CHAPTER 1 Local anaesthesia

The administration of local anaesthetics is indicated whenever their use will ease pain from trauma, or decrease the discomfort of a painful procedure. Local anaesthesia is thus useful in many clinical situations to increase patient comfort and facilitate cooperation during painful procedures. The successful use of local anaesthesia can be maximised by an understanding of the pharmacokinetics of local anaesthetic agents, the indications for their use, appropriate methods of administration and techniques to minimise the pain of administration.

Pharmacology

Local anaesthetics reversibly block nerve impulse conduction by blocking open, voltage-gated sodium channels (and possibly also interfering with calcium channels), thereby inhibiting the action potential; they have additional anti-inflammatory effects mediated through interaction with G-protein receptors.

The onset of action depends on the individual agent and the dose delivered to the nerve. The more lipid soluble (lipophilic/hydrophobic) an agent is, the greater its potency and duration of action. Similarly, the smaller the local anaesthetic molecule is, the faster its dissociation from the receptor and the shorter its duration of action. All local anaesthetics, with the single exception of cocaine, are vasodilators, which increases the clearance of the agent; the addition of adrenaline (epinephrine) in a ratio of 1:80 000 to 1:400 000 causes optimum vasoconstriction for bleeding control and prolongation of action. The addition of adrenaline to long-acting agents does less to prolong their action than in short-acting agents. The use of adrenaline is traditionally avoided in areas of limited vascular supply (fingers, toes, penis, nose and ears) although there is no evidence to prove that this is in fact harmful. If excessive vasoconstriction occurs, the pH of the interstitial fluid drops, which will result in a decreased activity of the local anaesthetic. It is important, therefore, not to use vasoconstrictors in excessive concentrations (1:80 000 or less is most appropriate).

Systemic absorption of the agent depends principally on the vascularity of the injection site. The rate of absorption and the risk of toxicity increase as shown below:

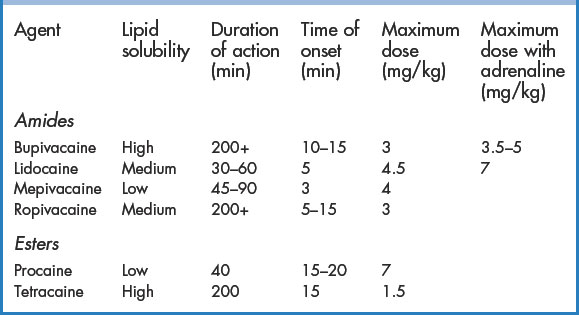

There are many local anaesthetics readily available in clinical practice (Table 1.1). The most widely used agents include lidocaine and bupivacaine. Local anaesthetics are most commonly used during wound repair and for minor procedures (drainage of abscesses etc.). Techniques for their administration in the ED include topical application, local infiltration, field block, and peripheral nerve block. Lidocaine, the most commonly used local anaesthetic, is inexpensive and is available in a variety of concentrations (1% and 2%) and volumes (20-mL vials, 5-mL ampoules, and 1.8-mL dental cartridges). Some formulations are appropriate for subcutaneous administration only. Only the IV preparation should be used for intravenous regional anaesthesia and haematoma blocks. The combination of 1% or 2% lidocaine with adrenaline in a ratio of 1:80 000 (found in dental cartridges or premixed vials) produces optimal skin vasoconstriction and adequate duration of effect for most procedures. If premixed solutions are not available, the addition of 0.1 mL of adrenaline 1:1000 to 10 mL of lidocaine will create a 1:100 000 solution. Bupivacaine has a much longer duration of action than lidocaine and therefore may be more appropriate for very complex wounds requiring long repair times or when prolonged post-procedure analgesia is required. In settings where wound care may be interrupted (in a busy ED), the use of bupivacaine may avoid the need for further administration of local anaesthesia to complete a wound repair. For these reasons, many ED physicians choose bupivacaine or ropivacaine over lidocaine. A mixture of the two agents is often used because of the rapid onset of lidocaine and the longer duration of bupivacaine and to increase the volume of injected agent for regional anaesthesia. Studies have suggested that bupivacaine is underused in the ED, mostly because it is unfamiliar or because doctors have misconceptions about its onset of action or safety. It is an excellent local anaesthetic for the ED!

Adverse events

Fortunately, true hypersensitivity reactions to local anaesthetics are rare and most commonly involve an ester agent (e.g. procaine, cocaine, tetracaine, benzocaine). Allergic reactions are very seldom caused by amide anaesthetic agents (e.g. lidocaine, bupivacaine, mepivacaine, ropivacaine). There is no cross-reactivity between the amide and ester agents whatsoever. An easy ‘rule of thumb’ method to distinguish between amide and ester agents is from the spelling convention of the generic name. Any local anaesthetic in which the letter ‘i’ appears in the prefix of the name is an amide agent (e.g. lidocaine). The ester agents do not contain an ‘i’ in the prefix (e.g. cocaine, benzocaine, procaine). If a patient is allergic to a particular agent from one class, an agent from the other class can safely be substituted.

Toxic adverse events are dose related; therefore, the maximum dose for any agent should not be exceeded (Table 1.1). Adverse reactions involve the central nervous system (CNS) and, to a lesser degree, the cardiovascular system (CVS).

Use smaller doses in debilitated patients, very young or very old patients, patients who are acutely ill, and those with cardiovascular disease or liver disease. Adrenaline, as an additive, should be avoided in hypertensive patients and those with cardiovascular or ischaemic heart disease.

Decreasing the pain of local anaesthesia

It is important, especially in children, to make the procedure of administering local anaesthesia as atraumatic (physically and psychologically) as possible. The pain of injecting the local anaesthetic is increased by the patient’s anxiety and apprehension and this needs to be addressed as carefully as the physical pain itself. The discomfort from the needlestick and from chemical irritation of the agent may be decreased somewhat by the following techniques:

Before injecting the local anaesthetic, make sure of the following:

For the safety of the healthcare provider, make sure of the following:

Basic infiltration techniques

Local anaesthesia may be obtained by injecting a local anaesthetic agent directly into the wound or by infiltrating as a field block. Intradermal injection has the advantages of a rapid onset of action after injection and an increased duration of anaesthesia compared with that of deeper anaesthetic placement. However, intradermal injection significantly distorts the tissues, and it is more painful than subcutaneous injection. For most purposes, local anaesthetic injected at the dermal–subcutaneous junction is ideal: the injection is not too painful and the anaesthetic results are excellent. As a rule, subcutaneous infiltration should not begin until it has been confirmed that the needle has not penetrated a vessel (pull back on the plunger of the syringe to ensure that blood is not aspirated). This technique is not reliable when a 30G needle is used (it is too small for blood to be aspirated).

Direct wound infiltration

Injection through the wound itself into the surrounding skin edges is less painful than injecting through the skin, especially if local anaesthetic is dripped into the wound beforehand, or if topical anaesthesia is used. Although this theoretically has the risk of transporting bacteria from the wound into the surrounding tissue, this has not been proven to result in a higher complication rate. It would seem appropriate, however, that this should not be performed on a heavily contaminated wound.

Parallel field block

This is more appropriate for complex wounds, contaminated wounds, wounds that require debridement or simple flaps. The needle is inserted at one end of the wound and advanced to the other end of the wound, parallel to it. After aspiration to ensure the needle has not penetrated a vessel, local anaesthetic is injected slowly as the needle is slowly withdrawn. Injection may be in the dermis (superficial anaesthesia, painful technique) or more commonly at the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue: this takes a bit longer to achieve anaesthesia (5 to 10 minutes), but is less painful. This procedure should be repeated until there are parallel tracks on both sides of the wound.

Circular field block

If the wound is irregular or complex, local anaesthetic can be infiltrated in a circular pattern at some distance from the wound edge, in the same method as described above. This technique is extremely useful for procedures on the ear. A circumference of subcutaneous local anaesthetic is infiltrated inferior, superior, anterior and posterior to the pinna, which results in complete anaesthesia of the ear.

Special local anaesthetic applications

Local anaesthesia for line placement

The placement of central venous catheters and arterial cannulas can be made less unpleasant with the correct use of local anaesthesia.

Central line technique

Local anaesthesia for intercostal drain insertion

In the ED, chest drain insertion may be emergent (pneumothorax, haemothorax) or semi-emergent (pleural effusion, empyema or spontaneous pneumothorax). While the type of procedural sedation used may vary, the administration of the local anaesthetic remains much the same.

Technique

Local anaesthesia for lumbar puncture

Lumbar punctures can be rendered virtually painless by the correct administration of local anaesthetic. The recurrent spinal nerves exit the neural foramina and travel posteriorly to supply sensation to the posterior spinal structures. These nerves can easily be blocked. Lumbar puncture should always be performed with local anaesthesia and with procedural sedation (light sedation) if required, especially in children.

Technique