Chapter 50 Anal Carcinoma

Carcinoma of the anal canal accounts for about 1.9% of all malignant tumors of the digestive system in patients in the United States.1 Despite the rarity of anal cancer, it is a model for successful oncology research, both in the laboratory and in the clinic. Epidemiologic observations about the increased incidence of anal cancer in some populations, along with advances in molecular biology that have allowed the identification of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in most anal tumors, have provided the initial clues to the mechanism of anal carcinogenesis. Retrospective studies have provided important information about the natural history and patterns of spread of anal cancer, as well as hypotheses to test in prospective trials. Prospective randomized trials have been completed successfully and have led to the adoption of a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy as the standard of care for patients with anal cancer. Questions remain, however, about the most effective and least toxic regimens of radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Anal cancer occurs much less frequently than other types of cancer of the digestive tract. It accounts for only 2% to 4% of all cancers of the anus or rectum.2,3,4,5 In the United States, the annual incidence is 0.47 per 100,000 white men and 0.69 per 100,000 white women.6 The annual incidence among African Americans is higher: 0.57 per 100,000 men and 0.78 per 100,000 women.6 Overall, 87% of patients diagnosed with anal cancer are non-Hispanic whites, 5% are African American, and 3% are Hispanic.7 The median age at diagnosis is 62 years.7 Thus, the typical American patient with anal cancer is a white woman in her seventh decade of life. In the United States, 5260 new cases of anal cancer (2000 men and 3260 women), were estimated for 2010, with an estimated 720 deaths (280 men and 440 women).1

Epidemiologic studies from Europe and the United States have reported an increased incidence of anal cancer in the past 30 to 40 years. Since 1960, the incidence of anal cancer in Connecticut has doubled in both men and women.6 Between 1974 and 1985, the number of patients in Sweden diagnosed with anal cancer increased 4% per year, an increase similar to that reported for Swedish patients with malignant melanoma.5 Similarly, the number of new cases of anal cancer in Denmark has doubled in men and tripled in women.8

The incidence of anal cancer is higher in urban than in rural populations, and increases in the incidence of anal cancer have been greater in urban than in rural populations.5,6,8 In the United States, the increased incidence of anal cancer has been limited solely to densely populated regions. Young men account for a substantial proportion of this increase. In Denmark, the median age at diagnosis in men has decreased from 68 to 63 years, whereas in women, it has remained constant at 66 to 67 years.8

Association with HIV Infection

At least part of the increased incidence in young men can be explained by the observation that young homosexual men are at increased risk for the development of anal cancer, irrespective of their human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status. An increased risk for anal cancer among never-married men, a surrogate marker for homosexuality,6 has been noted in several epidemiologic studies.9–12 In addition, men with anal cancer are more likely to never have married compared with control subjects who have stomach or colon cancer.6,8 In most areas of the world, anal cancer is more common in women than in men of all age groups.13,14 However, in areas with a relatively high proportion of homosexual men, anal cancer may be more common in men. In San Francisco, for example, the incidence of anal cancer in white men more than doubled from 0.53 per 100,000 in 1975 to 1.2 per 100,000 in 1989,6 and in Los Angeles, anal cancer has become more common in men than in women under age 35.9 A study of Danish homosexual men living in legally registered “marriage-like partnerships” identified an incidence of cancer double what was expected, which could be accounted for by HIV-related cancers, including Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and anal cancer. The relative risk (RR) of anal cancer in this population was 31, and anal cancer appeared to be associated with a positive HIV status.15

The incidence of anal cancer is markedly increased in both men and women who have the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The RR estimated from a linkage analysis of cancer registries and AIDS registries is 63, and it is higher for homosexual men (RR, 84) than for heterosexual men (RR, 38). The increased risk is also apparent during the 5-year period before an AIDS diagnosis. The absolute risk of anal cancer in AIDS patients is 1 per 1000.16

Risk Factors

The pathogenesis of anal cancer is multifactorial. A diagnosis of anal cancer represents the result of an interplay of multiple environmental and host factors. Patients with epidermoid anal cancer are more likely than control patients to have had a previous diagnosis of malignant disease, including cancers of the vulva, vagina, or cervix and lymphoma or leukemia. Patients with anal cancer who are diagnosed before age 60 years are at higher risk of subsequent development of malignant diseases of the respiratory system, bladder, vulva, vagina, and breast, but they are not at increased risk for subsequent development of colon or rectal cancers.17 Overexpression of the c-myc oncogene has been implicated in the pathogenesis of both anal squamous cell neoplasia and breast cancer.18,19 This finding, along with an observed pattern of second malignant diseases and prior malignant diseases in patients with anal cancer, suggests a multifactorial pathogenesis and common oncogenetic risk factors. These factors may include sexually transmitted viruses, environmental carcinogens such as cigarette smoke, immunosuppression, and genetic susceptibility.17

Anal cancer and cancers of the female genital tract share a common pathogenesis.20 In the embryo, the anal and cervical canals are both derived from closely related anlagen.21 Women patients with anal cancer are more likely than women with colon or stomach cancer to have had a prior diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.20 An association between anal cancer and the number of lifetime sexual partners has been reported in women.22 Case-control studies have also found an association between anal cancer and some sexually transmitted diseases.13,22–24 This association, along with the increased incidence in young homosexual men, strongly suggests an etiologic factor for anal cancer associated with increased sexual activity.6

Among sexually transmittable infectious agents, HPV has been the most thoroughly studied potential causative agent. Although there are more than 60 types of HPV, those most commonly associated with benign genital condylomata acuminata are HPVs 6 and 11, whereas HPVs 16, 18, 31, 33, and 35 are associated with malignancy or high-grade dysplasia.25 Several investigators have also reported an association between genital warts and anal cancer in men and women.23–27 The development of anal warts in both sexes has been linked with the practice of anal intercourse.24

The likelihood of finding HPV DNA in specimens of anal cancer varies according to patient demographics and laboratory technique. Patients with HPV-associated anal cancer are 10 years younger on average than patients with reportedly HPV-negative cancers.28 In addition, HPV-associated anal cancer has been reported more frequently in Europe and South America than in South Africa and India.29 When in situ hybridization techniques are used to analyze biopsy specimens of anal cancer, the rate of HPV DNA detection ranges from 17% to 73%.25,28 HPV DNA is more likely to be detected with polymerase chain reaction analysis. Studies comparing both techniques have found that polymerase chain reaction techniques detect HPV DNA in 78% to 85% of patients, whereas in situ hybridization techniques find HPV DNA in only 17% to 50% of the same patients.25,30

Exposure to HPV may be a risk factor even for patients in whom HPV DNA is not detected in the carcinoma specimen. Serum IgA antibodies to a peptide antigen from the E2 region of HPV 16 have been found in 89% of patients with anal cancer compared with only 24% of controls.28 In another study, antibodies to HPV 16 capsids were elevated in 55% of patients with anal cancer compared with 3% of controls. Antibodies to HPV-capsid antigen were detected in an equal number of cancer specimens from patients whose HPV DNA was negative or positive (as assessed by in situ hybridization), which suggests that some presumed HPV-negative patients had been exposed to HPV.31

HPV infection and anal cytologic abnormalities are common in patients with HIV infection.32 HIV-positive patients with HPV DNA found in anal biopsy specimens seem to have a high rate of cytologic abnormalities. In one study of 12 HIV-positive patients without AIDS, 11 patients (92%) with normal cytologic findings but with HPV DNA found in anal mucosa later had cytologic abnormalities at 17-month follow-up.33 Many AIDS patients most likely die of opportunistic infections before anal cancer is manifested. Although the impact of effective antiretroviral therapy on the incidence of anal cancer is not yet clear,34 further increases in the incidence of anal cancer may be observed in AIDS patients as survival time is prolonged.32

Although the true influence of HPV in anal carcinogenesis is uncertain, some laboratory findings point to the involvement of the HPV E6 and E7 proteins. These findings include the observation that the E6 and E7 oncogenes are consistently expressed in tumor cells but that normal E6 and E7 regulatory mechanisms are absent.35 In addition, the E7 protein of HPV 16, in cooperation with the E6 protein, is able to transform mammalian cells in vitro while blocking E6 and E7 gene function, which results in reversal of the malignant phenotype.35–37 Interactions of HPV oncoproteins with known tumor suppressor gene products have been reported. The E6 protein of HPV 16 and HPV 18 forms stable complexes with the p53 protein product of the P53 tumor suppressor gene.38–40 The cellular p53-E6 protein complex results in a lack of appropriate G1 arrest and subsequent genomic instability. The E7 protein also forms complexes with the retinoblastoma gene product and with p107, p130, p33, cdk2, and cyclin A. E7 also activates the cyclin-A promoter and overrides two inhibitory functions that restrict the expression of cyclin A and cyclin E.36

Some evidence suggests that infectious agents other than HPV may contribute to anal carcinogenesis. Associations have been found between the development of anal cancer and a history of syphilis or gonorrhea in men12,23 and between anal cancer and Chlamydia and herpes simplex virus type 2 in both sexes.22,24 In a study of patients in and around San Francisco, herpes simplex virus DNA was detected in 3 of 15 patients with invasive anal cancer and in 3 of 4 patients with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.30 No Epstein-Barr virus or cytomegalovirus DNA was found in the tumor specimens of the 15 patients with anal cancer. Further studies are needed to determine whether these and other sexually transmitted agents are involved in anal oncogenesis or are merely surrogate markers for probable HPV infection.

Chronic immunosuppression is associated with an increased risk for anal malignant disease. Renal transplant recipients have an increased incidence (as high as 100-fold) of carcinoma of the vulva or anus.41,42 These cancers occur at an earlier age than they do in the general population.41 Renal transplant patients also have an increased incidence of cutaneous neoplasia and viral warts. Those with a high susceptibility to cutaneous malignant disease (≥4 skin cancers) are more likely to have HPV DNA-associated skin cancer and are more likely to have an anogenital malignant tumor.43 The increased incidence of anal malignant disease in HIV-positive patients is most likely caused in part by chronic immunosuppression.

A number of authors have reported an association between anal cancer and cigarette smoking.22,24,26,44 When compared with a control group of patients with colon cancer, both men and women smokers were found to have an increased risk of anal cancer.24 In a population-based case-control study of patients with anogenital cancers in the Pacific Northwest, 60% of patients with newly diagnosed anal cancer were current smokers compared with 25% of the controls. The risk of anal cancer was positively correlated with both the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the number of years the patient had been a smoker.44

An association between anal cancer and benign anal conditions (e.g., hemorrhoids, anal fissure, or fistula) has been reported frequently,14,45 and chronic irritation or inflammation of the anal tissue has been assumed to play a role in anal carcinogenesis.26 In a Danish population-based study, patients with anal fissure, fistula, perianal abscess, or hemorrhoids were found to be at increased risk for anal cancer. However, the RR for invasive anal cancer was highest in the year immediately after a diagnosis of benign anal pathology, and it declined from a high of 12 the first year to 1.8 after 5 or more years, suggesting that a so-called benign anal condition is often a symptom rather than a cause of anal cancer.46 Supporting evidence for this view is found in a study of patients treated for benign anal conditions at U.S. Veterans Affairs hospitals. The elevated RR for anal cancer in these patients was most pronounced in the first year after the benign pathologic condition was diagnosed, and it decreased rapidly thereafter until there was no increased risk of anal cancer between year 5 and year 22.47

Prevention and Early Detection

Prevention of anal cancer should include educational efforts about the causal link of sexually transmitted HPV infection with malignant diseases of the anogenital tract. Recommendations of the 1996 National Institutes of Health Consensus Panel on cervical cancer prevention are also applicable to anal cancer and include encouragement to delay onset of sexual intercourse.48 Barrier methods, such as condoms, do not prevent HPV transmission.49 The panel also recommended development of an effective vaccine to prevent transmission of HPV, and a subsequent phase III clinical trial provided encouraging results in this regard.50 Additional preventive efforts should be focused on the treatment of HPV infection, including the development of antiviral agents, targeting of E6 and E7 to block transforming activities, and vaccines to prevent progression of HPV infection.48,51 Education is also required about the causal role of cigarette smoking in anal and other cancers.

Because of the rarity of anal cancer, efforts at early detection through widespread screening are not feasible. However, screening may be feasible in certain high-risk subsets. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia is a common finding in HPV-infected persons.32,33 Analogous to the situation with cervical cancer, where cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions may progress to cervical carcinoma, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) may be a precursor to invasive anal cancer.52–54 Anal cytologic smears have been used to diagnose HSIL in high-risk patients. Because the specificity of anal cytology for the detection of HSIL is low, anoscopy with biopsy is required to differentiate anal condylomata acuminata from HSIL.52 However, the colposcopic criteria to distinguish low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) from cervical HSIL have been used to distinguish LSIL from HSIL of the anus in homosexual and bisexual men.55 This information may allow for a targeted biopsy of suspected HSIL, resulting in increased sensitivity for detection. One study of anal cytology in homosexual and bisexual men reported the sensitivity and specificity for detection of HSIL to be 69% and 59%, respectively, in HIV-positive men and 47% and 92%, respectively, in HIV-negative men.54

Biologic Characteristics

Unlike most gastrointestinal tract malignant diseases, anal cancer is predominantly a locoregional disease, and distant metastasis is relatively rare. Most relapses after curative therapy are located in the pelvis, perineum, or inguinal regions.56 Only 5% to 10% of patients will have cancer that has spread beyond the pelvis at diagnosis,45,57,58 and 10% to 20% of patients will have disease relapse at distant sites after curative local therapy.56,59,60 Although chemotherapy is considered a component of standard therapy for anal cancer, its addition has not decreased the number of patients with distant metastases.58,59,60 As the number of metastatically involved regional nodes increases, so does the risk of distant metastasis.61 The most common site of distant metastasis is the liver, followed, in variable order, by the lungs, extrapelvic lymph nodes*, skin, or bones.

Characteristics of anal cancer that have consistently been correlated with local control and survival are the size and extent of the primary tumor and the status of the inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes. The 5-year survival for patients with tumors 2 cm or more in diameter that are treated surgically is about 80% but declines to 55% to 65% when the tumor is 2 cm to 5 cm or to 40% to 55% when the tumor is more than 5 cm.61,65 The depth of invasion and the size and extent of the primary tumor are prognostic for response to treatment, local control, and survival when patients are treated nonsurgically with radiotherapy and chemotherapy.*

The survival for patients with regional lymph node metastases who are treated primarily with surgical procedures with or without adjuvant therapy is about half that observed in similar patients without nodal metastases.65,69 Similarly, 5-year survival after radiotherapy alone in patients with inguinal lymph node metastases range from 0% to 36% compared with 5-year survival of more than 50% in patients without lymph node involvement.69–71 There is relatively little information in the medical literature about the prognostic significance of regional nodal metastases in patients who receive combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In a retrospective, recursive, partitioning analysis of patients treated at Princess Margaret Hospital, node-positive patients at 5-year follow-up were found to have a trend toward lower cause-specific survival (CSS) (57% vs. 81%; p = .07).59 In the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) randomized trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy and chemotherapy, regional nodal metastases were associated with significantly worse local control (p = .004) and survival (p <.001).72 However, in node-positive patients, the number of involved nodes (≥1), their size (<2 cm or >2 cm), and the extent of involvement (stage N1 or N2 and N3) added no further prognostic information.72

Patient-related variables that have been evaluated as potential prognostic factors for local control and survival in patients with anal cancer include age, gender, race, and performance status. Age probably does not have independent prognostic significance for any endpoint. A retrospective Canadian study found that older patients were treated with less aggressive chemotherapy and were less likely to be offered salvage surgery for recurrence; therefore patients older than 65 years of age were found to be at higher risk for death from anal cancer.73 Conflicting data exist about the impact of gender on prognosis. Several studies have reported no difference in outcome by gender in patients treated with radiotherapy or combined radiotherapy and surgery.59,71,73,74 However, a trend toward higher survival in women has been reported in some surgical series,61,65 and in the EORTC randomized trial, female sex was associated with better survival (p = .12) and local control (p = .05).72 Lower survival has been reported in patients with a lower performance status and in nonwhite patients with anal cancer who received combined-modality therapy.75

Several histopathologic variables have been evaluated as potential prognostic factors in patients with anal cancer. The histologic subtype (squamous cell cancer vs. cloacogenic subtype), tumor cell morphology, extent of differentiation or keratinization, cell size, architecture, and pleomorphism are of no prognostic significance.59,71,73,74,76 The extent of differentiation may be associated with tumor stage because patients with advanced-stage cancer tend to have tumors that are less differentiated.61 The depth of invasion of the primary tumor has been reported to have prognostic significance in patients treated primarily with surgical resection.76 DNA ploidy has also been associated with prognosis in surgically treated patients with DNA aneuploid tumors predictive of an inferior outcome.76 In a Mayo Clinic study of surgically treated patients, those with aneuploid tumors had inferior survival compared with patients with DNA diploid or tetraploid tumors on univariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, however, DNA ploidy was not a significant predictive variable.77

There are currently no clinically useful tumor markers. Despite negative liver imaging, patients with elevated alkaline phosphatase or lactate dehydrogenase are at increased risk for subsequent liver metastases.78 In one study, reduced expression of p21waf1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, was associated with shorter OS.79 Preliminary information suggests that serum antibodies to HPV proteins may eventually be useful as prognostic markers. Elevated serum IgA antibodies to HPV 16 E2 : 9 peptide have been associated with lower survival rates independent of tumor size.28 In another study, patients who died of anal cancer were found to have higher levels of IgG against HPV E7 : 5 peptide than did patients with anal cancer in complete remission or patients who died of other causes.31

Pathology and Pathways Of Spread

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of malignant epithelial tumors of the anal canal includes squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma. Most cases of adenocarcinoma of the anus are actually distal rectal adenocarcinomas with extension into the anal canal. True primary anal canal adenocarcinoma is rare, as is small cell carcinoma of presumed neuroendocrine origin.14,61 Subsets of squamous cell carcinoma in the WHO system include large-cell keratinizing carcinoma, large-cell nonkeratinizing or transitional carcinoma, and basaloid carcinoma.80 Although basaloid carcinomas have historically been considered to be nonkeratinizing tumors, most basaloid carcinomas exhibit keratinization and should be considered squamous cell carcinomas.53

Although most anal canal malignant tumors are squamous cell carcinomas or squamous cell variants, marked morphologic heterogeneity is characteristic.53 Classification of epidermoid anal cancers on the basis of morphologic appearance has led to the use of several potentially confusing terms. These include transitional cell carcinoma, basaloid carcinoma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. These tumors all arise from the anal transition zone and are often grouped together as cloacogenic carcinoma. Mucoepidermoid carcinomas contain mucous microcysts and are histologically dissimilar to mucoepidermoid carcinomas of the salivary glands. The natural history is identical to that of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus without microcysts. Although sometimes considered to be distinct lesions in the medical literature, cloacogenic carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma, basaloid carcinoma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma are all subtypes of squamous cell carcinoma, because patients with these various tumor subtypes have similar clinical characteristics and the tumor subgroups do not differ in natural history or response to therapy.14,45,56,81

Primary anal melanoma is a rare tumor that accounts for only 1% of all anal cancers. Anal melanoma is similar to melanoma of the skin in that it rarely affects African Americans and is characterized by the distant spread of disease.3,82 Outcome is poor after wide local excision or abdominoperineal resection, with just a 10% survival in most series at 5-year follow-up.83

Pathways of Tumor Spread

Anal cancer tumors spread by direct extension to surrounding tissues, lymphatic dissemination to pelvic and inguinal lymph nodes, or hematogenous spread to distant viscera.84 At diagnosis, about half of all anal cancers have been found to invade the anal sphincter or surrounding soft tissue. Although Denonvilliers fascia is usually an effective barrier to prostatic invasion in men, direct extension to the rectovaginal septum is a common occurrence in women.3

The anal canal has several potential lymphatic drainage pathways. The superficial inguinal nodes are the primary drainage basin for that part of the anal canal distal to the dentate line.85,86 Lymphatic drainage around the dentate line occurs to lymphatic plexuses of the rectal mucosa and along the pathway of the inferior and middle hemorrhoidal vessels to obturator and hypogastric lymph nodes. Lymphatic connections also join the anus to presacral, external iliac, and deep inguinal nodes.87

Metastatic involvement of pelvic lymph nodes has been reported in 25% to 35% of patients treated primarily with abdominoperineal resection.45,61 Inguinal node metastases are found in about 10% of patients at diagnosis; the risk depends on the size and extent of the primary tumor.56,57 The incidence of inguinal node metastases may be as high as 20% for tumors more than 4 cm in diameter and as high as 60% when there is direct invasion of adjacent pelvic organs.57 Recurrence in undissected inguinal nodes has been reported in 13% of surgically managed patients with clinically negative inguinal lymph nodes.61

Clinical Manifestations, Patient Evaluation, and Staging

Rectal bleeding is the most common symptom of anal malignant disease. Perineal pain, mass sensation at the anus, and a change in bowel habits are also frequently reported.14,45,88–91 Many patients with symptoms of early anal cancer are diagnosed initially with a benign anal condition, such as hemorrhoids, anal fissures, or fistulae.14,45

Most patients with anal cancer are diagnosed at an early stage. A national survey of such patients found that 73% were diagnosed with stage 0 to II cancer, whereas only 8% were diagnosed with stage IV cancer.7 The interval from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis may be quite prolonged, however, exceeding 1 month in 80% of patients and 6 months in 33%. A study of Norwegian patients with anal cancer found that nearly one third of them had a delay of more than 6 months from onset of symptoms to diagnosis.91 This finding emphasizes the importance of a thorough digital rectal examination in patients with anal symptoms.46,47,91

Patient Evaluation

In addition to a complete general physical examination, a detailed examination should be conducted of the abdomen, inguinal region, anus, and rectum. The extent of circumferential involvement of the anal canal should be noted, and documentation should be made of the size, extent, and location of the primary tumor. The size, location, and mobility of palpable inguinal lymph nodes should be noted. Pararectal lymph nodes may be involved metastatically, but these are rarely palpable by digital rectal examination.71

Laboratory studies should include a complete blood cell count, measurement of serum creatinine levels, and liver function studies of bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase, and glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase. For patients with HIV risk factors, a determination of HIV status should be made before the initiation of therapy. Although concentrations of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) are elevated in 20% of patients with anal cancer, post-treatment CEA values have not been found to correlate with clinical outcomes and have not proven useful in patient management.92 There are no other clinically useful tumor markers for anal cancer.

Radiographic evaluation should include chest radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen and pelvis. The CT scan is generally inferior to the physical examination for the characterization of primary tumors, but it is useful for the evaluation of the liver and the perirectal, inguinal, pelvic, and para-aortic lymph nodes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has not yet been proven to be more clinically useful than CT scanning. The depth of invasion of the primary tumor may be evaluated with ultrasonography.93

PET imaging is useful in further evaluating the extent of the primary tumor and the presence of regional lymph node metastases, and distant metastases, as well as in evaluating the response to therapy.94–96 A retrospective evaluation of the sensitivity of PET/CT imaging compared with physical examination and CT scanning alone among 41 patients with anal cancer showed that PET/CT imaging detected the primary tumor in 91% of patients compared with only 59% by CT scanning alone.97 In addition, PET/CT identified positive inguinal nodes in 17% of patients who were found to be clinically negative by CT and physical examination. Another series reports that use of PET during initial staging led to a change in stage in 23% of patients and radiotherapy field changes in 13% of patients.98 Furthermore, a post-therapy PET scan showing resolution of metabolic activity was reported to be highly associated with improved progression-free survival (PFS) (95% at 2 years vs. 22%; p <.0001).99

Staging

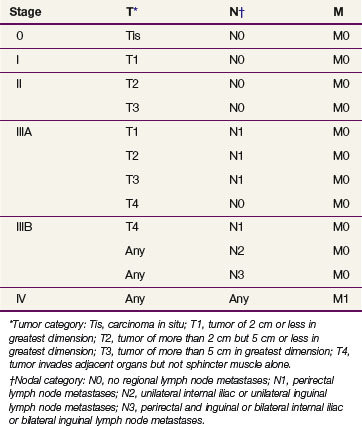

Anal cancer should be staged according to the TNM staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)100 (Table 50-1). Tumors are classified according to their maximum diameter and their invasion of adjacent structures, as determined by the physical examination and any imaging studies. ![]()

In earlier editions of the staging system of the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (International Union Against Cancer [UICC]),71 primary tumors were classified not by size but rather according to the length and extent of their circumferential involvement with the anal canal. Tumors involving less than one third of the length and circumference of the anal canal were classified as T1 category of disease, whereas those that involved more than one third of the length or circumference or that invaded the external sphincter were classified as T2. As in the current system, T3 tumors involved the rectum or perianal skin, and T4 tumors invaded adjacent structures.

The AJCC staging system for anal canal cancer is applicable to all carcinomas that arise from the anal canal. Cancers of the anal margin (distal to the anal verge) are staged as skin cancers, but melanoma of the anal canal is excluded. For staging purposes, the regional lymph nodes in the AJCC system are the anorectal, perirectal, lateral sacral, internal iliac (hypogastric), and superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes.100

Primary Therapy

Surgery Alone

Before the establishment in the 1980s of sphincter-sparing therapy as the standard of care for epidermoid anal cancer, most patients with anal cancer in North America were treated surgically with abdominoperineal resection. Reported 5-year OS after abdominoperineal resection for anal cancer ranged from 25% to 70% (average, 50%).61,65,101 Locoregional recurrence developed in 25% to 35% of patients and distant metastasis in 10%.61,65,101 Patients at highest risk for local recurrence (range, 36% to 48%) after abdominoperineal resection are those with extension of the primary tumor beyond the anal sphincter or metastases to inguinal or pelvic lymph nodes.61 A component of locoregional disease is present in as many as 84% of patients with relapse after abdominoperineal resection.61 When the inguinal lymph nodes are metastatically involved, 5-year OS after primary surgical therapy is only 10% to 20%.101 Although abdominoperineal resection is now rarely used initially, it is still useful for treatment of patients with local recurrence after conservative therapy and for management of complications after conservative therapy.101

Irradiation Alone or Plus Chemotherapy

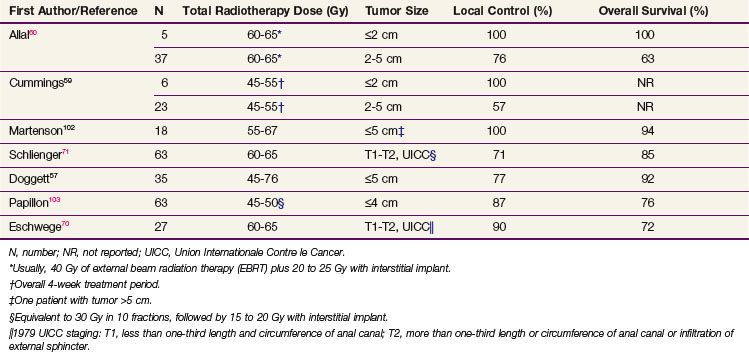

High-dose radiotherapy without surgical resection or other adjuvant therapy is an effective treatment for small stage T1 tumors without inguinal adenopathy. Table 50-2 summarizes the local control and survival results from retrospective series of radiotherapy alone for small anal cancers. For patients with anal cancers of 2 cm or less in diameter, 100% local control 5 years after radiotherapy without chemotherapy has been reported in several small series of less than 10 patients each.59,60,102 Local control rates at 5 years are lower (57% to 76%) in patients with 2- to 5-cm tumors.59,60,103

Radiation Alone or Plus 5-FU and Mitomycin C

The only prospective randomized trial to compare radiotherapy alone with the combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in patients with node-negative anal cancers 5 cm or less in diameter (T1 to T2, N0) was carried out by the United Kingdom Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research (UKCCCR) Anal Cancer Trial Working Party.104 In this trial, 223 of 585 patients had T1 or T2, N0 anal cancer and were randomized to receive 40 to 45 Gy of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to the pelvis, followed by a 15- to 25-Gy boost with a perineal field or interstitial implant with or without two 4- or 5-day infusions of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and a single bolus injection of mitomycin C. Using local control as the endpoint, subset analysis showed a statistically significant advantage for combined-modality therapy for patients with T1N0 or T2N0 anal cancer.105

Combined-modality therapy with radiotherapy and chemotherapy is appropriate for most patients with anal cancer and has become the standard of care. Statistics from the U.S. National Cancer Data Base for 1988 and 1993 show that the use of chemotherapy has increased but the use of resection as the primary treatment has declined.7

The initial studies that led to the adoption of combined-modality therapy with nonsurgical treatment were conducted at Wayne State University. Before scheduled surgical resection, 30 Gy of radiation in 15 fractions was delivered to the true pelvis, medial inguinal nodes, and anal canal in conjunction with concomitant 5-FU 1000 mg/m2 every 24 hours for 4 days as a continuous infusion and mitomycin C in a single bolus injection of 15 mg/m2. After five of the first six patients were found to have no residual tumor in the abdominoperineal resection specimen 4 to 6 weeks after the completion of radiotherapy, surgical resection was subsequently reserved for locally persistent or recurrent disease after radiotherapy and chemotherapy.64 Overall, 86% of patients (24 of 28) had a clinical complete response to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and 7 (58%) of the 12 patients who had an abdominoperineal resection had a complete pathologic response.106

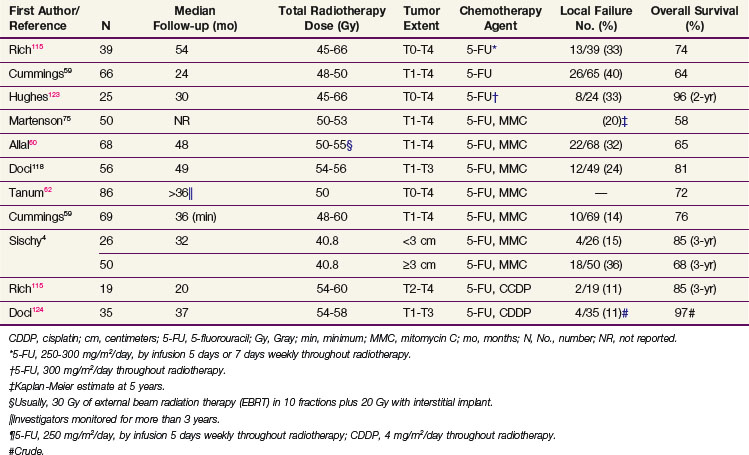

Table 50-3 summarizes the disease control and survival results with concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy from several series. Local failure after radiation doses of 45 to 60 Gy with concomitant chemotherapy occurred in 11% to 40% of patients, and 5-year actuarial survival rates were 65% to 80%.

TABLE 50-3 Disease Control and Survival Rates after Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy for Anal Cancer in Selected Series

Two randomized studies comparing radiotherapy alone with concomitant radiotherapy and 5-FU and mitomycin C chemotherapy have been performed by the EORTC72 and the UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party.104 For patient eligibility, the EORTC trial required a locally advanced primary tumor (stage T3 or T4) or involvement of regional lymph nodes, whereas the UKCCCR trial enrolled patients with any stage of disease, including distant metastases. Initial radiotherapy was similar in both trials and consisted of 45 Gy to the pelvis over 4 to 5 weeks. In the EORTC trial, partial responders at 6 weeks after induction therapy were boosted with an additional 20 Gy and complete responders received 15 Gy. In the UKCCCR trial, a 15- to 25-Gy boost was administered to patients with more than a 50% tumor response; patients with less than a 50% response had radical surgery. Chemotherapy in the EORTC trial consisted of 5-FU 750 mg/m2 every 24 hours on days 1 to 5 and days 29 to 33 with a single 15-mg/m2 dose of mitomycin C on day 1. Chemotherapy in the UKCCCR trial consisted of 5-FU 1000 mg/m2 every 24 hours on days 1 to 4 and days 29 to 32 or 750 mg/m2 every 24 hours on days 1 to 5 and days 29 to 33, with a single mitomycin C dose of 12 mg/m2 given on the first day of radiotherapy.

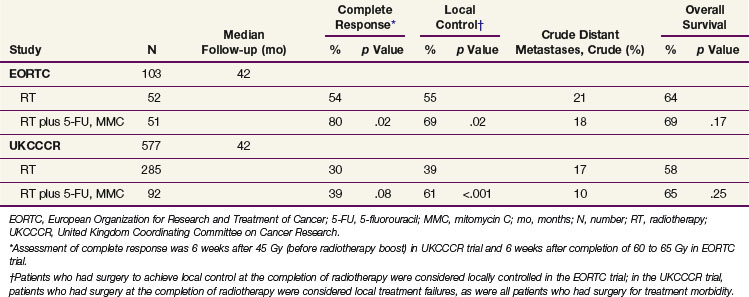

Results of the EORTC72 and UKCCCR104 trials are summarized in Table 50-4. The complete response rate 6 weeks after boost radiotherapy was significantly improved with the addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy (80% vs. 54%; p = .02) in the EORTC trial. A nonstatistically significant trend toward a higher complete response rate was also reported in the UKCCCR trial. However, this endpoint was measured 6 weeks after the initiation of therapy compared with 6 weeks after the completion of all therapy in the EORTC trial. In both studies, local control was significantly improved with the addition of chemotherapy. Local control with radiotherapy alone was surprisingly low (39% at 3 years) in the UKCCCR study. The definition of local failure included tumor reduction of less than 50% 6 weeks after 45 Gy of irradiation, surgery for morbidity, and failure to close a pretreatment colostomy for any reason. Conversely, EORTC investigators considered patients locally controlled even if they had to undergo surgery to achieve a complete response at the completion of radiotherapy. Neither study reported any significant impact of chemotherapy on the incidence of distant metastases or on OS, although absolute survival at 3 years slightly favored the chemoradiation arms numerically in both trials.

TABLE 50-4 3-Year Disease Control and Survival in Randomized Studies Comparing Radiotherapy Alone with Radiation and Chemotherapy

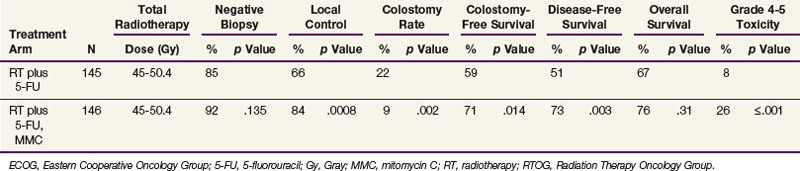

The EORTC and UKCCCR trials established combined-modality therapy as the standard of care for patients with anal cancer. Further refinement in the understanding of optimal therapy is provided by the results of a phase III study conducted by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG). In the RTOG/ECOG study (Table 50-5), patients were treated with radiotherapy (45 to 50.4 Gy in 25 to 28 fractions) and 5-FU and were randomized to receive or not receive mitomycin C.107 The addition of mitomycin C was associated with fewer colostomies, higher local control, and better disease-free survival (DFS). The addition of mitomycin C also significantly increased the risk of major toxicity. Survival was slightly higher in the mitomycin C arm of the study, but the difference was not statistically significant. The chemotherapy regimen in this trial differed from that of the European trials because two doses of mitomycin C 10 mg/m2 were delivered on day 1 and day 29 instead of a single dose. Two of the four treatment-related deaths in the mitomycin C arm were believed to be caused by a failure to follow protocol dose-reduction guidelines for the second mitomycin C dose.

TABLE 50-5 4-Year Disease Control, Survival, and Toxicity after Radiotherapy and 5-FU Alone or Plus Mitomycin C: Results of RTOG/ECOG Randomized Trial 1289104

The biologic basis for improved outcome with the addition of chemotherapy to the treatment regimen is not known. However, the fact that several studies have reported no significant reduction in distant failure with chemotherapy suggests that the effect is predominantly locoregional, possibly because of an interaction with irradiation.59 For example, in the Princess Margaret Hospital experience, distant failure occurred in 18% of patients treated with radiotherapy alone, in 17% of those who received mitomycin C and 5-FU, and in 10% of those receiving 5-FU alone.59,108 Synergistic interactions between irradiation and 5-FU or mitomycin C and between 5-FU and mitomycin C have been demonstrated in mammalian tumor cell lines in vitro.109 Hypoxic mammalian tumor cells also have an increased sensitivity to mitomycin C in vitro, although whether the hypoxia has any effect when anal cancer is treated with fractionated radiotherapy is not known.110 Laboratory studies have also shown increased cytotoxicity associated with continuous infusion 5-FU compared with 5-FU delivery by intermittent bolus.111

It cannot be assumed that sequential therapy will duplicate the excellent results achieved with concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Complete pathologic response rates 6 weeks after 50 Gy of irradiation, 5-FU, and mitomycin C are in the range of 85% to 95%.70,112,113,114 In contrast, only 45% of 42 patients who received sequential 5-FU and mitomycin C, followed by radiotherapy, had a complete pathologic response.89

Radiation Plus 5-FU and Mitomycin C versus 5-FU and Cisplatin

In addition to the concurrent use of mitomycin C and 5-FU during radiotherapy, multiple single institutions115,116–118 and prospective phase II trials119–121 have reported favorable results with concurrent cisplatin and 5-FU, with or without an induction chemotherapy phase of treatment. A U.S. Gastrointestinal Intergroup phase III trial (RTOG 9811) was conducted to compare the efficacy of concurrent cisplatin-based therapy with standard mitomycin C–based therapy.122 Six hundred forty-four patients with stage T2 or higher (any stage N) carcinoma of the anal canal were randomized to two cycles of induction cisplatin (75 mg/m2) and 5-FU (1000 mg/m2 for 4 days) followed by 45 to 59 Gy of irradiation with two concurrent cycles of the same regimen versus mitomycin C (10 mg/m2) and 5-FU (1000 mg/m2 for 4 days) given twice concurrently during radiotherapy (no induction phase). For the cisplatin- and mitomycin C–based arms, 5-year OS was 70% and 75%, respectively (p = .10), and 5-year DFS was 54% and 60%, respectively (p = .17). There was a significant difference in 5-year colostomy rates favoring the mitomycin C arm (10% vs. 19%; p = .02). Based on this trial, a regimen of mitomycin C and 5-FU given concurrently with radiotherapy remains the standard of care for anal cancer. It is unclear whether the delayed use of radiotherapy or difference in radiosensitization of cisplatin compared with mitomycin C played a role in the inferior colostomy rate observed in the experimental arm of this study.

Treatment Tolerance

Anal function is preserved in 65% to 80% of patients after sphincter-sparing therapy.59,60,74,123 The most common indication for abdominoperineal resection is local recurrence or disease persistence, because 90% of patients for whom local control is achieved can be expected to maintain a functional anus.58 Late treatment complications may result in the loss of anal function, and a colostomy may be required to manage complications in 2% to 10% of patients whose cancer is locally controlled.*

Locally Advanced Disease and Palliation

Tumor size appears to have a moderate impact on treatment outcome when combined-modality therapy is used. In the RTOG/ECOG study, 17% of patients with primary tumors 5 cm or more in diameter had positive biopsy findings 6 weeks after completion of therapy compared with 7% of those with a tumor less than 5 cm in diameter (p = .02). Preservation of anal function was also more likely in patients who had smaller tumors; 11% of patients with T1 or T2 cancer required a colostomy compared with 21% of those with T3 or T4 cancer.107 Differences in local control have also been reported using tumor diameter cutoffs of less than 5 cm. In an earlier RTOG study, local control at 3 years was 84% among patients with tumors smaller than 3 cm and 62% among those with tumors 3 cm or larger.4 Similarly, local control among patients treated at Princess Margaret Hospital was 94% for those with tumors of 2 cm or less and 72% for those with larger tumors. No difference in local control was reported between the subgroups of patients with tumors of 2 cm to 5 cm or with larger tumors (>5 cm), unless invasion of adjacent structures was discovered, in which case local control was 62%.59

Secondary analyses of the U.S. Gastrointestinal Intergroup RTOG 9811 phase III trial, the largest prospective database of anal cancer patients, have been performed to further define prognostic factors for outcomes in patients treated with concurrent chemoradiation. The initial analysis found that a tumor size of more than 5 cm was the only pretreatment characteristic that independently predicted a subsequent need for colostomy (hazard ratio, 1.85; p = .008).126

A subsequent analysis of RTOG 98-11 was performed to determine if the TN category of disease (T2N0, T3N0, T4N0, T2N+, T3N+, T4N+) has an impact on disease-free (DFS) and OS, locoregional relapse, distant metastasis, and/or colostomy failure (CF).127 All endpoints showed statistically significant differences between the TN categories of disease, including OS (p = .0001), DFS (p <.0001), locoregional failure (p <.0001), distant metastasis (p = .0035), and CF (p = .0147). The best outcomes for OS, DFS, and locoregional relapse were found with T2N0 and T3N0 categories of disease (5-year OS, 81% and 75%; DFS, 69% and 63%; and locoregional relapse, 19% and 22%). The poorest outcomes were with the T3N+ and T4N+ disease categories (5-year OS, 44% and 48%; DFS, 26% and 34%; and locoregional failure, 58% and 64%). Patients with T4N0 and T2N+ disease had similar outcomes (5-year OS, 59% and 66%; DFS, 40% and 40%; and locoregional failure, 50% and 40%). The colostomy failure at 3 years was best for patients with T2N0 (10%) or T2N+ (9%) disease and worst for patients with T4N0 (28%) and T3N+ (23%) disease.

Preservation of anal function is possible in most patients with locally advanced disease. In the Princess Margaret Hospital experience, two thirds of patients with tumors that invaded adjacent structures maintained anal function after radiotherapy and chemotherapy, as did two thirds of patients with tumors that involved more than 75% of the circumference of the anal canal.59 Locally advanced disease is not an indication for abdominoperineal resection in patients who retain some measure of anal function at diagnosis.59

Node Involvement

Involvement of the inguinal lymph nodes at diagnosis is associated with a worse prognosis. In the EORTC randomized trial, patients with involved lymph nodes had inferior local control and survival. However, the extent of nodal involvement did not add any prognostic information.72 In a report from Princess Margaret Hospital, the 5-year cause-specific survival for clinically node-positive patients was 57% compared with 81% for node-negative patients (p = .07). Combined-modality therapy was effective in the treatment of patients with involved nodes. In such patients, control of cancer in metastatically involved lymph nodes was achieved 87% of the time.59 In an RTOG 9811 secondary analysis, 5-year DFS was 64% for node-negative patients and only 35% for node-positive patients (p ≤.0001).126 As noted in the prior section, in a subsequent secondary analysis of RTOG 98-11, the poorest rates of OS, DFS, and locoregional relapse were with T3 to 4, N+ disease; patients with stage T2N+ lesions had similar outcomes to those with T4N0 disease.127

Radiotherapy without chemotherapy has been used for patients with metastatically involved inguinal lymph nodes, with control of nodal disease reported in 60% to 70% of patients.57,74 However, survival is poor for these patients with radiotherapy alone (range, 0% to 36% at 5 years), and combined-modality therapy with radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy is preferred.69–7174

Salvage Therapy

Patients with local failure after radiotherapy and chemotherapy should be considered for abdominoperineal resection. Local control can be achieved with abdominoperineal resection in as many as 60% of these patients.* Ultimate local control is obtained in more than 90% of patients with anal cancer, including patients who require surgery after radiotherapy for locally persistent or recurrent disease.57,74

Palliation

Although anal cancer is predominantly a locoregional disease, 5% to 10% of patients will have disease beyond the pelvis at diagnosis and distant metastases will develop in 10% to 20% after locoregional therapy.58,59,60 The most common site of distant metastases reported in most series is the liver; metastases to the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, bones, and brain have also been reported.† Palliative chemotherapy with 5-FU plus either mitomycin C or cisplatin is associated with a 50% response rate and a median survival of 12 months.58 Patients with brain metastases, symptomatic osseous metastases, or other localized symptomatic metastases should receive hypofractionated radiotherapy for palliation.

Irradiation Techniques and Tolerance

Traditional Field Design

Radiotherapy field design should be based on an understanding of the spread of anal cancer. Historical results in patients treated by abdominoperineal resection show that 35% to 46% had involvement of pelvic lymph nodes and that 13% to 16% had a recurrence in the inguinal lymph nodes.61,65 Therefore, the pelvic and inguinal lymph nodes should be included in the radiotherapy fields.

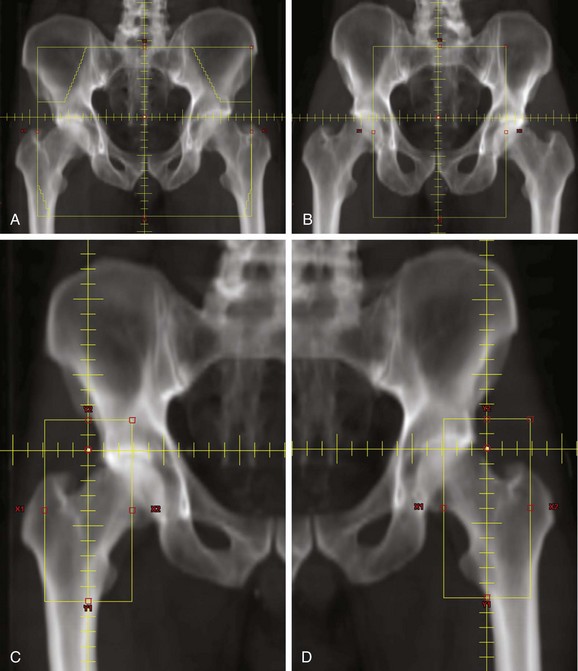

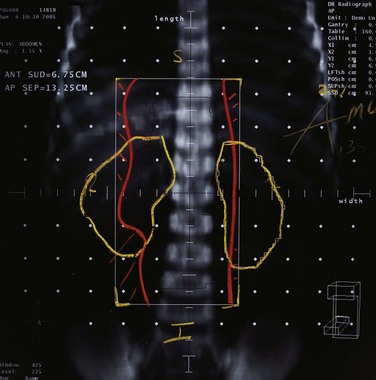

A portion of the inguinal lymph node chain is superficial to the femoral head and neck. It is important to use radiotherapy fields that decrease the radiation dose to these structures. Large AP/PA (anteroposterior, posteroanterior) fields that include the inguinal lymph nodes will deliver the full radiation dose to the femoral head and neck. Patients treated in this way may be at risk for radiation-induced fracture.102 Radiotherapy techniques that treat the lateral inguinal lymph nodes only through anterior fields will minimize the dose to the femoral head and neck. One method is to treat the primary tumor, pelvic nodes, and inguinal nodes with an anterior photon field that encompasses all these structures. The posterior field is designed to treat only the primary tumor and the pelvic lymph nodes. Electron fields are used to supplement the dose to the lateral superficial inguinal nodes that are not included in the posterior photon field (Fig. 50-1). Another technique is to use CT-based simulation for optimal delineation of the inguinal lymph nodes and then to use this information to minimize the volume of the femur included within the radiotherapy field.

Target Volumes and Normal Structures

A retrospective review of 167 patients treated at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center with definitive chemoradiation reported that all regional pelvic failures (21% of recurrences) occurred among patients whose superior field border was placed at the bottom of the sacroiliac joint. The authors concluded that a superior field or target border at vertebrae L5/S1 may reduce such recurrences.128

In 2009, an RTOG panel reported consensus contouring guidelines and an atlas for elective CTV demarcation in anorectal cancer.129 This reference serves as an excellent template and resource for lower gastrointestinal cancer treatment planning. Key normal structures that should be identified in the planning process and avoided include the femoral head and neck, bladder, and bowel. Excessive skin exposure should also be avoided in the perineum and groin.

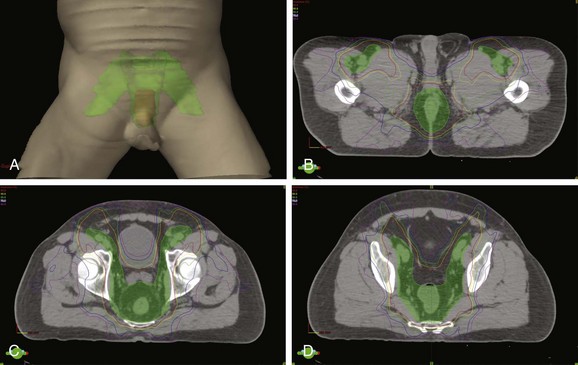

Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy

Given the close proximity of the bladder, small bowel, femoral heads, and possibly pelvic bone marrow to target regions in the management of anal cancer, the improved conformality of IMRT compared with traditional techniques presents an opportunity for toxicity reduction130,131 (Fig. 50-2). A retrospective review of 53 patients treated at multiple institutions has reported favorable acute toxicity and efficacy rates with early follow-up among 53 patients treated with IMRT and concurrent chemotherapy.132 Over 92% of patients had a complete clinical response, and acute grade 3 or higher gastrointestinal or dermatologic toxicities were observed in only 15% and 38% of patients, respectively. A preliminary report of RTOG 0529, a phase II trial of 51 patients treated with IMRT and concurrent mitomycin C and 5-FU also shows favorable patient tolerance rates.133 Compared with the historical benchmarks of RTOG 9811, there was less grade 3 or greater gastrointestinal or genitourinary toxicity (22% vs. 36%; p = .014) and dermatologic toxicity (20% vs. 47%; p = .0001), with a favorable early clinical response reported. Further reports of institutional experiences and prospective clinical trials with IMRT will continue to define the benefit and proper implementation of these technologies in the management of anal cancer.

Radiation Dose and Fractionation

The RTOG/ECOG randomized clinical trial has provided useful information about the most favorable combination of radiation dose and chemotherapy agents.107 The best local control rates resulted from an aggressive regimen of concurrent chemoradiation (5-FU, 1000 mg/m2/day on days 1 to 4 and days 29 to 32 of EBRT; mitomycin C, 10 mg/m2 on day 1 and day 29 of EBRT). The primary tumor, pelvic lymph nodes, and inguinal lymph nodes received a total dose of 36 Gy of EBRT in 20 fractions, followed by a field reduction to include the primary tumor. An additional 9 Gy was administered in 5 fractions, for a total dose to the primary tumor of 45 Gy in 25 fractions. Patients who had residual tumor after 45 Gy received an additional dose of 5.4 Gy in 3 fractions, for a total cumulative primary tumor dose of 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions. The medial inguinal lymph nodes received 45 Gy if clinically negative or 50.4 Gy if clinically positive. This combination of radiotherapy plus 5-FU and mitomycin C resulted in 4-year local control of 84%, which was significantly better than 4-year local control of 66% in patients randomized to receive an identical dose of irradiation plus 5-FU alone (p <.001).

The hypothesis that there will be fewer local failures when the irradiation dose is increased to more than 50.4 Gy with concurrent 5-FU and mitomycin C has not been tested in prospective trials. Three retrospective series have contributed to the formation of this hypothesis. At the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, patients with anal cancer who were treated with radiotherapy and continuous infusion 5-FU 300 mg/m2 during the entire radiotherapy course had better local control with radiation doses of 55 to 66 Gy (9 of 10 patients) than with lower doses of 45 to 49 Gy (7 of 14 patients).123 Researchers at the University of Kansas evaluated treatment with or without chemotherapy and found local control of 92% for radiation doses of more than 55 Gy, 77% for 45 to 55 Gy, and 64% for 45 Gy or less.134 Similarly, a retrospective review from the Medical University of Vienna demonstrated 14% local recurrence with doses of 54 Gy or more compared with 70% with doses of less than 54 Gy among patients with T3 or T4 tumors.135

In contrast to dose escalation for locally advanced tumors, more moderate doses of irradiation with chemotherapy may be adequate for very early tumors or after local excision of a small tumor. In addition to the original experience with complete responses to 30 Gy reported by Nigro and colleagues,106 at least two other institutions have reported local control of over 95% with 30 Gy and concurrent chemotherapy among a limited number of patients with early tumors or after local excision.136,137 Such a strategy has not been evaluated in a prospective clinical trial.

EBRT alone is appropriate for a few patients who are not candidates for combined-modality therapy because of clinically significant comorbid illness or other reasons. A high rate of tumor control has been found in patients with small tumors treated with a radiation dose of 45 Gy in 25 fractions to the pelvis, inguinal lymph nodes, and primary tumor, followed by a boost dose to the primary tumor, for a total cumulative dose of 60 to 63 Gy in 33 to 35 fractions.70,102

Nearly all patients who receive concomitant chemoirradiation for anal cancer will have perineal skin reactions, and more than half will have confluent moist desquamation. The severity of such acute reactions is influenced by the radiation fraction size. In a Princess Margaret Hospital study of 50 Gy in 20 fractions (2.5 Gy per fraction), the acute and late toxicities were considered unacceptably high.59 Less severe toxicity was reported with the same fractionation schedule and a break in treatment or with a fractionation schedule of 48 Gy in 24 fractions.59

The overall treatment time may affect the outcome of radiotherapy. In an RTOG pilot study evaluating 59.4 Gy with 5-FU and mitomycin C that included a planned treatment break, 30% of patients required a colostomy by year 2 compared with only 7% in the RTOG/ECOG randomized trial, which did not use planned treatment breaks.138,139 Pooled data analysis of RTOG 8704 and 9811 determined that each increase in treatment duration by 14 days was associated with a 9.4% increase in risk of failure requiring colostomy.140

Tumor Regression

Tumor regression may be slow after radiation therapy alone or chemoradiation, with the time to complete regression ranging from 2 to 36 weeks (median, 12 weeks).59 Most recurrences at the primary site manifest within 2 years of treatment.59 When concurrent chemotherapy is not used, tumor regression may be even more prolonged. In a French study of 193 patients with anal cancer treated with radiation therapy alone, the mean time to a complete response was 3 months after the completion of therapy, and some patients required as long as 12 months for a complete response.71 However, the rapidity of the clinical response to therapy may also be prognostic. Another institution from France reported that patients with T3 to T4 tumors who had a tumor reduction of 80% or less at the completion of the first phase of radiotherapy (30 to 45 Gy of EBRT) had 5-year colostomy-free survival of only 24.8% compared with 65% among patients with a response of more than 80% (p = .002).141

Although routine biopsies have been required 4 to 6 weeks after the completion of therapy in several studies,64,75,89 routine biopsies should not be performed on patients with regressing or clinically absent tumors. Treatment with 30 to 50 Gy plus 5-FU and mitomycin C is associated with negative biopsy findings in 85% to 90% of patients 4 to 6 weeks after completion of radiotherapy.64,112,113 Because of accelerated repopulation in surviving clonogens, a low-dose radiation boost after a 6-week break is unlikely to provide any benefit. The purported benefit of additional therapy for 7 of 22 patients in the RTOG/ECOG study is more likely a result of continued slow tumor regression after initial therapy than the result of the addition of 9 Gy of irradiation and cisplatin chemotherapy.

Treatment Tolerance

The acute toxicity associated with therapy for anal cancer may depend in part on the radiation fraction size and schedule and how chemotherapy is used. Investigators at Princess Margaret Hospital reported a decrease from 75% to 40% in acute grade 3 toxicities when the fraction size was reduced from 2.5 to 2 Gy or when a planned treatment break was used.59 Acute toxicity is markedly higher when mitomycin C is added to 5-FU and radiotherapy. In the RTOG/ECOG trial, 26% of patients who received 5-FU and mitomycin C together experienced grade 4 or grade 5 toxicity (3% treatment-related deaths), compared with only 7% of patients receiving 5-FU (0.7% treatment-related deaths).114 As noted previously, IMRT appears to decrease the incidence of grade 3 or higher treatment intolerance.

For patients receiving both mitomycin C and 5-FU, the most common life-threatening toxicity is bone marrow suppression resulting in neutropenic sepsis. In addition, essentially all patients will experience a perineal skin reaction.4 In the RTOG/ECOG study, confluent moist desquamation was reported in 55% of patients treated with this combination.139 Mild to moderate diarrhea may be experienced by two thirds of patients, and nausea and vomiting by 25% and 15%, respectively.4

Late treatment-related complications are usually diagnosed within 2 years of treatment.70 Asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic perineal fibrosis, telangiectasia, and minor intermittent bleeding from the anorectal region or bladder may be observed.142 Severe late effects that affect a patient’s social life or require surgical intervention have been reported in as many as 15% of patients.59,62,70 These effects include anal incontinence, intestinal obstruction, chronic diarrhea, chronic pelvic pain, fistula, or bladder dysfunction.62 Elderly women may be at increased risk for fractures of the femoral head and neck, especially if the radiotherapy fields encompass the entire femoral head and neck in both anterior and posterior treatment fields.95 Late complications may necessitate colostomy for management in 2% to 10% of patients.* Whether the use of IMRT will reduce late toxicity remains to be seen.

Late complications of radiotherapy may be more likely when treatment is delivered with fraction sizes larger than 2 Gy.59 Late complications are also more common in patients with locally advanced tumors; one series reported late effects in 23% of patients with T3 or T4 tumors compared with only 6% of patients with T1 or T2 tumors.70

Some investigators have reported that HIV-positive patients with anal cancer have reduced tolerance for combined chemoradiation regimens.143,144 Compared with HIV-negative patients, HIV-positive patients are more likely to require treatment breaks, hospitalization for acute reactions, and chemotherapy dose reductions.144,145 In addition, survival of HIV patients is often limited; one report found a 29% 2-year survival for HIV-positive patients compared with 71% at 4 years for HIV-negative patients.144 Although the best treatment strategy is unknown, low-dose chemoradiation in a small series of patients has been reported to result in a satisfactory tolerance and response in HIV-positive patients and in patients with AIDS without major opportunistic infections.145

The advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the management of HIV-positive patients appears to have led to improved tolerance and treatment outcomes among HIV-positive patients. A pooled retrospective analysis from four institutions of 121 patients with anal cancer treated in the HAART era revealed similar clinical complete response rates (≥92%) and OS among HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients.146 However, HIV-positive patients were much more likely to fail locally by 5 years (62% vs. 13%; p = .008) and had increased dermatologic and hematologic acute toxicity with therapy. Other institutions have reported successful treatment and acceptable toxicity with standard anal cancer chemoradiotherapy regimens among HIV-positive patients in the HAART era,147–151 but some have also noted inferior long-term local control rates despite excellent initial response rates.152

Treatment Algorithm and Future Directions

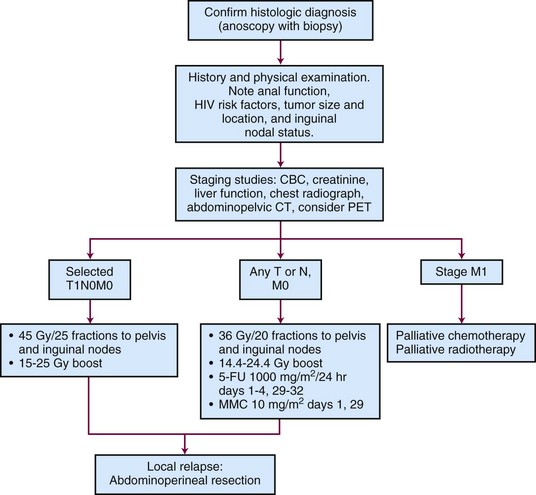

Figure 50-3 is a diagnostic and treatment algorithm for patients with newly diagnosed anal cancer.

Though RTOG 9811 demonstrated a reduction in severe acute hematologic toxicity with the experimental cisplatin-based arm, there is an opportunity for study of newer cytotoxic, radiosensitizing agents in an attempt to improve efficacy or reduce chemotherapy-related side effects. In addition, the incorporation of biologic agents, such as epidermal growth factor inhibitors (e.g., cetuximab), with treatment has the potential to improve efficacy, as has been demonstrated in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.153 The potential benefit of adjuvant systemic chemotherapy, especially among patients with advanced nodal disease, has also not been defined by clinical trial.

A long-term update of U.S. GI Intergroup RTOG 98-11 has shown that concurrent chemoradiation with 5-FU plus mitomycin has statistically better 5-year DFS and OS than induction plus concurrent 5-FU/cisplatin and remains the preferred standard of care (5-year DFS, 67.7% vs 57%, p = .0044; 5-year OS, 78.2% vs 70.5%, p = .021).154

4 Sischy B, Doggett RL, Krall JM, et al. Definitive irradiation and chemotherapy for radiosensitization in management of anal carcinoma. Interim report on Radiation Therapy Oncology Group study no. 8314. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(11):850-856.

51 Franceschi S, De Vuyst H. Human papillomavirus vaccines and anal carcinoma. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(1):57-63.

57 Doggett SW, Green JP, Cantril ST. Efficacy of radiation therapy alone for limited squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15(5):1069-1072.

59 Cummings BJ, Keane TJ, O’Sullivan B, et al. Epidermoid anal cancer: treatment by radiation alone or by radiation and 5-fluorouracil with and without mitomycin C. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(5):1115-1125.

61 Boman BM, Moertel CG, O’Connell MJ, et al. Carcinoma of the anal canal. A clinical and pathologic study of 188 cases. Cancer. 1984;54(1):114-125.

64 Leichman L, Nigro N, Vaitkevicius VK, et al. Cancer of the anal canal. Model for preoperative adjuvant combined modality therapy. Am J Med. 1985;78(2):211-215.

68 Longo WE, Vernava AM3rd, Wade TP, et al. Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Predictors of initial treatment failure and results of salvage therapy. Ann Surg. 1994;220(1):40-49.

72 Bartelink H, Roelofsen F, Eschwege F, et al. Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer. Results of a phase III randomized trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiotherapy and Gastrointestinal Cooperative Groups. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(5):2040-2049.

75 Martenson JA, Lipsitz SR, Lefkopoulou M, et al. Results of combined modality therapy for patients with anal cancer (E7283). An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. Cancer. 1995;76(10):1731-1736.

76 Shepherd NA, Scholefield JH, Love SB, et al. Prognostic factors in anal squamous carcinoma. A multivariate analysis of clinical, pathological and flow cytometric parameters in 235 cases. Histopathology. 1990;16(6):545-555.

94 Nguyen BT, Joon DL, Khoo V, et al. Assessing the impact of FDG-PET in the management of anal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2008;87(3):376-382.

95 Iagaru A, Kundu R, Jadvar H, et al. Evaluation by 18F-FDG-PET of patients with anal squamous cell carcinoma. Hell J Nucl Med. 2009;12(1):26-29.

96 Trautmann TG, Zuger JH. Positron emission tomography for pretreatment staging and posttreatment evaluation in cancer of the anal canal. Mol Imaging Biol. 2005;7(4):309-313.

97 Cotter SE, Grigsby PW, Siegel BA, et al. FDG-PET/CT in the evaluation of anal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(3):720-725.

98 Winton E, Heriot AG, Ng M, et al. The impact of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography on the staging, management and outcome of anal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(5):693-700.

99 Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, et al. Tumor response and survival predicted by post-therapy FDG-PET/CT in anal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(1):180-186.

102 Martenson JAJr, Gunderson LL. External radiation therapy without chemotherapy in the management of anal cancer. Cancer. 1993;71(5):1736-1740.

104 UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party. Epidermoid anal cancer. Results from the UKCCCR randomised trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, and mitomycin. UK Co-ordinating Committee on Cancer Research. Lancet. 1996;348(9034):1049-1054.

105 Bosset JF, Pavy JJ, Roelofsen F, et al. Combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy for anal cancer. EORTC Radiotherapy and Gastrointestinal Cooperative Groups. Lancet. 1997;349(9046):205-206.

106 Nigro ND, Seydel HG, Considine B, et al. Combined preoperative radiation and chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Cancer. 1983;51(10):1826-1829.

107 Flam M, John M, Pajak TF, et al. Role of mitomycin in combination with fluorouracil and radiotherapy, and of salvage chemoradiation in the definitive nonsurgical treatment of epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Results of a phase III randomized intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(9):2527-2539.

114 Flam M, John M, Pajak TF. Radiation (RT) and 5-fluorouracil (5FU) vs. radiation, 5FU, and mitomycin-C (MMC) in the treatment of anal carcinoma. Results of a phase III randomized RTOG/ECOG intergroup trial (abstract). Prog Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1995;14:191.

116 Gerard JP, Ayzac L, Hun D, et al. Treatment of anal canal carcinoma with high dose radiation therapy and concomitant fluorouracil-cisplatinum. Long-term results in 95 patients. Radiother Oncol. 1998;46(3):249-256.

117 Hung A, Crane C, Delclos M, et al. Cisplatin-based combined modality therapy for anal carcinoma. A wider therapeutic index. Cancer. 2003;97(5):1195-1202.

118 Doci R, Zucali R, Bombelli L, et al. Combined chemoradiation therapy for anal cancer. A report of 56 cases. Ann Surg. 1992;215(2):150-156.

119 Martenson JA, Lipsitz SR, Wagner HJr, et al. Initial results of a phase II trial of high dose radiation therapy, 5-fluorouracil, and cisplatin for patients with anal cancer (E4292). An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35(4):745-749.

120 Peiffert D, Giovannini M, Ducreux M, et al. High-dose radiation therapy and neoadjuvant plus concomitant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin in patients with locally advanced squamous-cell anal canal cancer. Final results of a phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(3):397-404.

121 Meropol NJ, Niedzwiecki D, Shank B, et al. Induction therapy for poor-prognosis anal canal carcinoma. A phase II study of the cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 9281). J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3229-3234.

122 Ajani JA, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, et al. Fluorouracil, mitomycin, and radiotherapy vs fluorouracil, cisplatin, and radiotherapy for carcinoma of the anal canal. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(16):1914-1921.

125 Allal AS, Mermillod B, Roth AD, et al. The impact of treatment factors on local control in T2-T3 anal carcinomas treated by radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Cancer. 1997;79(12):2329-2335.

126 Ajani JA, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, et al. US intergroup anal carcinoma trial. Tumor diameter predicts for colostomy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(7):1116-1121.

128 Das P, Bhatia S, Eng C, et al. Predictors and patterns of recurrence after definitive chemoradiation for anal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68(3):794-800.

129 Myerson RJ, Garofalo MC, El Naqa I, et al. Elective clinical target volumes for conformal therapy in anorectal cancer. A radiation therapy oncology group consensus panel contouring atlas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(3):824-830.

130 Menkarios C, Azria D, Laliberte B, et al. Optimal organ-sparing intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) regimen for the treatment of locally advanced anal canal carcinoma. A comparison of conventional and IMRT plans. Radiat Oncol. 2007;2:41.

131 Milano MT, Jani AB, Farrey KJ, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in the treatment of anal cancer: toxicity and clinical outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(2):354-361.

132 Salama JK, Mell LK, Schomas DA, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for anal canal cancer patients. A multicenter experience. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4581-4586.

133 Kachnic L, Winter KA, Myerson RJ, et al. RTOG 0529. A phase II evaluation of dose-painted IMRT in combination with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin-C for reduction of acute morbidity in carcinoma of the anal canal. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(3):S5.

135 Widder J, Kastenberger R, Fercher E, et al. Radiation dose associated with local control in advanced anal cancer. Retrospective analysis of 129 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2008;87(3):367-375.

136 Hatfield P, Cooper R, Sebag-Montefiore D. Involved-field, low-dose chemoradiotherapy for early-stage anal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70(2):419-424.

137 Hu K, Minsky BD, Cohen AM, et al. 30 Gy may be an adequate dose in patients with anal cancer treated with excisional biopsy followed by combined-modality therapy. J Surg Oncol. 1999;70(2):71-77.

140 Ben-Joseph E, Moughan J, Ajani JA, et al. The impact of overall treatment time on survival and local control in anal cancer patients. A pooled data analysis of RTOG trials 8704 and 9811. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(3):S26-S27.

141 Chapet O, Gerard JP, Riche B, et al. Prognostic value of tumor regression evaluated after first course of radiotherapy for anal canal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(5):1316-1324.

146 Oehler-Janne C, Huguet F, Provencher S, et al. HIV-specific differences in outcome of squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. A multicentric cohort study of HIV-positive patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15):2550-2557.

147 Fraunholz I, Weiss C, Eberlein K, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C for invasive anal carcinoma in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(5):1425-1432.

148 Abramowitz L, Mathieu N, Roudot-Thoraval F, et al. Epidermoid anal cancer prognosis comparison among HIV+ and HIV− patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(4):414-421.

149 Myerson RJ, Outlaw ED, Chang A, et al. Radiotherapy for epidermoid carcinoma of the anus. Thirty years’ experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(2):428-435.

150 Seo Y, Kinsella MT, Reynolds HL, et al. Outcomes of chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C for anal cancer in immunocompetent versus immunodeficient patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(1):143-149.

151 Wexler A, Berson AM, Goldstone SE, et al. Invasive anal squamous-cell carcinoma in the HIV-positive patient. Outcome in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):73-81.

152 Hogg ME, Popowich DA, Wang EC, et al. HIV and anal cancer outcomes. A single institution’s experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(5):891-897.

1 Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277-300.

2 McConnell EM. Squamous carcinoma of the anus—a review of 96 cases. Br J Surg. 1970;57(2):89-92.

3 Stearns MWJr, Urmacher C, Sternberg SS, et al. Cancer of the anal canal. Curr Probl Cancer. 1980;4(12):1-44.

4 Sischy B, Doggett RL, Krall JM, et al. Definitive irradiation and chemotherapy for radiosensitization in management of anal carcinoma. Interim report on Radiation Therapy Oncology Group study no. 8314. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(11):850-856.

5 Goldman S, Glimelius B, Nilsson B, et al. Incidence of anal epidermoid carcinoma in Sweden 1970-1984. Acta Chir Scand. 1989;155(3):191-197.

6 Melbye M, Rabkin C, Frisch M, et al. Changing patterns of anal cancer incidence in the United States, 1940-1989. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139(8):772-780.

7 Myerson RJ, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on carcinoma of the anus. Cancer. 1997;80(4):805-815.

8 Frisch M, Melbye M, Moller H. Trends in incidence of anal cancer in Denmark. Br Med J. 1993;306(6875):419-422.

9 Peters RK, Mack TM. Patterns of anal carcinoma by gender and marital status in Los Angeles County. Br J Cancer. 1983;48(5):629-636.

10 Biggar RJ, Burnett W, Mikl J, et al. Cancer among New York men at risk of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Int J Cancer. 1989;43(6):979-985.

11 Austin DF. Etiological clues from descriptive epidemiology. Squamous carcinoma of the rectum or anus. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1982;62:89-90.

12 Daling JR, Weiss NS, Klopfenstein LL, et al. Correlates of homosexual behavior and the incidence of anal cancer. JAMA. 1982;247(14):1988-1990.

13 Levi F, La Vecchia C, Randimbison L, et al. Patterns of large bowel cancer by subsite, age, sex and marital status. Tumori. 1991;77(3):246-251.

14 Beahrs OH, Wilson SM. Carcinoma of the anus. Ann Surg. 1976;184(4):422-428.

15 Frisch M, Smith E, Grulich A, et al. Cancer in a population-based cohort of men and women in registered homosexual partnerships. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(11):966-972.

16 Melbye M, Cote TR, Kessler L, et al. High incidence of anal cancer among AIDS patients. The AIDS/Cancer Working Group. Lancet. 1994;343(8898):636-639.

17 Frisch M, Olsen JH, Melbye M. Malignancies that occur before and after anal cancer. Clues to their etiology. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(1):12-19.

18 Ogunbiyi OA, Scholefield JH, Rogers K, et al. C-myc oncogene expression in anal squamous neoplasia. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46(1):23-27.

19 Escot C, Theillet C, Lidereau R, et al. Genetic alteration of the c-myc protooncogene (MYC) in human primary breast carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(13):4834-4838.

20 Melbye M, Sprogel P. Aetiological parallel between anal cancer and cervical cancer. Lancet. 1991;338(8768):657-659.

21 Cabrera A, Tsukada Y, Pickren JW, et al. Development of lower genital carcinomas in patients with anal carcinoma. A more than casual relationship. Cancer. 1966;19(4):470-480.

22 Holmes F, Borek D, Owen-Kummer M, et al. Anal cancer in women. Gastroenterology. 1988;95(1):107-111.

23 Wexner SD, Milsom JW, Dailey TH. The demographics of anal cancers are changing. Identification of a high-risk population. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30(12):942-946.

24 Daling JR, Weiss NS, Hislop TG, et al. Sexual practices, sexually transmitted diseases, and the incidence of anal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(16):973-977.

25 Zaki SR, Judd R, Coffield LM, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and anal carcinoma. Retrospective analysis by in situ hybridization and the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Pathol. 1992;140(6):1345-1355.

26 Holly EA, Whittemore AS, Aston DA, et al. Anal cancer incidence: genital warts, anal fissure or fistula, hemorrhoids, and smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(22):1726-1731.

27 Friis S, Kjaer SK, Frisch M, et al. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, anogenital cancer, and other cancer types in women after hospitalization for condylomata acuminata. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(4):743-748.

28 Heino P, Goldman S, Lagerstedt U, et al. Molecular and serological studies of human papillomavirus among patients with anal epidermoid carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1993;53(3):377-381.