Anatomic and Physiologic Aspects of the Pulmonary Parenchyma

Chapters 8 through 11 focus on the region of the lung directly involved in gas exchange, often called the pulmonary parenchyma. This region includes the alveolar walls and spaces (with the alveolar-capillary interface) at the level of the alveolar sacs, ducts, and respiratory bronchioles. Although the broad group of disorders involving these structures traditionally has been described under the rubric of interstitial lung disease, the term diffuse parenchymal lung disease is increasingly used and more accurately reflects the breadth of the pathologic involvement.

This chapter provides a description of the normal anatomy of the gas-exchanging region of the lung and some aspects of its normal physiology. Chapter 9 provides an overview of the diffuse parenchymal lung diseases, emphasizing how disturbances in alveolar structure are closely linked with aberrations in function. Chapters 10 and 11 focus on specific disorders, generally subacute or chronic, the main pathologic features of which appear to reside within the alveolar wall. Pneumonia, acute lung injury (acute respiratory distress syndrome), and diseases of the pulmonary vasculature are deliberately excluded because of their different pathologic appearance and are considered separately in other parts of this text.

Anatomy

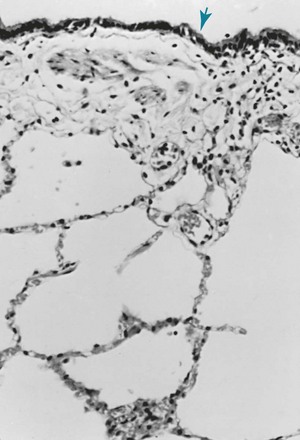

For the lung to function efficiently as a gas-exchanging organ, a large surface area must be available where O2 can be taken up and CO2 released. At the alveolar wall, where gas exchange occurs, an extensive network of capillaries coursing through and coming into close contact with alveolar gas facilitates the exchange. In the normal lung, the capillaries are closely apposed to the alveolar lumen, and there is little tissue extraneous to the gas-exchanging process (Fig. 8-1).

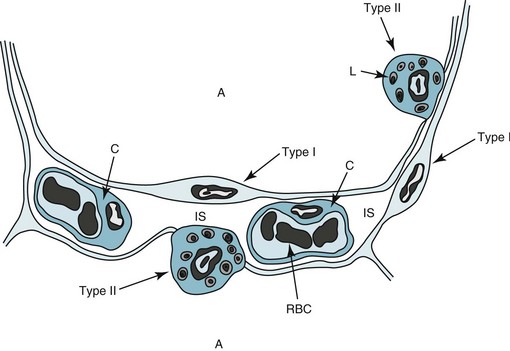

The surface of the alveolar walls (the region bordering the alveolar lumen) is lined by a continuous layer of epithelial cells. Two different types of these lining epithelial cells, called type I and type II cells, can be identified. Type I cells are less numerous than type II cells but account for a much larger surface area. They have impressively long and delicate cytoplasmic extensions that line more than 95% of the alveolar surface (Fig. 8-2). Type I cells function as a barrier preventing free movement of material, such as fluid, from the alveolar wall into the alveolar lumen. Although they have few cytoplasmic organelles, increasing evidence indicates that type I cells play an important role in the regulation of ion and fluid balance in the lung, in part because they cover such a large part of the alveolar surface area.

The primary product of the type II cells is surfactant. Specific inclusion bodies within the type II cells, termed lamellar inclusions, appear to be the packaged form of surfactant that eventually is released into the alveolar lumen. Surfactant is composed of a high proportion of lipids as well as associated proteins and carbohydrates that are necessary for effective function. Surfactant acts like a detergent, reducing the surface tension of the alveoli. It stabilizes the alveolus in the same way a bubble is prevented from collapsing by a detergent material, thereby preventing microatelectasis (alveolar collapse on a microscopic level). Four types of protein are associated with surfactant: surfactant protein A, B, C, and D (SP-A, SP-B, SP-C, and SP-D, respectively). The function of surfactant in maintaining a low surface tension is critically dependent on the hydrophobic proteins SP-B and SP-C. Although SP-A and SP-D also affect surface tension, they additionally have an important role in the innate immunity of the lung by opsonizing and directly killing some microbial pathogens (see Chapter 22).

Type II cells have a significant role in maintenance and repair of the injured alveolar epithelium. Type I epithelial cells are quite susceptible to injury, whether from an external source via the airways or an internal source via the bloodstream. When type I cells are damaged, the reparative process involves hyperplasia of the type II cells and eventual differentiation into cells with the characteristics of type I cells. Normally, this orderly process results in some hyperplastic type II cells undergoing apoptosis, while the remainder transdifferentiate into thin, delicate, type I cells. As discussed in Chapter 11, defects in this process have been identified in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a devastating disease of progressive parenchymal scarring.

Pulmonary capillaries course through the alveolar walls as part of an extensive network of intercommunicating vessels. Unlike the alveolar epithelial cells, which are quite impermeable under normal circumstances, junctions between capillary endothelial cells permit passage of small-molecular-weight proteins. The importance of the permeability features of the alveolar epithelial and capillary endothelial cells will become apparent in the discussion of acute respiratory distress syndrome in Chapter 28, because this disorder is characterized by increased permeability and leakage of fluid and protein into alveolar spaces.

The alveolar epithelial and capillary endothelial cells rest on a basement membrane. At some regions of the alveolar wall, nothing stands between the epithelial and endothelial cells other than the basement membranes, which are fused to form a single structure. At other regions, the interstitial space, which consists of relatively acellular material (see Fig. 8-2), intervenes. The major components of the interstitial space are collagen, elastin, proteoglycans, a variety of macromolecules involved with cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, some nerve endings, and some fibroblast-like cells. There are also small numbers of lymphocytes as well as cells that appear to be in a transition state between blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages (which are derived from circulating monocytes).

Within the alveolar lumen, a thin layer of liquid covers the alveolar epithelial cells. This extracellular alveolar lining layer is composed of an aqueous phase immediately adjacent to the epithelial cells, covered by a surface layer of lipid-rich surfactant produced by the type II epithelial cells. The alveolar lining layer also contains alveolar macrophages, phagocytic cells that are important in protecting the distal lung against bacteria and in clearing inhaled particulate matter. Alveolar macrophages and the innate immunity of the lung are discussed further in Chapter 22.

Physiology

Some of the physiologic principles relating to the pulmonary parenchyma were covered briefly in Chapter 1. This chapter further discusses two topics that are important in the pathophysiologic abnormalities resulting from diffuse parenchymal lung disease. This section reviews gas exchange at the alveolar-capillary level, followed by a discussion of how disturbances within the pulmonary parenchyma affect the mechanical properties of the lung.

Gas exchange between the alveolus and the capillary depends on passive diffusion of gas from a region of higher partial pressure to one of lower partial pressure. As discussed in Chapter 1, the PO2 in the alveolus normally is approximately 100 mm Hg, and in the blood entering the pulmonary capillary is approximately 40 mm Hg. This difference results in a driving pressure for O2 to diffuse from the alveolus to the pulmonary capillary, where it binds with hemoglobin within the erythrocyte. The barrier to diffusion—which includes the thin cytoplasmic extension of the type I cell, the basement membrane of type I and capillary endothelial cells, and the capillary endothelial cell itself—is extremely thin, measuring approximately 0.5 µm. Some areas of the alveolar wall also contain a thin layer of interstitium, but presumably diffusion and gas exchange occur preferentially at the thinnest region, where the interstitium is sparse or absent.

Consequently, although diffuse parenchymal lung diseases do affect gas exchange, impaired diffusion across an abnormal alveolar-capillary interface is not a primary contributor to the disturbance in gas exchange when the patient is at rest. However, when these patients exercise and cardiac output increases, blood flows more rapidly through the pulmonary capillaries, and the combination of a diffusion impairment and a shorter time for diffusion of oxygen may lead to hypoxemia. This issue is considered further in Chapter 9 as part of the discussion of abnormalities in gas exchange in patients with diseases affecting the alveolar wall.

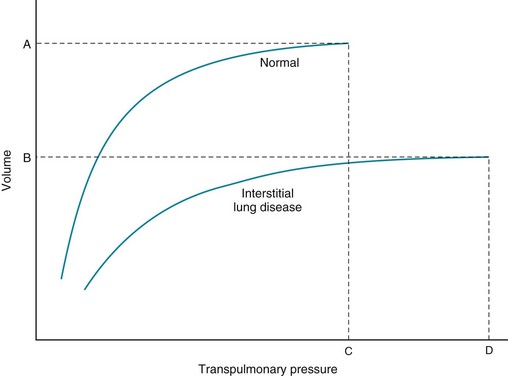

Another important aspect of physiology relating to the lung parenchyma is compliance or, described more simply, the opposite of the stiffness of the lung. As stated in Chapter 1, the lung is elastic and behaves like a balloon or a rubber band in terms of resisting expansion. During inspiration, contraction of the diaphragm and expansion of the thorax by respiratory muscle function result in negative pressure around the lungs, causing them to expand. Conversely, positive pressure may be applied through the airways to inflate the lungs, as occurs during positive pressure mechanical ventilation. For any given volume of air in the lungs, a certain pressure is required to achieve this degree of inflation, and a curve can be drawn relating volume on the y-axis to pressure on the x-axis (see Fig. 1-3, A). Because the net pressure producing expansion is the difference between the pressure exerted on the alveoli (via the airway) and the absolute pressure outside the lung, the term transpulmonary pressure is used to describe this distending pressure. In vivo, when the lung is sitting within the chest, the pressure outside the lung is pleural pressure. If a lung is removed and studied in isolation, the pressure outside the lung is atmospheric pressure. The normal compliance relationship between volume and pressure in the lung is a curve that flattens out at high distending pressures when the lung reaches its upper limit of expansion. At this point the elastic tissues of the lung can be stretched no further, and additional pressure does not add volume to the lung.

Diseases affecting the alveolar walls commonly disturb this pressure-volume relationship, making the lung either more stiff (more resistant to expansion) or less stiff (easier to expand). For the stiffer, less compliant lung, the compliance curve is shifted to the right: a lower volume is achieved for any given transpulmonary pressure. Most of the diseases discussed in this section, which are included in the category of diffuse parenchymal lung disease, affect the compliance of the lung in this way (Fig. 8-3). In contrast, as discussed in Chapter 6 and illustrated in Figure 6-7, patients with emphysema, whose lungs are less resistant to expansion (i.e., are more compliant), have compliance curves that are shifted to the left. This principle of compliance is important in pulmonary physiology. Chapters 1 and 6 alluded to the role of compliance in determining lung volumes measured by pulmonary function testing, particularly total lung capacity and functional residual capacity. This principle is cited again Chapter 9, which discusses the pathophysiology of diseases that affect the alveolar walls.

Figure 8-3 Compliance curve of lung in interstitial lung disease compared with that of normal lung. In addition to shift of the curve downward and to right, total lung capacity (TLC) in interstitial lung disease (point B on volume axis) is characteristically less than normal TLC (point A). Maximal pressure at TLC is called maximal static recoil pressure (Pstmax), represented for normal lung and lung with interstitial disease by points C and D, respectively. (Compare with Figure 6-7.)

Albertine, KH. Anatomy of the lungs. In: Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Martin T, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel’s textbook of respiratory medicine. ed 5. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010:3–25.

Beers, MF, Morrisy, EE. The three R’s of lung health and disease: repair, remodeling and regeneration. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2065–2073.

Mason, RJ. Biology of alveolar type II cells. Respirology. 2006;11(Suppl):S12–S15.

Sayner, SL. Emerging themes of cAMP regulation of the pulmonary endothelial barrier. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L667–678.

Whitsett, JA. Surfactant proteins in innate host defense of the lung. Biol Neonate. 2005;88:175–180.

Whitsett, JA, Weaver, TE. Hydrophobic surfactant proteins in lung function and disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2141–2148.