Chapter 20 Urinary and male genital tracts

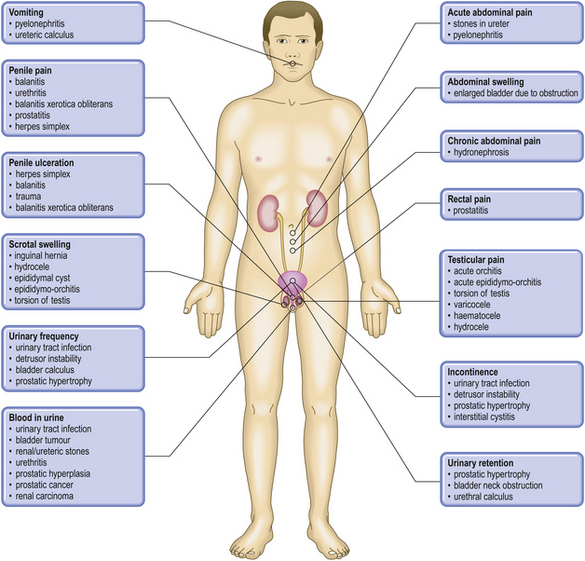

COMMON CLINICAL PROBLEMS FROM DISEASES OF THE URINARY AND MALE GENITAL TRACTS

Pathological basis of clinical signs and symptoms in the urinary and male genital tracts

| Sign or symptom | Pathological basis |

|---|---|

| Abnormal micturition | |

Inflammation of the urethra, often accompanying a urinary tract infection

Obstructed urinary outflow, usually due to prostate gland enlargement

Incomplete bladder emptying due to obstructed urinary outflow

Severe obstruction to bladder outflow, usually due to prostate gland enlargementUrethral dischargeUrethritis, possibly due to sexually transmitted infections (e.g. gonorrhoea)Scrotal swelling

Inflammation or ischaemia of the testis

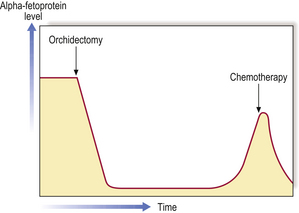

Enlargement of scrotal contents due to hernia, fluid (e.g. hydrocele), varicocele or tumourGenital ulcerationOften sexually transmitted infection (e.g. syphilis)Bone painIf associated with male genital tract disease, possibly due to metastases from prostatic adenocarcinomaRaised serum prostate specific antigenSecreted by prostatic carcinomaRaised serum alpha-fetoprotein and/or human chorionic gonadotrophinTesticular germ cell neoplasia, particularly teratoma/non-seminomatous germ cell tumourGynaecomastiaPossible manifestation of Leydig cell or germ cell tumour of testisInfertilityImpaired spermatogenesis due to endocrine disorders or to testicular lesions, or impaired ejaculation due to obstruction or to neurological disorders

URINARY CALCULI

Urinary calculi (stones) occur in 1–5% of the population in the UK, mainly those aged over 30 years, and with a male preponderance. They may form anywhere in the urinary tract, but the commonest site is within the renal pelvis. They present as:

Calculi form in the urine either because substances are in such an excess that they precipitate, or because other factors affecting solubility are upset. Factors influencing stone formation include the pH of the urine, which can be influenced by both bacterial activity and metabolic factors. Substances in the urine normally inhibit precipitation of crystals, notably pyrophosphates and citrates. The mucoproteins in the urine are thought to provide the organic nidus on which the crystals focus.

Calculi are classified according to their composition. The categories are:

Fig. 20.1 ‘Staghorn’ calculus. The shape of the stone is moulded to that of the pelvis and calyceal system in which it has formed.

Only 10% of patients with calcium-containing stones have hyperparathyroidism or some other cause of hypercalcaemia. However, most have increased levels of calcium in the urine, attributable to a defect in the tubular reabsorption. In the remaining patients, with idiopathic hypercalciuria, no known cause has been identified. The association of uric acid with calcium stones is probably because urates can initiate precipitation of oxalate from solution.

Magnesium ammonium phosphate stones are particularly associated with urinary tract infections with bacteria, such as Proteus, that are able to break down urea to form ammonia. The alkaline conditions thus produced, together with sluggish flow, cause precipitation of these salts, and large staghorn calculi form a cast of the pelvicalyceal system. Staghorn calculi remain in the pelvis for many years and may cause irritation, with subsequent squamous metaplasia or, in some cases, squamous carcinoma.

Uric acid stones occur in patients with gout (Ch. 7). Uric acid precipitates in acid urine. The stones are radiolucent.

RENAL TUMOURS

RENAL CELL CARCINOMA

Incidence

Renal cell carcinoma arises from epithelial cells in the kidney. About 7400 new cases a year are diagnosed in the UK, 3% of all cancers, with around 4000 deaths a year. The incidence in the UK is gradually increasing but this may be due to higher detection rates by improved imaging techniques. There is a male:female ratio of 3:2. Renal cell carcinoma is rare before the age of 40 years and the peak incidence occurs between the ages of 65 and 80 years.

Predisposing factors

Tobacco smoking, obesity, radiation and acquired renal cystic disease are the main environmental risks for renal cell carcinoma. On average, current smokers have a 50% increased risk and about 25% of all renal cell carcinoma cases can be attributed to smoking. Renal cell cancer risk increases by 7% for each unit increase in body mass index, and overall the obesity risk accounts for about 25% of cases. The radiation risk is usually acquired through treatment of other cancers such as cervical and testicular cancer. Acquired cystic kidney disease, commonly seen in patients with renal failure on dialysis, results in a three- to four-fold increased risk of renal cell cancer.

Most cases of renal cell cancer are sporadic but there are some rare inherited disorders that predispose to development of this tumour. The most illustrative is von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease where there are mutations in the VHL gene, which normally produces a protein responsible for degrading proteins of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) family. In the absence of this functioning protein there is accumulation of the HIF family of proteins, which in turn results in increased transcription of hypoxia-associated genes which promote cell growth, survival and angiogenesis. In VHL disease the risk of developing renal cell cancer is 70% by the age of 60 years with multiple and bilateral tumours; these patients are also at risk of epididymal, cerebral and other tumours (Ch. 26). The largest subgroup of sporadic renal cell carcinoma (clear cell carcinoma) has loss of expression of the VHL gene.

Presentation

Some 50% of renal cell cancers present with haematuria as the tumour invades and bleeds into the renal collecting system. Other presentations may be due to distant effects of the tumour—polycythaemia due to tumour production of erythropoietin, or hypercalcaemia due to lytic bone metastases. A substantial proportion of cases are identified almost incidentally by ultrasonography or computed tomography while investigating a wide range of non-specific symptoms. This results in the diagnosis of many small tumours amenable to curative treatment, often conserving the rest of the kidney.

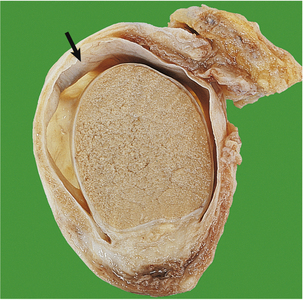

Appearances

Macroscopically, the kidney is distorted by a large tumour, found most often at the upper pole (Fig. 20.2). The cut surface reveals a solid yellowish-grey tumour with areas of haemorrhage and necrosis. The margins of the tumour are usually well demarcated, but some breach the renal capsule and invade the perinephric fat. Extension into the renal vein is sometimes seen grossly; occasionally, a solid mass of tumour extends into the inferior vena cava and, rarely, into the right atrium.

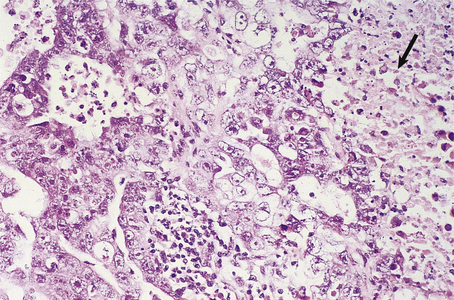

Microscopically there are distinctive different tumours with very different cytogenetic abnormalities (and by inference differing pathogenesis). Clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma has VHL gene abnormalities and is the largest group. Next is papillary renal cell carcinoma which has trisomies of chromosomes 7 and 17; this has papillary structures lined by cuboidal cells and is the variant associated with acquired cystic disease in renal failure. The third largest group is chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, which has large eosinophilic cells often similar to renal oncocytoma, a benign tumour.

Prognosis and treatment

Current overall 5-year survival rates in the UK are 50%. Prognosis worsens with increased stage (5-year survival rate of 10% for those with metastatic disease at presentation, but of 90% for early-stage disease) and increased age at presentation. Treatment is primarily by surgical excision, which is usually a complete nephrectomy. However, partial nephrectomy or local oblation by cryosurgery or other means is often done and conserves renal capacity. If the disease is metastatic there may still be some benefit in removing the primary tumour for control of local symptoms such as loin pain and haematuria. Renal cell carcinoma is not sensitive to conventional chemotherapy but there may be some response with interferon or newer oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sunitinib.

NEPHROBLASTOMA

Nephroblastoma (Wilms’ tumour) is a kidney tumour derived from embryonal tissue. It is rare, with 45 cases per year in the UK, and has a peak incidence between the ages of 1 and 4 years. Although it is usually biologically aggressive, often with lung metastases at presentation, combined chemoradiotherapy and surgery has improved the 5-year survival rate from 35% in the 1970s to over 80% at present. The Wilms’ tumour gene (WT1) has long been known to be abnormal in nephroblastoma, but the molecular mechanisms of this have still not been coherently elucidated.

CARCINOMA OF THE RENAL PELVIS

The renal pelvis is lined by transitional cell epithelium and so transitional cell carcinomas can arise at this site, accounting for 5–10% of all renal tumours. As they project into the pelvicalyceal cavity, they present early with haematuria or obstruction (Fig. 20.3). Their risk factors, histology and treatment are similar to those for transitional cell carcinomas of the ureters and bladder described below.

BENIGN RENAL TUMOURS

Renal oncoctyoma is composed of large eosinophilic cells, sometimes difficult to distinguish from renal cell carcinoma. Its imaging features also overlap with those of renal cell carcinoma, so, even though benign, is it usually diagnosed after surgical removal.

Angiomyolipoma typically has a combination of abnormal blood vessels, smooth muscle and adipose tissue. This gives it a characteristic radiological appearance, so small masses need not be resected; however, large masses have a risk of spontaneous haemorrhage. Some 20% of cases arise in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex, an inherited disorder involving the central nervous system, skin and other viscera.

URETERS

NORMAL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

The ureters form in continuity with the calyceal system and collecting ducts from an outgrowth of the Wolffian duct. Urine is conveyed to the bladder by peristaltic activity; this activity is reduced in pregnancy, predisposing to stasis and infection.

The lumen is lined by urothelium; the muscle layer is predominantly circular with a thin, inner longitudinal layer, and is invested in a fibrous adventitia. The ureteric orifice is slit-like, and the course of the terminal part of the ureter through the bladder wall is oblique to form a valve (see Fig. 21.14B, p. 591).

CONGENITAL LESIONS

A congenitally short terminal segment of the ureter, which is not oblique, results in vesico-ureteric reflux, an important cause of renal infection and scarring. Hydroureter is dilatation and often tortuosity of the ureter; this condition may occur as a congenital lesion, when it is thought to reflect a neuromuscular defect. The most frequent causes of hydroureter in the adult are low urinary obstruction and pregnancy.

OBSTRUCTION

Obstruction of the ureter is the most frequent problem requiring clinical attention. Acute ureteric obstruction causes intense pain known as renal colic. The consequences of chronic ureteric obstruction are hydroureter and hydronephrosis. In both acute and chronic ureteric obstruction there is an increased risk of ascending infection, causing pyelonephritis. Ureteric obstruction may be either intrinsic or extrinsic.

Intrinsic lesions are within the ureteric wall or lumen; the most common is a urinary calculus. Calculi become impacted where the ureter is normally narrowed, that is at the pelvi-ureteric junction, where it crosses the iliac artery, and where it enters the bladder. Strictures may be congenital, when they occur at the pelvi-ureteric junction or in the transmural terminal segment of the ureter. Acquired strictures occur as a result of trauma and involvement by adjacent inflammatory conditions such as diverticulitis and salpingitis. Severe haematuria may cause obstruction due to blood clot.

Extrinsic factors cause pressure from without, and include primary tumours of the bladder and rectum, metastatic carcinoma in pelvic lymph nodes and benign hyperplasia of the prostate. Aberrant renal arteries may compress the ureter. Retroperitoneal fibrosis causes narrowing and medial deviation of the ureters and may either be due to drugs, such as methysergide, or be idiopathic.

Primary tumours of the ureter are transitional cell carcinomas. They may be multiple and are associated with urothelial tumours in the renal pelvis and bladder.

BLADDER

NORMAL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

The urinary bladder is a cavity lined by transitional cell epithelium—the urothelium, surrounded by connective tissue—the lamina propria, and smooth muscle. Histologically, the normal bladder urothelium is seven to eight cells thick and has three zones: basal, intermediate and a surface layer of umbrella cells. The smooth muscle is arranged in bundles that interlace rather than form defined layers. Urine drains into the bladder from the kidneys, via the ureters, for storage until a convenient time and place is found for its discharge through the urethra. The bladder responds to obstruction to the outflow by undergoing muscular hypertrophy. The proximity of the bladder to the genital tract in females, to the prostate in males, and to the bowel in both sexes, means that it is often invaded by tumours arising in, or affected by other changes in, these nearby organs.

DIVERTICULA

Diverticula are outpouchings of the bladder mucosa. Bladder diverticula are either congenital or acquired. They are clinically important because urinary stasis within them predisposes to calculus formation and infection.

Congenital diverticula are usually solitary. They arise from either a localised developmental defect in the muscle or urinary obstruction during fetal life.

Acquired diverticula are small and multiple. They are most often associated with outflow obstruction, and the high incidence in elderly males correlates with prostatic enlargement. They occur between the bands of hypertrophic muscle, known as trabeculae, which form in response to obstruction.

CONGENITAL LESIONS

Exstrophy of the bladder is a serious developmental defect affecting the anterior abdominal wall, bladder and, in some cases, the symphysis pubis. The bladder opens directly on to the external surface of the lower abdomen. Infection and pyelonephritis, together with a predisposition to adenocarcinoma, are important sequelae.

Vesico-ureteric reflux (VUR) is an important consequence of a developmental abnormality of the terminal part of the ureter that appears to correct itself as the patient matures. However, during early childhood reflux occurs, which results in substantial scarring of the renal parenchyma. This condition is an important cause of renal impairment and infection in adult life.

Persistence of the urachus may be partial or complete. Retention of the entire structure results in a fistula connecting the bladder with the skin at the umbilicus. Partial retention results in a diverticulum arising from the dome of the bladder. Alternatively the central area may persist and present as a cyst. Adenocarcinomas may develop in these urachal remnants.

CYSTITIS

Inflammation of the bladder (cystitis) is a common occurrence as part of a urinary tract infection. The causative organism is usually derived from the patient’s faecal flora. Unusual organisms do occur; for example, Candida is seen in patients on prolonged antibiotic therapy, and tuberculous cystitis almost always reflects tuberculosis elsewhere in the urinary tract. Radiation and trauma due to instrumentation cause cystitis, which is often sterile.

Cystitis presents with frequency, lower abdominal pain and dysuria (scalding or burning pain on micturition), and occasionally haematuria. In some patients there is general malaise and pyrexia. Cystitis usually responds readily to treatment. However, its clinical importance lies in the predisposition to pyelonephritis, a serious complication.

Schistosomiasis causes a granulomatous cystitis, in which the parasite ova are demonstrable; it is notable for the increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma.

BLADDER CALCULI

Diverticula, obstruction and inflammation are all important in the development of stones within the bladder. Alternatively, calculi may be passed down the ureter from the kidney. Bladder stones may be asymptomatic, but eventual chronic irritation and infection lead to frequency, urgency, dysuria and sometimes haematuria. There is an increased risk of bladder carcinoma; this is often of squamous type, arising from metaplastic squamous epithelium.

TUMOURS OF THE BLADDER

In Europe and North America, transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder accounts for 90% of bladder tumours

In Europe and North America, transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder accounts for 90% of bladder tumours Risk factors include cigarette smoking and exposure to chemicals such as aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

Risk factors include cigarette smoking and exposure to chemicals such as aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbonsTRANSITIONAL (UROTHELIAL) CELL CARCINOMA OF THE BLADDER

Incidence

Transitional cell carcinoma accounts for 90% of bladder cancer in North America and Europe. In the UK about 10 500 new cases are diagnosed each year, 4% of all cancers, with around 5000 deaths a year. The incidence in the UK is gradually decreasing from a peak in the early 1990s. There is a male:female ratio of 5:2. Transitional cell bladder cancer is rare before the age of 50 years and the peak incidence occurs between the ages of 70 and 80 years.

Predisposing factors

Tobacco smoking and occupational exposures are the main environmental risks for transitional cell bladder cancer. On average, current smokers have a 300% increased risk and about 50% of all transitional cell bladder cancers can be attributed to smoking. This risk is due to the absorption of aromatic amines from cigarette smoke and their excretion in the urine. Aromatic amines have historically been present in industrial processes used to produce dyes, drugs and rubber, and a significant amount of bladder cancer could be attributed to industrial exposure to these chemicals. Most of these compounds were withdrawn from these processes in the 1950s, but there was a lag phase of new cancers developing from this exposure. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons is a risk factor and these by-products of combustion are present in many industrial processes. It is estimated that 4% of European bladder cancer cases are due to this exposure, and this effect might be higher in countries with less regulated industries.

Genetic risk factors fall into two groups: genetic deficiencies of enzymes that would otherwise metabolise chemicals that are risk factors for bladder cancer (e.g. N-acetyl transferase), and genetic alterations in the tumours themselves. Although an oversimplification, there are two distinct genetic patterns in urothelial carcinoma. Papillary superficial tumours have relatively few and stable abnormalities. In contrast, solid invasive tumours have different alterations and tend to accumulate multiple abnormalities as they progress. However, molecular or genetic testing is not yet sufficient for diagnosis or follow-up.

Presentation

Some 80% of transitional cell bladder cancers present with painless haematuria. Other presenting symptoms may include urinary frequency and pain on micturition.

Appearances

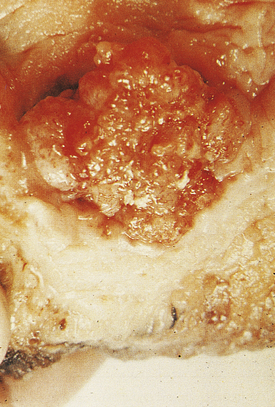

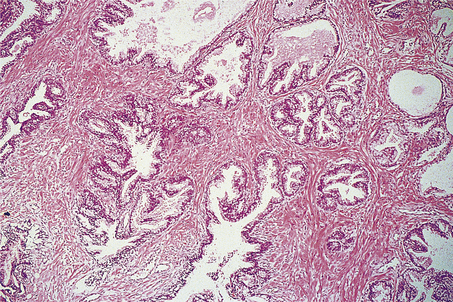

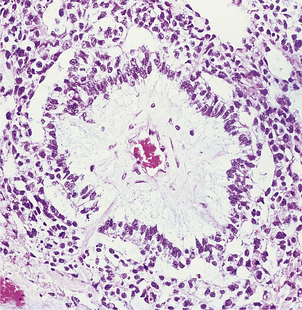

At presentation most bladder tumours are low-grade and papillary, with fronds lined by a slightly thickened urothelium showing little cytological abnormality (Fig. 20.4). Usually there is no invasion of the lamina propria. Papillary tumours are frequently multiple, consistent with a widespread field change throughout the urothelium including the upper tract, even though it is histologically normal.

Fig. 20.4 Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. These common tumours usually project into the bladder lumen before invading the underlying bladder wall.

In contrast, about 20% of tumours are solid and invasive at presentation extending into the detrusor muscle, and if beyond they render the tumour fixed clinically. These tumours are high grade with marked cytological abnormalities; aberrant squamous or adenocarcinoma differentiation may be seen, and there are other histological variants too. The background urothelium often shows carcinoma in situ, which is considered to be the precursor lesion, and may give rise to further high-grade invasive tumours.

Between these two extremes of tumour type there are some high-grade papillary tumours; these may have background carcinoma in situ, and are more likely to progress to invasive carcinoma.

Prognosis and treatment

Prognosis is closely related to the stage of the tumour. Superficial tumours (without muscle invasion) can be removed by transurethral resection and have an excellent prognosis. These patients are likely to have a field change and so require regular follow-up cystoscopy as about 70% of patients will develop further tumours. Progression to more invasive tumours occurs in around 20% of patients. Intra-vesical treatment with BCG or chemotherapy can be used for multiple superficial tumours or carcinoma in situ. Tumours which have invaded muscle require more intensive therapy. A radical cystectomy will remove the tumour and all the dysplastic bladder epithelium but it is a large operation which results in the patient having an ileal bladder, either isotopic or with a stoma. Radiotherapy is another possible treatment modality.

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA OF THE BLADDER

As the bladder is normally lined by transitional epithelium, squamous cell carcinoma can arise only from metaplastic squamous epithelium in the bladder. This metaplasia commonly occurs with chronic infection with schistosome parasites. In countries where schistosomiasis is endemic, such as Egypt, squamous cell bladder cancer is the most common tumour in men, presenting in the fifth decade, usually at a more advanced tumour stage with corresponding worse prognosis. Long-term catheterisation following paraplegia carries similar risks.

PROSTATE GLAND

NORMAL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

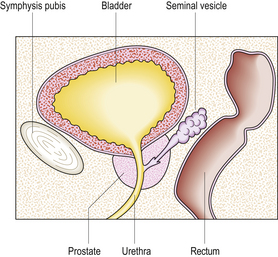

The prostate gland surrounds the bladder neck and proximal urethra (Fig. 20.5). It consists of five lobes, separated by the urethra and ejaculatory ducts. Two lateral lobes and an anterior lobe enclose the urethra. The two lateral lobes are marked by a posterior midline groove, palpable on rectal examination. The middle lobe lies between the urethra and ejaculatory ducts and the posterior lobe lies behind the ejaculatory ducts. The normal gland weighs about 20g and is enclosed in a fibrous capsule.

Fig. 20.5 Male pelvic organs. Sagittal section showing that the prostate can be palpated easily by inserting a finger into the rectum.

From a pathology perspective, it is more useful to divide the prostate into zones. In early adult life the peripheral zone accounts for 70% of the organ, the transition zone (both sides of the proximal urethra) 5% and the central zone 20%. Prostate cancers arise almost exclusively from the peripheral zone. The transition zone gradually enlarges with age, and is the site of considerable enlargement in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Concentric groups of glands in all zones converge on ducts and open in the urethra.

Individual glandular acini have a convoluted outline, the epithelium varying from cuboidal to a pseudostratified columnar cell type depending upon the degree of activity of the prostate and androgenic stimulation. The epithelial cells produce prostate-specific antigen (PSA), acid phosphatase and the prostatic secretion that forms a large proportion of the seminal fluid for the transport of sperm. The normal gland acini often contain rounded concretions of inspissated secretions (corpora amylacea). The acini are surrounded by a stroma of fibrous tissue and smooth muscle.

The blood supply to the prostate gland is from the internal iliac artery by the inferior vesical and middle rectal branches. The prostatic veins drain to the prostatic plexus around the gland and then to the internal iliac veins. The nerves are from the pelvic plexus.

INCIDENCE OF PROSTATIC DISEASE

Diseases of the prostate are common causes of urinary problems in men, the incidence of which increases with age, particularly beyond 60 years. Most prostatic diseases cause enlargement of the organ resulting in compression of the intraprostatic portion of the urethra; this leads to impaired urine flow, an increased risk of urinary infections, and, in some cases, acute retention of urine requiring urgent relief by catheterisation. The most important and common causes of these signs and symptoms are prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic carcinoma. Inflammation of the prostate gland—prostatitis—is also common, but it less often gives rise to serious clinical problems; indeed, small foci of prostatic inflammation are not uncommon coincidental findings in prostatic tissue removed because of hyperplasia or carcinoma.

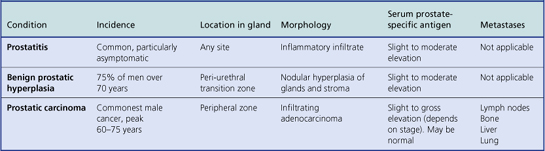

The principal clinicopathological features of the common types of prostatic pathology are compared in Table 20.1.

PROSTATITIS

Prostatitis means inflammation of the prostate; however, it is a confusing subject because of the substantial lack of correlation between the clinical symptoms, detection of neutrophils in prostatic secretions and an inflammatory infiltrate in histological samples. A causative organism is found in only 5–10% of cases; symptoms overlap with those of benign prostatic hyperplasia. The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) has published a consensus categorisation of prostatitis, and also a chronic prostatitis symptom index to tighten up clinical diagnosis:

In addition, there are patients with granulomatous inflammation of the prostate.

Category I: Acute bacterial prostatitis

Patients will be ill and febrile, and have difficulty with voiding, dysuria, frequency and urgency. On palpation the prostate is firm, indurated and tender. The usual cause is Escherichia coli, and infection may follow instrumentation. The glands and adjacent stroma show neutrophil infiltration, which may progress to an abscess.

Category II: Chronic bacterial prostatitis

This may follow inadequately treated acute prostatitis; the symptoms are similar, though the patients are not so ill. The causative organism can be cultured from appropriate specimens.

Category III: Chronic pelvic pain syndrome

The presence or absence of neutrophils in specimens distinguishes the subtypes. Symptoms may relate to urination or there may be pain on ejaculation. No organisms can be cultured by usual methods, so the causes are uncertain. However, bacterial DNA has been detected in patients, and some respond to prolonged antibiotic treatment, so infection by novel pathogens is a plausible cause.

Category IV: Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis

Though patients have no symptoms, leukocytes or bacteria are identified from investigations. About 70% of biopsies taken for the investigation of possible cancer show an inflammatory cell infiltrate at least focally.

Granulomatous prostatitis

Granulomatous prostatitis is a heterogeneous group of lesions, all of which may cause enlargement of the gland and urethral obstruction. The inflammatory component and associated fibrosis produce a firm, indurated gland on rectal examination which may mimic a neoplasm clinically, thus highlighting the importance of correctly diagnosing this uncommon group of conditions.

Idiopathic prostatitis may result from leakage of material from distended ducts in a gland enlarged by nodular hyperplasia. There is a periductal inflammatory infiltrate which includes macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes and plasma cells, with associated fibrosis.

The prostate is often involved in cases of genito-urinary tuberculosis. This condition is usually secondary to tuberculous cystitis or epididymitis, the infection spreading along the prostatic ducts or vas deferens. The histological features are of caseating granulomas distributed among the prostatic glands and through the stroma.

Some patients may require a second transurethral resection for benign nodular hyperplasia or carcinoma if the first operation fails to relieve the obstructive symptoms. The second biopsy often contains granulomas with necrosis; this lesion may be ischaemic, related to damaged blood vessels.

BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the histological basis of a non-neoplastic enlargement of the prostate gland, benign prostatic enlargement (BPE), which occurs commonly and progressively after the age of 50 years. About 75% of men aged 70–80 years are affected and develop variable symptoms of urinary tract obstruction, benign prostatic obstruction (BPO). If severe and untreated, the hyperplasia may lead to recurrent urinary infections and, ultimately, impaired renal function.

Aetiology

The glands and stroma of the transition zone proliferate, sometimes substantially. The driver is dihydrotestosterone, which is derived from testosterone by the action of 5-alpha reductase, acting via testosterone receptors; after binding, the complex relocates to the nucleus to bind to DNA where it acts as a gene transcription regulator to promote growth, cell survival and other functions. The underlying cause is not known, but there is some evidence to suggest that persistent inflammation results in the secretion of growth-promoting cytokines. As well as the increased bulk of the prostate gland around the urethra, the smooth muscle tone, mediated via alpha-adrenergic receptors, may make a significant contribution to the symptoms. Although benign prostatic hyperplasia is not premalignant, there are some epigenetic abnormalities, particularly gene methylation, and the gene expression profile is different from normal.

Morphology

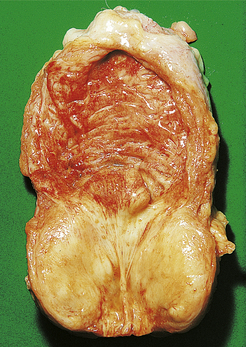

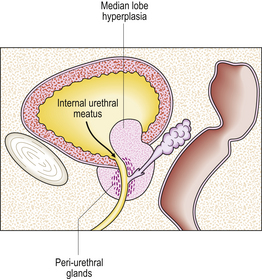

The hyperplastic process usually involves both lateral lobes of the gland. In addition, there may be a localised hyperplasia of peri-urethral glands posterior to the urethra and projectinginto the bladder adjacent to the internal urethral meatus (Fig. 20.6). This hyperplasia is described as ‘median’ lobe enlargement but does not correspond to the anatomical middle lobe.

Fig. 20.6 Prostatic hyperplasia. Sagittal section showing the hyperplastic median lobe protruding into the bladder.

The cut surface of the enlarged prostate shows multiple circumscribed solid nodules and cysts (Fig. 20.7). Histological examination reveals two components: hyperplasia both of glands and of stroma. The acini are larger than normal (some may be cystic) and are lined by columnar epithelium covering papillary infoldings (Fig. 20.8). The acini may contain numerous corpora amylacea. Phosphates and oxalates may be deposited around these to form prostatic calculi.

Fig. 20.7 Prostatic hyperplasia. The prostatic lobes are symmetrically enlarged and nodular. The bladder mucosa has a trabecular pattern due to hypertrophy of the underlying muscle bundles.

Fig. 20.8 Prostatic hyperplasia. The acini are lined by columnar epithelium with numerous infoldings. The muscular stroma is abnormally abundant.

The stromal hyperplasia includes both smooth muscle and fibrous tissue. Some of the nodules are solid, being composed predominantly of stroma, and others also contain hyperplastic acini. Stromal oedema and periductal inflammation are common and may contribute to the urinary obstruction. Areas of infarction commonly occur, evident as yellowish necrotic areas with a haemorrhagic margin; these may result from obstruction to the blood supply by the hyperplastic nodules. There is often squamous metaplasia of prostatic ducts and acini at the edges of the infarct. Benign nodular hyperplasia is not a premalignant lesion.

Clinical features

There are four main factors in the development of obstructive symptoms:

The resulting obstruction to the bladder outflow produces various lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), which can be grouped as bladder sensation symptoms, storage symptoms and voiding symptoms; these have been incorporated into an International Prostate Symptom Score. Bladder sensation may be normal, increased or decreased. Storage symptoms include daytime frequency, nocturia, urgency and incontinence. Voiding symptoms include hesitancy, poor or intermittent stream, straining and dribbling.

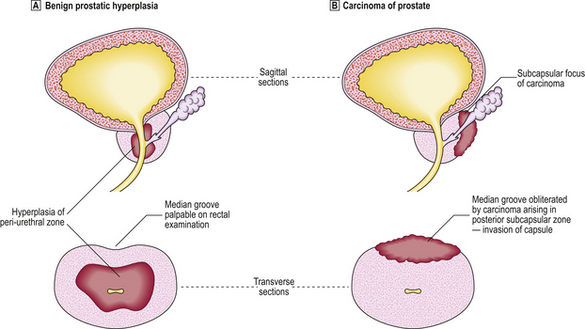

Digital examination of the gland per rectum reveals enlargement of the lateral lobes, often asymmetrical. The gland has a firm, rubbery consistency, and the median groove is still palpable.

Acute urinary retention may develop in a man with previous LUTS; the bladder is palpably enlarged and tender, requiring catheterisation. This condition may be precipitated by voluntarily withholding micturition for some time, by recent infarction causing sudden enlargement of a hyperplastic nodule, or by exacerbation of local inflammation.

Chronic retention of urine is relatively painless. There may be increasing frequency and overflow incontinence, usually at night. The bladder is distended, often palpable up to the umbilicus, but is not tender since the distension is more gradual.

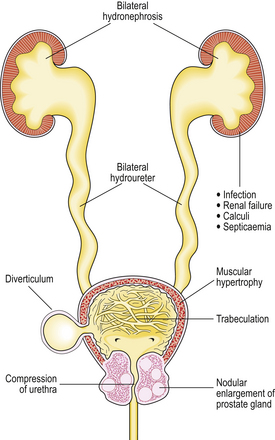

Complications

Continued obstruction of the bladder outflow results in gradual hypertrophy of the bladder musculature. Trabeculation of the bladder wall develops due to prominent bands of thickened smooth muscle between which diverticula may protrude. This compensatory mechanism eventually fails, with resulting dilatation of the bladder. The ureters gradually dilate (hydroureter), allowing reflux of urine; if untreated, bilateral hydronephrosis may develop, with dilatation of renal pelvis and calyces (Fig. 20.9).

As the bladder fails to empty completely after micturition a small volume of urine remains in the bladder. This residual urine is liable to infection, usually by coliform organisms. The resulting cystitis is characterised by painful micturition with increased frequency and haematuria. An ascending infection in the presence of an obstructed urinary tract may result in pyelonephritis and impaired renal function. Repeated infections predispose to the development of calculi, often containing phosphates, within the bladder. Septicaemia may complicate pyelonephritis.

Clinical diagnosis and management

A careful history of LUTS in the usual basis for a diagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Further investigation may include:

Serum PSA may be elevated in benign prostatic hyperplasia, but this is not usually used in the diagnosis or assessment of it, but rather as an explanation of elevated PSA after prostate cancer has been excluded.

Many patients will not be sufficiently troubled by their symptoms to request treatment. For those that are, pharmacological interventions are the usual initial treatment, using alpha-adrenergic blockers (to reduce smooth muscle tone) or 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (to reduce dihydrotestosterone drive). Anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics may also be appropriate.

Some patients will require surgical intervention, typically transurethral resection of the hyperplastic prostate tissue. Multiple other methods of selective tissue destruction are possible including heat (using microwaves or other media), lasers, electromagnetic radiation and ultrasound.

IDIOPATHIC BLADDER NECK OBSTRUCTION

Idiopathic bladder neck obstruction, an uncommon obstructive lesion at the bladder outlet, usually occurs in young men. Its cause is unknown. A prominent transverse ridge develops at the internal urethral meatus, resulting from a localised hypertrophy of smooth muscle.

The clinical symptoms are similar to those of benign nodular hyperplasia. As the pathological lesion is very localised, the gland is not palpably enlarged on rectal examination. Treatment is by bladder neck incision.

PROSTATIC CARCINOMA

Carcinoma of the prostate is one of the commonest forms of malignant disease and is the second leading cause of male death from malignancy in Europe and the USA. The UK incidence has increased during the last two decades to about 93 per 100000 males, giving about 29000 new cases, and 9000 deaths in 2005 in England (13% of male cancer deaths). The tumour is rare below 50 years of age; the peak incidence is between 65 and 75 years. From these data it is apparent that prostate cancer is a substantial burden of disease with many deaths, though many men are cured. However, there are also many people who require no treatment, who in retrospect have only the disadvantages and none of the benefits of making the diagnosis.

Aetiology

The aetiology of prostatic carcinoma is unknown, although a substantial proportion are dependent on androgens. Most tumours arise in the peripheral zone, though intriguingly this zone also undergoes some involution with advancing age. A family history of the disease is relevant: there is a two- to three-fold risk of the tumour developing in men with a first-degree relative in whom prostatic carcinoma was diagnosed at under 50 years of age. There is a three-fold risk for African or Caribbean men compared to whites; the risk in China and Japan is lower. Some dietary studies have shown possible associations, but these do not fully explain the racial difference.

The molecular genetic basis of prostate cancer is complex, and so far lacks clinical application. Benign prostatic hyperplasia is not considered a pre-neoplastic lesion although it is often found coincidentally in the same gland as a carcinoma, as both lesions are common. Operations for hyperplasia do not remove the peripheral zone, so carcinoma can arise after such a ‘prostatectomy’ (Fig. 20.10).

Fig. 20.10 Prostatic hyperplasia versus carcinoma.  Hyperplasia commonly affects the peri-urethral zone.

Hyperplasia commonly affects the peri-urethral zone.  In contrast, most carcinomas are peripheral.

In contrast, most carcinomas are peripheral.

Pathology

There may be very little to see on macroscopic examination, particularly for organ-confined disease, though sometimes the tumour is slightly yellow. Locally advanced disease may be more obvious, with invasion of the seminal vesicles or bladder, or fixation to the pelvic wall.

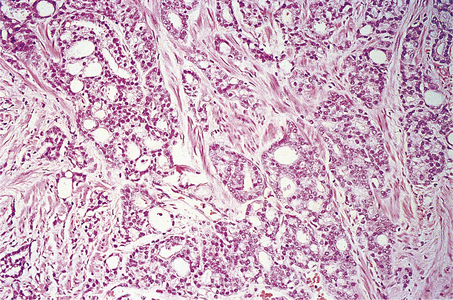

The great majority of tumours are adenocarcinoma, often described as microacinar, though much variety of histological pattern is recognised, and the tumours often show more than one pattern. Rare subtypes include an aggressive small cell carcinoma, which is similar to small cell lung cancer (Ch. 14), and large duct carcinoma, which arises centrally from the large ducts; these are not discussed further.

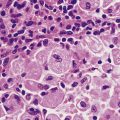

The Gleason grading system describes the usual patterns taken by the tumour. Gleason pattern 3 is the commonest pattern, and comprises separated, somewhat irregular, gland or acinar profiles, that infiltrate into normal glands at the edge of the mass. Gleason pattern 4 has fused glands or cribriform structures (Fig. 20.11), while in pattern 5 acinar differentiation is no longer apparent in strands of tumour cells, or there may be cribriform structures with central necrosis. It is now widely acknowledged that Gleason pattern 1 is probably not carcinoma, while pattern 2 is a generally small, well-circumscribed mass of regular glands; it is of limited clinical significance. The grading system is to note the dominant (primary) pattern and add the next most frequent (secondary) pattern to give a combined score; where only one pattern is seen (as often applies in a small biopsy) the number is doubled. Thus, the majority of prostate cancers are graded as Gleason 3+3=6; many are Gleason 3+4=7, while a particularly aggressive tumour would be Gleason 5+5=10.

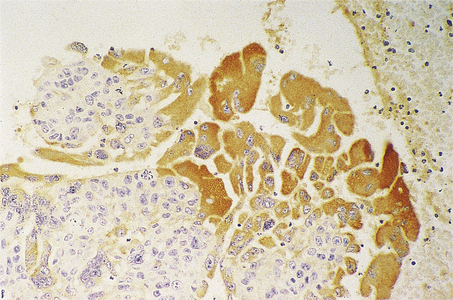

Fig. 20.11 Histology of prostatic carcinoma. The tumour is an adenocarcinoma consisting of neoplastic glands infiltrating a fibrous stroma.

Prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia (PIN)

This is a common precursor lesion which may be present for many years before invasive carcinoma develops, if ever. Like carcinoma in situ at other sites, it comprises cytologically malignant cells confined within the ductal system, with no invasion of stroma. If PIN is discovered in a biopsy it is not yet clear what the management should be—whether to re-biopsy or when.

Mode of spread

Spread of prostatic carcinoma may be:

Direct spread

Direct spread of the prostatic tumour occurs both within the gland and to extracapsular adjacent structures. There is invasion of the prostatic stroma towards the peri-urethral tissues and the base of the bladder is also commonly involved. Extension through the prostatic capsule is common, involving the seminal vesicles. The rectal wall is rarely invaded, being protected by the recto-vesical fascia. This extracapsular invasion results in the prostate becoming fixed to adjacent tissues.

Spread via lymphatics

Lymphatics provide an important route of dissemination of prostatic carcinoma, producing metastases in the sacral, iliac and para-aortic nodes. These may result in lymphatic obstruction and oedema of the legs. Less often, the inguinal nodes are involved.

Spread via blood

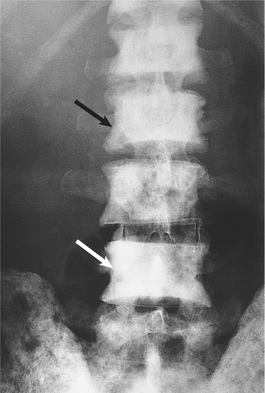

Vascular invasion by the tumour results in blood-borne metastases, most commonly to bone, lungs and liver. The most frequent sites of bone metastases are the pelvis, lumbosacral spine and proximal femur, less frequently the ribs and skull. Tumour emboli may reach the vertebrae by venous spread to the lung, then by passing through the pulmonary capillaries to enter the arterial circulation. An alternative mechanism is by retrograde venous spread through the vertebral venous plexus, because the blood flow in these veins may reverse due to physiological variation in the intra-abdominal pressure.

Bone metastases are usually osteosclerotic, with proliferation of osteoblasts and areas of new bone formation occurring in association with the neoplastic cells (Fig. 20.12). The osteoblast proliferation results in a raised serum alkaline phosphatase level.

Clinical features

The clinical presentation and features of prostatic carcinoma include:

Many men are unaware of their prostate cancer, or may have a tumour diagnosed and remain asymptomatic. This situation can last for years. Other men have a tumour that will progress and is potentially fatal.

Urinary outflow obstructive symptoms caused by prostatic carcinoma usually progress more rapidly than those due to benign hyperplasia.

Digital rectal examination is a very important clinical procedure, revealing a hard nodule of tumour in the posterior lobe; the induration is due to the fibrous stromal reaction to the adenocarcinoma cells. The gland may be enlarged. If capsular invasion has occurred, the capsule is irregular and the median groove is obliterated. Less often, the rectal mucosa is fixed to the prostate. Induration may, however, be due to a non-neoplastic lesion such as prostatic calculi or granulomatous prostatitis. With many small tumours there is no palpable abnormality. Many patients will have benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Bone metastases often present as localised bone pain, back pain from vertebral metastases being a common initial manifestation of the tumour. Pathological fracture is another clinical presentation. Anaemia may result from extensive neoplastic infiltration of several bones with replacement of haemopoietic tissue.

Finally, peripheral lymphadenopathy due to metastatic carcinoma is occasionally the initial presentation.

Diagnosis

There are four common ways to diagnose localised or non-metastatic prostate cancer:

With symptomatic men, all four modalities are likely to be used. With or without a palpable abnormality it will be usual to take blood for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) estimation. If this is elevated the patient will be offered needle biopsy under transrectal ultrasonographic guidance. It is rare for there to be a lesion to target on biopsy, so usually a standard set of 10 to 12 cores is taken from all accessible parts of the gland, preferentially sampling the periphery. If adenocarcinoma is found, it is possible to get an estimate of the Gleason grade and extent of tumour. If no tumour is found it is necessary to discuss with the patient whether to repeat the biopsy series after a short interval or to monitor serum PSA pending further decisions.

With asymptomatic men the situation is rather different. It is important to discuss with the man the merits and disadvantages of being investigated, to enable him to make choices that fit his lifestyle priorities.

Prostate-specific antigen

PSA is a glycoprotein produced by prostate epithelium which has a physiological role in the liquefaction of semen. Normally, very little is detectable in serum; however, prostatic inflammation, hyperplasia and neoplasia can all result in elevated levels. As a consequence, serum levels tend to rise with age, probably reflecting hyperplasia, and may fluctuate in a short time frame, presumably reflecting inflammation. There is no threshold value below which cancer is excluded, or above which cancer is likely. Taking values in the range 4–10 ng/ml, only 30% of men will have prostate cancer detected on biopsy, but 15% of men tested with a PSA value below 4 ng/ml will have cancer; occasional prostate cancers do not secrete PSA.

Further investigations

Further investigations include:

Patients considered for curative treatment will usually have MRI of the pelvis, looking for evidence of lymph node metastasis and locally advanced disease with invasion beyond the prostate. If the PSA is above 10 ng/ml an isotope bone scan will be offered to seek evidence of skeletal metastasis. With widespread carcinomatous infiltration of the bone marrow a leukoerythroblastic anaemia develops, evinced by the presence of primitive red and white cell precursors in the peripheral blood (Ch. 23). If routine blood tests suggest renal impairment, then causes such as ureteric obstruction by the tumour will need to be investigated.

The diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer will depend upon the presenting symptoms. Pain or fracture related to skeletal metastases is investigated radiologically, with biopsy as appropriate. Immunohistochemical staining for PSA would confirm origin from the prostate.

Clinical management

There are many challenges in the management of prostate cancer, and much uncertainty about what is best. This is a brief outline of some of these issues. Expert counselling of the man is critically important.

Initiating diagnostic tests

As alluded to above, whether to embark on a diagnostic pathway or whether to perform a needle biopsy cannot be assumed. Whilst many men will benefit, some will be disadvantaged, so the issues must be discussed.

Localised prostate cancer

At diagnosis about 70% of men will have the cancer apparently confined to the prostate gland. Though these men are potentially curable by local treatment (surgery or radiotherapy), not all will benefit from treatment. The issue is that some tumours grow slowly and remain asymptomatic, so the person eventually dies with their tumour, but not from it; radical treatment in this situation gives the risks and potential morbidity, but not the benefit. However, identifying such indolent or low- risk tumours cannot, at present, be done at diagnosis with sufficient accuracy. So if after discussion a man elects not to proceed directly to radical treatment, but does not wish to abandon the possibility later, it would be essential to monitor the situation; the window of opportunity for curative treatment may close, leaving only palliative options.

Those tumours that are localised but of a higher Gleason score or higher PSA are still potentially curable, so radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy are the usual treatment options offered; discussion is again important as the morbidity varies with the treatment.

Locally advanced prostate cancer

About 20% of cases present with disease no longer confined to the prostate, but still within the pelvis. Curative surgery is not likely to be an option; radiotherapy has a place. The mainstay of treatment is hormone manipulation to reduce the androgen tumour drive. This can be by removing the supply of androgens or by androgen receptor blockade (e.g. bicalutamide), or a combination of both.

Androgen withdrawal can be achieved by pharmacological means such as luteinising hormone-releasing hormone agonists (LHRHa), or surgically by bilateral orchidectomy. Historically, Huggins in Chicago introduced oestrogens in 1941 for the same purpose.

Metastatic prostate cancer

About 10% of patients present with disseminated cancer. Hormone treatment is the usual way forward, as above. There is also a role for bisphosphonates in the management of bone metastases, though the specific indications are still contentious.

Hormone refractory disease

There is a general tendency for prostate cancer eventually to escape from androgen dependency as the disease progresses, often as a result of mutations in the androgen receptor gene. Initially changes to the method of androgen deprivation being used may help; eventually only chemotherapy remains as an option and has limited success.

Screening and prevention of prostatic cancer

With the current tests available and level of knowledge, the criteria for population cancer screening are not met. Though PSA is widely used for case detection, it has serious shortcomings because of the absence of a reliable threshold between tumour and non-tumour bearers, as outlined above. There is also the major uncertainty about how to manage incidentally discovered cancers. However, as the prostate is dependent on dihydrotestosterone there have been studies showing that 5-alpha reductase inhibitors reduced the incidence, though this can be considered only in specific high-risk individuals, for example those with a strong family history.

PENIS AND SCROTUM

Diseases affecting the penis, ranked in order of frequency, are:

It is common practice to examine carefully the external genital region of male neonates to detect major malformations; minor abnormalities may remain undetected until the prepuce can be fully retracted. In adolescents and adults, sexually transmitted infections (e.g. gonorrhoea) constitute a major public health problem in many countries; the penis is also one route of transmission of other serious infections, notably HIV—the cause of AIDS. The commonest tumours are benign warts, occurring usually in young adults; carcinomas are relatively uncommon.

CONGENITAL LESIONS

Congenital lesions of the penis and scrotum include:

Hypospadias

Hypospadias is the commonest congenital abnormality of the male urethra, resulting from a failure of fusion of the urethral folds over the urogenital sinus. Normal fusion of these folds starts at the posterior end and extends forward along the penile shaft to the tip. If fusion is incomplete, the urethra does not reach the tip of the penis, but opens on to its inferior aspect. The commonest site is a meatus on the inferior aspect of the glans. Less often, the meatus is on the penile shaft, and is associated with a downward curvature of the penis (congenital chordee). Rarely, there is a complete hypospadias with the urethral opening on the perineum behind the scrotum.

Epispadias

The congenital abnormality epispadias is much less common than hypospadias. The urethra opens on to the dorsum of the penis, the commonest site being at the base of the shaft near the pubis. This lesion results in urinary incontinence and infections. Epispadias is sometimes associated with exstrophy of the bladder.

INFLAMMATION AND INFECTIONS

Balanoposthitis

Inflammation of the inner surface of the prepuce (posthitis) is usually accompanied by inflammation of the adjacent surface of the glans penis (balanitis). Such a balanoposthitis is often associated with a tight prepuce (phimosis). Sebaceous material and keratin may accumulate beneath the prepuce, which may become infected by pyogenic bacteria. These bacteria include staphylococci, coliforms or gonococci. In diabetic patients, Candida infection is a further risk.

There is redness and swelling of the prepuce and glans with an associated purulent exudate. If treatment is delayed or there are recurrent episodes of infection, fibrous scarring can occur with the formation of preputial adhesions or severe phimosis.

Phimosis

Phimosis, and the closely related condition of paraphimosis, are the commonest medical indications for male circumcision.

In phimosis, the prepuce cannot be retracted over the glans penis. In most cases this is an acquired lesion, being the late sequel of an ammoniacal preputial dermatitis in infancy. Ammonia is formed by the action of some bacteria on the urine, producing blisters over the glans and inner aspect of the prepuce. This blistering results in the formation of numerous minute skin ulcers with associated acute inflammation and eventual fibrosis, narrowing the opening in the prepuce.

Paraphimosis

If a tight prepuce is retracted behind the glans it may obstruct the venous return from the glans and prepuce. The resulting oedematous swelling of the glans and prepuce produces a paraphimosis in which the prepuce cannot be returned easily to its normal position.

Balanitis xerotica obliterans

Balanitis xerotica obliterans is an uncommon penile lesion characterised by thickened white plaques and fissures on the glans and prepuce. The symptoms are of a non-retractile prepuce or preputial discharge, often necessitating circumcision. Similar lesions may develop around the urethral meatus with resulting scarring. The condition most commonly affects men aged 30–50 years.

The histological features are of hyperkeratosis and atrophy of the epidermis with basal layer degeneration. The papillary dermis shows hyalinisation of the collagen with an underlying infiltrate of lymphoid cells. Similar changes are seen in lichen sclerosus of the vulval skin; some people thus also refer to the penile lesion as lichen sclerosus.

Genital herpes

Aetiology

Herpes is an acute infectious disease caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV). There are two antigenic types of the virus: HSV types 1 and 2. Most genital tract lesions are caused by type 2 as a sexually transmitted disease. HSV type 2 produces a recurrent, acute vesicular eruption on the skin, usually around the mouth or on the genitalia. The incidence of genital herpes is increasing.

The majority of primary herpes infections are subclinical, but sometimes there is a febrile illness followed by the vesicles; following this initial infection the virus may remain latent for many years. The virus may remain either locally in the skin or in the nerve ganglion supplying that skin segment, by migrating along the axons to the ganglia. Recurrent herpes infections are caused by reactivation of the virus and may be precipitated by a febrile illness, immune suppression, emotional stress or by ultraviolet light.

Clinicopathological features

The primary lesion of herpes genitalis in the male is preceded by itching followed by the appearance of several closely grouped vesicles surrounded by erythema on the glans penis or the coronal sulcus. The acute skin lesion is an intra-epidermal vesicle with evidence of cellular damage associated with the virus. There may be vacuolation of the epidermal cells, some of which are multinucleated and contain viral inclusions. The vesicles soon burst to produce shallow painful ulcers. Less often, there is a more diffuse balanitis which may heal with a resulting phimosis, and occasionally vesicles develop on the shaft of the penis or on the scrotum. Herpetic lesions are less common in circumcised men. In some patients, the infection is asymptomatic with no visible lesions, although these patients may still transmit the disease.

The clinical features may be sufficient to enable a diagnosis but laboratory confirmation can be obtained by isolation of the virus from vesicular fluid. A swab or scrape from this source, collected in a suitable viral transport medium, can be used to demonstrate a cytopathic effect in tissue culture. Viral particles may also be identified by examining vesicle fluid by electron microscopy. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to identify viral DNA is rapid, and has a high diagnostic yield.

Genital warts

Genital warts are increasing in prevalence and are now probably the commonest type of lesion seen in patients attending departments of genito-urinary medicine.

Aetiology

Genital warts are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), a DNA virus of the papovavirus group. The HPV types causing genital warts (HPV 6 and 11) differ from those causing the common skin wart (HPV 1, 2 and 4). HPV types 16 and 18 are incriminated in the aetiology of squamous carcinoma of the penis, and also cervical cancer (Ch.19).

Clinicopathological features

In the male, the characteristic lesion is a hyperplastic, fleshy wart or condyloma acuminatum. This wart occurs most commonly on the glans penis and inner lining of the prepuce or in the terminal urethra. Less often, lesions develop on the shaft of the penis, the peri-anal region or the scrotum.

Histologically, the epidermis shows papillomatous hyperplasia. Many of the epidermal cells show cytoplasmic vacuolation, a feature indicating a viral aetiology. There is no epidermal dysplasia and these lesions are not premalignant.

The clinical diagnosis is usually obvious and laboratory diagnosis is rarely required. The clinical management is complicated by a high infectivity and a tendency to multiple recurrences.

Syphilis

Aetiology

Syphilis is now a less prevalent sexually transmitted infection in the developed world. It is caused by a spirochaete, Treponema pallidum. In the male, the primary lesion develops between 1 and 12 weeks after infection, usually on the penis at the site of inoculation. The organism probably enters the tissues through a mucosal abrasion and, by the time the primary lesion develops, the organism has already disseminated via lymphatics.

Clinicopathological features

The primary chancre usually develops on the inner aspect of the prepuce, the glans penis or corona. It forms a painless indurated nodule which soon becomes an ulcer with rounded margins. There is regional lymphadenopathy. Examination by dark-ground microscopy of the serous exudate in the base of the ulcer reveals numerous spirochaetes. Initially, the tissue response consists of oedema with necrosis and an associated exudate of fibrin and polymorphs. At a later stage there is an endarteritis with a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Thrombotic occlusion of these vessels produces necrosis and ulceration of the epidermis. There is usually an associated unilateral or bilateral inguinal lymphadenitis. Without treatment the primary chancre heals in a few weeks, leaving an atrophic scar.

The secondary and tertiary stages of syphilis develop later as a result of dissemination of the infection and are accompanied by an immunological reaction. Secondary syphilis develops within 2 years of the primary lesion and may include several different cutaneous manifestations. One of these is the development of condylomata lata on the prepuce and scrotum—proliferative epithelial lesions containing numerous spirochaetes. There is a generalised lymphadenitis in many cases.

The tertiary stage of syphilis may involve the formation of a gumma in the testis, but is also associated with thoracic aortic aneurysms and central nervous system changes.

Clinical diagnosis and management

Syphilis is diagnosed in the primary stage by microscopy of the exudate in the chancre or ulcer; the characteristic spirochaetes can be seen by dark-ground illumination. In this and later stages, the diagnosis is confirmed serologically by seeking specific antibodies in the patient’s blood; the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-Abs) test and the Treponema pallidum haemagglutination assay (TPHA) are the most specific.

Treatment is usually with penicillin, but it is essential to trace and possibly treat the patient’s sexual partners.

Lymphogranuloma venereum

Lymphogranuloma venereum is a sexually transmitted disease seen more commonly in the tropics. Infections seen in the UK, for example, have usually been acquired abroad.

Aetiology

The disease is caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis, serotypes L1–L3 (different from those associated with non-specific urethritis).

Clinicopathological features

Following a short incubation period of 2–5 days, about 50% of infected males give a history of a primary genital lesion. This lesion is a painless papule on the penis which may ulcerate but usually heals within a few days.

Between 1 and 4 weeks later the patient develops an inguinal lymphadenitis and this is the usual manifestation of the disease in the male. There is usually unilateral enlargement of the inguinal lymph nodes. The nodes are tender and initially discrete, becoming matted together as a result of pericapsular inflammation. The nodes may also become fluctuant. This lymphadenitis is often accompanied by constitutional symptoms with pyrexia and malaise. If untreated, the lymphadenitis may resolve but with some residual local lymphoedema.

The histological features are of an acute inflammation of the node with foci of necrosis surrounded by a margin of polymorphs, histiocytes and plasma cells. This inflammatory infiltrate extends through the capsule of the lymph node into the perinodal adipose tissue and may result in the development of sinuses to the overlying skin.

Clinical diagnosis

Surgical biopsy of the lymph node may be performed if the diagnosis is unsuspected; the histological features are almost pathognomonic. The diagnosis may also be made by aspirating pus from the lymph node and examining smears by specific immunofluorescence or stained by the Giemsa technique for the presence of chlamydial inclusions. A serum complement fixation test is also available.

Elephantiasis

In elephantiasis, the skin of the penis, scrotum and legs is greatly thickened by chronic oedema resulting from lymphatic obstruction. Two main groups can be distinguished:

The tropical form is relatively common in parts of Africa and other countries with a similar climate in which the causative parasite is prevalent.

Non-tropical elephantiasis

In non-tropical elephantiasis, an earlier inflammatory process such as a recurrent cellulitis results in obliteration of the lymphatics in the skin. Another cause is disruption of lymphatic flow after surgical dissection of the inguinal lymph nodes as treatment for metastatic carcinoma of the penis or scrotum.

Tropical elephantiasis

Tropical elephantiasis is a late sequel of infection by the nematode parasite Wuchereria bancrofti. The adult worm lives in the lymphatic spaces, where the female produces microfilariae which re-enter the blood. These are ingested by blood-sucking mosquitoes, developing further in the insects’ salivary glands. They re-infect humans at the time of a further bite, passing back to the lymphatics. In this site the parasite induces a granulomatous inflammation with associated fibrosis, leading to lymphatic obstruction. Mechanical blockage of the lymphatic lumen by numerous parasites contributes to the oedema.

Peyronie’s disease

Peyronie’s disease is a rare penile lesion presenting usually in the fifth and sixth decades with painful curvature of the penis on erection and, sometimes, difficulty in micturition. The lesions may gradually progress for a few years, and some later resolve spontaneously.

One or more ill-defined plaques of fibrous tissue develop along the dorsal aspect of the shaft of the penis, initially involving the corpora cavernosa. Histological examination shows fibroblast proliferation, with increasing amounts of collagen as the lesion progresses. In the early stages of Peyronie’s disease, there is also an inflammatory component with an infiltrate composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

The nature of the lesion is uncertain. Some cases are associated with palmar fibromatosis (Dupuytren’s contracture), although the inflammatory component is unlike most fibromatoses. Peyronie’s disease may be related to idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis.

Idiopathic gangrene of the scrotum (Fournier’s syndrome)

Idiopathic gangrene of the scrotum (Fournier’s syndrome) is a rare necrotising subcutaneous infection that involves the scrotum and sometimes extends to involve the penis, perineum and abdominal wall. It usually affects middle-aged to elderly men.

Aetiology

Several predisposing factors may be associated with Fournier’s syndrome: local trauma, anal fistula or ischiorectal abscess. There is an increased risk in patients with diabetes mellitus. The common aetiological factor of local tissue trauma allows bacteria to enter the subcutaneous tissue. The causative organisms are of the faecal flora, including coliforms and anaerobes such as Bacteroides, some of which are gas-forming organisms. A mixed infection is common.

Clinicopathological features

The scrotum is red and swollen with crepitus on palpation due to the presence of subcutaneous gas. This initial stage is soon followed by necrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, eventually exposing the testes. Later, the tissue slough separates, sharply demarcated from the adjacent viable skin. There is a high risk of death from multi-organ failure. Antibiotics and surgical debridement are the mainstay of treatment. Finally, if the patient survives, there is regeneration of the skin.

Thrombosis of blood vessels in the scrotal skin results in necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue and dermal gangrene.

TUMOURS OF THE PENIS

Tumours of the penis are of two types:

Intra-epidermal carcinoma

A localised area of intra-epidermal carcinoma (Bowen’s disease; see Ch. 24) may develop on the penis as on other sites on the body surface, presenting as a sharply delineated erythematous patch with a moist keratotic surface. On the glans penis this lesion is sometimes termed erythroplasia of Queyrat, with the appearance of a well-defined, slightly raised, red plaque.

The histological features are of a pre-invasive squamous cell carcinoma. The epidermis is thickened with loss of cellular polarity and stratification. There is cellular and nuclear pleomorphism with hyperchromatic nuclei and an increased number of mitoses. Many of these abnormal cells keratinise at deeper levels within the epidermis (dyskeratosis). The basal layer of the epidermis remains sharply demarcated from the dermis at this stage, although this lesion carries a significant risk of progression to invasive squamous carcinoma.

Invasive squamous carcinoma

Carcinoma of the penis is rare in the UK although common in parts of Africa, Latin America and the Far East, where it accounts for 10% of cancers in men. It occurs predominantly in uncircumcised men and is associated with phimosis, chronic balanoposthitis, balanitis xerotica obliterans and PUVA-treated psoriasis. Human papillomavirus infection (HPV 16 and 18) is an aetiological factor in a substantial proportion of cases.

The usual site at which the tumour develops is on the glans penis or inner aspect of the prepuce, forming an indurated nodule or plaque which later ulcerates. It rarely develops on the outer surface of the prepuce or on the shaft of the penis.

The tumour is usually a well-differentiated squamous carcinoma and invades the corpora cavernosa. Metastases may develop in the inguinal lymph nodes.

CARCINOMA OF THE SCROTUM

Carcinoma of the scrotum was the first recognised example of a tumour caused by occupational exposure to carcinogens. In 1775, Percival Pott recognised this association in chimney sweeps. During the sweeps’ work, soot containing carcinogens became retained in the rugose skin of the scrotum, later inducing a tumour. Since that time, other occupational factors have been identified in the development of this type of tumour, such as exposure to mineral oils. Workers handling arsenic or tar are also at risk.

Nevertheless, this tumour is now rare in the UK. It develops in elderly men, often many years after possible exposure to industrial carcinogens. It presents as a nodular, often ulcerated mass which may involve an extensive area of the scrotal skin. The tumour is a squamous carcinoma, usually well differentiated with keratinisation. The inguinal lymph nodes may be enlarged by metastatic carcinoma or as a result of reactive changes resulting from ulceration of the primary tumour.

URETHRA

URETHRAL OBSTRUCTION

The commonest cause of urethral obstruction is extrinsic compression due to prostate gland enlargement. Intrinsic lesions include:

Congenital urethral valves

Congenital urethral valves are a rare cause of urinary tract obstruction in the male neonate. In most cases this presents acutely with urinary obstruction and resulting bladder distension and muscle hypertrophy. The causative lesion is single or paired mucosal folds in the prostatic part of the urethra. Less often, a milder degree of this abnormality is first diagnosed in early adult life.

Traumatic rupture of the urethra

Traumatic rupture of the urethra is a rare event confined to males, and results from trauma such as a fall astride a hard object or complicating a fractured pelvis. The resulting damage to the wall of the urethra may involve its whole circumference or only part of it and may involve both the mucosa and muscle layers. Any part of the urethra may be involved.

The rupture leads to extravasation of urine into the periurethral tissues, which may later become the site of a secondary infection. There is difficulty in passing urine with bleeding from the urethral orifice and localised pain. A late complication of this lesion is the development of a urethral stricture.

Urethral stricture

A urethral stricture is usually an acquired lesion developing secondary to some other pathological condition of the urethra. The commonest cause is a post-inflammatory stricture following a gonococcal urethritis. This infection usually involves the peri-urethral glands and, if treatment is delayed, this condition may be associated with fibrosis around the glands and a fibrous stricture that encircles the urethra. Proximal to the stricture, the urethra becomes dilated, with hypertrophy of bladder muscle and urinary obstruction. The patient complains of difficulty in micturition with a poor stream and dribbling of urine. The retention of urine may be complicated further by the development of cystitis.

Urethral strictures may also be post-traumatic, complicating a rupture of the urethra, or develop after transurethral instrumentation or resection. A congenital stricture of the urethra occurs more rarely.

URETHRITIS

Urethritis (inflammation of the urethra) may occur in association with a more proximal infection in the urinary tract or adjacent to a local urethral lesion such as a calculus or an indwelling urinary catheter. The commonest causes, however, are the following specific primary infections of the urethra occurring as a sexually transmitted infection:

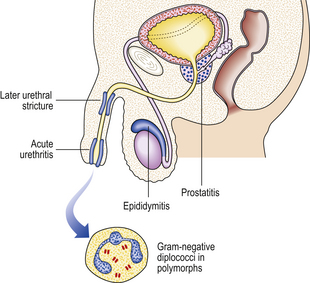

Gonococcal urethritis (gonorrhoea)

In gonococcal urethritis, the bacterial organism Neisseria gonorrhoeae (syn. gonococcus) produces an acute inflammation of the urethra. Following a short incubation period of 2–5 days after intercourse, a purulent urethral discharge develops, with pain on passing urine. If the infection spreads to the proximal urethra there may also be increased frequency of micturition. About 90% of males develop such symptoms as a result of infection, in contrast to females in whom about 70% of gonococcal infections are asymptomatic.

The gonococcus can penetrate an intact urethral mucosa, producing an infection in the submucosa that extends to the corpus spongiosum. This is an acute suppurative inflammation with increased vascularity, oedema and an infiltrate of polymorph leukocytes.

The inflammation commonly involves the peri-urethral glands and may also extend to the prostate and epididymis (Fig. 20.13). In all these sites abscesses may develop containing numerous polymorphs and bacteria with localised tissue destruction. A urethral stricture may develop many years after the initial infection as a result of fibrosis in relation to damaged peri-urethral glands. Gonorrhoea is a common infection, mainly occurring in young adults, and has a high infectivity.

Diagnosis

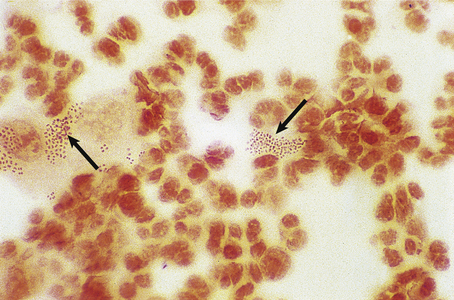

The gonococcus is a delicate organism and careful collection and transport of specimens is required for a laboratory diagnosis. A swab from the urethral mucosa may give a rapid diagnosis of gonococcal urethritis in the clinic, enabling immediate antibiotic treatment of the infection to be started. Microscopy demonstrates Gram-negative gonococci within polymorphs (Fig. 20.14).

Fig. 20.14 Gonococcal urethritis. Gram-stained pus showing numerous neutrophil polymorphs and clusters of gonococci (arrows).

Microbiological culture of the organism requires urethral swabs to be transferred promptly to the laboratory. Such a culture will provide confirmation of the diagnosis. Laboratory antibiotic sensitivity tests may also be required because of the recent emergence of strains of gonococci resistant to penicillin due to penicillinase (beta-lactamase) production.

Non-gonococcal (non-specific) urethritis

Non-gonococcal urethritis (synonymous with non-specific urethritis) is the commonest sexually transmitted disease. In males, a mucopurulent urethral discharge and dysuria develop within a few days to a few weeks of the infecting intercourse. The discharge contains pus cells but gonococci cannot be detected by microscopy or culture.

Aetiology

In about 40% of cases the cause is Chlamydia trachomatis; Ureaplasma urealyticum and Histoplasma genitalium are responsible for about a further 40%, while in the remainder no organism can yet be identified.

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular organism which structurally resembles a bacterium. Serotypes D–K are associated with genital tract infections. The infectious form of the agent, the elementary body, enters the urethral mucosal cells, enlarging to produce an initial body which is metabolically active. This body multiplies to form more organisms within a vacuole, seen on microscopy as a basophilic cytoplasmic inclusion. These organisms are released by cell rupture to infect adjacent cells.

Ureaplasma urealyticum and Histoplasma genitalium are similar Gram-negative organisms that lack a cell wall.

TUMOURS

Tumours of the urethra include:

Viral condyloma

These are analogous to the genital warts seen externally on the penis, and follow infection by human papilloma-viruses, mainly HPV 6 and 11; there is no particular risk of malignancy.

Transitional cell carcinoma

A papillary transitional cell carcinoma may rarely develop in the urethra, in association with a similar tumour in the bladder. This condition may be a separate, multifocal tumour of the urothelium, or may develop occasionally as a result of tumour implantation in the urethra following instrumentation of the bladder.

TESTIS

NORMAL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

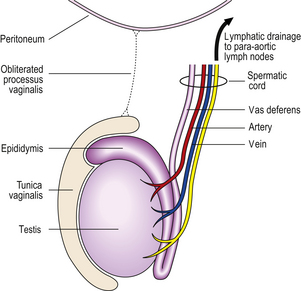

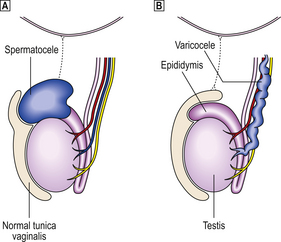

During its development, each testis descends from the posterior abdominal wall to the scrotum, carrying with it a covering layer of peritoneum which forms the tunica vaginalis, a closed serous cavity around the testis (Fig. 20.15). Blood vessels and lymphatics enter and leave the testis on its posterior surface at the hilum, which is not covered by tunica vaginalis.

Fig. 20.15 Anatomy of testis and vascular connections. Note that the lymphatic drainage of the testis is to the para-aortic lymph nodes.

Blood is supplied by the spermatic artery, a branch of the aorta, which passes along the spermatic cord. The venous return surrounds the spermatic artery as a network of intercommunicating veins, the pampiniform plexus. This plexus becomes the main testicular vein which, on the right side, drains to the inferior vena cava and, on the left, joins the left renal vein. Lymphatic drainage of the testis is to the para-aortic lymph nodes.

The testis has a fibrous capsule, the tunica albuginea. From this capsule, fibrous septa divide the testis into about 250 lobules, each containing up to four convoluted seminiferous tubules. These tubules converge on to a network of spaces, the rete testis, at the hilum, from where 10 to 12 efferent ductules lead to the epididymis. The rete testis and the efferent ductules are both lined by a ciliated epithelium.

The epididymis lies along the posterior aspect of the testis and is the main storage site for freshly formed sperm. The epididymis is a convoluted tubular structure lined by columnar epithelium.

The seminiferous tubules are each lined by a layer of germinal epithelium four or five cells thick; the more immature spermatogonia are situated close to the basement membrane. During spermatogenesis, meiotic division occurs at the spermatocyte stage; maturation of spermatids into sperm occurs near the tubular lumen. Sertoli cells lie in contact with the tubular basement membrane and insinuate between the germinal epithelial cells, providing local support and phagocytic function. In the interstitium between the seminiferous tubules, Leydig cells occur in small groups. These cells produce the hormone testosterone, which promotes spermatogenesis and the development of secondary sex characteristics, in response to stimulation by the pituitary gonadotrophic hormone, luteinising hormone.

From birth until puberty, the seminiferous tubules are small, being lined by Sertoli cells and primitive germ cells only. Spermatogenic activity starts at puberty.

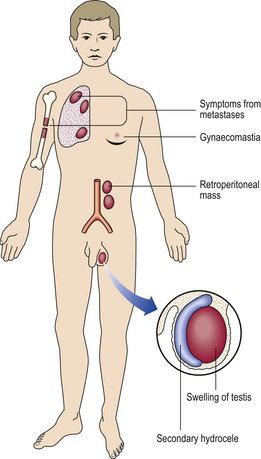

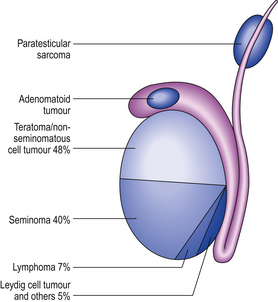

INCIDENCE OF TESTICULAR LESIONS

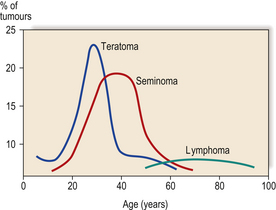

Most testicular lesions are non-neoplastic disorders (e.g. mumps orchitis, torsion), but the possibility of a tumour must be considered fully in each case of testicular swelling or pain. Many testicular lesions present with a hydrocele, an accumulation of fluid around the testis; when this has been drained the testis must be examined carefully by palpation and, if necessary, by ultrasound imaging to exclude the possibility of an underlying testicular tumour.