Anemias Caused by Defects of DNA Metabolism

After completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Discuss the relationships among macrocytic anemia, megaloblastic anemia, and pernicious anemia, and classify anemias appropriately within these categories.

2. Discuss the physiologic roles of folate and vitamin B12 in DNA production and the general metabolic pathways in which they act.

3. Describe the absorption and distribution of vitamin B12, including carrier proteins and the biologic activity of various vitamin-carrier complexes.

4. Describe the biochemical basis for development of anemia with deficiencies of vitamin B12 and folate, and explain the cause of the accompanying megaloblastosis.

5. Recognize individuals at risk for megaloblastic anemia by virtue of age, dietary habits, physiologic circumstance such as pregnancy, drug regimens, or pathologic conditions.

6. Recognize complete blood count, reticulocyte count, red and white blood cell morphologies, and bone marrow findings consistent with megaloblastic anemia.

7. Given the results of tests measuring levels of serum vitamin B12, serum methylmalonic acid, serum folate, plasma or serum homocysteine, and antibodies to intrinsic factor and parietal cells, determine the likely cause of a patient’s deficiency.

8. Recognize results of bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase tests that are consistent with megaloblastic anemia and explain why the test values are elevated in this condition.

Case Study

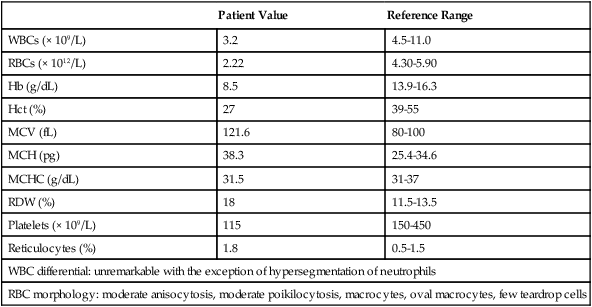

| Patient Value | Reference Range | |

| WBCs (× 109/L) | 3.2 | 4.5-11.0 |

| RBCs (× 1012/L) | 2.22 | 4.30-5.90 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 8.5 | 13.9-16.3 |

| Hct (%) | 27 | 39-55 |

| MCV (fL) | 121.6 | 80-100 |

| MCH (pg) | 38.3 | 25.4-34.6 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 31.5 | 31-37 |

| RDW (%) | 18 | 11.5-13.5 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 115 | 150-450 |

| Reticulocytes (%) | 1.8 | 0.5-1.5 |

| WBC differential: unremarkable with the exception of hypersegmentation of neutrophils | ||

| RBC morphology: moderate anisocytosis, moderate poikilocytosis, macrocytes, oval macrocytes, few teardrop cells | ||

Because of these findings, additional tests were ordered, with the following results:

1. Which of the CBC findings led the physician to order the vitamin assays?

2. Is the patient’s reticulocyte response adequate to compensate for the anemia?

3. Based on the available test results, what can you conclude about the cause of the patient’s anemia?

4. What additional testing would be helpful to diagnose the specific cause of this patient’s anemia?

Etiology

The root cause of megaloblastic anemia is impaired DNA synthesis. The anemia is named for the very large cells of the bone marrow that develop a distinctive morphology (see section on laboratory diagnosis) due to a reduction in the number of cell divisions. Megaloblastic anemia is one example of a macrocytic anemia. Box 20-1 shows the classification of macrocytic anemias. Understanding the etiology of megaloblastic anemia requires a review of DNA synthesis with particular attention to the roles of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) and folic acid (folate).

Physiologic Roles of Vitamin B12 and Folate

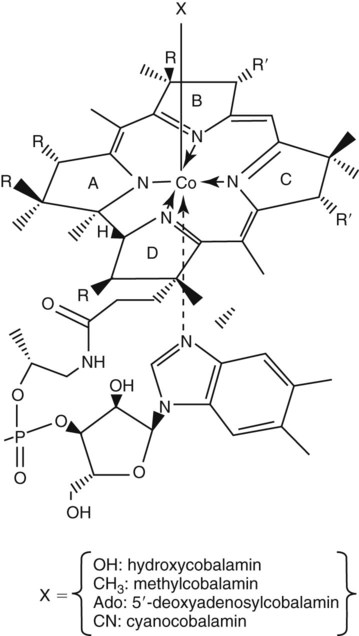

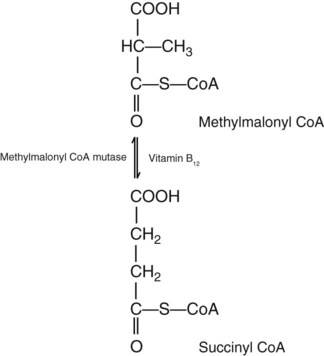

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is an essential nutrient consisting of a tetrapyrrole (corrin) ring containing cobalt that is attached to 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazolyl ribonucleotide (Figure 20-1). Vitamin B12 is a coenzyme in two biochemical reactions in humans. One is isomerization of methylmalonyl coenzyme A (CoA) to succinyl CoA, which requires vitamin B12 (in the adenosylcobalamin form) as a cofactor and is catalyzed by the enzyme methylmalonyl CoA mutase (Figure 20-2). In the absence of vitamin B12, the impaired activity of methylmalonyl CoA mutase leads to a high level of serum methylmalonic acid, which is useful for the diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency (discussed in the section on laboratory diagnosis). The second reaction is the transfer of a methyl group from 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-methyl THF) to homocysteine, which thereby generates methionine. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme methionine synthase and uses vitamin B12 (in the methylcobalamin form) as a coenzyme (discussed later in this section). Methylcobalamin is synthesized through reduction and methylation of vitamin B12. This reaction represents the link between folate and vitamin B12 coenzymes and appears to account for the requirement for both vitamins in normal erythropoiesis.1,2

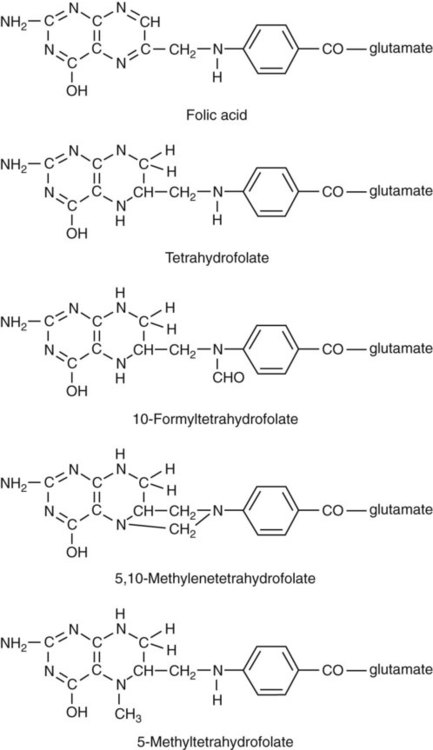

Folate is the general term used for any form of the vitamin folic acid. Folic acid is the synthetic form in supplements and fortified food. Folates consist of a pteridine ring attached to para-aminobenzoate with one or more glutamate residues (Figure 20-3). The function of folate is to transfer carbon units in the form of methyl groups from donors to receptors. In this capacity, folate plays an important role in the metabolism of amino acids and nucleotides. Deficiency of the vitamin leads to impaired cell replication and other metabolic alterations. Folate circulates in the blood predominantly as 5-methyl THF.3 5-Methyl THF is metabolically inactive until it is demethylated to tetrahydrofolate (THF), whereupon folate-dependent reactions may take place.

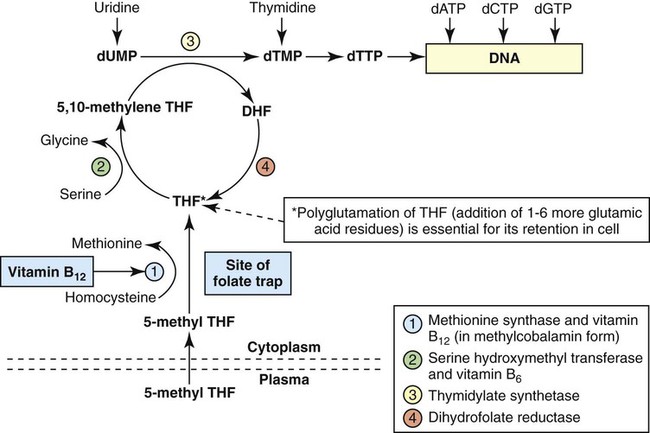

Folate has an important role in DNA synthesis. As seen in Figure 20-4, within the cytoplasm of the cell, a methyl group is transferred from 5-methyl THF to homocysteine, which converts it to methionine and generates THF. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme methionine synthase and requires vitamin B12 in the form of methylcobalamin as a cofactor. THF is then converted to 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-methylene THF); the methyl group for this reaction comes from serine as it is converted to glycine. The methyl group of 5,10-methylene THF is then transferred to deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP), which converts it to deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP). This reaction is catalyzed by thymidylate synthetase and results in the conversion of 5,10-methylene THF to dihydrofolate (DHF). Deoxythymidine monophosphate is a precursor to deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP), which, like the other nucleotide triphosphates, is a building block of the DNA molecule. THF is regenerated by the conversion of DHF to THF by the enzyme DHF reductase. Because some of the folate is catabolized during the cycle, the regeneration of THF also requires additional 5-methyl THF from the plasma. It is important to note that once in the cell, folate is rapidly polyglutamated by the addition of one to six glutamic acid residues. This conjugation is required for retention of THF in the cell and it also promotes attachment of folate to enzymes.4

Defect in Megaloblastic Anemia due to Deficiency in Folate and Vitamin B12

When either folate or vitamin B12 is missing, thymidine nucleotide production for DNA synthesis is impaired. Folate deficiency has the more direct effect, ultimately preventing the methylation of dUMP. The effect of vitamin B12 deficiency is more indirect, preventing the production of THF from 5-methyl THF. When vitamin B12 is deficient, progressively more and more of the folate becomes metabolically trapped as 5-methyl THF. This constitutes what has been called the folate trap as 5-methyl THF accumulates and is unable to supply the folate cycle with THF. Some 5-methyl THF also leaks out of the cell if it is not readily polyglutamated. This results in a decrease in intracellular folate.5 In addition, when either folate or vitamin B12 is deficient, homocysteine accumulates, because vitamin B12 is unable to convert it to methionine (see Figure 20-4).

In this state of diminished thymidine availability, uridine is incorporated into DNA.6,7 The DNA repair process can remove the uridine, but without available thymidine, the repair process is unsuccessful. Although the DNA can unwind and replication can begin, at any point where a thymidine nucleotide is needed, there is essentially an empty space in the replicated DNA sequence, which results in many single-strand breaks. When excisions at opposing DNA strand sites coincide, double-strand breaks occur. Repeated DNA strand breaks lead to fragmentation of the DNA strand.4 The resulting DNA is nonfunctional, and the DNA replication process is incomplete. Cell division is halted, which results in either cell lysis or apoptosis8 of many erythroid cells. Cells that do not lyse are released into the circulation. The dependency of DNA production on folates has been used in cancer chemotherapy (Box 20-2).

In the case of red blood cell (RBC) development, these vitamin deficiencies result in ineffective hematopoiesis with increased apoptosis of erythroid progenitor cells. The remaining erythroid cells are larger than those cells that are normally seen during the final stages of erythropoiesis and their nuclei are immature-appearing compared with the cytoplasm (asynchrony). In contrast to the normally dense chromatin of comparable normoblasts, megaloblastic erythroid precursors have an open, finely stippled, reticular pattern.5 The nuclear changes seen in the megaloblastic cells are related to cell cycle delay, prolonged resting phase, and arrest in nuclear maturation. Electron microscopy has revealed that reduced synthesis of histones is also responsible for morphologic changes in the chromatin of megaloblastic cells, regardless of the causes.9 Because ribonucleic acid (RNA) contains uracil instead of thymidine residues, RNA function is not affected by vitamin B12 or folate deficiency. Thus cytoplasmic development is not generally disturbed in these cells, which results in the asynchrony between cytoplasm and nucleus. Together, the accumulation of cells at earlier stages of differentiation and cells with increased size and immaturity result in the appearance of erythroid cells in the bone marrow that are pathognomonic of megaloblastic anemia.8 Due to the ineffective hematopoiesis, pancytopenia is also evident, with certain distinctive cellular changes (see section on laboratory diagnosis).

Other Causes of Megaloblastosis

Vitamin B12 and folate deficiency are not the only causes of megaloblastic erythrocytes. Dysplastic erythroid cells in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) can also have megaloblastoid features (see Chapter 35). In MDS, the macrocytic erythrocytes and their progenitors characteristically show delayed cytoplasmic and nuclear maturation, including cytoplasmic vacuole formation, nuclear budding, multinucleation, and nuclear fragmentation, and thus may be distinguished from the megaloblastic RBCs seen in the vitamin deficiencies. In addition, nuclear-cytoplasmic asynchrony and megaloblastic RBCs may be seen in congenital dyserythropoietic anemia (CDA) types I and III (see Chapter 21). The CDAs are rare conditions that usually manifest in childhood and may be distinguished from the acquired causes of megaloblastosis by clinical history and morphologic differences. In CDA I internuclear chromatin bridging of erythroid cells or binucleated forms are observed, and in CDA III giant multinucleated erythroblasts are present. Another rare condition in which RBC precursors have a megaloblastic appearance is acute erythroleukemia, previously classified as FAB M6 (see Chapter 36). In this condition, the cells are macrocytic, and the immature appearance of the nuclear chromatin is similar to the more open appearance of the chromatin in megaloblasts. There are usually other aberrant findings in erythroleukemia, including an increase of myeloblasts in the bone marrow; however, an experienced morphologist can discern the subtle differences. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors, used to treat human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, interfere with DNA production and may also lead to megaloblastic changes.10

Systemic Manifestations of Folate and Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Although the blood pictures seen with the two vitamin deficiencies are indistinguishable, the clinical presentations vary. In vitamin B12 deficiency, neurologic symptoms may be pronounced and may even occur in the absence of anemia.5 These include memory loss, numbness and tingling in toes and fingers, loss of balance, and further impairment of walking by loss of vibratory sense, especially in the lower limbs.11 Neuropsychiatric symptoms may also be present, including personality changes and psychosis. These symptoms seem to be the result of demyelinization of the spinal cord and peripheral nerves, but the relationship of this demyelinization to vitamin B12 deficiency is unclear. The role of increases in tumor necrosis factor-α, a neurotoxic agent, and decreases in epidermal growth factor, a neurotrophic agent, in the development of neurologic symptoms in vitamin B12-deficient patients is being researched.12,13

At one time, folate deficiency was believed to be more benign clinically than vitamin B12 deficiency. Later research suggested that low levels of folate and the resulting high homocysteine levels were risk factors for cardiovascular disease.14 More recent research has not substantiated this association,15–17 although some point out that high folate levels provide a cardioprotective effect in diabetic patients and certain ethnic populations.18,19 The evidence at this time is unclear as to whether persistent suboptimal folate status may have a significant long-term health impact. In addition, there is evidence of depression, peripheral neuropathy, and psychosis related to folate deficiency.20–22 Folate levels appear to influence the effectiveness of treatments for depression.23 Folate deficiency during pregnancy can result in impaired formation of the fetal nervous system, resulting in neural tube defects such as spina bifida,24 despite the fact that the fetus accumulates folate at the expense of the mother. Pregnancy requires a considerable increase in folate to fulfill the requirements related to rapid fetal growth, uterine expansion, placental maturation, and expanded blood volume.3 Ensuring adequate folate levels in women of childbearing age is particularly important because many women are likely to be unaware of their pregnancy during the first crucial weeks of fetal development. Fortification of the U.S. food supply with folic acid in grain and cereal products was mandated by the Food and Drug Administration in 1998 to lower the risk of neural tube defects in the unborn.

Causes of Vitamin Deficiencies

Folate Deficiency

Inadequate Intake

The most common cause of folate deficiency is inadequate dietary intake.25 Folate is ubiquitous in foods, but a generally poor diet can result in deficiency. Good sources of folate include leafy green vegetables, dried beans, liver, beef, fortified breakfast cereals, and some fruits, especially oranges.26 Folates are heat labile, and overcooking of foods can diminish their nutritional value.3

Impaired Absorption

Folates are absorbed from the diet in the small intestine; however, only 50% of what is ingested is available for absorption.3 A rare autosomal recessive deficiency of a folate transporter protein (PCFT/HCP1) severely decreases intestinal absorption of folate.27 Once across the intestinal cell, most folate is transported in the plasma as 5-methyl THF unbound to any specific carrier.11 Its entry into cells, however, is carrier mediated.28

Folate absorption may also be impaired by intestinal disease, especially sprue. Sprue is characterized by weakness, weight loss, and steatorrhea (fat in the feces), which is evidence that the intestine is not absorbing food properly. It is seen in the tropics (tropical sprue), where its cause is generally considered to be overgrowth of enteric pathogens.29 Celiac disease (nontropical sprue) has been traced to intolerance of the gluten in some grains29 (gluten-induced enteropathy) and can be controlled by eliminating wheat, barley, and rye products from the diet. Surgical resection of the small intestine and inflammatory bowel disease can also decrease folate absorption.

Impaired Use of Folate

Numerous drugs impair folate metabolism (Box 20-3).30,31 Antiepileptic drugs are particularly known for this,32 and the result is macrocytosis with frank megaloblastic anemia. In most instances, folic acid supplementation is sufficient to override the impairment and allow the patient to continue therapy.33

Excessive Loss of Folate

Physiologic loss of folate occurs through the kidney. The amount is small and not a cause of deficiency. Patients undergoing renal dialysis lose folate in the dialysate, however; thus supplemental folic acid is routinely provided to these individuals to prevent megaloblastic anemia.11

Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Inadequate Intake

True dietary deficiency of vitamin B12 is possible for strict vegetarians (vegans) who do not eat meat, eggs, or dairy products. Although it is an essential vitamin for animals, plants cannot synthesize vitamin B12, and it is not available from vegetable sources. The best dietary sources are animal products such as liver, milk, cheese, and eggs.25

Impaired Absorption

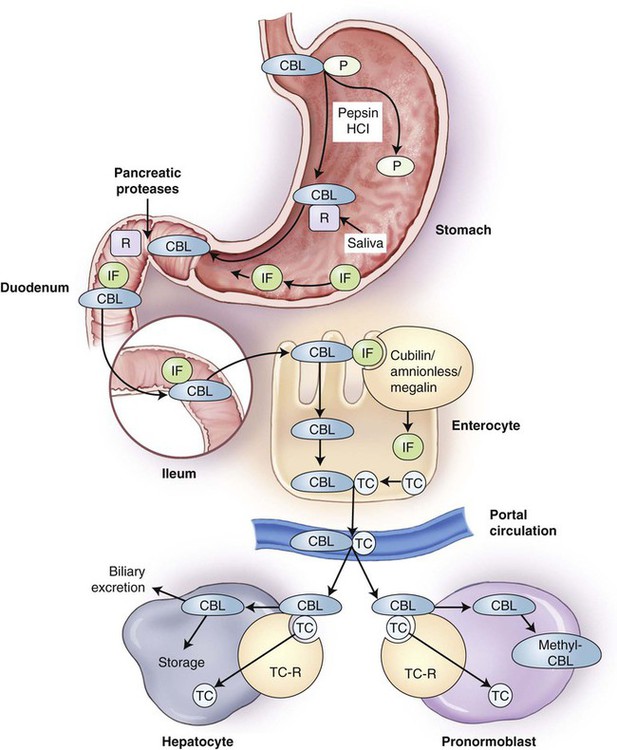

Vitamin B12 in food is released from food proteins primarily in the acid environment of the stomach, aided by pepsin, and is subsequently bound by a specific salivary protein, haptocorrin, also known as R-binder protein (Figure 20-5). In the small intestine, vitamin B12 is released from haptocorrin by the action of pancreatic proteases, including trypsin. It is then bound by intrinsic factor, produced by the gastric parietal cells. Vitamin B12 binding to intrinsic factor is required for absorption by the ileal cells (enterocytes) that possess receptors for the complex. These receptors are cubilin-amnionless complex, which binds the vitamin B12–intrinsic factor compound, and megalin, a membrane transport protein.34–37 Once in the enterocyte, the vitamin B12 is then freed from intrinsic factor and bound to transcobalamin (previously called transcobalamin II) and released into the circulation. In the plasma, only 20% of the vitamin B12 is bound to transcobalamin; the remaining 80% is bound to transcobalamin I and III, referred to as the haptocorrins.34,38 The vitamin B12–transcobalamin complex, termed holotranscobalamin, is the metabolically active form of vitamin B12. Holotranscobalamin binds to specific receptors on the surfaces of many different types of cells and enters the cells by endocytosis, with subsequent release of vitamin B12 from the carrier.39 The body maintains a substantial reserve of absorbed vitamin B12 in hepatocytes.

Failure to Separate Vitamin B12 from Food Proteins

A condition known as food-cobalamin malabsorption is characterized by hypochlorhydria and the resulting inability of the body to release vitamin B12 from food or intestinal transport proteins for subsequent binding to intrinsic factor. Food-cobalamin malabsorption is caused primarily by atrophic gastritis or atrophy of the stomach lining that often occurs with increasing age.40 Because histamine 2 receptor blockers and proton pump inhibitors lower gastric acidity, the long-term use of these drugs for the treatment of ulcers and gastroesophageal reflux disease, as well as gastric bypass surgery, also induce food-cobalamin malabsorption.40

Lack of Intrinsic Factor

Pernicious anemia

Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune disorder characterized by impaired absorption of vitamin B12 due to a lack of intrinsic factor.41 This condition is called pernicious anemia because the disease was fatal before its cause was discovered. The incidence is approximately 25 per 100,000 persons older than 40 years of age.5 Pernicious anemia most often manifests in the sixth decade or later, but can also be found in children.

In pernicious anemia, autoimmune lymphocyte-mediated destruction of gastric parietal cells severely reduces the amount of intrinsic factor secreted in the stomach. Pathologic CD4 T cells inappropriately recognize and initiate an autoimmune response against the H+/K+–adenosine triphosphatase embedded in the membrane of the parietal cells.42 A chronic inflammatory infiltration follows, which extends into the wall of the stomach.41 Over a period of years and even decades, there is progressive development of atrophic gastritis resulting in the loss of the parietal cells with their secretory products, H+ and intrinsic factor. The loss of H+ production in the stomach constitutes achlorhydria. Low gastric acidity was previously an important diagnostic criterion for pernicious anemia. The absence of intrinsic factor can also be detected using the Schilling test. However, because the test requires a 24-hour urine collection and the use of radioactive cobalt in vitamin B12 to trace absorption, it has fallen from favor, and safer diagnostic tests are preferred (see section on laboratory diagnosis).

Another feature of the autoimmune response in pernicious anemia is the production of antibodies to intrinsic factor43 and gastric parietal cells44 that are detectable in serum. The most common antibody to intrinsic factor blocks the site on intrinsic factor where vitamin B12 binds,41 which inhibits the formation of the intrinsic factor–vitamin B12 complex and prevents the absorption of the vitamin. These blocking antibodies are present in about 70% of patients with pernicious anemia.41 Parietal cell antibodies are detectable in about 90% of patients with pernicious anemia.41

Other causes of lack of intrinsic factor

A lack of intrinsic factor may also be related to H. pylori infection. Left untreated, colonization of the gastric mucosa with H. pylori progresses until the parietal cells are entirely destroyed, a process involving both local and systemic immune processes.45,46 In addition, partial or total gastrectomy, which result in removal of intrinsic factor–producing parietal cells, invariably leads to vitamin B12 deficiency.

Impaired absorption of vitamin B12 can also be caused by hereditary intrinsic factor deficiency. This is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by the absence or nonfunctionality of intrinsic factor. In contrast to the acquired forms of pernicious anemia, histology and gastric acidity are normal.36

Inherited Errors of Vitamin B12 Absorption and Transport

Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive condition caused by mutations in the genes for either cubilin or amnionless. This defect results in decreased endocytosis of the intrinsic factor–vitamin B12 complex by ileal cells. Transcobalamin deficiency is another rare autosomal recessive condition resulting in a deficiency of physiologically available vitamin B12.36,47

Competition for Vitamin B12

Competition for available vitamin B12 in the intestine may come from intestinal organisms. The fish tapeworm Diphyllobothrium latum is able to split vitamin B12 from intrinsic factor,48 rendering the vitamin unavailable for host absorption. Also, blind loops, portions of the intestines that are stenotic as a result of surgery or inflammation, can become overgrown with intestinal bacteria that compete effectively with the host for available vitamin B12.11 In both of these cases, the host is unable to absorb sufficient vitamin B12, and megaloblastic anemia results.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Screening Tests

Complete Blood Count

Slight macrocytosis often is the earliest sign of megaloblastic anemia. Patients with uncomplicated megaloblastic anemia are expected to have decreased hemoglobin and hematocrit values, pancytopenia, and reticulocytopenia. Megaloblastic anemia develops slowly, and the degree of anemia is often severe when first detected. Hemoglobin values of less than 7 or 8 g/dL are not unusual.4 When the hematocrit is less than 20%, erythroblasts with megaloblastic nuclei, including an occasional promegaloblast, may appear in the peripheral blood. The mean cell volume (MCV) is usually 100 to 150 fL and commonly is greater than 120 fL, although coexisting iron deficiency, thalassemia trait, or inflammation can prevent macrocytosis. The mean cell hemoglobin (MCH) is elevated by the increased volume of the cells, but the mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) is usually within the reference range, because hemoglobin production is unaffected. The RBC distribution width (RDW) is also elevated.

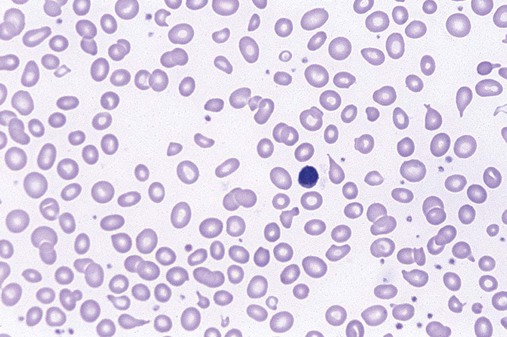

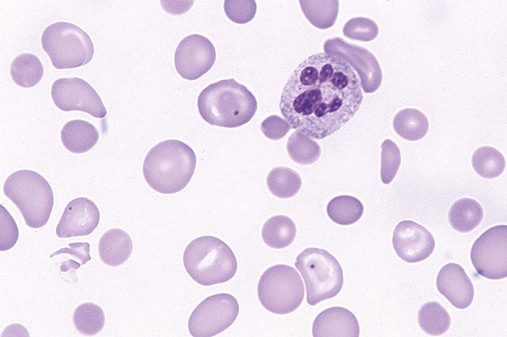

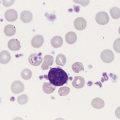

The characteristic morphologic findings of megaloblastic anemia in the peripheral blood include oval macrocytes (enlarged oval RBCs) (Figure 20-6) and hypersegmented neutrophils with six or more lobes (Figure 20-7).49 Impaired cell production results in a low absolute reticulocyte count, especially in light of the severity of the anemia, and polychromasia is not seen on the peripheral blood film. Additional morphologic changes may include the presence of teardrop cells, RBC fragments, and microspherocytes. These smaller cells further increase the RDW. Nucleated RBCs, Howell-Jolly bodies, basophilic stippling, and Cabot rings may be observed.

White Blood Cell Manual Differential

Hypersegmentation of the neutrophils is essentially pathognomonic for megaloblastic anemia. It appears early in the course of the disease50 and may persist for up to 2 weeks after treatment is initiated.5 Hypersegmented neutrophils noted in the WBC differential report is a significant finding and requires a reporting rule that can be applied consistently, because even healthy individuals may have an occasional one. One such rule is to report hypersegmentation when there are at least 5 five-lobed neutrophils per 100 WBCs or at least 1 six-lobed neutrophil is noted.11 Some laboratories perform a lobe count on 100 neutrophils and then calculate the mean. In megaloblastic anemia, the mean lobe count should be greater than 3.4.11 The cause of the hypersegmentation is not understood, despite considerable investigation.51 More recent advances in the understanding of growth factors and their impact on transcription factors may yet solve this mystery. Nevertheless, a search for neutrophil hypersegmentation on a peripheral blood film constitutes an inexpensive yet sensitive screening test for megaloblastic anemia.

Bilirubin and Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels

The constellation of findings including macrocytic anemia, moderate to marked pancytopenia, reticulocytopenia, oval macrocytes, hypersegmented neutrophils, plus increased levels of total and indirect bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase justifies further testing to confirm a diagnosis of megaloblastic anemia and determine its cause. Occasionally, the classic findings may be obscured by coexisting conditions such as iron deficiency, which makes the diagnosis more challenging. Most hematologic aberrations do not appear until vitamin deficiency is fairly well advanced (Box 20-4).52

Specific Diagnostic Tests

Bone Marrow Examination

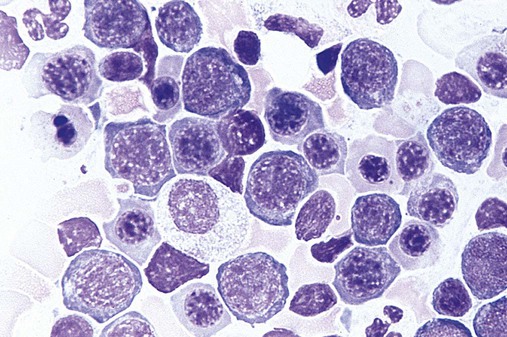

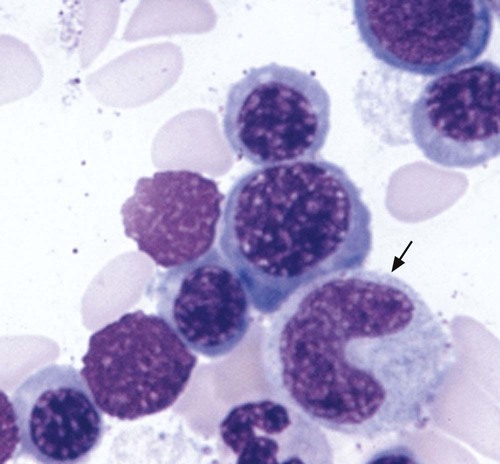

Megaloblastic, in contrast to macrocytic, anemia refers to specific morphologic changes in the developing RBCs. The cells are characterized by a nuclear-cytoplasmic asynchrony in which the cytoplasm matures as expected with increasing pinkness as hemoglobin accumulates. The nucleus lags behind, however, appearing younger than expected for the degree of maturity of the cytoplasm (Figure 20-8). This asynchrony is most striking at the stage of the polychromatophilic normoblast. The cytoplasm appears pinkish blue as expected for that stage, but the nuclear chromatin remains more open than expected, similar to that in the nucleus of a basophilic normoblast. Overall, the marrow is hypercellular, with a myeloid-to-erythroid ratio of about 1 : 1 by virtue of the increased erythropoietic activity. The hematopoiesis is ineffective, however, and although cell production in the bone marrow is increased, the death of cells in the marrow results in peripheral pancytopenia.

The WBCs are also affected in megaloblastic anemia and appear larger than normal. This is most evident in metamyelocytes and bands, because in the usual development of neutrophils, the cells should be getting smaller at these stages. The effect creates what are called “giant” metamyelocytes (Figure 20-9) and bands.

Assays for Folate, Vitamin B12, Methylmalonic Acid, and Homocysteine

Although bone marrow aspiration is confirmatory for megaloblastosis, the invasiveness of the procedure and its expense mean that other testing is performed more often than a bone marrow examination. Furthermore, the confirmation of megaloblastic morphology in the marrow does not identify its cause. Tests for serum levels of folate and vitamin B12 are readily available using immunoassay. RBC folate levels may also be measured. Unlike serum folate levels, which fluctuate with diet, RBC folate values are stable and may be a more accurate reflection of true folate status53; however, current RBC folate tests have less than optimal sensitivity and specificity and have not been validated in actual patients with normal and deficient folate levels. Thus the serum folate level is preferred over RBC folate level in the United States as the initial test for evaluation of folate deficiency.5

Some laboratories conduct a reflexive assay for methylmalonic acid if vitamin B12 levels are low. As indicated previously, in addition to playing a role in folate metabolism, vitamin B12 is a cofactor in the conversion of methylmalonyl CoA to succinyl CoA by the enzyme methylmalonyl CoA mutase (see Figure 20-2). If vitamin B12 is deficient, methylmalonyl CoA accumulates. Some of it hydrolyzes to methylmalonic acid, and the increase can be detected in serum and urine. Because methylmalonic acid is also elevated in patients with impaired renal function, increased levels cannot be definitively related to vitamin B12 deficiency.25 Methylmalonic acid is assayed by gas chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry.

Homocysteine levels are affected by folate and vitamin B12. 5-Methyl THF donates a methyl group to homocysteine in the generation of methionine. This process uses vitamin B12 as a coenzyme (see Figure 20-4). Thus, a deficiency in either folate or vitamin B12 results in elevated levels of homocysteine. Total homocysteine can be measured in either plasma or serum. Homocysteine may be assayed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, high-performance liquid chromatography, or fluorescence polarization immunoassay. Homocysteine levels are also elevated in patients with renal failure and dehydration.

Holotranscobalamin Assay

Holotranscobalamin is the metabolically active form of vitamin B12. Until recently, methods for measuring holotranscobalamin were manual and not suitable for use in clinical laboratories. Newer, more rapid immunoassays using monoclonal antibodies specific for holotranscobalamin have been developed in the past several years that are both sensitive and specific.54,55

Deoxyuridine Suppression Test

The principle of the deoxyuridine suppression test is that the preincubation of normal bone marrow with deoxyuridine will suppress the subsequent incorporation of labeled thymidine into DNA, because the normal cells can successfully methylate the uridine into thymidine. However, in patients with either a vitamin B12 or a folate deficiency, this suppression is abnormally low. By adding either vitamin B12 or folate to the test cells, one can determine whether the inadequate suppression is caused by vitamin B12 or folate deficiency.56–58 Although micromethods have been developed, the necessity of using bone marrow tissue and the complexity of the test make it impractical for clinical testing.

Stool Analysis for Parasites

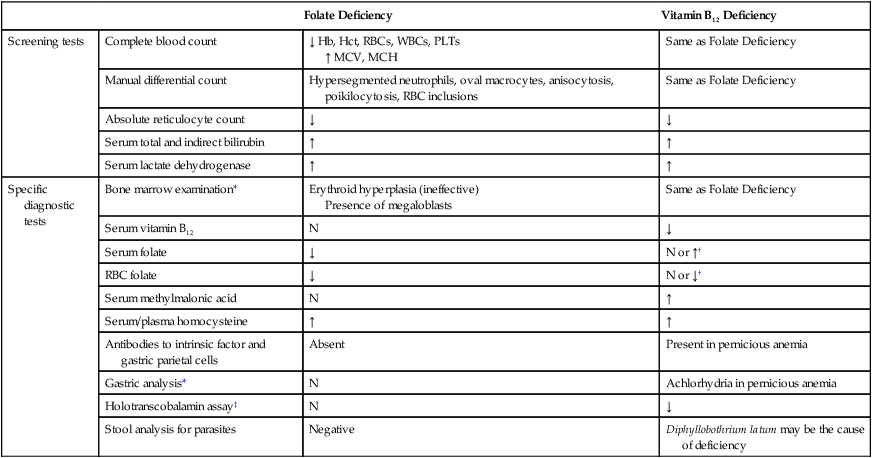

See Table 20-1 for a summary of laboratory tests used to diagnose vitamin B12 and folate deficiency.

TABLE 20-1

Laboratory Tests Used to Diagnose Vitamin B12 and Folate Deficiency

| Folate Deficiency | Vitamin B12 Deficiency | ||

| Screening tests | Complete blood count | ↓ Hb, Hct, RBCs, WBCs, PLTs ↑ MCV, MCH |

Same as Folate Deficiency |

| Manual differential count | Hypersegmented neutrophils, oval macrocytes, anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, RBC inclusions | Same as Folate Deficiency | |

| Absolute reticulocyte count | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Serum total and indirect bilirubin | ↑ | ↑ | |

| Serum lactate dehydrogenase | ↑ | ↑ | |

| Specific diagnostic tests | Bone marrow examination* | Erythroid hyperplasia (ineffective) Presence of megaloblasts |

Same as Folate Deficiency |

| Serum vitamin B12 | N | ↓ | |

| Serum folate | ↓ | N or ↑† | |

| RBC folate | ↓ | N or ↓† | |

| Serum methylmalonic acid | N | ↑ | |

| Serum/plasma homocysteine | ↑ | ↑ | |

| Antibodies to intrinsic factor and gastric parietal cells | Absent | Present in pernicious anemia | |

| Gastric analysis* | N | Achlorhydria in pernicious anemia | |

| Holotranscobalamin assay‡ | N | ↓ | |

| Stool analysis for parasites | Negative | Diphyllobothrium latum may be the cause of deficiency |

*Bone marrow examination and gastric analysis are not usually required for diagnosis.

†Without vitamin B12, the cell is unable to produce intracellular polyglutamated tetrahydrofolate; therefore, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate leaks out of the cell, which results in a decreased level of intracellular folate.

‡Holotranscobalamin level is also decreased in transcobalamin deficiency.

Macrocytic Nonmegaloblastic Anemias

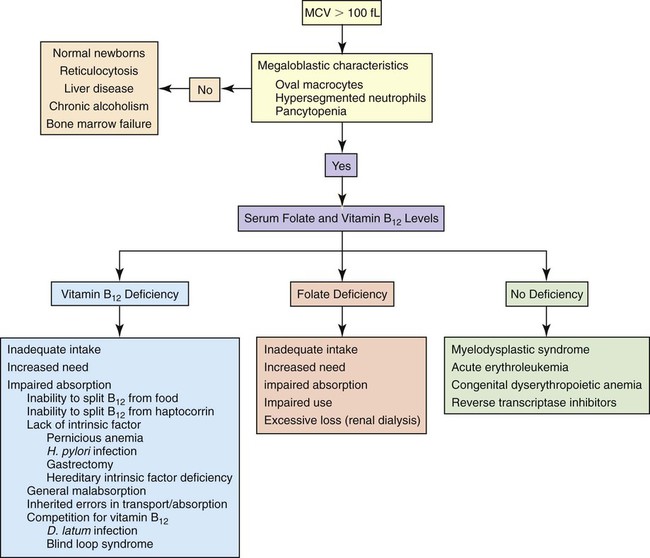

The macrocytic nonmegaloblastic anemias are macrocytic anemias in which DNA synthesis is unimpaired. The macrocytosis tends to be mild; the MCV usually ranges from 100 to 110 fL and rarely exceeds 120 fL. Patients with nonmegaloblastic, macrocytic anemia lack hypersegmented neutrophils and oval macrocytes in the peripheral blood and megaloblasts in the bone marrow. Macrocytosis may be physiologically normal, as in the newborn (see Chapter 38), or the result of pathology, as in liver disease, chronic alcoholism, or bone marrow failure. Reticulocytosis is a common cause of macrocytosis. Figure 20-10 presents an algorithm for the preliminary investigation of macrocytic anemias.

Treatment

Treatment should be directed at the specific vitamin deficiency established by the diagnostic tests and should include addressing the cause of the deficiency (e.g., better nutrition, treatment for D. latum), if possible. Vitamin B12 is administered intramuscularly to treat pernicious anemia to bypass the need for intrinsic factor. Large doses of oral vitamin B12 have been proposed to be effective in the treatment of pernicious anemia40,59; however, this treatment has not been validated in clinical practice. Folic acid can be administered orally. The inappropriate treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency with folic acid improves the anemia, but does not correct or stop the progress of the neurologic damage, which may advance to an irreversible state.25 Thus proper diagnosis prior to treatment is important. Iron is often supplemented concurrently to support the rapid cell production that accompanies effective treatment.

When proper treatment is initiated, the body’s response is prompt and brisk and can be used to confirm the accuracy of the diagnosis. The bone marrow morphology will begin to revert to a normoblastic appearance within a few hours of treatment. A substantial reticulocyte response is apparent at about 1 week, with hemoglobin increasing toward normal levels in about 3 weeks.11 Hypersegmented neutrophils disappear from the peripheral blood within 2 weeks.5 Thus, with proper treatment, hematologic parameters may return to normal within 3 to 6 weeks.

Summary

• Impaired DNA synthesis affects all rapidly dividing cells of the body, including the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and bone marrow. The effect on hematologic cells results in megaloblastic anemia, so named for the very large RBCs that develop in the bone marrow.

• Vitamin B12 and folate are needed for the production of thymidine nucleotides for DNA synthesis. Deficiencies of either vitamin impair DNA replication, halt cell division, and increase apoptosis, which results in ineffective erythropoiesis and megaloblastic morphology.

• Patients with vitamin B12 or folate deficiency develop megaloblastic anemia and the general symptoms of anemia. Patients with vitamin B12 deficiency may develop neuropathies and neuropsychiatric abnormalities as a result of demyelinization of nerves in the peripheral and central nervous system. Folate deficiency, in particular, leads to elevation of homocysteine levels and possible risk of coronary artery disease. Peripheral neuropathy and depression also may accompany folate deficiency. Folate deficiency in early pregnancy can lead to neural tube defects in the fetus.

• Folate deficiency may result from inadequate intake, increased need with growth or pregnancy, impaired absorption, impaired use, or excessive loss. The action of folates can be impaired by drugs such as those used to treat epilepsy or cancer. Renal dialysis patients experience significant folate loss to the dialysate.

• Vitamin B12 deficiency arises from inadequate intake, increased need, or inadequate absorption. Inadequate intake of vitamin B12, although possible, is uncommon, because vitamin B12 is ubiquitous in animal products. Pregnancy, lactation, and growth create increased need for vitamin B12.

• Absorption of vitamin B12 depends on production of intrinsic factor by parietal cells of the stomach.

• Impaired absorption of vitamin B12 can be caused by several mechanisms. Decrease in gastric acid production or lack of trypsin in the intestine causes vitamin B12 to be excreted in the stool rather than absorbed. Malabsorption can be caused by intestinal diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease. Competition for vitamin B12 can develop from an intestinal parasite (D. latum) or bacteria in intestinal blind loops. Lack of intrinsic factor may result from loss of gastric parietal cells with pernicious anemia, H. pylori infection, gastrectomy, or inherited intrinsic factor deficiency.

• Pernicious anemia is vitamin B12 deficiency resulting from an autoimmune disease that causes atrophic destruction of gastric parietal cells. H+ and intrinsic factor secretion is lost. Antibodies to parietal cells or intrinsic factor or both are detectable in the serum.

• Classic CBC findings in megaloblastic anemia include decreased hemoglobin level, hematocrit, and RBC count; leukopenia; thrombocytopenia; decreased absolute reticulocyte count; elevated MCV (usually greater than 120 fL); elevated RDW and MCH; MCHC within the reference range; oval macrocytes; and hypersegmented neutrophils. Additional abnormal laboratory test findings may include elevated levels of total and indirect serum bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase due to the ineffective erythropoiesis and intramedullary hemolysis.

• The bone marrow in megaloblastic anemia is hyperplastic with increased erythropoiesis; however, it is ineffective due to increased apoptosis of developing cells. RBC precursors show nuclear-cytoplasmic asynchrony, with the nuclear maturation lagging behind the cytoplasmic maturation. Giant metamyelocytes and bands are evident.

• The cause of megaloblastic anemia is determined using specific immunoassays for serum and RBC folate and serum vitamin B12. Immunoassays for antibodies to intrinsic factor and parietal cells can aid in the diagnosis of pernicious anemia. Additional tests for gastrointestinal disease or parasites may be needed.

• Treatment of megaloblastic anemia is directed at correcting the cause of the deficiency, supplementing the missing vitamin, or both.

• For pernicious anemia, lifelong supplementation with vitamin B12 is necessary.

Review Questions

1. Which of the following findings is consistent with a diagnosis of megaloblastic anemia?

a. Hyposegmentation of neutrophils

b. Decreased serum lactate dehydrogenase level

2. A patient has a clinical picture of megaloblastic anemia. The serum folate level is decreased, and the serum vitamin B12 level is normal. What is the expected value for the methylmalonic acid assay?

3. Which one of the following statements characterizes the relationships among macrocytic anemia, megaloblastic anemia, and pernicious anemia?

a. Macrocytic anemias are megaloblastic.

b. Macrocytic anemia is pernicious anemia.

4. Which of the following CBC findings is most suggestive of a megaloblastic anemia?

5. In the following description of a bone marrow smear, find the statement that is inconsistent with the expected picture in megaloblastic anemia.

6. Which of the following findings would be inconsistent with elevated titers of parietal cell antibodies?

7. Which of the following is the most metabolically active form of absorbed vitamin B12?

8. Folate and vitamin B12 work together in the production of:

9. The macrocytosis associated with megaloblastic anemia results from:

a. Reduced numbers of cell divisions

b. Activation of a gene that is typically active only in megakaryocytes

c. Reduced concentration of hemoglobin in the cells so that larger cells are needed to provide the same oxygen-carrying capacity

d. Increased production of reticulocytes in an attempt to compensate for the anemia

10. Individuals of which one of the following groups are at highest risk for pernicious anemia?