Chapter 18 Anterior Approaches to the Craniovertebral Junction

INTRODUCTION

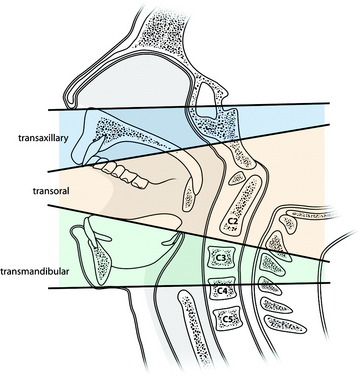

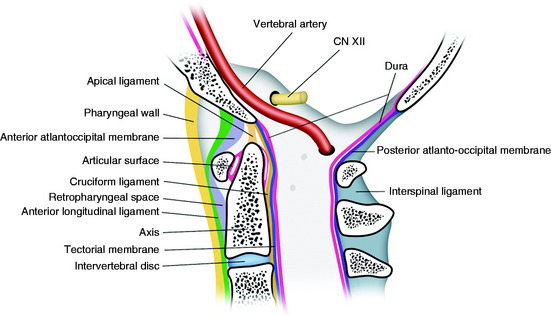

Anterior approaches are considered the best means for removing ventral lesions at the craniovertebral junction (CVJ). These approaches provide direct access to the lesions and allow for the graft to be positioned after decompression. These approaches can be used to reach tumors of the clivus and upper cervical spines. They can be classified as the transoral transpharyngeal approach, the translabiomandibular transpharyngeal approach, and the transoral approach with maxillotomies according to the cephalocaudal extent of the exposure (Fig. 18-1).1 The standard transoral procedure allows the exposure of the midline between the C1 and the C2–3 intervertebral disc.2,3 The exposure may be extended in a cephalad direction by dividing the soft and hard palate to allow access to the foramen magnum and the lower clivus and even farther to the sphenoid sinus with an extended open door maxillotomy.

However, this procedure has limitations for laterally extending tumors, may increase the risk of meningitis, and lacks vertebral artery control. The transoral approach is contraindicated when there is significant dural invasion of tumor mass or when large dural resection is required.4

TRANSORAL TRANSPHARYNGEAL APPROACH TO THE CRANIOVERTEBRAL JUNCTION2

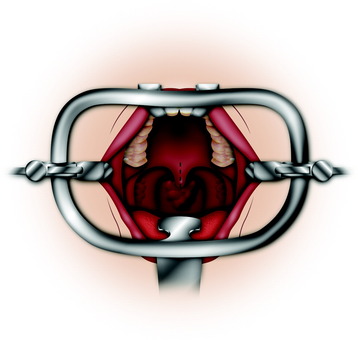

This approach exposes the inferior one-third of the clivus down to the C2 vertebral body. The entrance to the oral cavity must provide a working distance of 2.5–3 cm between the upper and lower teeth.2 A tracheostomy is performed when the operation involves the high nasopharynx and the craniocervical junction. An operation at the atlas and axis levels may not require a tracheostomy. The patient is placed supine with the neck in slight extension. The mouth is kept open with a Dingman or Crockard retractor.

SOFT PALATE INCISION

The soft palate can be split at the midline to extend superior exposure (Figs. 18-2 and 18-3). The incision should be full thickness and extended to the junction of the hard and soft palates. If the lesion is located in the lower clivus, simply dividing the soft palate may be sufficient, but if the upper clivus needs to be exposed, removal of the bony plate is required.

PHARYNGEAL WALL INCISION

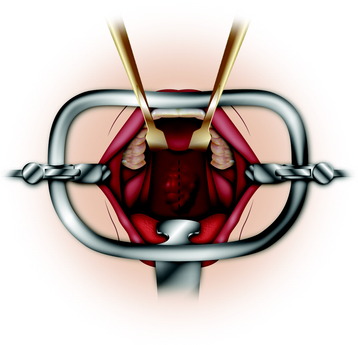

The anterior C1 arch can be palpated through the posterior pharyngeal wall and verified with fluoroscopy. An initial incision is made on the midline through the mucosa of the posterior pharynx (Fig. 18-4). The anatomical landmark for the midline is the anterior tubercle of C1.

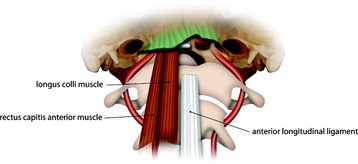

The mucosa layer is dissected separately from the prevertebral fascia investing the underlying muscle layer (Fig. 18-5). The longus capitis and longus colli muscles are subperiosteally elevated, and the arch of C1 is identified.

The longus and longus capitis muscles are originated from the basiocciput, and the origin site should be stripped off for exposure of the lower clivus (Fig. 18-6). Beneath the muscle layer, the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) is firmly attached to vertebral body surface. The ALL has a pointed attachment to the anterior tubercle of the atlas that widens as it descends to its insertion at the sacrum.5 The ALL is divided with electrocautery and reflected with a sharp dissect to complete the exposure of the C1 arch.

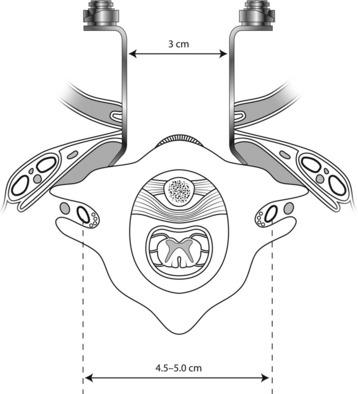

The mucoperiosteal layers are spread with a self-retaining retractor to a maximum of 1.5 cm to either side (Fig. 18-7). The anatomical landmark of the lateral limit of the exposure is the pharyngeal recess. Usually the maximal transverse exposure is provided at the level of the C1 arch, and the transverse length of exposure is lessened at the C2 level.

TUMOR REMOVAL

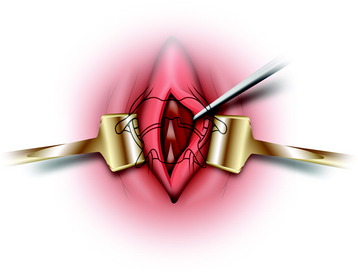

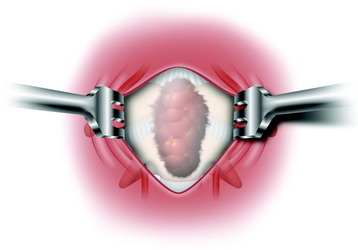

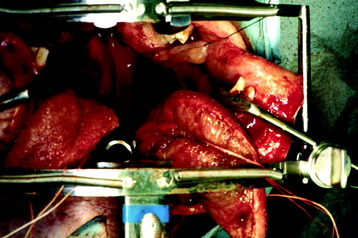

The tumor is resected intralesionally, being debulked from the central to peripheral portion. In the case of chordoma, the mass is layered off from the inside out. Its margin is defined from the normal tissue. Tumors arising in this region are quite soft and well-circumscribed and may well be removed with relative ease using rongeurs, an ultrasonic aspirator, or a laser (Fig. 18-8).

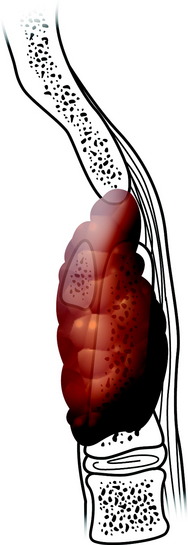

The tectorial membrane acts as a barrier to the epidural spread of bone lesions (Fig. 18-9).

The apical and alar ligaments are identified at the apex of the odontoid and divided using electrocautery. The remnant of the odontoid can be removed with a 1- or 2-mm Kerrison punch. The dense tectorial membrane and cruciate ligament, which lie posterior to the dens, protect the dura from injury (Fig. 18-10).

CASE ILLUSTRATION

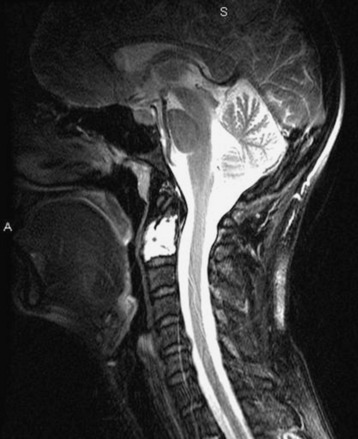

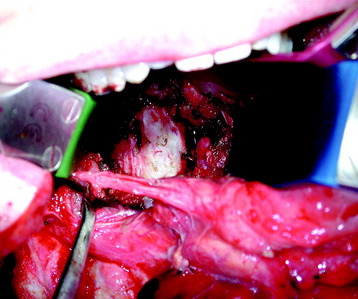

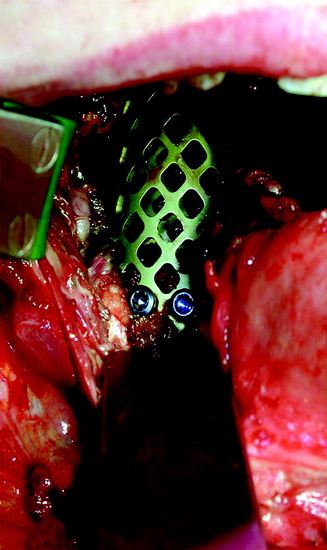

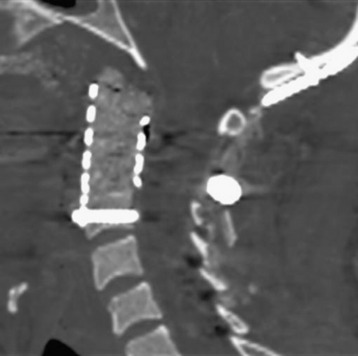

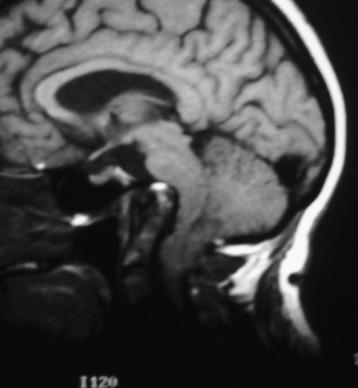

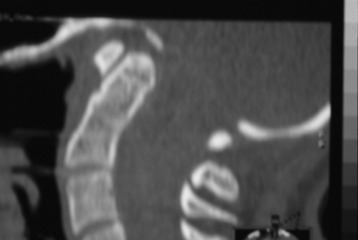

A 40-year-old man presented with posterior neck pain. The patient’s magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed a hyper-intense mass at the C2 vertebral body with mild cortical destruction (Fig. 18-12). Transoral resection of the C2 mass was performed. After the C2 body was removed, the ventral dura was seen (Fig. 18-13). The titanium mesh graft was inserted into the corpectomy site (Fig. 18-14). A postoperative computed tomography (CT) scan shows the insertion of the anterior lower screw through the mesh plate. The graft was between the C1 arch and C3 vertebral body (Fig. 18-15).

MEDIAN LABIO-MANDIBULO-GLOSSOTOMY3

INCISION

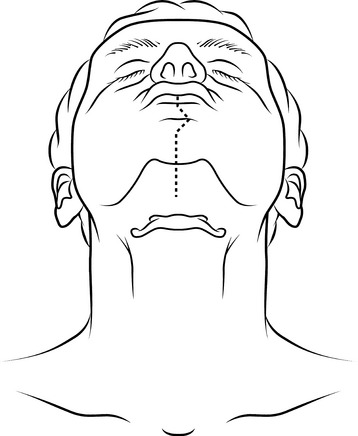

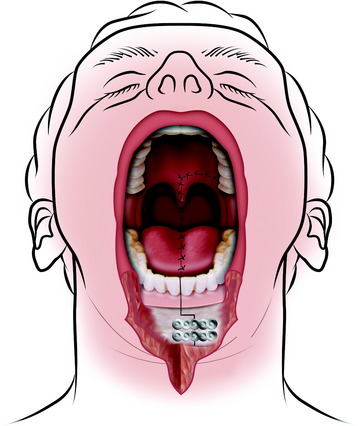

A preoperative confirmation of airway should be made with the tracheostomy. This approach, originally described by Trotter, requires a lip- and chin-splitting incision (Fig. 18-16). A simple vertical incision should be made cleanly through the red lip. From the vermilion border, the vertical incision is continued to the chin button. It is carried around the button of the chin back to the midline.2 Incision is extended vertically into the submentum. A mucosal incision is made at the alveolar margin under the lower lip.1 Neck incision is essential and allows maximal lateral retraction of the jaw. The symphysis of the mandible then is exposed between the mental foramina.

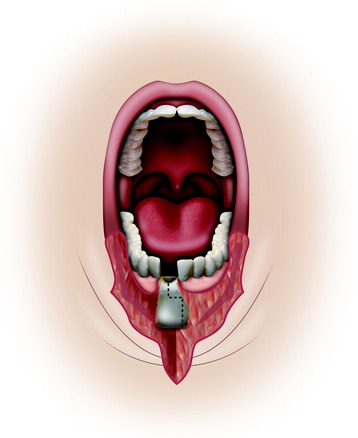

MANDIBLE SPLITTING

Before mandible splitting, mini-plates should be pre-bent and fitted, and screw holes should be predrilled. A stair-step or vertical mandibulotomy is performed, splitting the mandible between the two central incisors (Fig. 18-17). Care should be taken to avoid injury to the lamina dura of the teeth (Fig. 18-18). Dental extraction is rarely necessary. When vertical mandibulotomy is performed, the straight line is situated anteriorly to the V3 foramen of the symphysis. With stair-step mandibulotomy, bone contact surface is increased and a more stable construct can be gained at the time of plating.

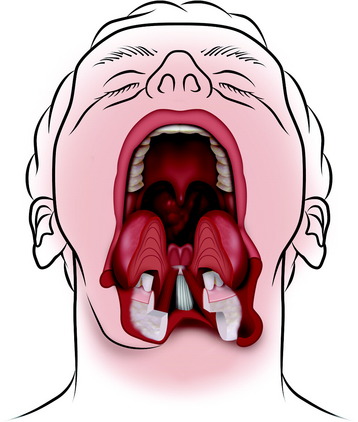

GLOSSOTOMY

The anterior floor of the mouth then is incised. This approach is called a midline glossotomy. The tongue is split along its midline raphe, exposing the hyoid bone and vallecula (Figs. 18-19 and 18-20). This allows excellent exposure and minimizes the risk to the hypoglossal and lingual nerves.1 Alternatively, the floor-of-mouth incision can be continued posteriorly in the gingivolingual sulcus toward the anterior tonsillar pillar. It is important to leave an adequate cuff of mucosa on the alveolus to allow watertight closure at the termination of the procedure. Removal of the submandibular gland is not always necessary but does help in the identification of the lingual and hypoglossal nerves, thereby decreasing their risk of injury. The mylohyoid sling is divided along its entire length, allowing lateral distraction of the hemimandible. The anterior tonsillar pillar incision is deepened, and the outer surface of the superior constrictor muscle is identified. It is important not to injure the internal carotid artery when developing this plane. The pharynx is elevated off the prevertebral fascia. The distal end of the eustachian tube and the tensor veli palatini are divided, providing adequate exposure of the clivus. The pharynx is removed from the pharyngeal tubercle, allowing it to be retracted laterally.

EXPOSURE OF THE PHARYNGEAL WALL

The pharyngeal wall is exposed with the application of the self-retaining retractor. Great care is taken to not injure the submandibular duct and over-retract the mandible (Fig. 18-21). The longitudinal incision on the midline is performed to expose the upper cervical spine. The mandible resection provides extensive exposure of the surgical field to C4.6 For the exposure of the C4 vertebral body, the epiglottis and vocal cord should be retracted.

CLOSURE

Rigid internal fixation with plates is used for mandible fixation. The plates are always adapted to the mandible before a through-and-through bone cut (Fig. 18-22). Careful closure of the labial incision is important. Exact alignment of the vermilion border is necessary. The lip is closed in layers, taking care to repair the orbicularis oris muscle. The chin also must be closed in layers, with the deep sutures carefully reapproximating the muscle and subcutaneous tissues. The suture of the tongue closure is performed in at least two layers (Fig. 18-23).

CASE ILLUSTRATION

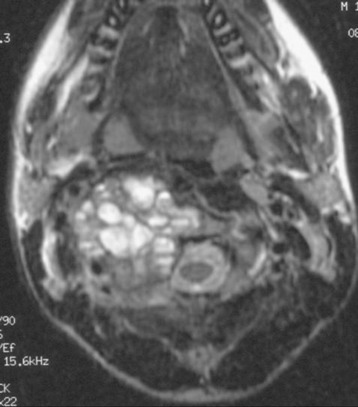

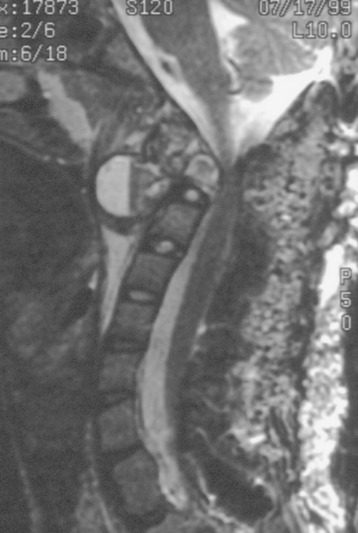

A 14-year-old boy presented with progressive worsening headache and neck pain.

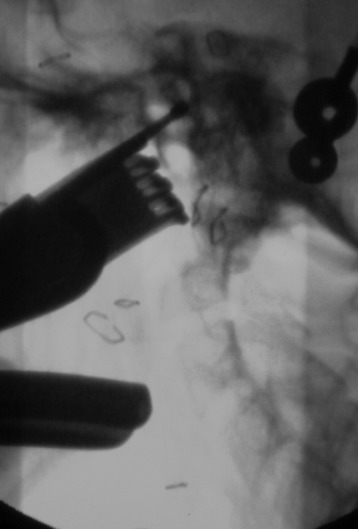

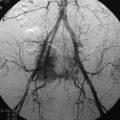

A preoperative MRI showed a multiple septated cystic mass located on the C2 vertebral body protruding anteriorly and pushing the pharyngeal wall (Fig. 18-24). The fluid-fluid level is shown in the cystic mass (Fig. 18-25). The tumor was removed with the transmandibular glossotomy approach, and a fibular strut graft was inserted between the clivus and C3 lower body (Fig. 18-26). Posterior occipitocervical fusion was then carried out with the rod and wiring method (Fig. 18-27). The pathological diagnosis was aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC).

For the treatment of ABC, intralesional excision, radiotherapy, and selective arterial embolization (SAE) have been successfully used, alone or in combination.7 Local recurrences have been reported after curettage with or without bone grafting (10–60%), radiotherapy (14–50%), and embolization (0–14%).8,9 Most recurrences occur within 1 year, and in general, no recurrences are found later than 2 years after treatment.

Several points should be considered for spinal ABC treatment.10 ABC is a benign lesion, spontaneously tending to mature and even to repair. More than 50% of patients are pediatric. Posterior elements are nearly always involved; curettage often removes at least one articular joint, thus requiring surgical stabilization. Recurrence rates after SAE and curettage are comparable in skeletal ABC. SAE, when feasible, can be considered the first treatment option for ABC. In cases of neurological involvement, pathological fracture, technical impossibility of performing embolization, or local recurrence after at least two embolizations, complete lesional excision would be the therapy of choice.

TRANSORAL APPROACH WITH MAXILLOTOMIES11

A 41-year-old woman presented with progressive spastic gait and increased tone in all extremities. A preoperative imaging study revealed that her brainstem was compressed by the high positioned C1 and C2 vertebral bodies (Figs. 18-28 and 18-29).

The operation was performed on the posterior side first. Posterior occipitocervical fusion was carried out using a rod and wiring system (Fig. 18-30).

MAXILLOTOMY, LE FORT TYPE I OSTEOTOMY

MUCOSAL INCISION

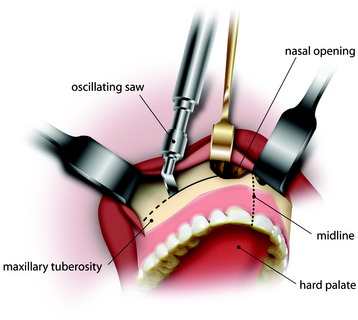

After general anesthesia is induced, a feeding tube is placed. The patient is placed supine with the neck in slight extension. The face, jaw, upper neck, and oropharynx are prepared and exposed. The mucosa is elevated off the upper alveolar margin by local anesthetic injection. A mucosal incision is made under the upper lip along the alveolar margin from one maxillary tuberosity to the other, and the mucoperiosteum on each side is elevated to expose the anterior maxillary surface and nasal opening (Figs. 18-31 and 18-32). The mucosa over the hard palate also is incised in the midline and elevated. This incision is extended through the full thickness of the soft palate to the base of the uvula. Mini-plates are pre-bent and fitted along the maxilla. Drill holes are made and the plates are secured before the osteotomies are made.

Osteotomy

A bilateral Le Fort I osteotomy is performed with an oscillating saw.11 A Gigli saw is used to make a midline parasagittal osteotomy, passing along one side of the vomer and between the two incisors nearest to midline (Figs. 18-33 and 18-34).

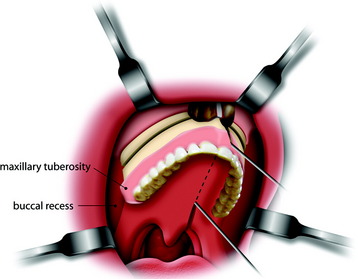

Mobilization Of The Maxilla

The mobile maxilla half is separated from the pterygoid process and swung down and out laterally into the buccal recess. The mobile bone is retracted out of the field, exposing the posterior nasopharynx (Fig. 18-35). The posterior nasal septum is removed as needed. The posterior pharyngeal wall is seen.

Exposure of the Bony Structures

This approach provides wide exposure from the sphenoid sinus to the upper cervical spine. A pharyngeal incision is made on the midline, and the mucoperiosteal layers are spread with a self-retaining retractor. The longus colli and longus capitis muscles and the anterior longitudinal ligament are dissected free. The clivus and C1 anterior arch are then shown. For the removal of the bony structures, a high-speed drill is used (Fig. 18-36). When the bone is removed with the drill, the surgeon should keep in mind that the posterior cortex should be left intact to prevent dural injury. The thin remaining posterior cortical bone can be removed by undercutting with a 1-mm Kerrison punch. Careful attention should be paid to minimize injury to the lower cranial nerves, carotid artery, and jugular vein.