CHAPTER 11 Procedural sedation and analgesia

Introduction

Pain is one of the most common reasons for patients to present to the ED and it is a reasonable expectation that their pain will be swiftly and skilfully managed. Similarly, patients in the ED often require diagnostic or therapeutic procedures that may cause apprehension or pain, or both. Patient dissatisfaction often relates to poor management of pain and anxiety or an inappropriate approach to the management of procedures. Emergency physicians are well qualified to administer procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) while simultaneously monitoring the respiratory and cardiovascular status of both critically ill or injured patients and those with less dramatic but nonetheless painful conditions. Adequate analgesia and sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions should be the standard of care in the ED.

The provision of safe and effective sedation and analgesia (for procedures or otherwise) is an important part of Emergency Medicine practice. The failure to adequately treat a patient’s pain can have negative consequences, potentially affecting later psychological and physiologic responses and behaviours, especially in children. Appropriately treating pain and anxiety decreases patient suffering, facilitates medical interventions, increases patient/family satisfaction, improves patient care, and may improve patient outcome.

Providing effective and safe PSA in the ED is dependent on a number of factors:

There are many drugs and various non-pharmacologic modalities that can be used for PSA. The selection of a particular agent or modality is influenced by many factors, including patient characteristics (age, diagnosis, other illnesses, allergies) and the procedure to be performed (painful or painless, duration, depth of sedation required). Appropriate experience, staffing, equipment, monitoring and assessment are critical for safe and effective PSA.

Some of the myths that surround the use of analgesia in the ED negatively impact on the adequate and appropriate use of analgesic agents to treat pain and to be used as part of PSA. Some of these myths include:

What is PSA?

PSA involves the administration of sedative or dissociative agents with or without analgesic agents to induce a state that allows the patient to tolerate unpleasant or painful procedures. During the procedure, the patient maintains control of their airway and breathing because the protective airway and breathing reflexes are preserved. While PSA causes the patient to have a depressed level of consciousness, it allows them to maintain cardiorespiratory function.

Depth of sedation

Four levels of sedation have been defined by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA):

These somewhat arbitrary categories are part of a continuum through which the patient may drift to a lighter or deeper sedative state. Individuals may also vary in their responses to the initial dose of a specific sedative with a resulting lighter or deeper sedation than intended. Physicians administering PSA should be proficient in the skills needed to rescue a patient at a level greater than the desired level of sedation. If moderate sedation is desired, the practitioner should be able to provide the skills needed to perform deep sedation. If deep sedation is required, the practitioner should be competent in the airway management and cardiovascular support involved in providing general anaesthesia.

Dissociative sedation, as produced by ketamine, is another form of sedation where a trance-like state is induced which provides analgesia and amnesia whilst leaving protective airway reflexes and cardiovascular stability unaffected. It cannot be categorised into any of the above levels of sedation.

How to perform PSA

The main aims for this chapter on PSA are to provide, or revise, some basic principles that can be used to improve patient care using an evidence-based approach. The physician should be able to ensure:

In order to perform PSA safely in the ED according to evidence-based recommendations, there are seven key questions which need to be considered:

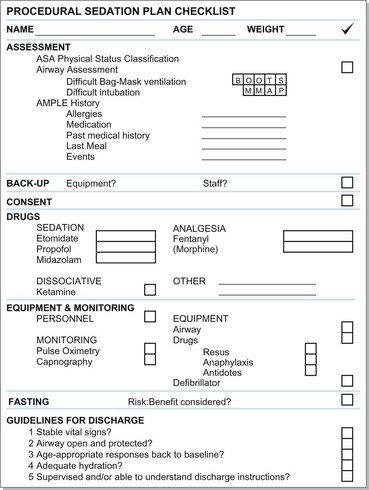

So where do we start and how do we apply this in creating a plan for PSA? It’s as easy as ABC (Fig. 11.1):

Assessment

The assessment of the patient pre-PSA requires some additional information over and above the basic history and examination that has probably already been performed. Focus on the following:

Children under the age of 2 years should generally receive PSA from a specialist with expertise in the management of infants.

ASA physical status classification

The ASA stratifies patients who will be undergoing anaesthesia according to a physical status classification (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1 ASA physical status classification

| Class 1 | Normally healthy patient |

| Class 2 | Mild systemic disease |

| Class 3 | Severe systemic disease, but not incapacitating |

| Class 4 | Severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life |

| Class 5 | Moribund, not expected to survive without the procedure |

The limitation of this classification is that it was developed using general anaesthesia guidelines. Its utility in the emergent PSA application has not yet been formally established. Patients who fall into ASA class 3 or above have been shown to have a greater risk of sedation-related adverse events. It is generally accepted that patients in ASA classes 1 and 2 can safely undergo procedural sedation in the ED. ASA class 3 patients can be considered for ED procedural sedation – the potential risks and benefits should be taken into account, e.g. an awake patient with a supraventricular tachycardia requiring sedation for electrical cardioversion.

Airway assessment

In many ED scenarios the urgency of airway management does not always allow for the evaluation of a patient’s airway in advance. This sometimes leads to the uncomfortable finding of an unanticipated difficult airway for which you are not prepared (unless you consider that every airway is going to be difficult!).

PSA can be considered to be semi-elective. It is therefore essential to assess your patient’s airway prior to the performance of the procedure in order to have the relevant back-up equipment/medical staff available should the patient require airway and ventilatory management. This assessment should include predicting difficult bag–mask ventilation and intubation. Awareness of abnormal airway anatomy (e.g. micrognathia or macroglossia), the presence of dental appliances or false teeth, a full beard, facial piercings, limited neck mobility, a short neck or history of stridor may all predict a difficult airway. The procedure should then be deferred to the operating theatre. The Mallampati score given for the view on mouth opening can also be added to the assessment process.

A useful aide-mémoire to recall the potential causes of difficult bag–mask ventilation is BOOTS.

The mnemonic MMAP can be used to assess the patient’s anatomy for possible difficult laryngoscopy.

AMPLE history

The AMPLE mnemonic is useful in your initial patient assessment.

Back-up/background

PSA should not be taken lightly. As with all patient interventions, there are benefits as well as potential adverse events of which the physician should be aware. The safety and efficacy of PSA is unequivocal as long as safe practice guidelines are followed. Background knowledge of PSA is fundamental to its sound performance.

Although the goal of procedural sedation is to induce mild to moderate or dissociative sedation, the patient’s level of sedation may fluctuate due to individual variations in their response to the medication, so the physician must be competent in the skills required to rescue a patient whose level of sedation becomes deeper than that desired. The physician should also be well versed in the different drug options, their indications and contraindications, and be able to make an appropriate choice for the selected procedure.

Should there be any doubt in the practitioner’s mind as to the patient’s safety prior to or while performing PSA, its practice should be deferred and an alternative means sought (e.g. procedure performed in the operating theatre).

Back-up equipment, resuscitation equipment and drugs, as well as trained staff should always be at hand in case of an adverse event.

Consent

Informed consent should be obtained from the patient, parent or legal guardian. Ideally, this should be written consent but will depend on the policy of the hospital or department in which you are working.

The patient/parent should be told about the proposed order of events (including the need for post-procedural monitoring prior to discharge), potential complications, and alternative options available to them. Parents must specifically be warned about the changes they may see in their child during the procedural sedation. This is especially true for the effects of dissociative agents such as ketamine, which can commonly cause nystagmus, excessive salivation, non-specific crying (on induction, intra-procedure and on arousal) and strange movements which may be disconcerting for the parents.

Drugs

Knowledge of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the drugs used is paramount to the success of the procedural sedation. There is a variety of drugs that can be used alone or in combination, administered via a range of different routes, in order to achieve the goal of safe and effective procedural sedation.

The ideal drug or drug combination should have a rapid onset of action, a short duration of action, be easily titrated to the desired effect, have a low adverse-effect profile, and be inexpensive. Although this has not been completely attainable to date, certain drugs/combinations have come close.

Children must always be weighed in order to accurately calculate dosages of drugs.

Routes of administration

The route chosen for drug administration will depend on drug availability, patient choice, paediatric considerations, physician choice and familiarity, duration of the procedure, and the volume of drug to be administered.

Drug availability

The ED where you work may not stock a drug that has the option of multiple different routes (e.g. ketamine), or may only have a drug which has to be given intravenously (e.g. propofol).

Patient choice

Children (and some adults) might not consent to the use of a needle for drug administration. The oral or nasal routes might then have to be considered.

Paediatric considerations

A once-off intramuscular injection may be preferred to the ‘torture’ which may be associated with obtaining intravenous access or the delay in waiting for topical anaesthesia to take effect at a prospective venous access site.

Physician choice and familiarity

This applies to the choice of drug as well as to the route of administration. Despite the security of being accustomed to a certain drug, the best and most appropriate drug for the procedure should be used. The physician practising PSA should become well acquainted at least with etomidate, fentanyl, ketamine, midazolam and propofol.

Duration of procedure

Intravenous administration generally has the quickest onset and duration of action amongst all the possible routes of administration. This is useful for quick procedures and can also be useful to titrate a drug if the procedure becomes prolonged. Intramuscular administration is not as easily titrated or predictable and has a longer duration of onset and time to recovery.

Sedative agents

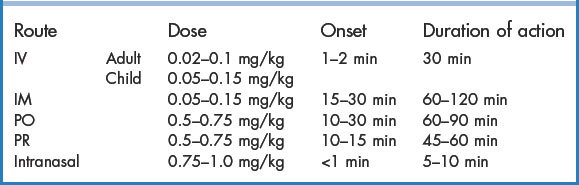

Midazolam

Midazolam is the benzodiazepine ‘work-horse’ of the ED. The beneficial effects of midazolam include good amnesia and anxiolysis, a relatively short onset of action, and multiple possible routes of administration. It also has anticonvulsant and muscle relaxant properties. The duration of action is approximately 30 minutes when given intravenously, which is much longer than the other sedative agents (Table 11.2). Midazolam has no analgesic properties, so should be administered with an opiate for painful procedures. This can prolong the predicted recovery time and increase the potential complications. It can cause respiratory depression but usually does not result in cardiovascular compromise in the comparatively low doses used for PSA. The dose should be halved in elderly patients. Owing to the different pharmacokinetics of midazolam in children, the recommended dose used is slightly higher, but paradoxical agitation is not uncommon.

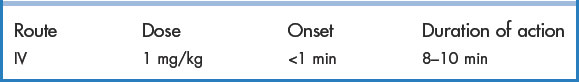

Propofol

Propofol is an ultra-rapid-acting sedative–hypnotic. It has a very rapid onset, with a duration of action usually less than 10 minutes (Table 11.3). Besides these obvious favourable benefits, propofol is also advantageous because of its antiemetic and anticonvulsant properties. Respiratory depression and apnoea may occur, but are of brief duration and easily remedied by oxygen administration or bag–mask ventilation if necessary. Hypotension is also a frequent occurrence and the drug should therefore be avoided in hypotensive patients. Propofol has no analgesic properties, so should typically be administered with a short-acting opioid. Pain on injection is improved by mixing the drug with a small amount (0.25 mg/kg) of intravenous lidocaine. Propofol is contraindicated in patients who are allergic to egg or soya. Repeated doses may be given at 5-minute intervals as required, at half the initial dose (i.e. 0.5 mg/kg).

Etomidate

Etomidate is a rapidly acting sedative commonly used for rapid sequence intubation in the haemodynamically unstable patient. It approaches the ideal procedural sedation agent because it has a rapid onset of action, short duration of action and a mild adverse effect profile (Table 11.4). It does not have any analgesic properties. Etomidate causes a transient reduction in cerebral blood flow, which is thought to be cerebrally protective. It also has relatively little effect on the cardiovascular system. These features make it a good choice for patients who may be haemodynamically compromised or have raised intracranial pressure. Myoclonus is a common side effect, which can sometimes be mistaken for a seizure. Vomiting and respiratory depression are not uncommon. Etomidate does cause adrenal suppression – controversy exists as to whether this is clinically relevant to the patient’s outcome.

Analgesic agents

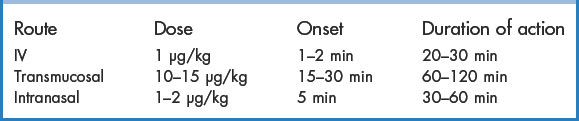

Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a rapidly acting, high-potency opioid with a short duration of action and favourable side-effect profile (Table 11.5). These features make it the opioid of choice for PSA. Its versatility is further enhanced by a choice of administration routes – intravenous, oral transmucosal and nasal. Adverse effects include respiratory depression, muscular and glottic rigidity, facial pruritus, nausea and vomiting. Rigidity can be overcome with naloxone or succinylcholine.

Dissociative agents

Ketamine

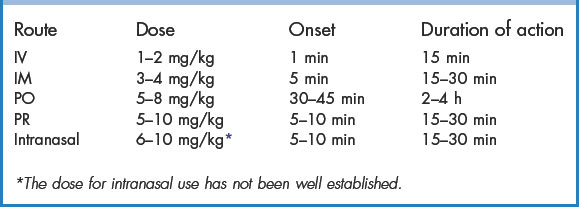

The trance-like state induced by ketamine, together with its powerful analgesic properties, make it a unique PSA drug. It has the additional benefits of not causing respiratory depression or muscle relaxation; therefore, patients can still maintain their protective airway reflexes. Although most commonly employed in paediatric procedural sedation, ketamine has been shown to be equally safe in adult patients. Ketamine also has the convenience of multi-route administration (Table 11.6). Ketamine may stimulate salivary and airway secretions (especially in children), but the use of atropine (0.01 mg/kg, minimum dose 0.1 mg, maximum dose 0.5 mg) is not routinely needed. Vomiting and emergence phenomena are common side effects. Aspiration following ketamine is extremely rare though. The agitation that occurs on emergence is generally mild and rarely requires treatment besides reassurance. It is so safe, that there are case reports of 10-fold and even 100-fold overdoses in children that have resulted in no major morbidities or mortalities. It should be used with caution in infants younger than 3 months, in patients with pulmonary infections and in patients with cardiovascular disease (angina, cardiac failure, uncontrolled hypertension).

Non-invasive methods

Nitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a colourless, sweet-smelling gas and the oldest known anaesthetic agent. It is more commonly used by dentists and as an adjunct in anaesthesia. Nitrous oxide produces sedation, anxiolysis and analgesia in as little as 1 to 2 minutes. Its duration of action is also short – usually 3 to 5 minutes (Table 11.7). The analgesic properties of nitrous oxide are not as potent as its ability to provide sedation and anxiolysis, so for more painful procedures, opioid or local anaesthesia should be administered concurrently. Nitrous oxide is usually administered in concentrations of 30% to 50% in the ED. Owing to changes in partial pressure of the gas, higher concentrations (65% to 70%) are required at high altitude. Hypoxia is avoided by ensuring a minimum of 30% oxygen and close monitoring of the patient’s respiratory status. Administering nitrous oxide with an appropriate pre-emptive psychological input has been known to enhance its action and make it more effective at lower doses – for example, if a patient expects to fall asleep whilst inhaling nitrous oxide, they most probably will. Nitrous oxide should be administered in a well-ventilated area, preferably with a scavenger system in place, in order to prevent inhalation by ED staff. It is a known teratogen, so care should be exercised around pregnant patients and staff members. The best way of using nitrous oxide is via a self-administered mask with a demand-valve. This means that the patient needs to hold the mask to their face and generate 3 to 5 cm H2O of negative pressure in order to allow gas to flow. If the patient becomes too sedated, they will not be able to generate the negative pressure, or the mask may fall away, which will stop the delivery of the gas. Unfortunately, this technique does not work well in paediatric patients or those who are not cooperative. Nausea and vomiting are common adverse effects.

Sucrose

Mary Poppins was right – a ‘spoonful of sugar’ does help the ‘medicine go down’. This is especially true in infants less than 6 months of age, where 2 mL of a 24% oral sucrose solution (1 teaspoon of sugar in 20 mL of water) reduces the signs of distress caused by minor painful procedures. The usefulness of sucrose diminishes in infants older than 6 months. The efficacy of sucrose is enhanced in combination with non-nutritive sucking such as sucking on a pacifier. The sucrose is most effective when given approximately 2 minutes before the invasive procedure is attempted.

Equipment and monitoring

Appropriately trained personnel, correct equipment and adequate monitoring are integral for the safe administration of PSA.

Appropriately trained personnel

The minimum required personnel to safely administer PSA are a doctor and a registered nurse. It is safe for the same doctor to perform the PSA and the procedure. Should the procedure to be performed be complex and require the doctor’s full attention throughout, a second doctor should be brought in to monitor the patient’s clinical status during the procedure. The nurse must remain monitoring the patient after the procedure until the patient is fully awake and ready for discharge.

The doctor performing the procedural sedation must be competent in the skills required to rescue a patient from a level of sedation deeper than the desired level.

Equipment

All equipment that may be required for the PSA process as well as all resuscitation equipment must be checked and available at the patient’s bedside should there be any sedation-related complications. This includes:

Oxygen

The routine use of supplemental oxygen in PSA is debatable. On the one hand it is thought that it might cause a delay in detecting hypoventilation, as the patient’s oxygen saturation is maintained longer by the supplemental oxygen administration. On the other hand, drug-induced apnoea in a well-oxygenated patient is less likely to be troublesome.

Monitoring

Constant clinical assessment and vital signs monitoring are core principles in procedural sedation. Vital signs should be monitored continually. Documentation of the patient’s level of consciousness, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation should be recorded pre-procedure and then every 5 minutes until the patient has recovered.

Pulse oximetry

Pulse oximetry is a valuable method of monitoring the patient continuously and non-invasively. It is reliable in detecting decreases in oxygen saturation as well as changes in the patient’s heart rate. The limitation of pulse oximetry is in detecting early decreases in ventilation. A patient may develop hypoventilation, but a drop in the oxygen saturation will lag behind the onset of hypercarbia and apnoea. The concomitant administration of oxygen is also thought to mask this hypoventilation by delaying the detection of decreased oxygen saturation. Therefore, continuous clinical monitoring must be used in conjunction with pulse oximetry.

Capnometry

Hypoventilation is a common side effect of both the sedative and analgesic drugs used in procedural sedation. This can be identified earlier by non-invasively monitoring the patient’s end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) level. An increase in ETCO2 will detect inadequate ventilation earlier than oxygen desaturation would. The normal range for ETCO2 is between 40 and 48 mmHg.

Fasting

Conventional pre-operative guidelines promulgated by the ASA for patients undergoing general anaesthesia recommend a minimum nulla per os (NPO) period of 6 hours for solids, 4 hours for breast milk, and 2 hours for clear liquids. The idea behind this thinking is to prevent aspiration of gastric contents into the lungs, even though there is insufficient data to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between NPO times and adverse outcome prevention. These fasting guidelines have unfortunately been extrapolated to the ED for PSA, despite the very different environment and procedure to be performed. Whereas general anaesthesia routinely involves airway manipulation, which is known to increase the aspiration risk, PSA aims to have the patient maintain their own airway reflexes with no manipulation thereof. Studies have shown that aspiration is not linked to NPO times, so, whereas it is mandatory in general anaesthesia, fasting is a consideration but not a necessity for ED PSA.

The timing of the patient’s last meal should be documented. The risks of the sedation and remote possibility of aspiration must be balanced against the benefits of performing the procedure promptly and individualised to the patient and the situation.

Guidelines for discharge

The determination of discharge readiness should be individualised for each patient in order to ensure that the patient will not experience any serious or life-threatening adverse event at home.

The decision-making process should include the following criteria:

The clinician must also take into account the sedative and/or analgesic agent used, the route of administration and the duration of action, as well as whether any adverse events were experienced during the procedure.

The aim is to ensure early safe discharge from the ED; however, if any doubt exists as to the condition of the patient, it is better to err on the side of prolonged observation than premature discharge.

Summary

PSA has been devised based on demand and need. Pressure on theatre lists and the risks of general anaesthesia have created a niche for the practice of safe and effective PSA in the ED. A structured approach, adequate training and meticulous pre-procedural preparation will ensure the safety and satisfaction of both patient and doctor alike.

In summary, these elements are applied to the provision of PSA by means of a plan which consists of the following sequential steps:

Case studies

The ABCDEFG methodology applies to all patients who are to undergo PSA. Each case needs to be considered individually as to whether sedation, analgesia, regional anaesthesia or a combination thereof needs to be employed in order to facilitate the performance of a potentially unpleasant procedure. There will be variability amongst different healthcare practitioners as to their approach used for different procedures. No one option is necessarily better than another, as long as patient safety and comfort is the ultimate aim. The examples below are potential approaches which may be used for these typical scenarios.

Case 1

A 36-year-old, 75 kg male has been stabbed in his right chest. He is taken through to the ED. In the resuscitation room, the patient is attached to monitoring equipment, has oxygen administered and peripheral intravenous cannulation performed. The patient is diagnosed with a right-sided haemopneumothorax on x-ray. The consultant Emergency Physician tells the medical officer managing the case that the patient will require an intercostal drain (ICD) to be inserted.

The nurse reports that his vital signs are as follows:

| Blood pressure | 121/68 mmHg |

| Pulse | 82 beats per minute |

| Respiratory rate | 22 breaths per minute |

| Pulse oximetry | 99% on a partial rebreather mask at 15 L/min |

The patient is assessed by the medical officer to be ASA class 2 with a Mallampati class I airway and no signs of being potentially difficult to bag–mask ventilate or intubate. He has no allergies or previous medical or surgical history. His last meal was 4 hours ago. Verbal consent is obtained for PSA as well as for the insertion of the ICD.

The patient is given 75 µg of fentanyl intravenously and a 500 mL fluid bolus. The medical officer performs an intercostal block with 1% lidocaine. Three minutes later, 75 mg of propofol is slowly titrated intravenously over 1 minute. The intercostal drain is inserted uneventfully and 400 mL of blood drains into the bottle. The patient is monitored for 30 minutes post-procedure. He required a further 500 mL crystalloid fluid bolus but remained haemodynamically stable. He was awake and oriented, and given an intrapleural block with 0.5% bupivacaine before being transferred to the ward.

Case 2

A 6-year-old, 20 kg girl falls off the jungle-gym whilst playing at school. She comes into the ED crying, complaining of pain in her left wrist. An x-ray reveals a markedly angulated greenstick fracture of her left distal radius and ulna. The registrar on duty elects to use PSA in order to facilitate manipulation and splinting of the fracture. The patient is known to be a well-controlled asthmatic and is currently in good health. She last ate a meal 3 hours ago. Evaluation of her airway yields no disconcerting features. The patient is categorised as ASA class 2. The procedure is explained to the parents and written consent is obtained. EMLA cream had already been applied to the right antecubital fossa 1 hour previously, when the patient was initially triaged. An intravenous cannula is painlessly inserted and the young girl is taken through to the procedure room and attached to monitoring equipment. The registrar had checked the presence of resuscitation equipment and drug availability when she came on duty that morning. The child is given 20 mg of ketamine slowly intravenously. After 1 minute, she has nystagmus and is breathing spontaneously with adequate vital signs. The fracture is manipulated and a splint applied. The child cries briefly during the manipulation only. After 45 minutes, the patient is sleepy but arousable enough to be sent for a control x-ray accompanied by her parents. On her return, she is awake and communicative. The parents are given a copy of the discharge instructions and told to return should there be any concerns. Four weeks later, the child returns for a check-up. She runs towards the doctor and hugs her – thanking her for fixing her arm.

Case 3

A 62-year-old, 50 kg female slips on wet tiles at the supermarket and presents to the ED with an isolated anterior dislocation of her left shoulder. The patient is on various medications for her rheumatoid arthritis and hypertension. She is allergic to soya. The patient is assessed to be ASA class 3. She is a Mallampati class II but has severe limitation of movement of her atlanto-occipital joint due to the rheumatoid arthritis. In view of the patient’s chronic illness and frailty, the doctor opts to reduce the shoulder with a short-acting opioid and local anaesthesia.

He injects 20 mL of 0.5% lidocaine into the subacromial space under sterile conditions. After 20 minutes, he gives 25 µg of fentanyl. After waiting a further 2 minutes, he attempts to reduce the shoulder by scapular manipulation. He succeeds after the second attempt. The patient is monitored until fully conscious and discharged back to the retirement village in the care of her daughter.

Case 4

A 45-year-old, 80 kg male patient requires a computed tomography (CT) scan of his brain because of a seizure following a head injury. He is claustrophobic and terrified of entering the CT scanner. He has no alarming features on the focused assessment.

The Emergency Physician administers a small dose (2 mg) of lorazepam intravenously to induce minimal sedation (anxiolysis), after which the patient calmly submits to the CT examination. He requires no supplemental oxygen and the saturations remain above 95%. One hour after the CT scan, he can safely be discharged home in the company of his wife as he is fully awake and alert with an intact airway.