8

Amenorrhoea

Introduction

Amenorrhoea may be defined as the failure of menstruation to occur at the expected time.

It may be considered in two categories:

1. Primary amenorrhoea, when menstruation has never occurred.

2. Secondary amenorrhoea, when established menstruation ceases for 6 months or more.

Primary amenorrhoea

Failure to menstruate by the age of 16 is referred to as ‘primary amenorrhoea’. The likely cause of primary amenorrhoea depends on whether secondary sexual characteristics are present or not. If secondary sexual characteristics are absent, then the cause is most likely delayed puberty (see p. 45). If pubertal development is normal, then an anatomical cause should be suspected. The main ‘anatomical’ causes are:

![]() congenital absence of the uterus; this is due to a failure of the Müllerian ducts to develop

congenital absence of the uterus; this is due to a failure of the Müllerian ducts to develop

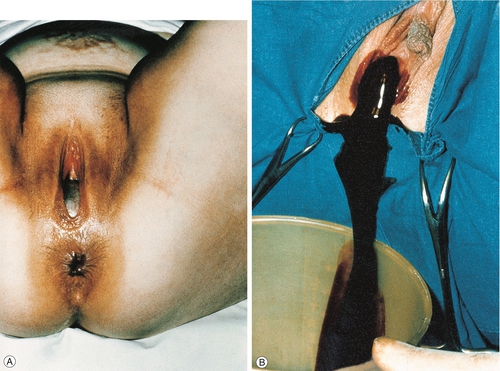

![]() imperforate hymen; the menstrual blood is retained within the vagina (a haematocolpos) causing cyclical lower abdominal pain each month at the time of menstruation (cryptomenorrhoea). Inspection of the vulva reveals a distended hymenal membrane through which dark blood may be seen and treatment by incision, usually under anaesthesia, is all that is required (Fig. 8.1).

imperforate hymen; the menstrual blood is retained within the vagina (a haematocolpos) causing cyclical lower abdominal pain each month at the time of menstruation (cryptomenorrhoea). Inspection of the vulva reveals a distended hymenal membrane through which dark blood may be seen and treatment by incision, usually under anaesthesia, is all that is required (Fig. 8.1).

Failure to menstruate may also be physiological delay, in other words, the development is normal but there is an inherent delay in the onset of menstruation. There is often a family history of the same delay in the mother. A progestogen challenge test is useful to identify constitutional menstrual delay. A progestogen (e.g. norethisterone) is given orally for 5 days, and withdrawal should lead to a vaginal bleed. If such a bleed occurs, it is reasonable to offer reassurance that spontaneous menstruation is likely to occur. An abdominal ultrasound may be reassuring to confirm that the uterus and ovaries are normal.

Low body weight and excessive exercise are also associated with primary amenorrhoea. The other causes listed in Table 8.1 are rare, although a few are outlined under the ‘secondary amenorrhoea’, discussion below (see also Chapters 5 and 6).

Table 8.1

Causes of primary amenorrhoea

| System | Problem | Incidence |

| Chromosomal | XO – Turner syndrome | Rare |

| 46,XY DSD | Rare | |

| Ovotesticular DSD | Rare | |

| Hypothalamic | Physiological delay | Common |

| Weight loss/anorexia/heavy exercise | Common | |

| Isolated GnRH deficiency | Rare | |

| Congenital CNS defects | Rare | |

| Intracranial tumours | Rare | |

| Pituitary | Partial/total hypopituitarism | Rare |

| Hyperprolactinaemia | Rare | |

| Pituitary adenoma | Rare | |

| Empty sella syndrome | Rare | |

| Trauma/surgery | Rare | |

| Ovarian | True agenesis | Rare |

| Premature ovarian failure | Rare | |

| Radiation/chemotherapy/autoimmune | Rare | |

| Polycystic ovaries | Common | |

| Virilizing ovarian tumours | Rare | |

| Other endocrine | Primary hypothyroidism | Rare |

| Adrenal hyperplasia | Rare | |

| Adrenal tumour | Rare | |

| Uterine/vaginal | Imperforate hymen | Not uncommon |

| Uterovaginal agenesis | Rare |

Secondary amenorrhoea

Secondary amenorrhoea means the cessation of established menstruation. It is defined as no menstruation for 6 months in the absence of pregnancy. A full list of causes is given in Table 8.2, but the commonest are weight loss, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and hyperprolactinaemia. The more common conditions are discussed below.

Table 8.2

Causes of secondary amenorrhoea

| System | Problem | Incidence |

| Physiological | Pregnancy | Common |

| Lactation | Common | |

| Menopause | Common | |

| Hypothalamic | Weight loss/anorexia | Common |

| Heavy exercise | Common | |

| Stress | Common | |

| Pituitary | Hyperprolactinaemia | Not uncommon |

| Partial/total hypopituitarism | Rare | |

| Trauma/surgery | Rare | |

| Ovarian | Polycystic ovary syndrome | Common |

| Premature ovarian failure | Uncommon | |

| Surgery/radiotherapy/chemotherapy | Uncommon | |

| Resistant ovary syndrome | Rare | |

| Virilizing ovarian tumours | Rare | |

| Other endocrine | Primary hypothyroidism | Rare |

| Adrenal hyperplasia | Rare | |

| Adrenal tumour | Rare | |

| Uterine/vaginal | Surgery – hysterectomy | Common |

| Endometrial ablation | Common | |

| Progestogen intrauterine device | Common | |

| Asherman syndrome | Rare |

Causes

Physiological

The commonest causes of amenorrhoea during the reproductive phase of life are physiological – pregnancy and lactation. Pregnancy should therefore be excluded in all sexually active women presenting with amenorrhoea.

The high postpartum level of prolactin associated with breastfeeding suppresses ovulation and gives rise to lactational amenorrhoea. The mechanism is probably related to reduced gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) production as a result of changes in the sensitivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis to oestrogen. Amenorrhoea usually persists throughout the time that the infant is fully breastfed, but with the introduction of supplementary feeding, and therefore reduction in the frequency of suckling, prolactin levels fall and ovarian activity is resumed. This hypo-oestrogenic state may lead to atrophic vaginitis, and occasionally to painful intercourse.

Hypothalamic

Hypothalamic amenorrhoea (‘hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism’) is frequently associated with stress, for example, leaving home for higher education, and in such cases, the condition usually resolves spontaneously. Physical stress in the form of athletic training can also result in suppression of the hypothalamo–pituitary–ovarian axis. There are low levels of pituitary gonadotrophins in association with low levels of prolactin and oestrogen.

If hypothalamic amenorrhoea is not related to low body weight (see below), treatment will depend on whether or not the woman wants to conceive. If pregnancy is not desired, oestrogen replacement therapy is advisable, and is conveniently provided in the form of the oral contraceptive pill. If the woman wishes to become pregnant, ovulation may be induced with pulsatile GnRH therapy or exogenous gonadotrophins (p. 75).

The hypothalamus is also sensitive to changes in body weight, and weight loss, even to only 10–15% below the ideal, may be associated with amenorrhoea. Anorexia nervosa should be considered. Restoration of the body weight results in the return of ovulatory function, although there may be a significant time interval between the attainment of the ideal body weight and the resumption of ovarian activity. Ovulation induction therapy is not recommended prior to the restoration of body weight, as pregnancy, if it occurs, carries the risk of growth restriction of the fetus and increased perinatal mortality.

Pituitary

Prolactin stimulates breast development and subsequent lactation. The secretion of prolactin, a polypeptide hormone produced by the lactotrophs of the anterior pituitary, is inhibited by dopamine from the hypothalamus. High levels of prolactin, which may be either physiological (during lactation) or pathological (see below), in turn suppress ovarian activity by interfering with the secretion of gonadotrophins.

Mildly elevated prolactin levels are common and can be due to stress (e.g. of venepuncture). Sustained higher levels can result in amenorrhoea and galactorrhoea unrelated to pregnancy. Galactorrhoea occurs in < 50% of those with hyperprolactinaemia, and < 50% of those with galactorrhoea have an elevated prolactin level. The causes of hyperprolactinaemia are given in Box 8.1.

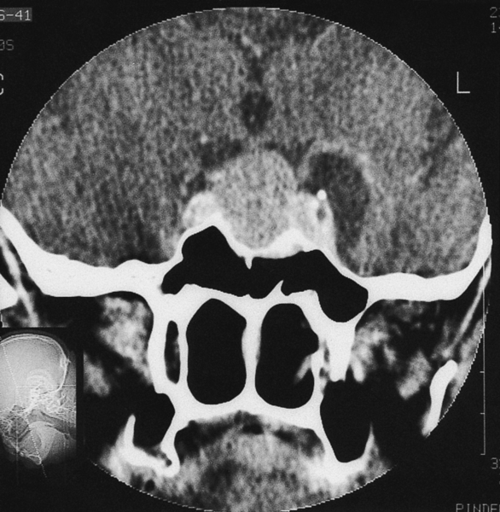

Adenomas occur in the lateral wings of the anterior pituitary and are usually soft and discrete with a pseudocapsule of compressed tissue (Fig. 8.2). If the prolactin is more than 1000 mU/L, then imaging with CT or (ideally) MRI should be carried out. A microadenoma is < 10 mm in diameter and a macroadenoma > 10 mm. Visual fields should be checked as optic chiasma compression may lead to bitemporal hemianopia. One-third of adenomas regress spontaneously and fewer than 5% of microadenomas become macroadenomas. Serum levels correlate well with tumour size, so that if the tumour is relatively large and the prolactin level only modestly elevated, then pituitary stalk compression from a non-secreting macroadenoma or other tumour is possible (e.g. a craniopharyngioma). It is possible that apparently idiopathic hyperprolactinaemia may be caused by microadenomas which are too small to be picked up by an MRI scan.

All patients should have pituitary imaging before treatment. This treatment is usually with a dopamine agonist, either bromocriptine or cabergoline, which suppresses the prolactin level and also induces regression of the prolactinoma. Transnasal transsphenoidal microsurgical excision of an adenoma is only rarely required.

Ovarian

Premature ovarian failure

The menopause (with cessation of ovarian function) normally occurs around the age of 50. The term ‘premature ovarian failure’ is usually used to describe cessation of ovarian function before the age of 40. As in the natural menopause, failure is usually due to depletion of primordial follicles in the ovaries.

Premature ovarian failure occurs in 1% of women and may be due to surgery, viral infections (e.g. mumps), cytotoxic drugs or radiotherapy. It may also be idiopathic and is occasionally associated with chromosomal abnormality (XO mosaics or XXX). A low oestrogen level, very high follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and the absence of any menstrual activity are poor prognostic signs for recovery. Pregnancy by in-vitro fertilization (IVF) with donor oocytes may be possible. There is an association with other autoimmune disorders. Hormone replacement therapy is required to relieve postmenopausal symptoms and minimize the risk of osteoporosis.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with menstrual disturbance, and is the most common form of anovulatory infertility. It is estimated to affect up to 20% of women in the UK. It is characterized by the presence of at least two out of the following three criteria:

![]() oligo- or amenorrhoea

oligo- or amenorrhoea

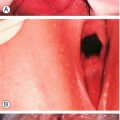

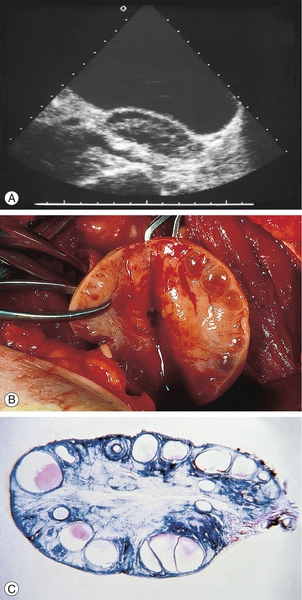

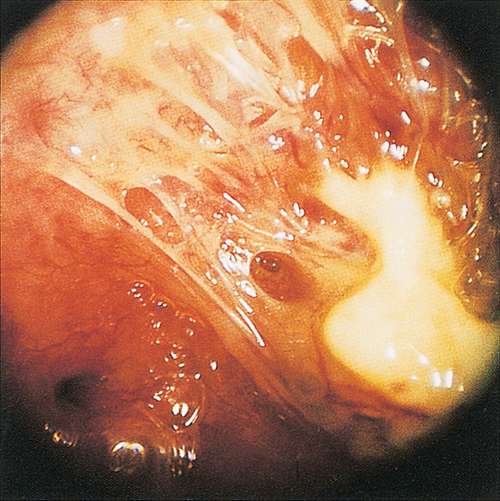

![]() ultrasound appearance of large-volume ovaries (> 10 cm3) and/or multiple small follicles (12 or more < 10 mm) (Fig. 8.3)

ultrasound appearance of large-volume ovaries (> 10 cm3) and/or multiple small follicles (12 or more < 10 mm) (Fig. 8.3)

These are classically bilaterally enlarged with multiple peripherally situated cysts ‘like a ring of pearls’ in a dense stroma: (A) ultrasound scan; (B) surgical dissection; (C) pathological preparation.

![]() clinical evidence of excess androgens (acne, hirsutism) or biochemical evidence (raised testosterone).

clinical evidence of excess androgens (acne, hirsutism) or biochemical evidence (raised testosterone).

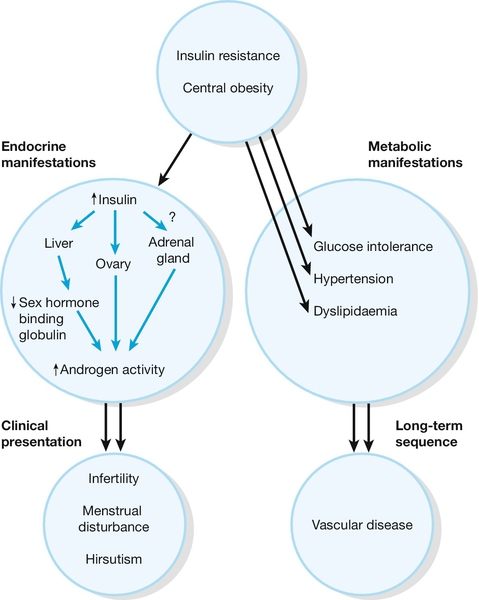

The aetiology of the condition is unknown, but recent evidence suggests that the principal underlying disorder is one of insulin resistance, with the resultant hyperinsulinaemia stimulating excess ovarian androgen production. Associated with the prevalent insulin resistance, there is a characteristic dyslipidaemia and a predisposition to non-insulin-dependent diabetes and cardiovascular disease in later life. PCOS may therefore be considered to be a systemic metabolic condition rather than one primarily of gynaecological origin (Fig. 8.4).

Fig. 8.4Pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome.

Polycystic ovary syndrome can be considered to be a disorder primarily of insulin resistance, with the resultant hyperinsulinaemia stimulating excess ovarian androgen production. There may also be dyslipidaemia and a predisposition to later non-insulin-dependent diabetes and cardiovascular disease.? = uncertain relationship between insulin and the adrenal gland.

Treatment depends on whether the presenting problem has been menstrual irregularity, hirsutism or infertility. The combined oral contraceptive pill has been used to regulate the menses. Hirsutism may be treated by cosmetic measures such as waxing or laser treatment. Hirsutism may also be treated with the combined oral contraceptive pill since it suppresses ovarian androgen production, or with the antiandrogen cyproterone acetate. Women taking an antiandrogen should use effective contraception during and for at least 3 months after treatment, due to the potential risk of teratogenicity (feminization of a male fetus) with antiandrogen therapy. Clomifene is used to induce ovulation in women with anovulatory infertility (p. 74). If clomifene does not work, ovulation may be induced by injections of gonadotrophins, or by laparoscopic laser or diathermy to the ovary.

The cornerstone to management, however, is weight reduction, which reduces insulin resistance, corrects the hormone imbalance and promotes ovulation. Although initial small studies of insulin-sensitizing agents (e.g. metformin) as a therapeutic option in the management of anovulation and other symptoms of PCOS were promising, recent larger trials have failed to demonstrate benefit.

Long term, there is an increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma as a consequence of the effects of anovulation with unopposed oestrogen stimulation of the endometrium. There is also an increased risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Individuals may gain benefit from early screening for cardiovascular risk factors, particularly hypertension and glucose intolerance.

Other endocrine causes

These are rare. Women with thyrotoxicosis may have amenorrhoea. Primary hypothyroidism is also associated with amenorrhoea, as thyrotrophin-releasing hormone stimulates prolactin secretion. The most common of the rare adrenal problems is late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia. This is usually due to a deficiency of the enzyme 21-hydroxylase (Fig. 6.4), and treatment with a low dose of corticosteroids is usually sufficient to re-establish ovulatory function by suppressing adrenal function. Androgen-secreting adrenal tumours can also occur.

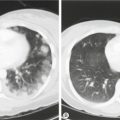

Uterine

Excessive uterine curettage – usually at the time of miscarriage, termination of pregnancy or secondary postpartum haemorrhage – may remove the basal layer of the endometrium and result in the formation of uterine adhesions (synechiae), a condition known as Asherman syndrome (Fig. 8.5) (see History box). It may rarely also result from severe postpartum infection. Treatment involves breaking down the adhesions through a hysteroscope with or without inserting an IUD to deter reformation.

Fig. 8.5Rarely, adhesions can form within the uterine cavity.

If so severe that they obstruct the menstrual flow, the condition is referred to as Asherman syndrome.

Summary of clinical management

Initial management:

![]() exclude pregnancy

exclude pregnancy

![]() ask about perimenopausal symptoms (e.g. flushings, vaginal dryness)

ask about perimenopausal symptoms (e.g. flushings, vaginal dryness)

![]() take a history, including weight changes, drugs, medical disorders and thyroid symptoms

take a history, including weight changes, drugs, medical disorders and thyroid symptoms

![]() carry out an examination, looking particularly at height, weight, visual fields and the presence of hirsutism or virilization; also carry out a pelvic examination, unless this is contraindicated

carry out an examination, looking particularly at height, weight, visual fields and the presence of hirsutism or virilization; also carry out a pelvic examination, unless this is contraindicated

![]() check serum for LH, FSH, prolactin, testosterone, thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

check serum for LH, FSH, prolactin, testosterone, thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

![]() arrange a transvaginal ultrasound scan, looking for polycystic ovaries

arrange a transvaginal ultrasound scan, looking for polycystic ovaries

![]() review with the results (Table 8.3).

review with the results (Table 8.3).

Table 8.3

Further management based on test results

| Ultrasound scan | A scan showing large-volume ovaries (> 10 cm3) and/or multiple small follicles (12 or more < 10 mm) | If pregnancy desired, clomifene or gonadotrophins. If pregnancy not desired, consider the combined oral contraceptive pill |

| Elevated PRL level | If PRL > 1000 mU/L on at least two occasions, the diagnosis is hyperprolactinaemia | Arrange MRI or CT of the pituitary. Treat with dopamine agonist |

| Elevated FSH | If FSH > 30 U/L, repeat 6 weeks later. If still elevated and the patient > 40 years old, the patient is menopausal. If less than 40, the diagnosis is premature ovarian failure | Consider HRT. Pregnancy with oocyte donation is possible |

| Abnormal TFTs | If the TFTs are abnormal, treat as appropriate |

FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; LH, luteinizing hormone; PRL, prolactin; TFTs thyroid function tests.

If the tests listed in Table 8.3 are normal, consider the following causes:

![]() weight loss

weight loss

![]() depression, emotional disturbance and extreme exercise

depression, emotional disturbance and extreme exercise

![]() Asherman syndrome

Asherman syndrome

![]() idiopathic amenorrhoea.

idiopathic amenorrhoea.

In the majority of patients who present with secondary amenorrhoea, investigations will fail to demonstrate any significant endocrine abnormality – idiopathic amenorrhoea. It is probable that there is a disturbance of the normal feedback mechanisms of control. Undue sensitivity of the hypothalamus and pituitary to the negative feedback suppression of endogenous oestrogen may result in impaired gonadotrophin secretion which is inadequate to stimulate follicular development, and results in cycle initiation failure. Those requiring ovulation usually respond well to an anti-oestrogen such as clomifene.