CHAPTER 2 Local anaesthetic toxidromes and complications

Local complications

Local complications are usually a result of the injection technique. Immediate complications include pain, bruising, haematoma formation, local skin reactions (dermatitis) and nerve injury. Delayed complications include infection, complicated haematomas and neurapraxias.

Systemic complications

Systemic complications include hypersensitivity reactions, anaphylaxis and toxicity of the local anaesthetic agent.

Allergic reactions, in all forms, are idiosyncratic and can occur at any dose. They are more common with the ester local anaesthetics, but can occur with any medication. Allergic reactions can be in response to the local anaesthetic agent or to the preservative agent (e.g. methyl hydroxybenzoate). Anaphylactic reactions should be treated with intramuscular adrenaline (epinephrine) (0.5 mg in the anterolateral thigh for adults), intravenous fluids, intravenous steroids (e.g. hydrocortisone 4 mg/kg) and possibly intravenous antihistamines (e.g. promethazine 0.5 mg/kg). Resuscitation equipment should always be available in an environment where local or regional anaesthesia is practised.

Methaemoglobinaemia may be caused by any local anaesthetic agent, but prilocaine is the most common culprit, especially in children. Methaemoglobinaemia can produce clinically significant hypoxaemia and can interfere with pulse oximetry, producing an exaggeratedly low saturation figure (around 85%). Treatment is with intravenous methylene blue 1 mg/kg.

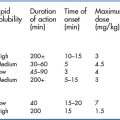

Systemic adverse effects usually occur when blood concentrations of local anaesthetic increase to toxic levels. These effects are most often encountered after inadvertent intravenous injection, systemic release of local anaesthetic after intravenous regional anaesthesia, or administration of an excessive dose of a local anaesthetic or topical agent (especially on broken skin or mucous membranes). Patients in the ED are particularly at risk since the trauma patient may get local anaesthetic for the placement of an intercostal drain, for the central venous catheter, for wound repair, topical anaesthesia of the upper airway, an intrapleural block and so on.

Patients with decreased pseudocholinesterase activity are more susceptible to toxicity from ester anaesthetics and patients who are taking medications that inhibit the cytochrome P450 system (e.g. propofol, amiodarone, ciprofloxacin, macrolides, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, cimetidine, imidazole antifungals, antiepileptic medications, benzodiazepines, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, statins, immunosuppressants, and antiviral agents) are more susceptible to toxicity from amide anaesthetics.

The systemic toxicity of local anaesthetic agents affects the central nervous system (CNS) and the cardiovascular system. CNS lidocaine toxicity is biphasic and as the serum levels of lidocaine increases, the effects on the CNS become more severe. The first phase of side effects occurs as a result of CNS excitation and can include irritability and seizures. The second phase causes CNS depression. The seizures stop (and not because the patient is getting better) and coma and respiratory depression or arrest may develop. This biphasic effect occurs because local anaesthetics first block inhibitory CNS pathways (resulting in stimulation) and then eventually block both inhibitory and excitatory pathways (resulting in overall CNS inhibition).

Resuscitation of these patients should follow a standard Advanced Life Support algorithm (the ABCD approach) with an emphasis on avoiding hypoxia, hypercapnia and acidaemia as this increases the toxicity of local anaesthetics. Seizures should be managed with intravenous benzodiazepines (e.g. lorazepam or diazepam). Significant persistent neurological abnormalities have not been documented following seizures induced by local anaesthetic toxicity.

Many of the adverse effects affecting the cardiovascular system that occur with the administration of local anaesthetics may be as a result of the addition of adrenaline rather than direct effects of the anaesthetic itself (such as tachycardia and hypertension). However, high blood levels of local anaesthetics directly reduce cardiac contractility and cause vasodilatation, which can result in hypotension. Atrioventricular blocks, bradycardia, and ventricular arrhythmias can occur; but these are more common in patients with underlying conduction abnormalities. The management of hypotension should be symptomatic with intravenous fluids (e.g. warm Ringer’s lactate or Balsol) and vasopressors used as needed (ephedrine for transient hypotension and adrenaline for sustained hypotension). Hypertension should be treated with intravenous benzodiazepines, and not any other medications. Ventricular tachycardia should be treated with amiodarone. Most other arrhythmias require only symptomatic treatment.

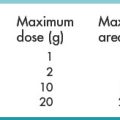

Cardiac arrest following local anaesthetic toxicity that is refractive to conventional resuscitation techniques may respond to treatment with a lipid emulsion – there are case reports of success with this protocol: a 1.5 mL/kg bolus of a 20% solution over 1 minute, followed by an infusion at a rate of 0.25 mL/kg/min. The bolus may be repeated twice every 3 to 5 minutes or until the return of spontaneous circulation. The infusion should be continued until haemodynamic stability is achieved and the rate increased to 0.5 mL/kg/min if the blood pressure drops. A total dose of 8 mL/kg should not be exceeded. If lipid emulsion is not available, an induction dose of propofol (which is buffered in a 13% lipid emulsion) followed by an infusion may be considered instead.