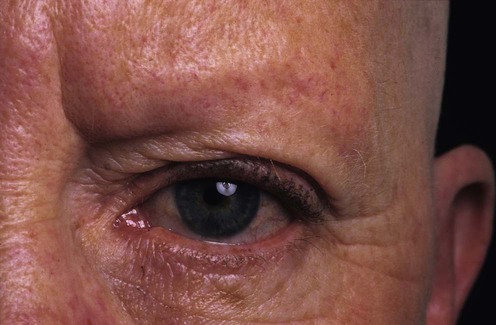

Alopecia areata

First-Line therapies

Second-Line therapies

Lack of efficacy of topical latanoprost and bimatoprost ophthalmic solutions in promoting eyelash growth in patients with alopecia areata.

Roseborough I, Lee H, Chwalek J, Stamper RL, Price VH. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60: 705–6.

A controlled trial of 16 weeks duration with 11 patients did not confirm any response.

Another small trial of similar design has also shown the same negative result.

Third-Line therapies

Intralesional steroids

Intralesional steroids Topical immunotherapy

Topical immunotherapy Topical corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids Anthralin/dithranol

Anthralin/dithranol Retinoic acid

Retinoic acid Topical minoxidil

Topical minoxidil Bimatoprost / Latanoprost eye drops (for eyelashes)

Bimatoprost / Latanoprost eye drops (for eyelashes) PUVA

PUVA Systemic corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids Systemic cyclosporine

Systemic cyclosporine Oral minoxidil

Oral minoxidil Sulphasalazine

Sulphasalazine Methotrexate

Methotrexate Azathioprine

Azathioprine Inosiplex (inosine pranobex)

Inosiplex (inosine pranobex) Nitrogen mustard

Nitrogen mustard Dermatography

Dermatography Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy Pulsed infrared diode laser

Pulsed infrared diode laser Excimer laser

Excimer laser Topical bexarotene

Topical bexarotene Topical azelaic acid

Topical azelaic acid Combination treatment of simvastatin and ezetimibe

Combination treatment of simvastatin and ezetimibe Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy Onion juice

Onion juice Combination of topical garlic gel and topical betamethasone valerate

Combination of topical garlic gel and topical betamethasone valerate