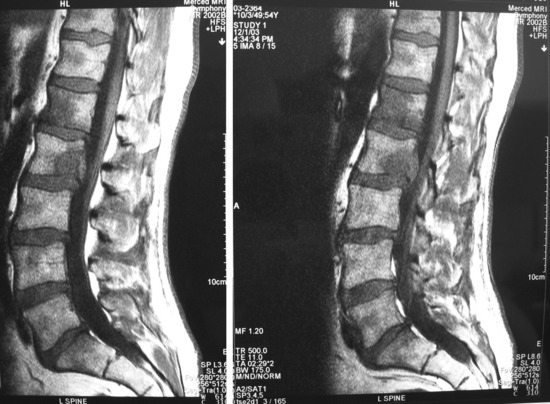

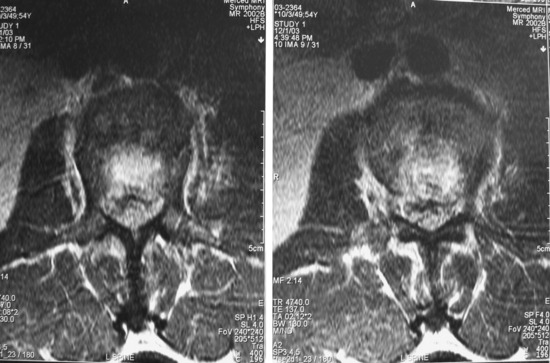

A 54-year-old man complained of progressive low back pain for 6 to 7 months.

The pain was constant during the day and night. Nonoperative treatment was attempted but failed. A tingling sensation developed in the right groin and right thigh. An MRI was taken at about the lumbosacral spine level. On the MRI, low signal lesions were found at the L1–2 vertebral body (Fig. 27-28). On axial images, the lesion was seen to break the posterior cortical margin (Fig. 27-29). The operation was performed circumferentially.

The anterior retroperitoneal approach was performed with a left flank incision. L1 and L2 vertebral bodies were removed, and a vertebral body replacement cage was inserted. Anterior instrumentation was performed with a rod-and-screw system. In addition, posterior stabilization was applied with a pedicle screw system (Fig. 27-30). Posterior instrumentation was performed three levels above and four levels below.

TRANSPERITONEAL APPROACH TO THE LUMBOSACRAL JUNCTION: L4–S1

The transperitoneal approach generally is used for approaches to the L5 vertebral body and the sacrum.9 It also is used when the retroperitoneal space has been injured from prior surgery or radiation therapy. The disadvantages of the transperitoneal approach are the risk of peritoneal cavity contamination by tumor, difficulty with preexisting adhesions, the need for a preoperative bowel preparation resulting in a greater risk of visceral injury, the need for greater mobilization of the great vessels, less extensive exposure of the superior lumbar spine, and the increased risk of an ileus postoperatively.10

The transperitoneal approach to the lumbar spine involves three stages of dissection. The superficial stage involves the dissection from the skin to the peritoneum. The intraperitoneal stage traverses the peritoneal cavity and involves packing or retracting the viscera out of the way. The retroperitoneal stage consists of mobilizing the retroperitoneal structures, including the great vessels (aorta, vena cava, or common iliac vessels), ureters, and presacral plexus.11

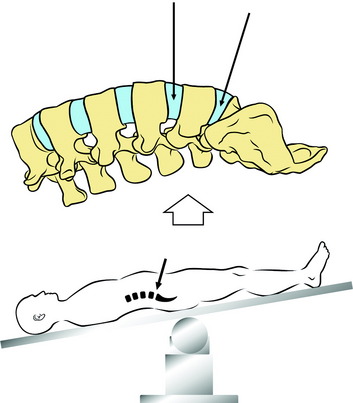

POSITIONING

Routine bowel preparation is required at this point. The patient is placed supine with Trendelenburg positioning used to push the intra-abdominal contents superiorly away from the surgical field (Figs. 27-31 and 27-32).12 A sacral bolster is used for the maintenance of the lumbar lordotic curve. The patient’s arms are in an abducted or crossed position.

SUPERFICIAL STAGE

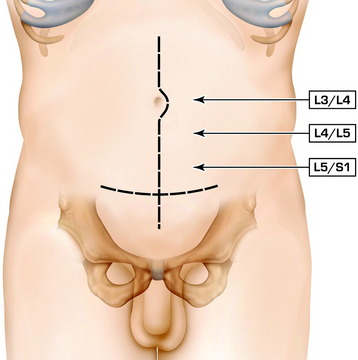

SKIN INCISION

To expose L5–S1, an incision is made between the symphysis pubis and umbilicus. A slightly higher incision is made for L4–5. The transperitoneal approach to the lumbar spine is generally performed through either a midline or a Pfannenstiel incision. A longitudinal midline incision is the most extensive way to approach the lower lumbar spine and lumbosacral junction (Fig. 27-33). If the approach is limited to the L5–S1 level, a transverse Pfannenstiel incision is useful and more cosmetic than the midline extensile incision. With the Pfannenstiel incision, care must be taken to prevent injury to the inferior epigastric vessels.

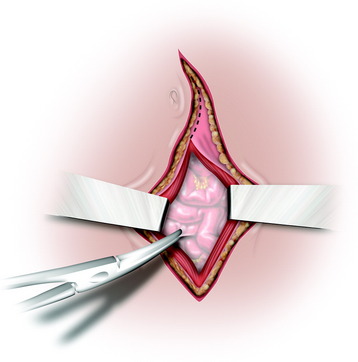

Incision Of The Deep Layers

For the open transperitoneal approach, the incision should be carried down in the midline between the abdominal musculature along the linea alba to prevent damage to or denervation of the rectus muscles, whose nerve supply is derived from the segmental branches of the seventh through 12th intercostal nerves (Fig. 27-34). The rectus muscle is retracted laterally to prevent denervating the muscle. A rectus splitting approach is favored rather than rectus sacrificing.

After dissection of the subcutaneous tissue, the linea alba is exposed and transected in the midline with scissors (Fig. 27-35).

INTRAPERITONEAL STAGE

INTRAPERITONEAL STAGE

Intraperitoneal Dissection

The viscera are packed off with moist pads, and a self-retaining retractor system is placed.

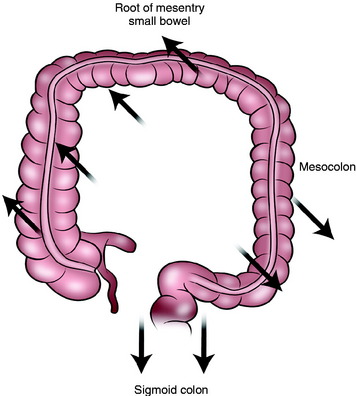

The greater omentum, small bowel, and the mesenteric root are retracted rostrally.13

The mesocolon is retracted laterally (Fig. 27-38). The sigmoid colon is retracted caudally. The ureter is identified to cross the brim of the pelvis just beyond the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, being adherent to the peritoneum along the psoas muscle.

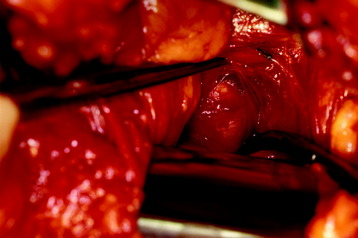

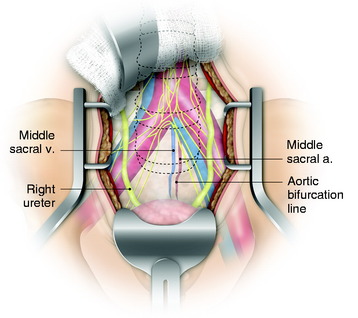

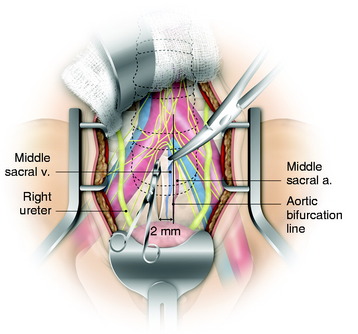

The posterior layer of the peritoneum overlying the great vessels is carefully identified and incised (Fig. 27-39). The posterior peritoneum overlying the lumbosacral junction is identified and gently elevated using forceps and opened with Metzenbaum scissors. It is opened in a linear fashion 2 cm to the right of the midline to prevent inadvertent injury to the middle sacral artery before ligation (Fig. 27-40). Great care should be given to identify the ureter crossing the right external iliac artery. The peritoneum is incised sufficiently to allow for it to be elevated laterally over the bifurcation.

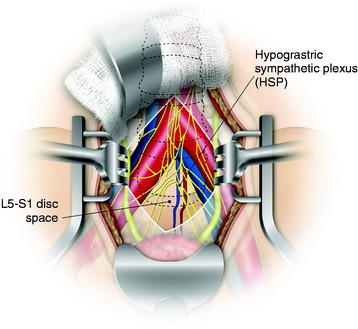

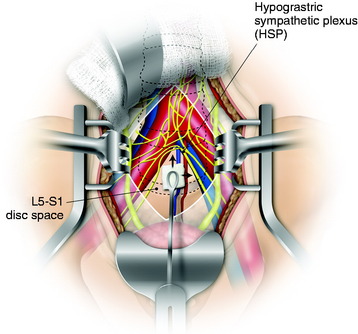

RETROPERITONEAL STAGE

The retroperitoneal vessels and the superior hypogastric plexus are covered by a layer of fat and connective tissue (Fig. 27-41). This layer is bluntly opened over the right common iliac artery to the right of the midline. Even though the retroperitoneal tissue in this area is predominantly fat, the blunt technique will result in mobilization of any autonomic nerves and largely obviate the need for their division (Fig. 27-42). The superior hypogastric plexus of nerves is located in this soft tissue, and care must be taken in mobilizing these nerves off L5 and the area of the bifurcation.14 The superior hypogastric plexus is found bilaterally over the middle sacral artery. To minimize damage to this structure, which can result in genitourinary dysfunction, electrocautery should be avoided. The superior hypogastric plexus is swept away with a blunt dissection from the underlying great vessels. Dissection starts from over the right common iliac artery, proceeding to the upward and midline direction, which discloses the whole course of the middle sacral artery and vein (Fig. 27-42). The sacral artery is seen from the dorsal surface of the aorta just proximal to its bifurcation. These can be tethered to the annulus by inflammatory adhesions and must be carefully mobilized. The median sacral vessels are isolated, clipped, and divided. The left common iliac vein usually overlies the left part of the annulus. This usually can be dissected bluntly from the annulus. Occasionally, a few fibers of adherent tissue must be divided to facilitate this mobilization. The right iliac vein is rarely in the way and does not usually require significant mobilization.