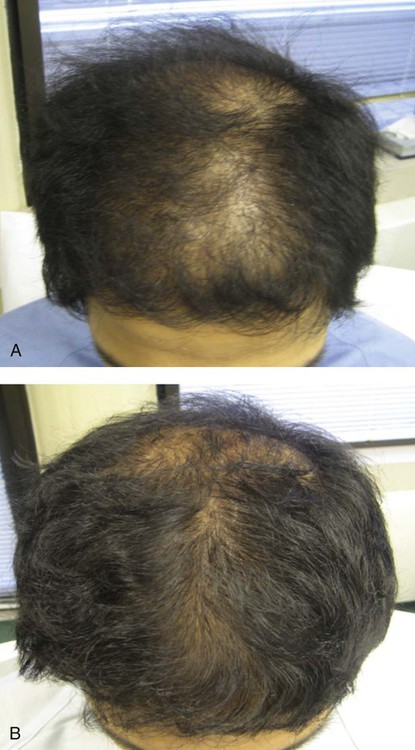

Androgenetic alopecia

Medical therapies

Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of dutasteride 0.5 mg once daily in male patients with male pattern hair loss: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study.

Eun HC, Kwon OS, Yeon JH, Shin HS, Kim BY, Ro BI, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010; 63: 252–8.

Dutasteride is not currently licensed for treatment of hair loss.

Topical minoxidil (2% and 5%) once or twice daily

Topical minoxidil (2% and 5%) once or twice daily Finasteride 1 mg once a day

Finasteride 1 mg once a day Spironolactone 100–200 mg/day

Spironolactone 100–200 mg/day Cyproterone acetate 50–100 mg/day for days 5 to 15 of menstrual cycle, combined with oral estinyl 20 µg twice daily for days 5 to 24 of cycle

Cyproterone acetate 50–100 mg/day for days 5 to 15 of menstrual cycle, combined with oral estinyl 20 µg twice daily for days 5 to 24 of cycle Follicular unit transplantation

Follicular unit transplantation Alopecia reduction

Alopecia reduction Follicular unit extraction

Follicular unit extraction Camouflage

Camouflage