Anesthesia for laryngeal operations

In operations involving the larynx, both the surgeon and the anesthesiologist must share the patient’s airway, making an understanding of the operative and anesthesia requirements and ongoing communication among team members essential. Indications for laryngeal operations include congenital (Box 155-1) and acquired conditions. The main acquired conditions include trauma, inflammatory conditions, and tumor (benign and malignant). Laryngeal signs and symptoms vary from a sore throat and hoarseness to difficulty in breathing, stridor, and, if severe, complete upper airway obstruction. The main types of laryngeal operations that necessitate anesthesia, including management of the airway, are direct laryngoscopy, thyroplasty, laryngectomy, and importantly, trauma to the larynx.

Airway anatomy and physiology

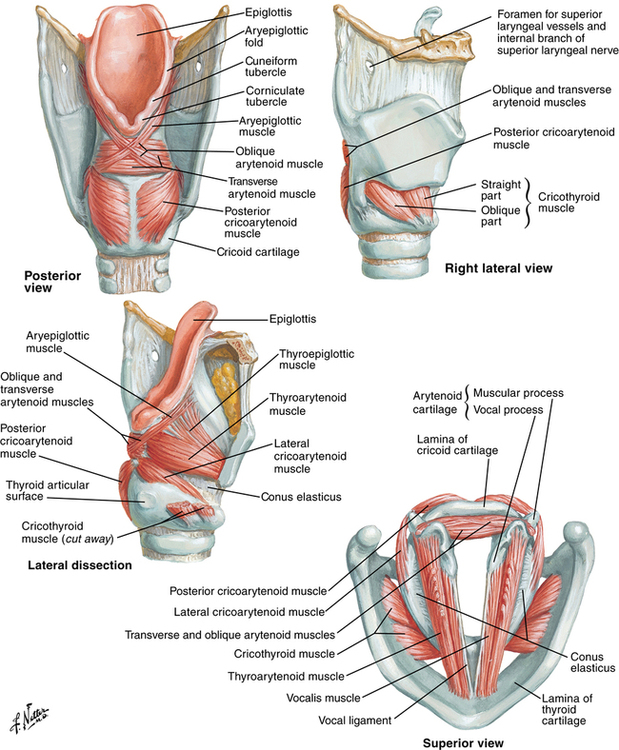

The recurrent laryngeal nerve provides the motor supply to all intrinsic laryngeal muscles except the cricothyroid muscle. The cricothyroid muscle receives motor innervation from the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. The actions of each muscle are summarized in Figure 155-1. There is little chance of effective reinnervation with good laryngeal function when trauma to these nerves occurs.