Anatomy

section 1 Introduction

A Osteology: The human skeleton has 206 bones: axial skeleton (80) and appendicular skeleton (126)

Intramembranous (direct laying down of bone without a cartilage model [skull]) or enchondral (with a cartilage precursor [most bones]).

Intramembranous (direct laying down of bone without a cartilage model [skull]) or enchondral (with a cartilage precursor [most bones]).

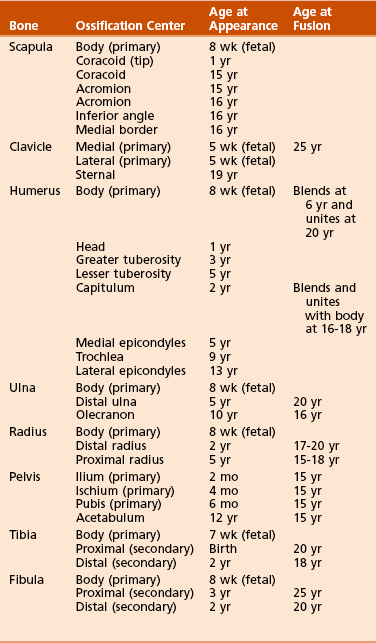

Enchondral growth begins in the diaphyses of long bones at primary ossification centers, most of which are present at birth (Table 2-1).

Enchondral growth begins in the diaphyses of long bones at primary ossification centers, most of which are present at birth (Table 2-1).

2. Secondary ossification centers usually develop in the periphery of bones and are important for growth and the treatment of childhood fractures.

3. Heterotopic ossification is the formation of bone tissue in an atypical, extraskeletal location.

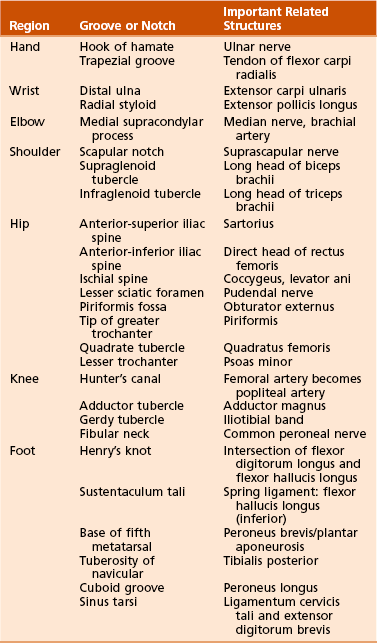

4. Anatomic landmarks of the skeleton and their related structures are listed in Table 2-2.

B Arthrology: Joints are commonly classified into three types on the basis of their freedom of movement

1. Synarthroses: joining of two bony elements with no motion during maturity; skull sutures

2. Amphiarthroses: have hyaline cartilage and intervening discs with limited motion; symphysis pubis

3. Diarthroses: characterized by hyaline cartilage, synovial membranes, capsules, and ligaments

C Myology: classification based on the arrangement of muscle fibers

2. Fusiform (e.g., biceps brachii)

3. Oblique (with tendinous interdigitation): further classified as pennate, bipennate, multipennate

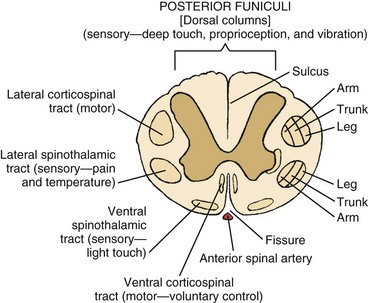

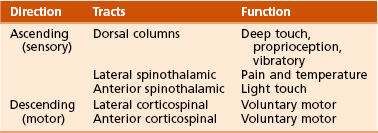

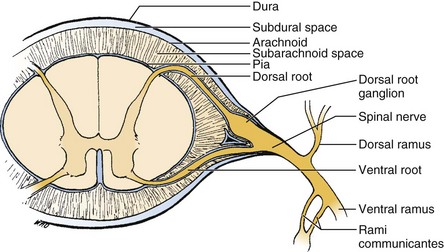

Originate from the ventral rami of spinal nerves and are distributed via several plexuses (cervical, brachial, lumbosacral)

Originate from the ventral rami of spinal nerves and are distributed via several plexuses (cervical, brachial, lumbosacral)

The mnemonic “SAME” can be used to help understand the function of nerves: sensory = afferent; motor = efferent.

The mnemonic “SAME” can be used to help understand the function of nerves: sensory = afferent; motor = efferent.

Efferent (motor) fibers carry impulses from the central nervous system to muscles.

Efferent (motor) fibers carry impulses from the central nervous system to muscles.

Afferent (sensory) fibers carry information toward the central nervous system.

Afferent (sensory) fibers carry information toward the central nervous system.

section 2 Upper Extremity

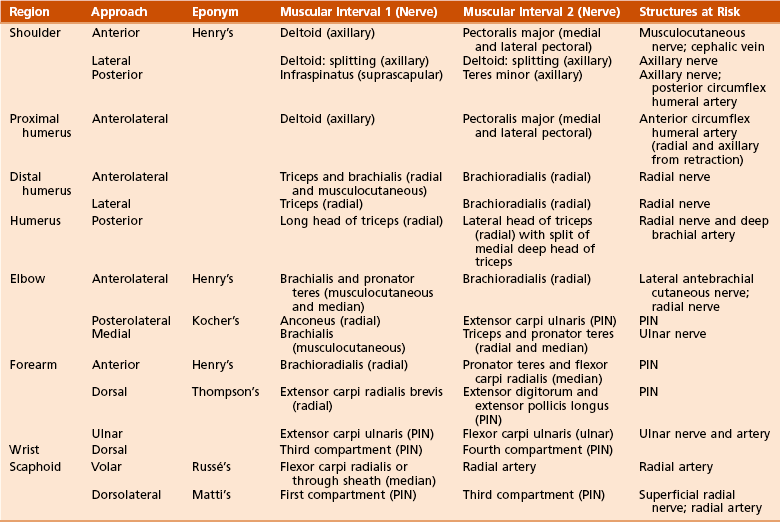

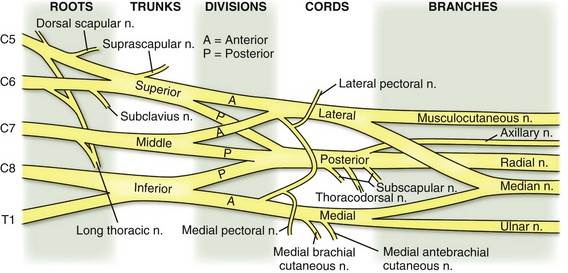

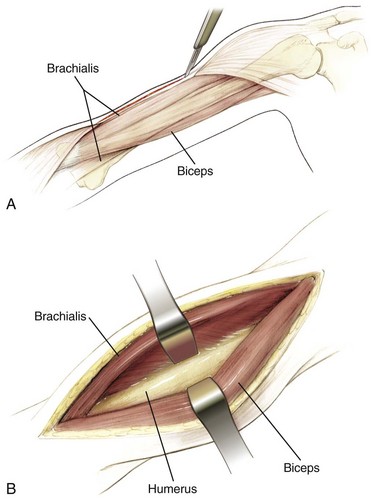

Table 2-3 summarizes upper extremity innervation. Table 2-4 summarizes standard surgical approaches to the upper extremity.

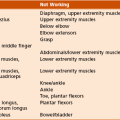

Table 2-3

Summary of Upper Extremity Innervation

| Nerves | Muscles Innervated |

| Musculocutaneous (lateral cord) | Coracobrachialis, biceps, brachialis |

| Axillary (posterior cord) | Deltoid, teres minor |

| Radial (posterior cord) | Triceps, brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis |

| Posterior interosseous | Supinator, extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus and brevis, extensor indicis proprius |

| Median (medial and lateral cord) | Pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, abductor pollicis brevis, supinator head of flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, first and second lumbrical muscles |

| Anterior interosseous | Flexor digitorum profundus (first and second), flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus |

| Ulnar (medial cord) | Flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum profundus (third and fourth), palmaris brevis, abductor digiti minimi, opponens digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi, third and fourth lumbrical muscles, interossei, adductor pollicis, deep head of flexor pollicis brevis |

Spans the second through seventh ribs and serves as an attachment for 17 muscles and four ligaments

Spans the second through seventh ribs and serves as an attachment for 17 muscles and four ligaments

Glenoid is retroverted approximately 5 degrees.

Glenoid is retroverted approximately 5 degrees.

Scapular spine: separates supraspinatus from infraspinatus.

Scapular spine: separates supraspinatus from infraspinatus.

Coracoid: Attachments to the coracoid include the coracoacromial ligament, coracoclavicular ligaments (conoid and trapezoid [lateral]), conjoined tendon (coracobrachialis and short head of biceps), and pectoralis minor.

Coracoid: Attachments to the coracoid include the coracoacromial ligament, coracoclavicular ligaments (conoid and trapezoid [lateral]), conjoined tendon (coracobrachialis and short head of biceps), and pectoralis minor.

Suprascapular notch has the superior transverse scapular ligament separating the suprascapular artery (superior) from the suprascapular nerve (inferior).

Suprascapular notch has the superior transverse scapular ligament separating the suprascapular artery (superior) from the suprascapular nerve (inferior).

Spinoglenoid notch has both the artery and nerve inferior to the inferior transverse scapular ligament; long-term nerve compression at the spinoglenoid notch (i.e., ganglion; assume labral disease) results in infraspinatus atrophy.

Spinoglenoid notch has both the artery and nerve inferior to the inferior transverse scapular ligament; long-term nerve compression at the spinoglenoid notch (i.e., ganglion; assume labral disease) results in infraspinatus atrophy.

It is the fulcrum for lateral movement of the arm.

It is the fulcrum for lateral movement of the arm.

It has a double curvature (sternal-ventral, acromial-dorsal) and serves as an attachment for the upper extremity.

It has a double curvature (sternal-ventral, acromial-dorsal) and serves as an attachment for the upper extremity.

The clavicle is the first bone in the body to ossify (at 5 weeks of gestation) and the last to fuse (medial epiphysis at 25 years of age; see Table 2-1). Fracture of the clavicle is the most common musculoskeletal birth injury.

The clavicle is the first bone in the body to ossify (at 5 weeks of gestation) and the last to fuse (medial epiphysis at 25 years of age; see Table 2-1). Fracture of the clavicle is the most common musculoskeletal birth injury.

B Arthrology: one major articulation (glenohumeral joint) and several minor articulations (sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, scapulothoracic joints)

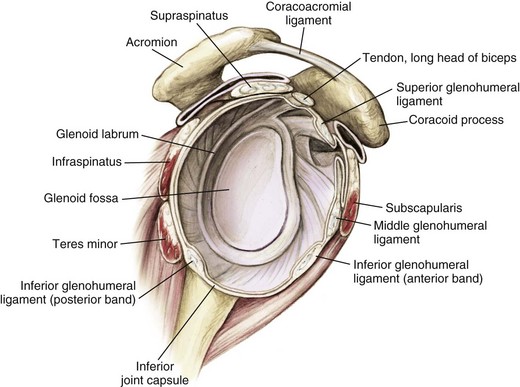

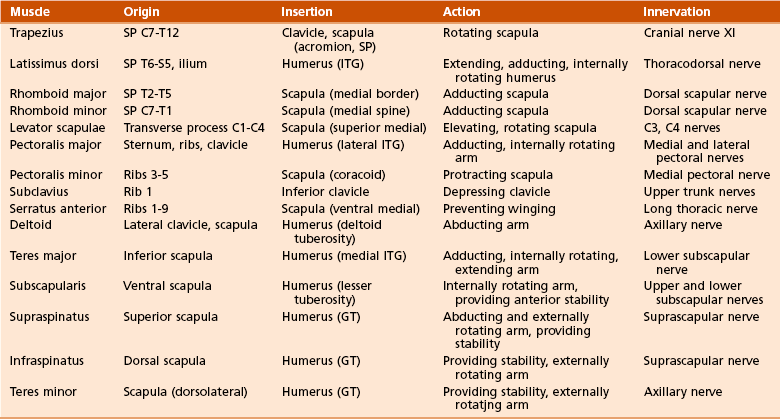

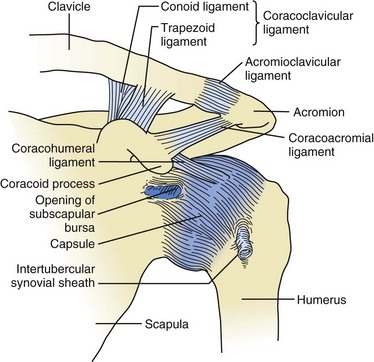

1. Glenohumeral joint (Figure 2-1): Spheroidal, ball and socket, with the greatest joint range of motion; motion is at the expense of stability with static and dynamic restraints.

Static restraints include the articular anatomy, glenoid labrum, negative pressure, capsule, and ligaments.

Static restraints include the articular anatomy, glenoid labrum, negative pressure, capsule, and ligaments.

Dynamic restraints include the rotator cuff and biceps tendon, and scapulothoracic motion is restrained.

Dynamic restraints include the rotator cuff and biceps tendon, and scapulothoracic motion is restrained.

Important glenohumeral stabilizers summarized in Table 2-5

Important glenohumeral stabilizers summarized in Table 2-5

Table 2-5

| Structure | Function |

| Coracohumeral ligament | Primary restraint in inferior translation of the adducted arm and to external rotation |

| Glenoid labrum | Increases surface area, static stabilizer |

| Superior glenohumeral ligament | Primary restraint in external rotation of the adducted or slightly abducted arm Primary restraint in inferior translation of the adducted arm |

| Middle glenohumeral ligament (absent up to 30% of shoulders) | Primary stabilizer in anterior translation, with the arm abducted to 45 degrees |

| Inferior glenohumeral ligament complex | Primary stabilizer for anterior and inferior translation in abduction |

This joint is double-gliding, with an articular disc.

This joint is double-gliding, with an articular disc.

Ligaments include the anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments, an interclavicular ligament, and a costoclavicular ligament.

Ligaments include the anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments, an interclavicular ligament, and a costoclavicular ligament.

The sternoclavicular joint rotates 30 degrees with shoulder motion.

The sternoclavicular joint rotates 30 degrees with shoulder motion.

Plane/gliding joint with a fibrocartilaginous disc

Plane/gliding joint with a fibrocartilaginous disc

Figure 2-2 Ligaments about the shoulder. The acromioclavicular ligaments (superior, inferior, anterior, and posterior) prevent anteroposterior translation of the distal clavicle. The superior ligament is the most important and is reinforced by fibers from the trapezius and deltoid muscles. The coracoclavicular ligaments—conoid (posteromedial) and trapezoid (anterolateral)—prevent superior translation of the distal clavicle. The coracoacromial ligament should be preserved in massive rotator cuff defects because it provides superior restraint to the humeral head. Bleeding encountered during release of the coracoacromial ligament comes from the acromial branch of the thoracoacromial artery (second part of axillary artery; see Figure 2-6). (Adapted from Jenkins DB: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 6, Philadelphia, 1991, Saunders, p 71.)

Acromioclavicular ligament: prevents anteroposterior displacement

Acromioclavicular ligament: prevents anteroposterior displacement

Coracoclavicular ligaments: prevent superior displacement of the distal clavicle (trapezoid [anterolateral] and conoid [posteromedial and stronger])

Coracoclavicular ligaments: prevent superior displacement of the distal clavicle (trapezoid [anterolateral] and conoid [posteromedial and stronger])

When the arm is maximally elevated, about 5 to 8 degrees of rotation is possible at the acromioclavicular joint, although the clavicle rotates approximately 40 to 50 degrees.

When the arm is maximally elevated, about 5 to 8 degrees of rotation is possible at the acromioclavicular joint, although the clavicle rotates approximately 40 to 50 degrees.

Though not a true joint, this attachment allows scapular movement against the posterior rib cage.

Though not a true joint, this attachment allows scapular movement against the posterior rib cage.

Fixed primarily by the scapular muscular attachments.

Fixed primarily by the scapular muscular attachments.

Glenohumeral motion in comparison with scapulothoracic motion is in a 2:1 ratio.

Glenohumeral motion in comparison with scapulothoracic motion is in a 2:1 ratio.

5. Intrinsic ligaments of the scapula:

Superior transverse scapular ligament (which separates the suprascapular nerve [inferior] and vessels [superior] at the suprascapular notch; mnemonic: “Army over Navy” for artery over nerve)

Superior transverse scapular ligament (which separates the suprascapular nerve [inferior] and vessels [superior] at the suprascapular notch; mnemonic: “Army over Navy” for artery over nerve)

Inferior transverse scapular ligament (spinoglenoid notch)

Inferior transverse scapular ligament (spinoglenoid notch)

Frequent cause of impingement.

Frequent cause of impingement.

The coracoacromial ligament is important for superoanterior restraint in rotator cuff deficiencies and should be preserved during débridement of painful massive rotator cuff tears that cannot be surgically repaired.

The coracoacromial ligament is important for superoanterior restraint in rotator cuff deficiencies and should be preserved during débridement of painful massive rotator cuff tears that cannot be surgically repaired.

The acromial branch of the thoracoacromial artery runs on the medial aspect of the coracoacromial ligament.

The acromial branch of the thoracoacromial artery runs on the medial aspect of the coracoacromial ligament.

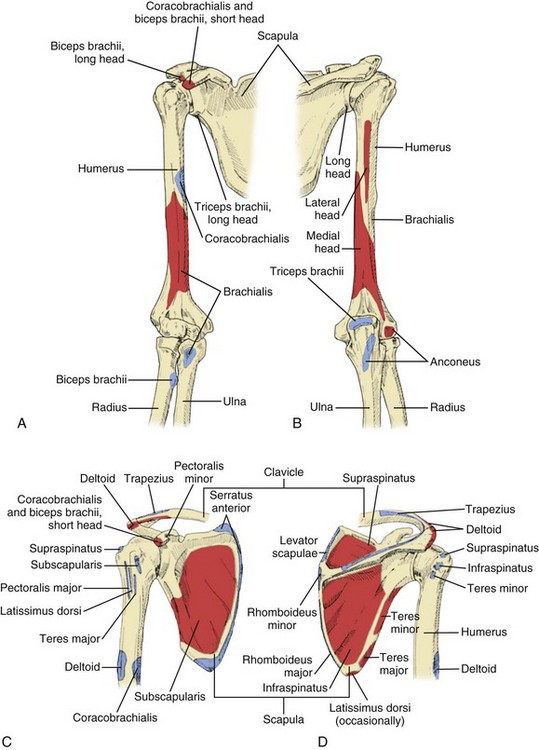

1. Muscles connecting the upper limb to the vertebral column: trapezius, latissimus, both rhomboid muscles, and levator scapulae

2. Muscles connecting the upper limb to the thoracic wall: both pectoralis muscles, subclavius, and serratus anterior

3. Muscles acting on the shoulder joint itself: deltoid, teres major, and the four rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis)

The rotator cuff muscles depress and stabilize the humeral head against the glenoid; all attach to the greater tuberosity except the subscapularis, which has a lesser tuberosity insertion (shoulder internal rotator).

The rotator cuff muscles depress and stabilize the humeral head against the glenoid; all attach to the greater tuberosity except the subscapularis, which has a lesser tuberosity insertion (shoulder internal rotator).

The shoulder internal rotators (pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and subscapularis) are stronger than the external rotators (teres minor and infraspinatus), which is why posterior shoulder dislocations are more common than anterior dislocations after electrical shock and seizures.

The shoulder internal rotators (pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and subscapularis) are stronger than the external rotators (teres minor and infraspinatus), which is why posterior shoulder dislocations are more common than anterior dislocations after electrical shock and seizures.

Table 2-6 presents the specific characteristics of these muscles, and Figure 2-4 and Table 2-7 describe the four layers of shoulder musculature.

Table 2-6 presents the specific characteristics of these muscles, and Figure 2-4 and Table 2-7 describe the four layers of shoulder musculature.

Table 2-7

Shoulder-Supporting Anatomic Layers

| Layer | Structures |

| I | Deltoid; pectoralis major; trapezius |

| II | Clavipectoral fascia; conjoined tendon, short head of biceps, and coracobrachialis |

| III | Deep layer of subdeltoid bursa; rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis [SITS]) |

| IV | Glenohumeral joint capsule; coracohumeral ligament |

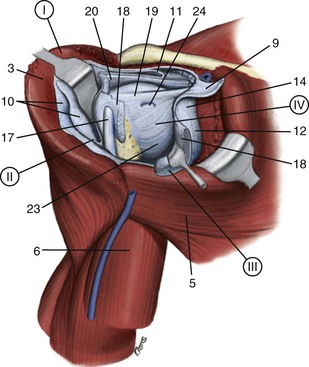

1. Anatomy of brachial plexus (Figure 2-5)

The brachial plexus is formed from the ventral primary rami of C5 to T1 and lies under the clavicle between the scalenus anterior and scalenus medius.

The brachial plexus is formed from the ventral primary rami of C5 to T1 and lies under the clavicle between the scalenus anterior and scalenus medius.

Dorsal rami of C5 to T1 innervate the dorsal neck musculature and skin.

Dorsal rami of C5 to T1 innervate the dorsal neck musculature and skin.

Brachial plexus consists of roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches (mnemonic: “Ron Taylor drinks cold beer”).

Brachial plexus consists of roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches (mnemonic: “Ron Taylor drinks cold beer”).

Five roots (C5 to T1, although contributions from C4 and T2 can be small)

Five roots (C5 to T1, although contributions from C4 and T2 can be small)

Three trunks (upper, middle, lower)

Three trunks (upper, middle, lower)

Six divisions (two from each trunk)

Six divisions (two from each trunk)

Three cords (named because of their anatomic relationship to the axillary artery: posterior, lateral, and medial); the termination of each cord is shown in Table 2-8

Three cords (named because of their anatomic relationship to the axillary artery: posterior, lateral, and medial); the termination of each cord is shown in Table 2-8

Table 2-8

Brachial Plexus Cord Terminations

| Cord | Termination |

| Lateral | Musculocutaneous nerve* Lateral pectoral nerve |

| Posterior | Radial and axillary nerve* Upper and lower subscapular nerve Thoracodorsal nerve |

| Medial | Ulnar nerve* Medial pectoral nerve Medial brachial cutaneous nerve Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve |

| Medial and lateral | Median nerve* |

Multiple branches: four preclavicular branches (from roots and upper trunk):

Multiple branches: four preclavicular branches (from roots and upper trunk):

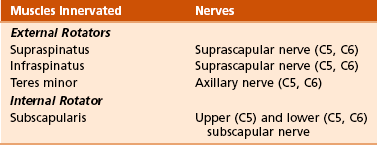

2. Muscle innervation: innervation of all rotator cuff muscles derived from C5 and C6 of the brachial plexus (Table 2-9; see also Table 2-3)

Preganglionic brachial plexus lesions

Preganglionic brachial plexus lesions

Proximal to the dorsal root ganglion

Proximal to the dorsal root ganglion

Produce medial scapular winging (because of paralysis of the preclavicular long thoracic nerve with resultant serratus anterior dysfunction) and Horner’s syndrome (injury to brachial plexus at C8 to T1 involving the inferior/stellate ganglion)

Produce medial scapular winging (because of paralysis of the preclavicular long thoracic nerve with resultant serratus anterior dysfunction) and Horner’s syndrome (injury to brachial plexus at C8 to T1 involving the inferior/stellate ganglion)

Postganglionic brachial plexus injuries

Postganglionic brachial plexus injuries

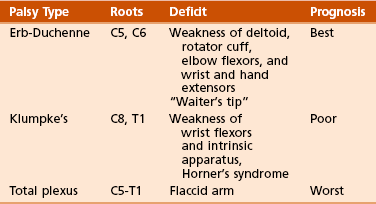

Obstetric brachial plexus palsy (Table 2-10)

Obstetric brachial plexus palsy (Table 2-10)

The left subclavian artery arises directly from the aorta, and the right subclavian artery arises from the brachiocephalic trunk.

The left subclavian artery arises directly from the aorta, and the right subclavian artery arises from the brachiocephalic trunk.

It then emerges between the scalenus anterior and medius muscles and becomes the axillary artery at the outer border of the first rib.

It then emerges between the scalenus anterior and medius muscles and becomes the axillary artery at the outer border of the first rib.

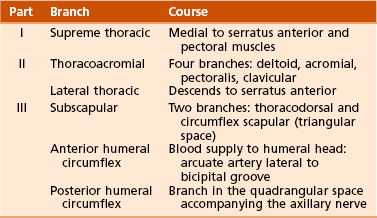

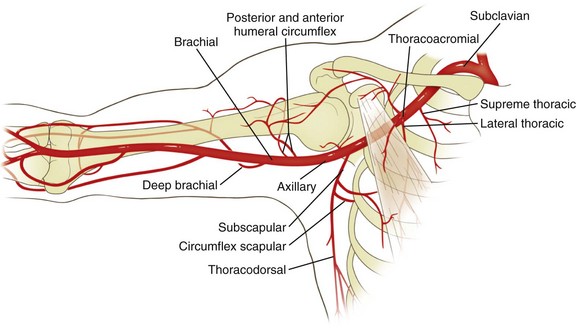

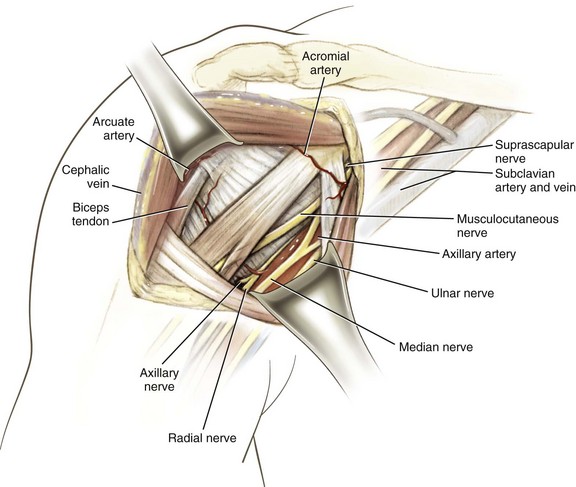

2. Axillary artery (Table 2-11, Figure 2-6)

This artery is conceptualized as divided into three parts on the basis of its physical relationship to the pectoralis minor muscle (the first part is medial to it, the second is under it, and the third is lateral to it).

This artery is conceptualized as divided into three parts on the basis of its physical relationship to the pectoralis minor muscle (the first part is medial to it, the second is under it, and the third is lateral to it).

Each part of the artery has as many branches as the number of that portion (e.g., the second part has two branches: thoracoacromial and lateral thoracic).

Each part of the artery has as many branches as the number of that portion (e.g., the second part has two branches: thoracoacromial and lateral thoracic).

The third part of the axillary artery, at the origin of the anterior and posterior humeral circumflex arteries, is the most vulnerable to traumatic vascular injury.

The third part of the axillary artery, at the origin of the anterior and posterior humeral circumflex arteries, is the most vulnerable to traumatic vascular injury.

F Surgical approaches to the shoulder (Table 2-12; see Table 2-4):

Table 2-12

Surgical Approaches to the Shoulder

| Approach | Interval | Structures at Risk |

| Anterior (Henry’s) | Deltoid (axillary nerve) and pectoralis major (medial and lateral pectoral nerve) | Axillary nerve limits inferior exposure; place arm in adduction and external rotation Musculocutaneous nerve: avoid vigorous retraction and medial dissection to the conjoined tendon/coracobrachialis |

| Lateral | Deltoid splitting (axillary nerve) | Avoid deltoid split >5 cm below acromion, to avoid damaging axillary nerve |

| Posterior | Infraspinatus (suprascapular nerve) and teres minor (axillary nerve) | Dissection inferior to the teres minor puts quadrangular space structures at risk: axillary nerve and posterior humeral circumflex artery Avoid excessive medial retraction on infraspinatus, which can injure suprascapular nerve |

1. Anterior (Henry’s) approach (Figure 2-7)

Interval: deltoid (axillary nerve) and the pectoralis major (medial and lateral pectoral nerves)

Interval: deltoid (axillary nerve) and the pectoralis major (medial and lateral pectoral nerves)

Dissect the cephalic vein, and retract it laterally with the deltoid, thereby exposing the underlying subscapularis.

Dissect the cephalic vein, and retract it laterally with the deltoid, thereby exposing the underlying subscapularis.

Then divide the subscapularis (preserving the most inferior fibers in order to protect the axillary nerve); then the shoulder capsule is visualized.

Then divide the subscapularis (preserving the most inferior fibers in order to protect the axillary nerve); then the shoulder capsule is visualized.

A leash of three vessels (one artery and the superior and inferior venae comitantes) marks the lower border of the subscapularis.

A leash of three vessels (one artery and the superior and inferior venae comitantes) marks the lower border of the subscapularis.

Musculocutaneous nerve (lateral cord brachial plexus)

Musculocutaneous nerve (lateral cord brachial plexus)

Protect by avoiding vigorous retraction of the conjoined tendon and avoiding dissection medial to the coracobrachialis.

Protect by avoiding vigorous retraction of the conjoined tendon and avoiding dissection medial to the coracobrachialis.

This nerve usually penetrates the biceps/coracobrachialis 5 to 8 cm below the coracoid, but it enters these muscles proximal to this 5-cm “safe zone” in almost 30% of shoulders.

This nerve usually penetrates the biceps/coracobrachialis 5 to 8 cm below the coracoid, but it enters these muscles proximal to this 5-cm “safe zone” in almost 30% of shoulders.

Palsy of the musculocutaneous nerve would affect the coracobrachialis, biceps brachii, and brachialis muscles, and it would affect sensation in the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve (termination of the musculocutaneous nerve).

Palsy of the musculocutaneous nerve would affect the coracobrachialis, biceps brachii, and brachialis muscles, and it would affect sensation in the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve (termination of the musculocutaneous nerve).

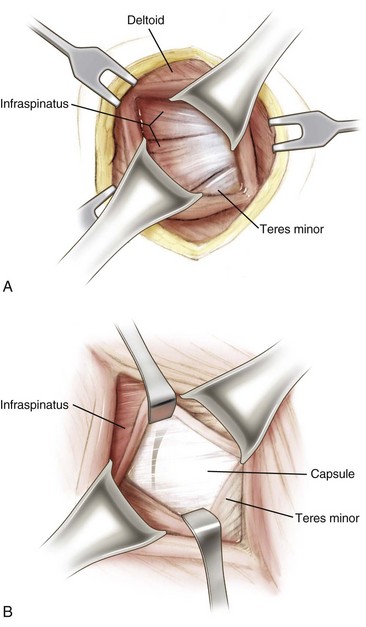

3. Posterior approach (Figure 2-8)

Interval: infraspinatus (suprascapular nerve) and teres minor (axillary nerve)

Interval: infraspinatus (suprascapular nerve) and teres minor (axillary nerve)

Dissection: Split the posterior deltoid, thereby exposing the interval between the infraspinatus and teres minor; the posterior capsule lies immediately beneath it.

Dissection: Split the posterior deltoid, thereby exposing the interval between the infraspinatus and teres minor; the posterior capsule lies immediately beneath it.

Risks: Both the axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery run in the quadrangular space below the teres minor, so it is important to stay above this muscle. Excessive medial retraction of the infraspinatus can injure the suprascapular nerve.

Risks: Both the axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery run in the quadrangular space below the teres minor, so it is important to stay above this muscle. Excessive medial retraction of the infraspinatus can injure the suprascapular nerve.

G Arthroscopy (discussed in Chapter 4, Sports Medicine)

Articulates with the smaller scapular glenoid cavity

Articulates with the smaller scapular glenoid cavity

Retroverted 30 degrees (in relation to the transepicondylar axis of the humerus)

Retroverted 30 degrees (in relation to the transepicondylar axis of the humerus)

2. Anatomic neck, directly below the humeral head, serves as an attachment for the shoulder capsule.

3. Surgical neck is lower and is more often involved in fractures.

4. Greater tuberosity is lateral to the humeral head.

Serves as the attachment for the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles (anterior to posterior, respectively)

Serves as the attachment for the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles (anterior to posterior, respectively)

5. Lesser tuberosity, located anteriorly, has only one muscular insertion: the last rotator cuff muscle, the subscapularis.

6. Bicipital groove (for the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii) is a bony groove between the two tuberosities.

7. Humeral shaft has a posterior spiral groove (for the radial nerve) adjacent to the deltoid tuberosity and approximately 13 cm above the articular surface of the trochlea.

8. Distally, the humerus flares into medial and lateral epicondyles.

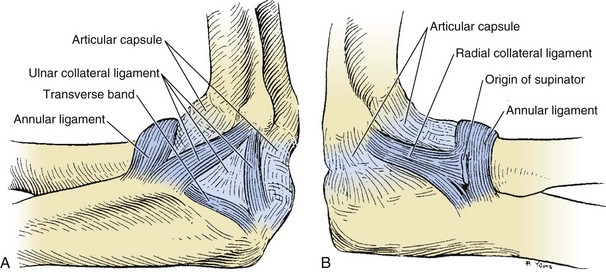

Elbow is composed of a hinge joint (the humeroulnar articulation) and a pivot joint (the humeroradial articulation) (Table 2-13).

Elbow is composed of a hinge joint (the humeroulnar articulation) and a pivot joint (the humeroradial articulation) (Table 2-13).

Table 2-13

| Articulation | Components |

| Humeroulnar | Trochlea and trochlear notch |

| Humeroradial | Capitulum and radial head |

| Proximal radioulnar | Radial notch and radial head |

Axis of rotation for the elbow is centered through the trochlea and capitellum and passes through a point anteroinferior on the medial epicondyle.

Axis of rotation for the elbow is centered through the trochlea and capitellum and passes through a point anteroinferior on the medial epicondyle.

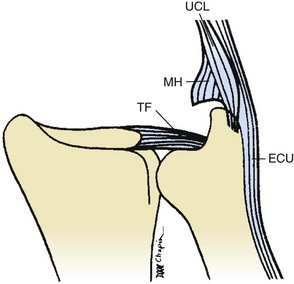

Elbow joint has capsuloligamentous tissues (Figure 2-9) that are a key source of testable material.

Elbow joint has capsuloligamentous tissues (Figure 2-9) that are a key source of testable material.

Table 2-14![]()

| Ligament | Components | Comments |

| Medial collateral | Anterior bundle of MCL (ulnar collateral); posterior bundle; transverse bundle (Cooper ligament) | Anterior bundle (strongest of all elbow ligaments): anterior band taut from 60 degrees of flexion to full extension, posterior band taut from 60-120 degrees of flexion |

| Lateral collateral | LUCL; annular ligament; quadrate (annular ligament to radial neck) and oblique cord | Deficiency of LUCL results in posterolateral rotator instability |

LUCL, lateral ulnar collateral ligament; MCL, medial collateral ligament.

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) (anterior, posterior, and transverse bundles) arises from the anteroinferior portion of the medial humeral epicondyle and provides stability in valgus stress.

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) (anterior, posterior, and transverse bundles) arises from the anteroinferior portion of the medial humeral epicondyle and provides stability in valgus stress.

The anterior bundle is the most important in helping resist valgus forces and attaches 18 mm distal to the coronoid tip.

The anterior bundle is the most important in helping resist valgus forces and attaches 18 mm distal to the coronoid tip.

Valgus stability with the arm in pronation suggests that the anterior bundle of the MCL is intact.

Valgus stability with the arm in pronation suggests that the anterior bundle of the MCL is intact.

The lateral or radial collateral ligament (annular, radial, and ulnar parts) originates on the lateral humeral epicondyle near the axis of elbow rotation.

The lateral or radial collateral ligament (annular, radial, and ulnar parts) originates on the lateral humeral epicondyle near the axis of elbow rotation.

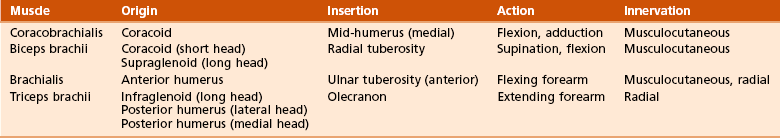

C Muscles: four muscles of the arm controlling elbow motion (Table 2-15)

1. Flexors (biceps, brachialis, and brachioradialis); the brachialis attaches to the coronoid at 11 mm distal to the tip

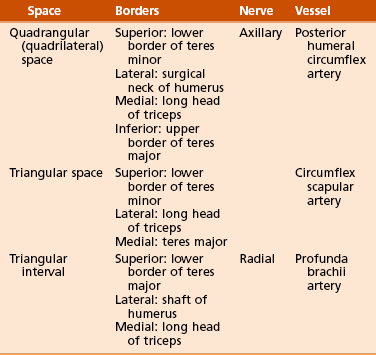

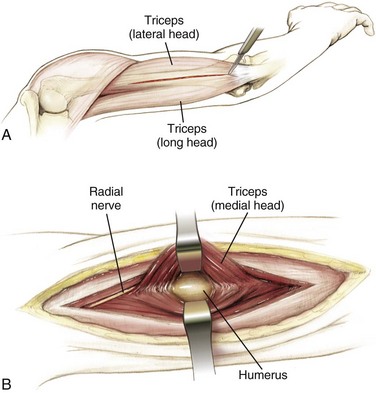

2. Extensors (triceps); also helps form borders for three important spaces (Figure 2-10 and Table 2-16)

Triangular space: bordered by teres minor (superiorly), teres major (inferiorly), and long head of biceps brachii (laterally)

Triangular space: bordered by teres minor (superiorly), teres major (inferiorly), and long head of biceps brachii (laterally)

Quadrangular space: bordered by the teres minor (superiorly) and teres major (inferiorly); medial border formed by the long head of the triceps, and lateral border formed by the humerus

Quadrangular space: bordered by the teres minor (superiorly) and teres major (inferiorly); medial border formed by the long head of the triceps, and lateral border formed by the humerus

Triangular interval: immediately inferior to the quadrangular space and bordered by the teres major (superiorly), long head of the triceps (medially), and lateral head of the triceps or the humerus (laterally)

Triangular interval: immediately inferior to the quadrangular space and bordered by the teres major (superiorly), long head of the triceps (medially), and lateral head of the triceps or the humerus (laterally)

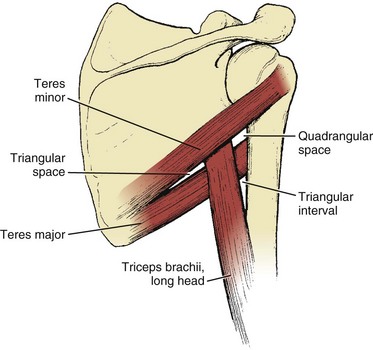

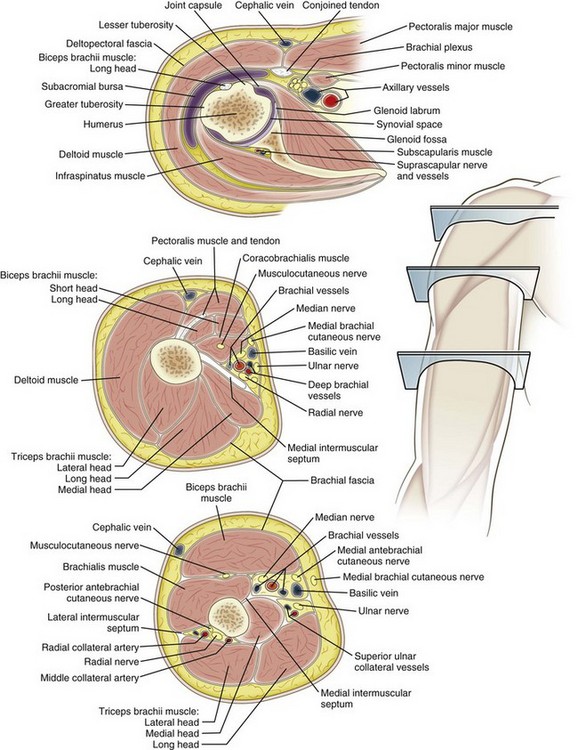

Four major nerves traverse the arm; two give off branches to arm musculature, and two innervate the distal musculature (Figure 2-11). Most of the cutaneous innervation of the arm arises directly from the brachial plexus.

Four major nerves traverse the arm; two give off branches to arm musculature, and two innervate the distal musculature (Figure 2-11). Most of the cutaneous innervation of the arm arises directly from the brachial plexus.

Musculocutaneous nerve (lateral cord):

Musculocutaneous nerve (lateral cord):

Pierces the coracobrachialis 5 to 8 cm distal to the coracoid

Pierces the coracobrachialis 5 to 8 cm distal to the coracoid

Branches to supply the coracobrachialis, the biceps, and the brachialis

Branches to supply the coracobrachialis, the biceps, and the brachialis

Gives off a branch to the elbow joint before it becomes the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve of the forearm, which is located deep to the cephalic vein

Gives off a branch to the elbow joint before it becomes the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve of the forearm, which is located deep to the cephalic vein

Radial nerve (posterior cord):

Radial nerve (posterior cord):

Spirals around the humerus (medial to lateral) in the spiral groove at a distance of approximately 13 cm from the trochlea

Spirals around the humerus (medial to lateral) in the spiral groove at a distance of approximately 13 cm from the trochlea

Emerges on the lateral side of the arm after piercing the lateral intermuscular septum approximately 7.5 cm above the trochlea between the brachialis and brachioradialis anterior to the lateral epicondyle (where it supplies the anconeus muscle)

Emerges on the lateral side of the arm after piercing the lateral intermuscular septum approximately 7.5 cm above the trochlea between the brachialis and brachioradialis anterior to the lateral epicondyle (where it supplies the anconeus muscle)

Median nerve (medial and lateral cords):

Median nerve (medial and lateral cords):

Accompanies the brachial artery along the arm, crossing it during its course (lateral to medial)

Accompanies the brachial artery along the arm, crossing it during its course (lateral to medial)

Supplies some branches to the elbow joint but has no branches in the arm itself

Supplies some branches to the elbow joint but has no branches in the arm itself

Passes medial to the brachial artery in the arm and then runs behind the medial epicondyle of the humerus, where it is superficial

Passes medial to the brachial artery in the arm and then runs behind the medial epicondyle of the humerus, where it is superficial

Supraclavicular nerve (C3 and C4) supplies the upper shoulder.

Supraclavicular nerve (C3 and C4) supplies the upper shoulder.

Axillary nerve supplies the shoulder joint and the overlying skin.

Axillary nerve supplies the shoulder joint and the overlying skin.

Medial, lateral, and dorsal brachial cutaneous nerves supply the balance of the cutaneous innervation of the arm.

Medial, lateral, and dorsal brachial cutaneous nerves supply the balance of the cutaneous innervation of the arm.

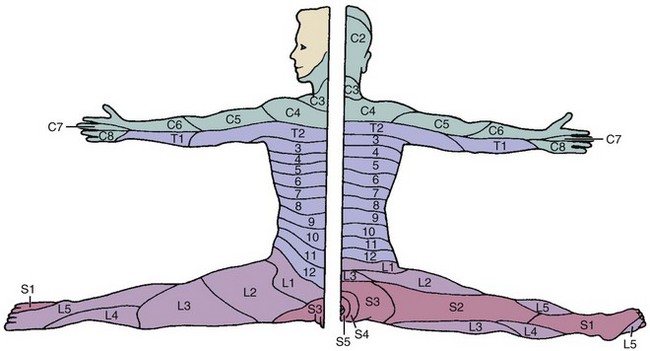

Lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve is the termination of the musculocutaneous nerve (Figure 2-12 summarizes the dermatome patterns).

Lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve is the termination of the musculocutaneous nerve (Figure 2-12 summarizes the dermatome patterns).

Figure 2-12![]() Dermatome patterns.

Dermatome patterns.

2. Compressive neuropathies (Table 2-17)

Table 2-17

Nerve Compression Syndromes of the Arm and Forearm

| Syndrome | Nerve Involved | Sites of Compression |

| Pronator | Median | Supracondylar process of humerus and ligament of Struthers Lacertus fibrosis (bicipital aponeurosis) Pronator teres Arch of flexor digitorum superficialis |

| AIN | AIN of median | Deep head of pronator teres Flexor digitorum superficialis Aberrant vessels Accessory muscles (i.e., Gantzer’s muscles) |

| Cubital tunnel | Ulnar | Arcade of Struthers Medial intermuscular septum Medial epicondyle Cubital tunnel Proximal edge of flexor carpi ulnaris (Osborne fascia) Deep flexor pronator aponeurosis |

| PIN Radial tunnel |

PIN of radial | Fibrous bands Recurrent leash of Henry Extensor carpi radialis brevis Arcade of Frohse (proximal edge of superficial head of supinator) Supinator distal margin |

| Superficial radial nerve | Superficial radial | Between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus |

AIN, anterior interosseous nerve; PIN, posterior interosseous nerve.

Originates at the lower border of the tendon of the teres major and continues to the elbow, where it bifurcates into the radial and ulnar arteries (see Figure 2-11)

Originates at the lower border of the tendon of the teres major and continues to the elbow, where it bifurcates into the radial and ulnar arteries (see Figure 2-11)

Lies medial in the arm, curving laterally to enter the cubital fossa

Lies medial in the arm, curving laterally to enter the cubital fossa

Cubital fossa: formed by the distal humerus proximally, the brachioradialis laterally, and the pronator teres medially

Cubital fossa: formed by the distal humerus proximally, the brachioradialis laterally, and the pronator teres medially

Deep brachial (also known as the profunda, this artery accompanies the radial nerve posteriorly in the triangular interval)

Deep brachial (also known as the profunda, this artery accompanies the radial nerve posteriorly in the triangular interval)

Superior and inferior ulnar collateral arteries

Superior and inferior ulnar collateral arteries

The nutrient and muscular branches

The nutrient and muscular branches

The supratrochlear artery (the least flexible branch)

The supratrochlear artery (the least flexible branch)

These collateral vessels can bind up the brachial artery with distal humerus fractures

These collateral vessels can bind up the brachial artery with distal humerus fractures

F Surgical approaches to the humerus. (Table 2-18)

Table 2-18

Surgical Approaches to the Humerus

| Approach | Interval | Structures at Risk |

| Anterolateral—proximal | Proximal—deltoid (axillary nerve) and pectoralis major (medial and lateral pectoral nerve) Distal—brachialis (radial and musculocutaneous nerve) |

Radial nerve; axillary nerve; anterior humeral circumflex artery |

| Posterior | Triceps (radial nerve); lateral and long heads | Radial nerve; deep brachial artery |

| Anterolateral—distal | Brachialis (musculocutaneous and radial nerve) and brachioradialis (radial nerve) | Radial nerve |

| Lateral | Triceps (radial nerve) and brachioradialis (radial nerve) | Radial nerve with proximal extension |

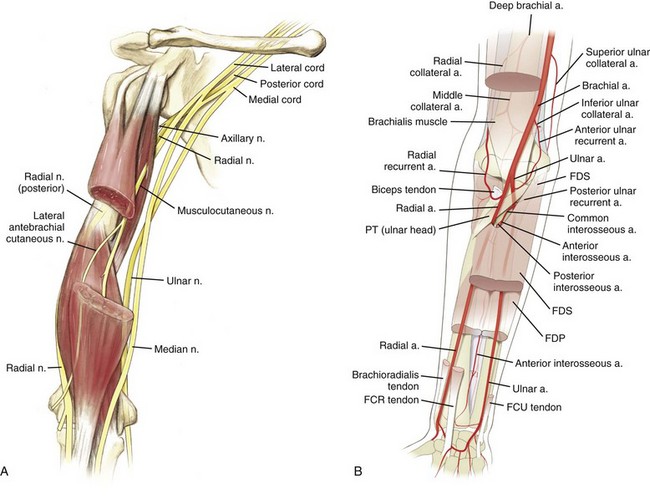

1. Anterolateral approach to the humerus (Figure 2-13)

Interval: deltoid (axillary nerve) and pectoralis major (medial and lateral pectoral nerves) proximally and between the fibers of the brachialis (radial and musculocutaneous nerves) distally

Interval: deltoid (axillary nerve) and pectoralis major (medial and lateral pectoral nerves) proximally and between the fibers of the brachialis (radial and musculocutaneous nerves) distally

Proximal approach: the anterior circumflex humeral vessels may need to be ligated

Proximal approach: the anterior circumflex humeral vessels may need to be ligated

Distal approach: between the biceps and brachialis laterally, or the brachialis can be split because of its dual innervation

Distal approach: between the biceps and brachialis laterally, or the brachialis can be split because of its dual innervation

Risks: The radial and axillary nerves are at risk for injury mainly because of forceful retraction.

Risks: The radial and axillary nerves are at risk for injury mainly because of forceful retraction.

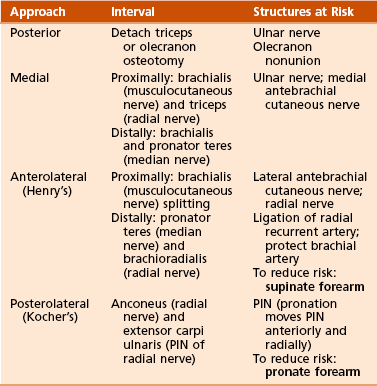

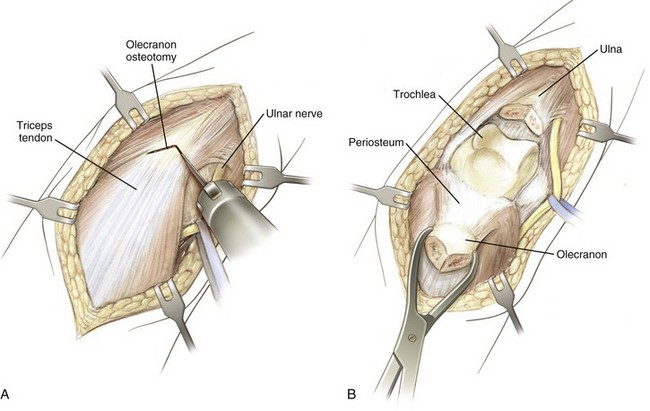

G Surgical approaches to the elbow (Table 2-19)

1. Posterior approach to the elbow (Figure 2-15)

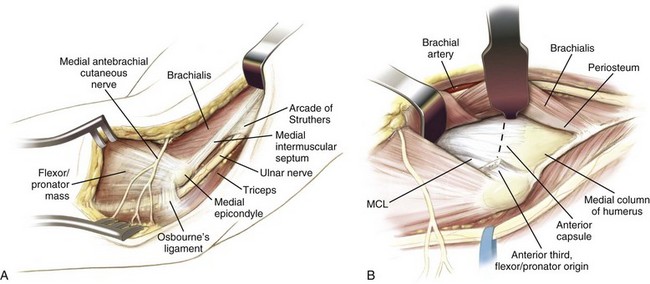

2. Medial approach to the elbow (Figure 2-16)

Interval: between the brachialis (musculocutaneous nerve) and the triceps (radial nerve) proximally and between the brachialis and pronator teres (median nerve) distally.

Interval: between the brachialis (musculocutaneous nerve) and the triceps (radial nerve) proximally and between the brachialis and pronator teres (median nerve) distally.

Dissection: Incise the anterior third of the flexor pronator mass to reach the anterior elbow capsule.

Dissection: Incise the anterior third of the flexor pronator mass to reach the anterior elbow capsule.

Risks: The ulnar and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves are in the field and must be protected.

Risks: The ulnar and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves are in the field and must be protected.

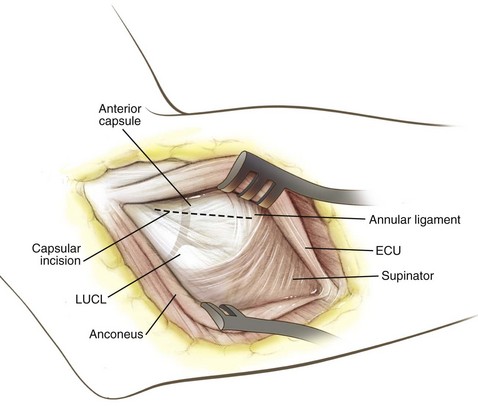

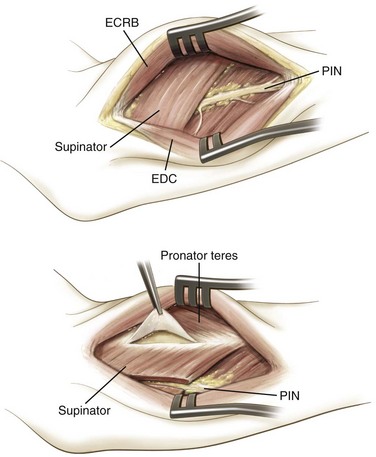

3. Lateral or posterolateral (Kocher’s) approach to the elbow (Figure 2-17)

Interval: between the anconeus (radial nerve) and the origin of the main extensor (extensor carpi ulnaris, posterior interosseous nerve [PIN])

Interval: between the anconeus (radial nerve) and the origin of the main extensor (extensor carpi ulnaris, posterior interosseous nerve [PIN])

Dissection: Pronate the arm to move the PIN anteriorly and radially, and approach the radial head through the proximal supinator fibers.

Dissection: Pronate the arm to move the PIN anteriorly and radially, and approach the radial head through the proximal supinator fibers.

Risks: Extending this approach distal to the annular ligament increases the risk for injury to the PIN.

Risks: Extending this approach distal to the annular ligament increases the risk for injury to the PIN.

4. Proximal extension of lateral approach

Interval: along lateral intercondylar ridge, between triceps and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) (brachioradialis nerve)

Interval: along lateral intercondylar ridge, between triceps and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) (brachioradialis nerve)

Dissection: Subperiosteally expose the anterior humerus and lateral column.

Dissection: Subperiosteally expose the anterior humerus and lateral column.

Risks: retractor placed under brachialis anteriorly to protect radial nerve, distally limited by PIN

Risks: retractor placed under brachialis anteriorly to protect radial nerve, distally limited by PIN

A Osteology: includes the ulna and radius, which articulate with the humerus (principally the ulna) and carpi (principally the radius)

Proximally, the ulna is composed of two curved processes, the olecranon and the coronoid processes, with an intervening trochlear notch.

Proximally, the ulna is composed of two curved processes, the olecranon and the coronoid processes, with an intervening trochlear notch.

Distally, the ulna tapers and ends in a lateral head and a medial styloid process.

Distally, the ulna tapers and ends in a lateral head and a medial styloid process.

Proximally, the radius is composed of a head with a central fovea, neck, and proximal medial radial tuberosity (for insertion of the biceps tendon).

Proximally, the radius is composed of a head with a central fovea, neck, and proximal medial radial tuberosity (for insertion of the biceps tendon).

It has a gradual bend (convex laterally) and gradually increases in size distally; restoration of the radial bow (and length) is paramount in the fixation of radial shaft fractures.

It has a gradual bend (convex laterally) and gradually increases in size distally; restoration of the radial bow (and length) is paramount in the fixation of radial shaft fractures.

Distally, the radius is composed of the carpal articular surface, an ulnar notch, a dorsal tubercle (Lister’s tubercle, which is at the level of the scapholunate joint), and a lateral styloid process.

Distally, the radius is composed of the carpal articular surface, an ulnar notch, a dorsal tubercle (Lister’s tubercle, which is at the level of the scapholunate joint), and a lateral styloid process.

B Arthrology: proximally includes the elbow joint (discussed earlier) and distally includes the wrist

1. Distal radioulnar articulation (most stable in supination)

This joint is ellipsoid and involves the distal radius and the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum.

This joint is ellipsoid and involves the distal radius and the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum.

It is usually located at the level of the crease of the proximal wrist flexion.

It is usually located at the level of the crease of the proximal wrist flexion.

Covered by a loose capsule, the wrist relies heavily on ligaments, especially volar ligaments, for stability.

Covered by a loose capsule, the wrist relies heavily on ligaments, especially volar ligaments, for stability.

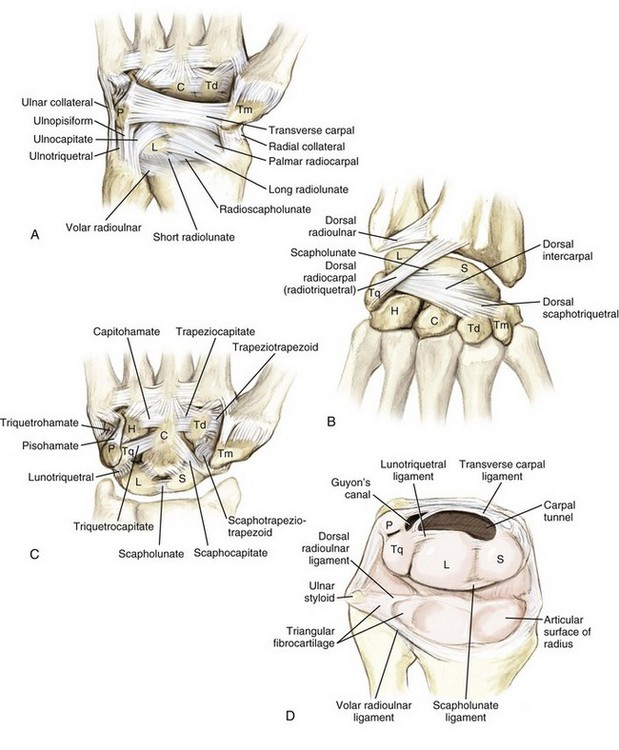

Ligaments about this joint are the volar and dorsal radiocarpal ligaments and the ulnar and radial collateral ligaments.

Ligaments about this joint are the volar and dorsal radiocarpal ligaments and the ulnar and radial collateral ligaments.

3. Triangular fibrocartilage complex (Figure 2-19): originates from the most ulnar portion of the radius and extends into the caput ulnae and the wrist aspect of the ulna to the base of the fifth metacarpal; includes the components listed in Table 2-20

Table 2-20

Components of the Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex

| Component | Origin | Insertion |

| Dorsal and volar radioulnar ligament | Ulnar radius | Caput ulnae |

| Articular disc | Radius/ulna | Triquetrum |

| Prestyloid recess | Disc | Meniscus homolog |

| Meniscus homolog | Ulna/disc | Triquetrum/ulnar collateral ligament |

| Ulnar collateral ligament | Ulna | Fifth metacarpal |

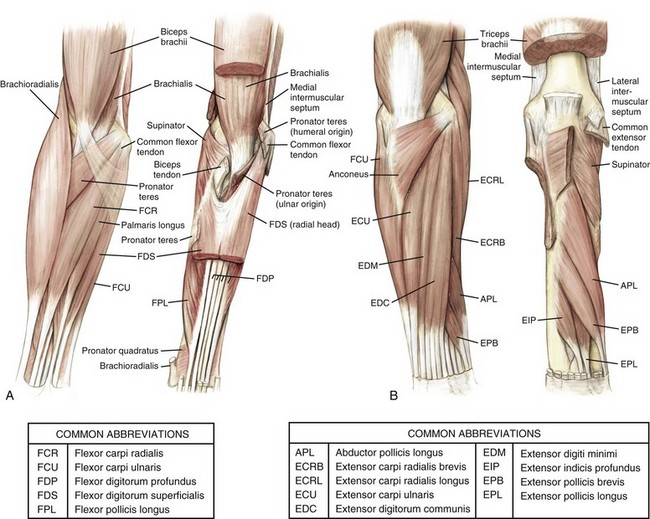

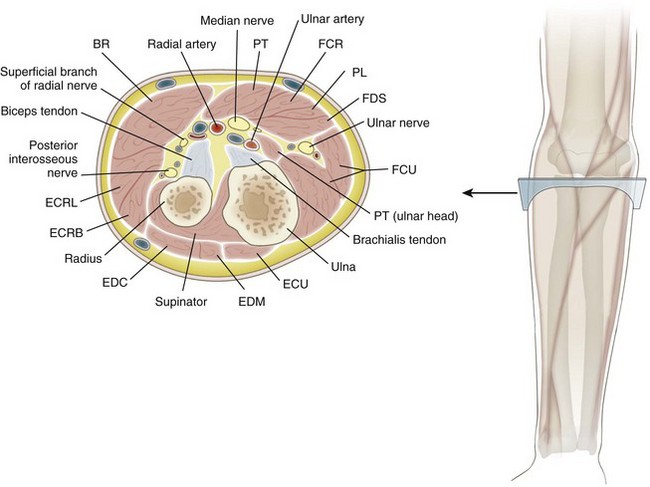

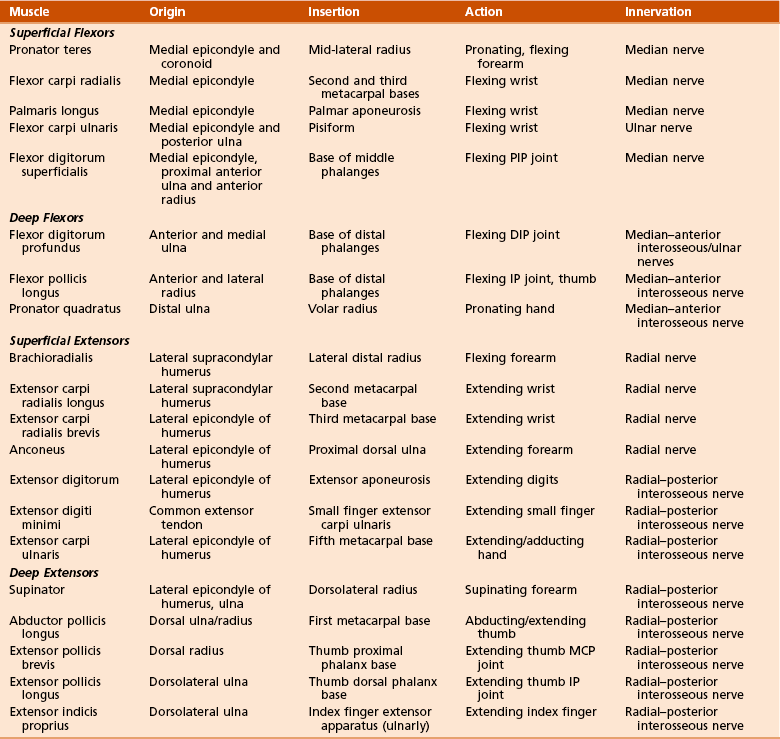

C Muscles (Figure 2-20 and Table 2-21): arranged according to both location and function

Table 2-21

1. Volar flexors (superficial and deep)

2. Dorsal extensors (superficial and deep): tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis) involves primarily the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB)

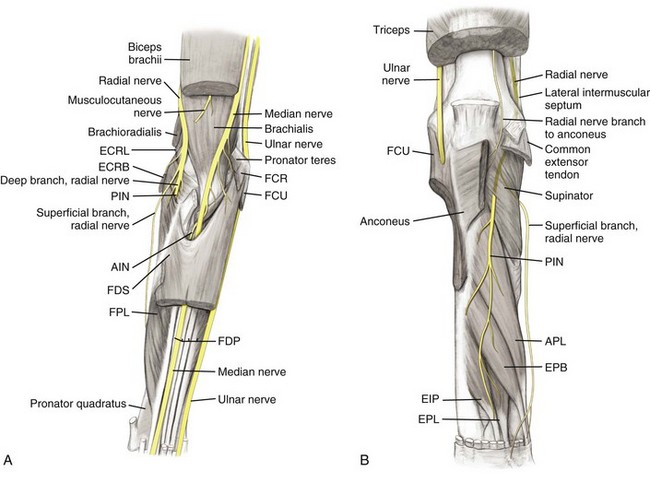

1. Anatomy: nerves of upper arm continue into the forearm (Figure 2-21, Table 2-22)

Table 2-22

Neuroanatomic Relationships in the Forearm

| Nerve | Relationships |

| Radial | Between brachialis and brachioradialis |

| Posterior interosseous | Splits supinator |

| Superficial radial | Between brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus |

| Median | Medial to brachial artery at elbow |

| Anterior interosseous | Splits pronator teres and runs between flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus Between flexor pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus |

| Ulnar | Between flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus |

This nerve is anterior to the lateral epicondyle.

This nerve is anterior to the lateral epicondyle.

It runs between the brachialis and brachioradialis and divides into the anterior and deep (PIN) branches.

It runs between the brachialis and brachioradialis and divides into the anterior and deep (PIN) branches.

The PIN splits the supinator and supplies all of the extensor muscles, except the mobile wad (brachioradialis, ECRB, ECRL).

The PIN splits the supinator and supplies all of the extensor muscles, except the mobile wad (brachioradialis, ECRB, ECRL).

Compression of the PIN can occur at six places (see in the section “Compressive Neuropathies of the Forearm”).

Compression of the PIN can occur at six places (see in the section “Compressive Neuropathies of the Forearm”).

The superficial branch of the radial nerve passes to the dorsal radial surface of the hand in the distal third of the forearm by passing between the brachioradialis and ECRL.

The superficial branch of the radial nerve passes to the dorsal radial surface of the hand in the distal third of the forearm by passing between the brachioradialis and ECRL.

This nerve is medial to the brachial artery at the elbow and superficial to the brachialis muscle.

This nerve is medial to the brachial artery at the elbow and superficial to the brachialis muscle.

In the forearm, the median nerve splits the two heads of the pronator teres and then runs between the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP).

In the forearm, the median nerve splits the two heads of the pronator teres and then runs between the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP).

It becomes more superficial at the flexor retinaculum, where it continues into the hand.

It becomes more superficial at the flexor retinaculum, where it continues into the hand.

It has branches to all the superficial flexor muscles of the forearm except the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU).

It has branches to all the superficial flexor muscles of the forearm except the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU).

The anterior interosseous branch, which runs between the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) and FDP, supplies all the deep flexors except the ulnar half of the FDP.

The anterior interosseous branch, which runs between the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) and FDP, supplies all the deep flexors except the ulnar half of the FDP.

Enters the forearm between the two heads of the FCU, which it supplies

Enters the forearm between the two heads of the FCU, which it supplies

Runs between the FCU and FDP, innervating the ulnar half of this muscle

Runs between the FCU and FDP, innervating the ulnar half of this muscle

Lies more superficial at the wrist and enters the hand through the Guyon canal

Lies more superficial at the wrist and enters the hand through the Guyon canal

Cutaneous nerves (see Figure 2-12)

Cutaneous nerves (see Figure 2-12)

Lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve: the continuation of the musculocutaneous nerve that passes lateral to the cephalic vein after emerging laterally from between the biceps and brachialis at the elbow

Lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve: the continuation of the musculocutaneous nerve that passes lateral to the cephalic vein after emerging laterally from between the biceps and brachialis at the elbow

Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve: a branch from the medial cord of the brachial plexus

Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve: a branch from the medial cord of the brachial plexus

Posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve:a branch of the radial nerve given off in the arm

Posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve:a branch of the radial nerve given off in the arm

2. Compressive neuropathies of the forearm (see Table 2-17)

An example of key testable material on compressive neuropathies would be to determine which muscle is last to return to function after the alleviation of PIN palsy.

An example of key testable material on compressive neuropathies would be to determine which muscle is last to return to function after the alleviation of PIN palsy.

PIN innervates the supinator, extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, abductor pollicis longus (APL), extensor pollicis longus (EPL), extensor pollicis brevis (EPB), and extensor indicis proprius, in that order.

PIN innervates the supinator, extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, abductor pollicis longus (APL), extensor pollicis longus (EPL), extensor pollicis brevis (EPB), and extensor indicis proprius, in that order.

Last muscle to return to function after PIN compression (extensor indicis proprius) is the most distally innervated muscle.

Last muscle to return to function after PIN compression (extensor indicis proprius) is the most distally innervated muscle.

Enters cubital fossa (bordered by the two epicondyles, the brachioradialis, and the pronator teres and overlying the brachialis and supinator)

Enters cubital fossa (bordered by the two epicondyles, the brachioradialis, and the pronator teres and overlying the brachialis and supinator)

Then divides at the level of the radial neck into the radial and ulnar arteries (Table 2-24)

Then divides at the level of the radial neck into the radial and ulnar arteries (Table 2-24)

Table 2-24

Vascular Anatomic Relationships in the Forearm

| Artery | Relationships |

| Radial | On pronator teres deep to brachioradialis Enters wrist between brachioradialis and flexor carpi radialis |

| Ulnar | Proximally between FDS and FDP Distally on FDP between flexor carpi ulnaris and FDS |

FDP, flexor digitorum profundus; FDS, flexor digitorum superficialis.

This artery initially runs on the pronator teres, deep to the brachioradialis.

This artery initially runs on the pronator teres, deep to the brachioradialis.

It continues to the wrist between this muscle and the flexor carpi radialis (FCR).

It continues to the wrist between this muscle and the flexor carpi radialis (FCR).

Forearm branches include the recurrent radial (see earlier discussion) and muscular branches.

Forearm branches include the recurrent radial (see earlier discussion) and muscular branches.

3. Ulnar artery: larger of the two branches

This artery is covered by the superficial flexors proximally (between the FDS and FDP).

This artery is covered by the superficial flexors proximally (between the FDS and FDP).

Distally, the artery lies on the FDP, between the tendons of the FCU and FDS.

Distally, the artery lies on the FDP, between the tendons of the FCU and FDS.

Forearm branches include the anterior and posterior recurrent ulnar (discussed earlier), the common interosseous (with anterior and posterior branches), and several muscular and nutrient arteries.

Forearm branches include the anterior and posterior recurrent ulnar (discussed earlier), the common interosseous (with anterior and posterior branches), and several muscular and nutrient arteries.

F Surgical approaches to the forearm (Table 2-25)

Table 2-25

Surgical Approaches to the Forearm

| Approach | Interval | Structures at Risk |

| Anterior (Henry’s) | Brachioradialis (radial nerve) and pronator teres (median nerve) Distally: flexor carpi radialis (median nerve) |

Ligate leash of Henry (radial artery branches) Superficial branch of radial nerve |

| Dorsal posterior (Thompson’s) | Extensor carpi radialis brevis (radial nerve) and extensor digitorum communis (PIN) Distally: extensor pollicis longus |

PIN: avoid excessive retraction of supinator |

| Ulnar | Extensor carpi ulnaris (PIN) and flexor carpi ulnaris (ulnar nerve) |

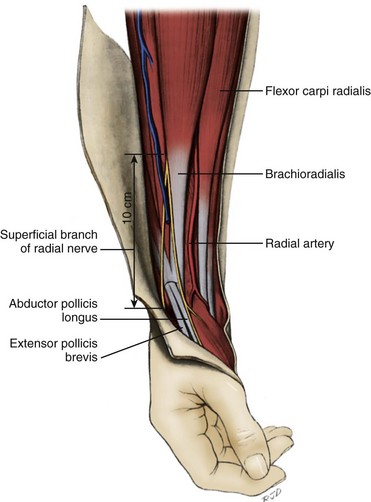

1. Anterior (Henry’s) approach (Figure 2-22)

Interval: between the brachioradialis (radial nerve) and pronator teres or FCR distally (median nerve)

Interval: between the brachioradialis (radial nerve) and pronator teres or FCR distally (median nerve)

Proximally: Isolate and ligate the leash of Henry (radial artery branches) proximally, and strip the supinator from its insertion subperiosteally; supination of the forearm displaces the PIN ulnarly.

Proximally: Isolate and ligate the leash of Henry (radial artery branches) proximally, and strip the supinator from its insertion subperiosteally; supination of the forearm displaces the PIN ulnarly.

Middle third: Pronate the forearm and incise the insertion of the pronator teres subperiosteally.

Middle third: Pronate the forearm and incise the insertion of the pronator teres subperiosteally.

The superficial branch of the radial nerve must be protected (retract laterally) with the brachioradialis.

The superficial branch of the radial nerve must be protected (retract laterally) with the brachioradialis.

The radial artery is at risk for injury proximally because it courses medial to the biceps tendon and distally with retraction of the brachioradialis.

The radial artery is at risk for injury proximally because it courses medial to the biceps tendon and distally with retraction of the brachioradialis.

The PIN can be injured during deep dissection of proximal exposure.

The PIN can be injured during deep dissection of proximal exposure.

2. Dorsal (posterior; Thompson’s) approach (Figure 2-23)

Interval: between the ECRB (radial nerve) and extensor digitorum or EPL distally (PIN)

Interval: between the ECRB (radial nerve) and extensor digitorum or EPL distally (PIN)

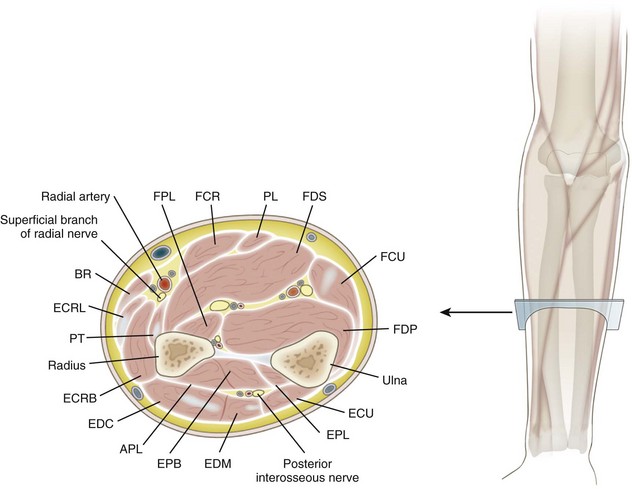

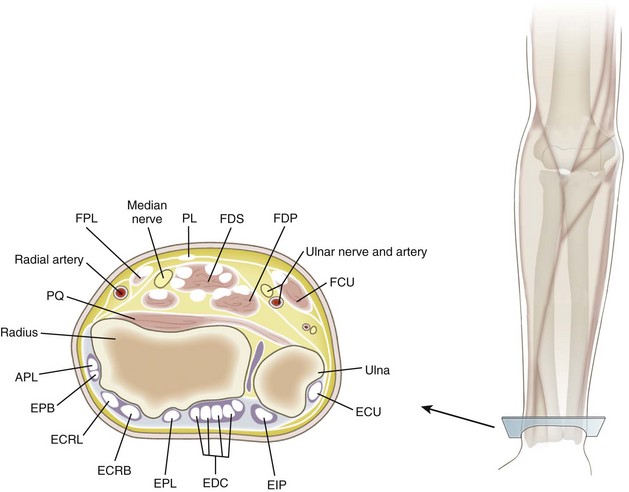

G Cross-sectional diagrams of proximal forearm (Figure 2-24), mid-forearm (Figure 2-25), and distal forearm (Figure 2-26)

Ossification begins at the capitate (usually present at 1 year of age) and proceeds in a counterclockwise direction, according to posteroanterior radiographs of the right hand.

Ossification begins at the capitate (usually present at 1 year of age) and proceeds in a counterclockwise direction, according to posteroanterior radiographs of the right hand.

Hamate is the second carpus to ossify (by ages 1 to 2 years).

Hamate is the second carpus to ossify (by ages 1 to 2 years).

Pisiform, which is a large sesamoid bone, is the last to ossify (by age 9 years).

Pisiform, which is a large sesamoid bone, is the last to ossify (by age 9 years).

Several key features are important to recognize in the individual carpal bones (Table 2-26).

Several key features are important to recognize in the individual carpal bones (Table 2-26).

Table 2-26

| Carpal Bone | Distinctive Features | Number of Articulations |

| Scaphoid | Tubercle (TCL, APB), distal vascular supply | 5 |

| Lunate | Half-moon–shaped | 5 |

| Triquetrum | Pyramid-shaped | 3 |

| Pisiform | Spheroidal (TCL, FCU) | 1 |

| Trapezium | FCR groove, tubercle (opponens, APB, flexor pollicis brevis, TCL) | 4 |

| Trapezoid | Wedge-shaped | 4 |

| Capitate | Largest bone, central location | 7 |

| Hamate | Hook (TCL) | 5 |

These bones have two ossification centers:

These bones have two ossification centers:

One for the body (primary center of ossification), which ossifies at 8 weeks of gestation (like most long bones)

One for the body (primary center of ossification), which ossifies at 8 weeks of gestation (like most long bones)

One at the neck, which usually appears before 3 years of age

One at the neck, which usually appears before 3 years of age

First metacarpal is a primordial phalanx, and its secondary ossification center is located at the base (like those of the phalanges).

First metacarpal is a primordial phalanx, and its secondary ossification center is located at the base (like those of the phalanges).

Several characteristics allow the identification of the individual metacarpals (Table 2-27).

Several characteristics allow the identification of the individual metacarpals (Table 2-27).

Table 2-27

| Metacarpal | Distinctive Features |

| I (Thumb) | Short, stout; base is saddle-shaped |

| II (Index) | Longest, largest base; medial at base |

| III (Middle) | Styloid process |

| IV (Ring) | Small quadrilateral base, narrow shaft |

| V (Small) | Tubercle at base (extensor carpi ulnaris) |

Each hand has 14 phalanges (three for each finger and two for the thumb), which are similar.

Each hand has 14 phalanges (three for each finger and two for the thumb), which are similar.

All have secondary ossification centers at their bases that appear at ages 3 years (proximal), 4 years (middle), and 5 years (distal).

All have secondary ossification centers at their bases that appear at ages 3 years (proximal), 4 years (middle), and 5 years (distal).

Bases of the proximal phalanges are oval and concave, with the smaller heads ending in two condyles.

Bases of the proximal phalanges are oval and concave, with the smaller heads ending in two condyles.

Middle phalanges have two concave facets at their bases and pulley-shaped heads.

Middle phalanges have two concave facets at their bases and pulley-shaped heads.

Distal phalanges are smaller and have palmar ungual tuberosities distally.

Distal phalanges are smaller and have palmar ungual tuberosities distally.

The wrist is an ellipsoid joint and made up of the distal radius, scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and ligamentous structures (Table 2-28).

The wrist is an ellipsoid joint and made up of the distal radius, scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and ligamentous structures (Table 2-28).

Table 2-28

| Structure | Attachments | Distinctive Features |

| Articular capsule | Surrounds joint | Reinforced by volar and dorsal radiocarpal ligament |

| Volar (radiocarpal ligament) | Radius, ulna, scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, capitate | Oblique ulnar, strong |

| Dorsal radiocarpal ligament | Radius, scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum | Oblique radial, weak |

| Ulnar collateral ligament | Ulna, triquetrum, pisiform, transverse carpal ligament | Fan-shaped, two fascicles |

| Radial collateral ligament | Radius, scaphoid, trapezium, transverse carpal ligament | Radial artery adjacent |

The palmar/volar radiocarpal ligament is the strongest supporting structure, although it has a weak area on the radial side (the space of Poirier) that lends less support to the scaphoid, lunate, and trapezoid (Figure 2-27).

The palmar/volar radiocarpal ligament is the strongest supporting structure, although it has a weak area on the radial side (the space of Poirier) that lends less support to the scaphoid, lunate, and trapezoid (Figure 2-27).

Scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum form gliding joints.

Scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum form gliding joints.

Two dorsal intercarpal ligaments connect the scaphoid and lunate and the lunate and triquetral bones.

Two dorsal intercarpal ligaments connect the scaphoid and lunate and the lunate and triquetral bones.

Two palmar intercarpal ligaments connect the scaphoid and lunate and the lunate and triquetral bones.

Two palmar intercarpal ligaments connect the scaphoid and lunate and the lunate and triquetral bones.

Dorsal intercarpal ligaments are stronger.

Dorsal intercarpal ligaments are stronger.

Interosseous ligaments are narrow bundles connecting the scaphoid and lunate and the lunate and triquetral bones.

Interosseous ligaments are narrow bundles connecting the scaphoid and lunate and the lunate and triquetral bones.

The pisotriquetral joint has a thin articular capsule.

The pisotriquetral joint has a thin articular capsule.

The ulnar collateral and palmar radiocarpal ligaments also connect the pisiform proximally.

The ulnar collateral and palmar radiocarpal ligaments also connect the pisiform proximally.

The pisohamate ligament and pisometacarpal ligaments help extend the pull of the FCU.

The pisohamate ligament and pisometacarpal ligaments help extend the pull of the FCU.

This row includes trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate gliding joints.

This row includes trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate gliding joints.

Dorsal intercarpal ligaments connect the trapezium with the trapezoid, the trapezoid with the capitate, and the capitate with the hamate.

Dorsal intercarpal ligaments connect the trapezium with the trapezoid, the trapezoid with the capitate, and the capitate with the hamate.

Interosseous ligaments are much thicker in the distal row, connecting the capitate and hamate (strongest), the capitate and trapezoid, and the trapezium and trapezoid (weakest).

Interosseous ligaments are much thicker in the distal row, connecting the capitate and hamate (strongest), the capitate and trapezoid, and the trapezium and trapezoid (weakest).

3. Carpometacarpal (CMC) joints

This structure covers the dorsum of the wrist and contains six synovial sheaths (Figure 2-28).

This structure covers the dorsum of the wrist and contains six synovial sheaths (Figure 2-28).

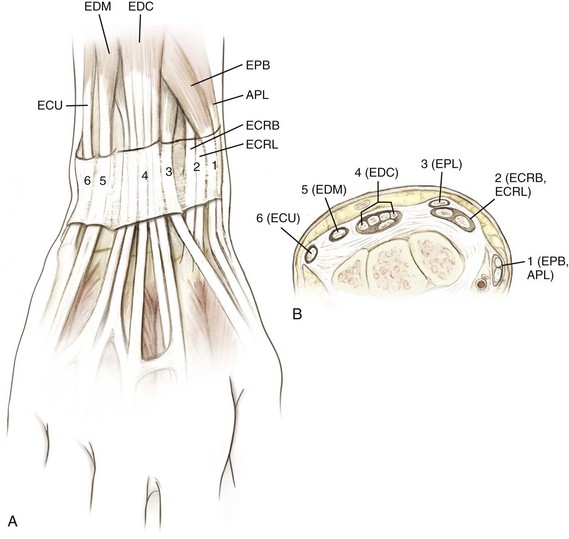

Figure 2-28 Extensor compartments of the wrist (1 to 6). See Table 2-29. APL, abductor pollicis longus; ECRB, extensor carpi radialis brevis; ECRL, extensor carpi radialis longus; ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris; EDC, extensor digitorum communis; EDM, extensor digiti minimi; EPB, extensor pollicis brevis; EPL, extensor pollicis longus. (Modified from Miller MD, et al: Orthopaedic surgical approaches, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders, Figure HW-6.)

Orientation of the extensor tendons at the wrist is a key testable item (Table 2-29).

Orientation of the extensor tendons at the wrist is a key testable item (Table 2-29).

Table 2-29

| Compartment | Contents | Pathologic Condition |

| I | Abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis | De Quervain’s tenosynovitis |

| II | Extensor carpi radialis longus, brevis | Extensor tendinitis (intersection syndrome) |

| III | Extensor pollicis longus | Rupture at Lister’s tubercle (after wrist fractures) Drummer’s tendinitis of the wrist |

| IV | Extensor digitorum communis, extensor indicis proprius | Extensor tenosynovitis |

| V | Extensor digiti minimi | Rupture (rheumatoid arthritis: Vaughn-Jackson syndrome) |

| VI | Extensor carpi ulnaris | Snapping at ulnar styloid |

The first dorsal compartment contains the APL and the EPB.

The first dorsal compartment contains the APL and the EPB.

The EPB tendon is ulnar to the APL tendon (the APL frequently has multiple tendon slips, which should be addressed during release for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis).

The EPB tendon is ulnar to the APL tendon (the APL frequently has multiple tendon slips, which should be addressed during release for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis).

In the second dorsal compartment, the ECRL tendon is radial to the ECRB tendon. Thus, the EPL tendon is ulnar to the ECRB tendon at the wrist level.

In the second dorsal compartment, the ECRL tendon is radial to the ECRB tendon. Thus, the EPL tendon is ulnar to the ECRB tendon at the wrist level.

The anatomic snuffbox is bordered by tendons of the first and third dorsal wrist compartments; the EPB tendon serves as the radial snuffbox border, and the EPL tendon serves as the ulnar border.

The anatomic snuffbox is bordered by tendons of the first and third dorsal wrist compartments; the EPB tendon serves as the radial snuffbox border, and the EPL tendon serves as the ulnar border.

The posterior interosseous nerve is contained within the floor of the fourth dorsal wrist compartment.

The posterior interosseous nerve is contained within the floor of the fourth dorsal wrist compartment.

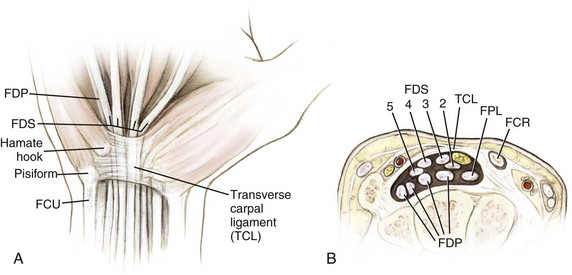

Transverse carpal ligament (TCL)

Transverse carpal ligament (TCL)

This is one component of the flexor retinaculum, which serves as the roof of the carpal tunnel (Figure 2-29).

This is one component of the flexor retinaculum, which serves as the roof of the carpal tunnel (Figure 2-29).

It is attached medially to the pisiform and the hook of the hamate and laterally to the tuberosity of the scaphoid and the ridge of the trapezium.

It is attached medially to the pisiform and the hook of the hamate and laterally to the tuberosity of the scaphoid and the ridge of the trapezium.

Carpal tunnel decreases in volume with wrist flexion.

Carpal tunnel decreases in volume with wrist flexion.

This tunnel contains the median nerve and nine tendons (one FPL, four FDS, and four FDP).

This tunnel contains the median nerve and nine tendons (one FPL, four FDS, and four FDP).

In the tunnel, the FDS tendons of the middle and ring fingers are volar to the tendons of the index and small fingers.

In the tunnel, the FDS tendons of the middle and ring fingers are volar to the tendons of the index and small fingers.

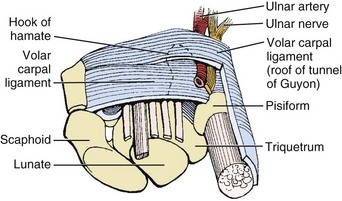

The flexor retinaculum also forms the floor of Guyon’s canal, which is bordered as well by the hook of the hamate and the pisiform and is covered by the volar carpal ligament; the ulnar nerve can become entrapped in this canal (Figure 2-30).

The flexor retinaculum also forms the floor of Guyon’s canal, which is bordered as well by the hook of the hamate and the pisiform and is covered by the volar carpal ligament; the ulnar nerve can become entrapped in this canal (Figure 2-30).

Triangular fibrocartilage complex

Triangular fibrocartilage complex

This complex is formed by the triangular fibrocartilage, ulnocarpal ligaments (volar ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral ligaments), and a meniscal homolog.

This complex is formed by the triangular fibrocartilage, ulnocarpal ligaments (volar ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral ligaments), and a meniscal homolog.

Injury to this structure is a common cause of ulnar wrist pain (see Figure 2-19).

Injury to this structure is a common cause of ulnar wrist pain (see Figure 2-19).

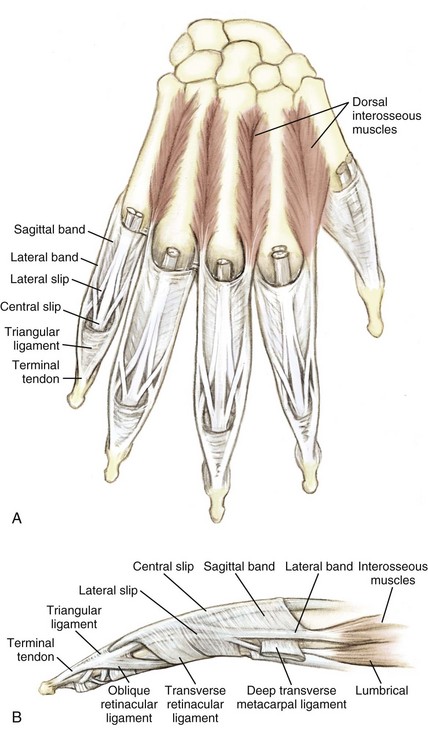

Intrinsic apparatus (Table 2-30)

Intrinsic apparatus (Table 2-30)

Table 2-30![]()

| Structure | Attachments | Significance |

| Sagittal bands | Covers MCP joint | Allows MCP extension |

| Transverse (sagittal) | Volar plate fibers | Allows MCP flexion (interossei) |

| Lateral bands | Covers PIP joint | Allows PIP extension (lumbrical muscles) |

| Oblique retinacular ligament (Landsmeer) | A4 pulley, terminal tendon | Allows DIP extension (passive) |

A4, annular 4; DIP, distal interphalangeal; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

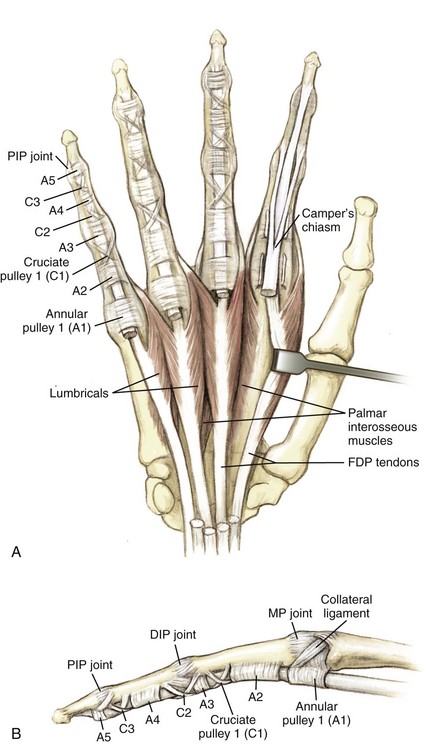

This covers the flexor tendons in the finger, protecting and nourishing the tendons (vincula).

This covers the flexor tendons in the finger, protecting and nourishing the tendons (vincula).

It forms five annular pulleys (A1 to A5) with three intervening cruciate attachments (C1 to C3).

It forms five annular pulleys (A1 to A5) with three intervening cruciate attachments (C1 to C3).

A2 and A4 pulleys originate from bone, whereas A1, A3, and A5 pulleys originate from the palmar plates of the metacarpal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints.

A2 and A4 pulleys originate from bone, whereas A1, A3, and A5 pulleys originate from the palmar plates of the metacarpal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints.

The A2 pulley, overlying the proximal phalanx, is the most critical to function, followed by A4, which covers the middle phalanx.

The A2 pulley, overlying the proximal phalanx, is the most critical to function, followed by A4, which covers the middle phalanx.

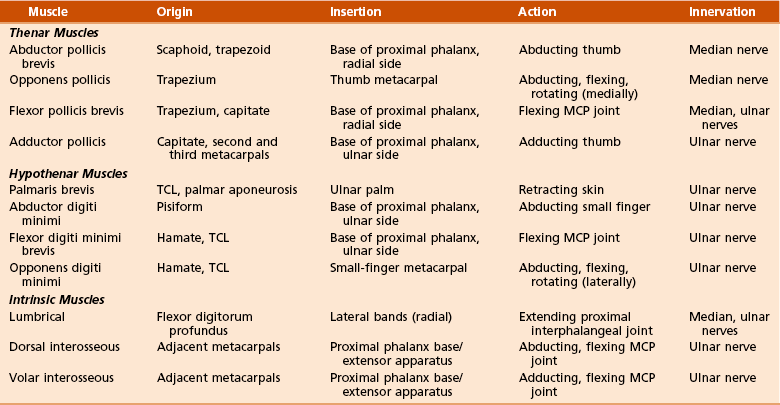

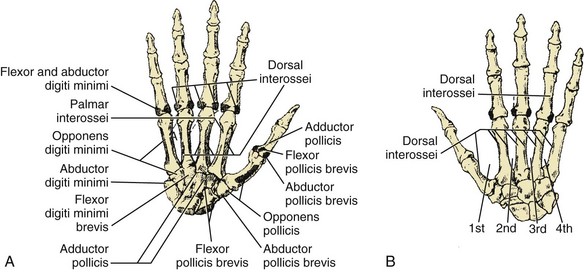

C Muscles (Table 2-31); origins and insertions (Figure 2-33)

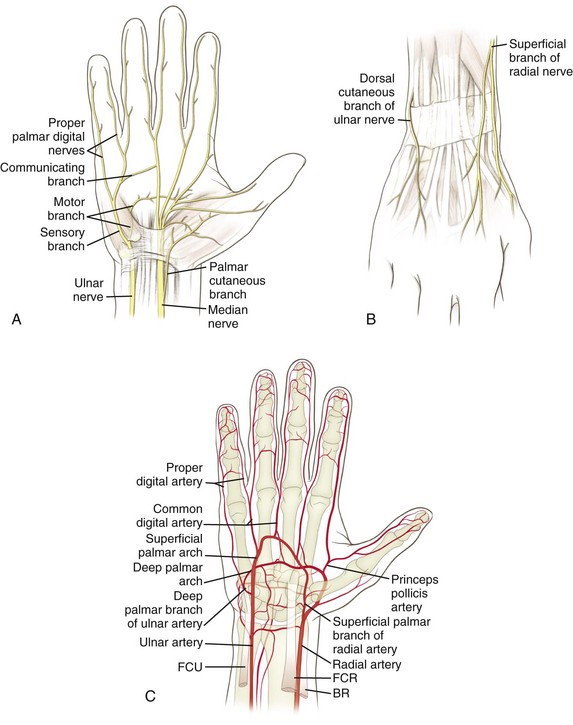

This nerve enters the wrist just under the TCL, between the FDS and FCR.

This nerve enters the wrist just under the TCL, between the FDS and FCR.

The palmar cutaneous branch, which arises proximal to the TCL between the palmaris longus and FCR, innervates the thenar skin.

The palmar cutaneous branch, which arises proximal to the TCL between the palmaris longus and FCR, innervates the thenar skin.

The deep (muscular) branch runs radially and innervates the thenar muscles.

The deep (muscular) branch runs radially and innervates the thenar muscles.

The digital nerves innervate the lumbrical muscles and the volar aspect of the radial three and a half digits.

The digital nerves innervate the lumbrical muscles and the volar aspect of the radial three and a half digits.

This nerve enters the wrist through Guyon’s canal and divides into a superficial branch (palmaris brevis and skin) and a deep branch.

This nerve enters the wrist through Guyon’s canal and divides into a superficial branch (palmaris brevis and skin) and a deep branch.

The deep branch travels with the deep palmar arch and passes between the abductor digiti minimi and flexor digiti minimi brevis, giving off motor branches to the deep musculature (three hypothenar muscles, two ulnar lumbrical muscles, all interossei, and the adductor pollicis) and terminating in digital nerves for the ulnar one and a half digits.

The deep branch travels with the deep palmar arch and passes between the abductor digiti minimi and flexor digiti minimi brevis, giving off motor branches to the deep musculature (three hypothenar muscles, two ulnar lumbrical muscles, all interossei, and the adductor pollicis) and terminating in digital nerves for the ulnar one and a half digits.

The dorsal cutaneous branch swings dorsally at the wrist and can be injured by either arthroscopic portal placement or surgical incision.

The dorsal cutaneous branch swings dorsally at the wrist and can be injured by either arthroscopic portal placement or surgical incision.

2. Innervation of the wrist and hand (Table 2-32)

Table 2-32

Innervation of the Wrist and Hand

| Nerve | Muscles Innervated |

| Median (medial and lateral cord) | Abductor pollicis brevis, superficial head of flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, first and second lumbrical muscles |

| Ulnar (medial cord) | Abductor digiti minimi, opponens digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi, third and fourth lumbrical muscles, interossei, adductor pollicis, deep head of flexor pollicis brevis |

At the wrist, the radial artery reaches the dorsum of the carpus by passing between (1) the FCR and (2) the APL and EPB tendons (snuffbox).

At the wrist, the radial artery reaches the dorsum of the carpus by passing between (1) the FCR and (2) the APL and EPB tendons (snuffbox).

Before that, it gives off a superficial palmar branch that communicates with the superficial arch (ulnar artery).

Before that, it gives off a superficial palmar branch that communicates with the superficial arch (ulnar artery).

It forms the deep palmar arch in the hand.

It forms the deep palmar arch in the hand.

The dorsal carpal branch of the radial artery enters the scaphoid dorsally and distally.

The dorsal carpal branch of the radial artery enters the scaphoid dorsally and distally.

F Surgical approaches to the wrist and hand (Table 2-33)

Table 2-33

Surgical Approaches to the Wrist

| Approach | Interval | Structures at Risk |

| Dorsal wrist | Third (extensor pollicis longus) and fourth (extensor digitorum communis) compartments | Transection of the innervation of the posterior interosseous nerve to the wrist capsule can be performed |

| Volar wrist | Flexor carpi radialis | Palmar cutaneous branch of median nerve |

| Volar scaphoid | Flexor carpi radialis and radial artery | Radial artery |

| Dorsolateral scaphoid | First and third compartments | Superficial radial nerve and radial artery |

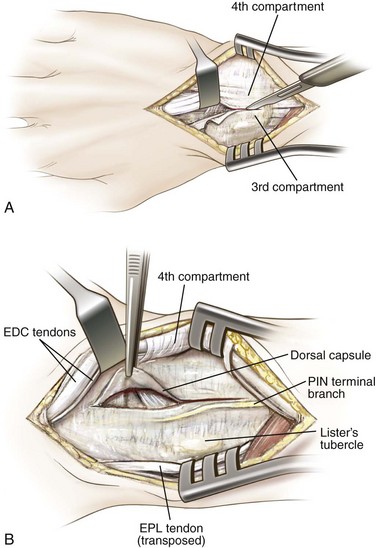

1. Dorsal approach to the wrist (Figure 2-35)

Interval: between the third and fourth extensor compartments (EPL and extensor digitorum)

Interval: between the third and fourth extensor compartments (EPL and extensor digitorum)

Incise the extensory retinaculum between the third and fourth compartments.

Incise the extensory retinaculum between the third and fourth compartments.

Protect and retract these tendons to allow access to the distal radius and the dorsal radiocarpal joint.

Protect and retract these tendons to allow access to the distal radius and the dorsal radiocarpal joint.

Risks: Do not violate the interosseous scapholunate ligament.

Risks: Do not violate the interosseous scapholunate ligament.

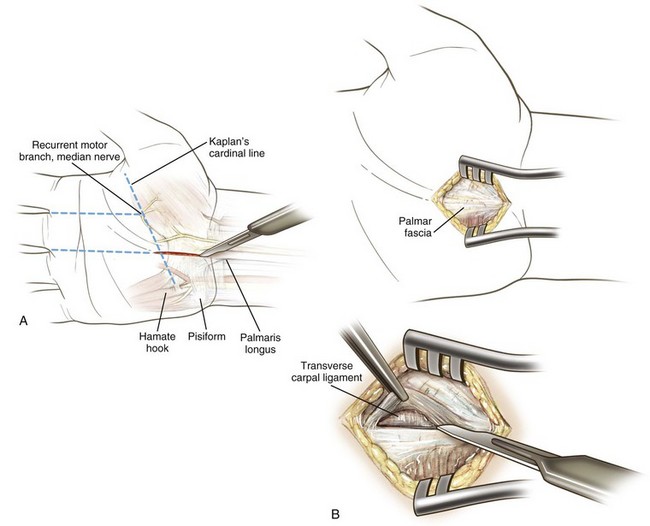

2. Carpal tunnel release (Figure 2-36)

Incision is usually made in line with the fourth ray to avoid the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve.

Incision is usually made in line with the fourth ray to avoid the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve.

Dissection through the TCL must be performed carefully in order to avoid injury to the median nerve or its motor branch.

Dissection through the TCL must be performed carefully in order to avoid injury to the median nerve or its motor branch.

3. Volar (Russé’s) approach to the scaphoid

Interval: between the FCR and radial artery

Interval: between the FCR and radial artery

An approach through the radial aspect of the FCR sheath: often easier and protects the radial artery

An approach through the radial aspect of the FCR sheath: often easier and protects the radial artery

4. Dorsolateral approach to the scaphoid

Using an incision within the anatomic snuffbox (first and third dorsal wrist compartment) helps protect the superficial radial nerve and radial artery (deep).

Using an incision within the anatomic snuffbox (first and third dorsal wrist compartment) helps protect the superficial radial nerve and radial artery (deep).

section 3 Spine

1. Thirty-three vertebrae: 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 fused sacral, and 4 fused coccygeal

Normal curves are cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, and sacral kyphosis.

Normal curves are cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, and sacral kyphosis.

Vertebral bodies generally increase in width in a craniocaudad direction, with the exception of T1 to T3.

Vertebral bodies generally increase in width in a craniocaudad direction, with the exception of T1 to T3.

Important spine topographic landmarks are listed in Table 2-34.

Important spine topographic landmarks are listed in Table 2-34.

Table 2-34![]()

| Topographic Landmark | Spinal Level |

| Mandible | C2-C3 |

| Hyoid cartilage | C3 |

| Thyroid cartilage | C4-C5 |

| Cricoid cartilage | C6 |

| Vertebra prominens | C7 |

| Scapular spine | T3 |

| Distal tip of scapula | T7 |

| Iliac crest | L4-L5 |

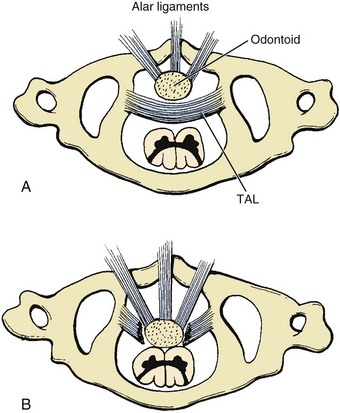

The atlas (C1) has no vertebral body and no spinous process.

The atlas (C1) has no vertebral body and no spinous process.

Highest percentage of neck flexion and extension occurs at the occiput-C1 articulation (50% of the total).

Highest percentage of neck flexion and extension occurs at the occiput-C1 articulation (50% of the total).

Axis (C2) develops from five ossification centers, with an initial cartilaginous junction between the dens and vertebral body (subdental synchondrosis) that fuses at 7 years of age.

Axis (C2) develops from five ossification centers, with an initial cartilaginous junction between the dens and vertebral body (subdental synchondrosis) that fuses at 7 years of age.

Atlantoaxial articulation is responsible for the majority of neck rotation; 50% of total rotation occurs at the C1-C2 articulation.

Atlantoaxial articulation is responsible for the majority of neck rotation; 50% of total rotation occurs at the C1-C2 articulation.

Atlantoaxial joint is diarthrodial.

Atlantoaxial joint is diarthrodial.

Pannus in rheumatoid arthritis can affect this articulation and result in instability (see Chapter 8, Spine).

Pannus in rheumatoid arthritis can affect this articulation and result in instability (see Chapter 8, Spine).

Cervical spine clearance including radiographs is recommended for elective orthopaedic procedures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Cervical spine clearance including radiographs is recommended for elective orthopaedic procedures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

C2 to C7 vertebrae have foramina in each transverse process and bifid spinous processes (except for the C7 nonbifid posterior spinous process [vertebral prominens]).

C2 to C7 vertebrae have foramina in each transverse process and bifid spinous processes (except for the C7 nonbifid posterior spinous process [vertebral prominens]).

The vertebral artery travels in the transverse foramina of C6 to C1.

The vertebral artery travels in the transverse foramina of C6 to C1.

Carotid (Chassaignac’s) tubercle is found at C6.

Carotid (Chassaignac’s) tubercle is found at C6.

The diameter of the cervical spine canal is normally 17 mm, and the cervical cord may become compromised when the diameter is reduced to less than 13 mm.

The diameter of the cervical spine canal is normally 17 mm, and the cervical cord may become compromised when the diameter is reduced to less than 13 mm.

Unique features include costal facets (present on all 12 vertebral bodies and the transverse processes of T1 to T9) and a rounded vertebral foramen.

Unique features include costal facets (present on all 12 vertebral bodies and the transverse processes of T1 to T9) and a rounded vertebral foramen.

Thoracic vertebral articulation with the rib cage makes this the most rigid region of the axial skeleton.

Thoracic vertebral articulation with the rib cage makes this the most rigid region of the axial skeleton.

Lumbar vertebrae are the largest vertebrae and are higher anteriorly than posteriorly, significantly contributing to the lumbar lordosis.

Lumbar vertebrae are the largest vertebrae and are higher anteriorly than posteriorly, significantly contributing to the lumbar lordosis.

Lumbar lordosis ranges from 55 to 60 degrees, with the apex at L3; 66% of lordosis occurs in the region from L4 to the sacrum.

Lumbar lordosis ranges from 55 to 60 degrees, with the apex at L3; 66% of lordosis occurs in the region from L4 to the sacrum.

Lumbar vertebrae contain short laminae and pedicles.

Lumbar vertebrae contain short laminae and pedicles.

Mammillary processes (separate ossification centers) project posteriorly from the superior articular facet.

Mammillary processes (separate ossification centers) project posteriorly from the superior articular facet.

Spondylolysis is a defect in the pars interarticularis and the most common cause of back pain in children and adolescents.

Spondylolysis is a defect in the pars interarticularis and the most common cause of back pain in children and adolescents.

The sacrum is formed from the fusion of five spinal elements.

The sacrum is formed from the fusion of five spinal elements.

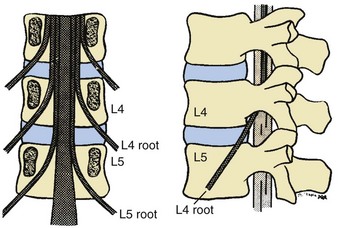

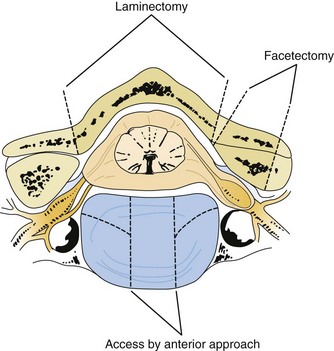

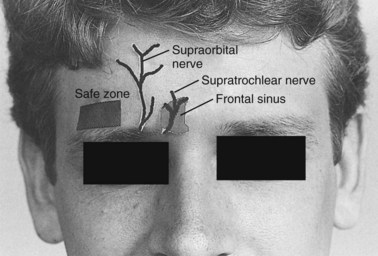

The sacral promontory is an anterosuperior portion that projects into the pelvis.