Allergy

Paediatric allergy

• In the UK up to 40% of children have allergic rhinitis, eczema or asthma and up to 6% develop food allergy

• They are increasing in prevalence in many countries

• They are the commonest chronic diseases of childhood and the commonest cause of school absence and acute hospital admissions

• They cause significant morbidity and can be fatal, with about 20 children dying from asthma and 2 from food anaphylaxis in the UK each year.

Explanations of some of the terms used in ‘allergy’ are listed in Box 15.1.

Mechanisms of allergic disease

Only a few stimuli account for most allergic disease:

• Inhalant allergens, e.g. house-dust mite, plant pollens, pet dander and moulds in asthma and rhinitis and conjunctivitis

• Ingestant allergens, e.g. nuts, seeds, legumes, cow’s milk, egg, seafood and fruits in acute allergic reactions or eczema

• An early phase, occurring within minutes of exposure to the allergen, caused by release of histamine and other mediators from mast cells. Causes urticaria, angioedema, sneezing and bronchospasm

• A late phase response may also occur after 4–6 hours. This causes nasal congestion in the upper airway, and cough and bronchospasm in the lower airway.

The majority of severe life-threatening allergic reactions are IgE mediated.

The hygiene hypothesis

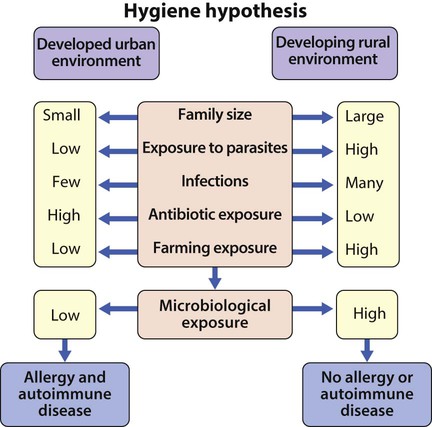

It is not clear why the prevalence of allergic diseases has increased in many countries and the speed of this change suggests an environmental cause. A consistent observation is that the risk is lower in younger children of large families and in children raised on farms. These findings have led to the hygiene hypothesis, which proposes that the increased prevalence is due to altered microbial exposure associated with modern living conditions (Fig. 15.1). Although the hypothesis remains the leading explanation for the increase in allergic disease, it is mainly supported by indirect evidence.

The allergic march

Allergic children develop individual allergic disorders at different ages:

• Eczema and food allergy usually develop in infancy; both are often present

• Allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis and asthma occur most often in preschool and primary school years

• Rhinitis and conjunctivitis often precede the development of asthma, and in children with asthma, up to 80% have coexistent rhinitis.

Prevention of allergic diseases

History and examination

• Mouth breathing (Fig. 15.2a). Children who habitually breathe with their mouth open may have an obstructed nasal airway from rhinitis, and there may also be a history of snoring or obstructive sleep apnoea

• An allergic salute (Fig. 15.2b), from rubbing an itchy nose

• Pale and swollen inferior nasal turbinates

• Hyperinflated chest or Harrison sulci from chronic undertreated asthma

• Atopic eczema affecting the limb flexures

• Allergic conjunctivitis; may also be prominent creases (Dennie-Morgan folds) and blue-grey discoloration below the lower eyelids.

Food allergy and food intolerance

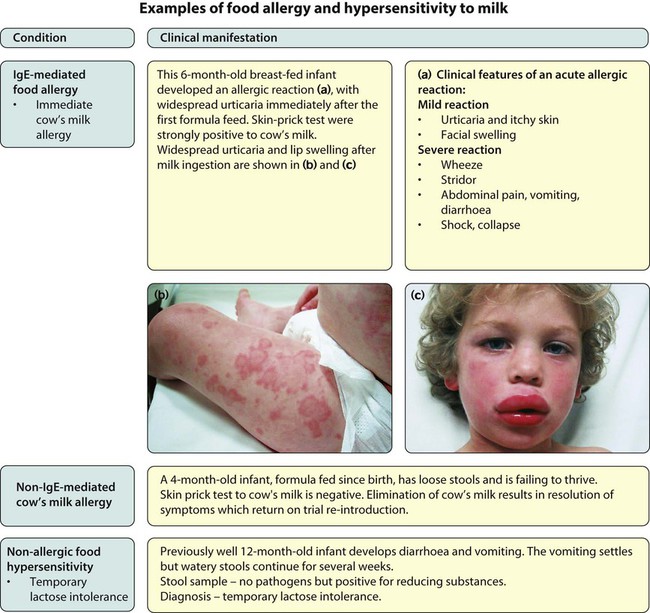

A food allergy occurs when a pathological immune response is mounted against a specific food protein. It is usually IgE mediated, but may be non-IgE mediated. A non-immunological hypersensitivity reaction to a specific food is called food intolerance. An example of each in relation to cow’s milk is shown in Figure 15.3.

• In infants, the most common causes are milk, egg and peanut

• In older children, peanut, tree nut and fish and shellfish.

Diagnosis

The most helpful screening tests for IgE-mediated food allergy are skin-prick tests (Fig. 15.4) and measurement of specific IgE antibodies in blood (RAST test). Both tests may yield false-positive results, but the greater the response, the more likely the child is to be allergic. Negative skin test results make IgE-mediated allergy unlikely.

Eczema

Eczema is classified as atopic (where there is evidence of IgE antibodies to common allergens) or non-atopic. Atopic eczema is classified as an allergic disease as many affected children will have a family history of allergy, at least 50% develop other allergic diseases and IgE antibodies to common allergens are present. There is a close relationship between eczema and food allergy, particularly in young infants with severe disease; up to 40% of them have an IgE-mediated food allergy, in particular egg allergy. Screening by skin prick or IgE blood testing should be considered. The condition is described in Chapter 24.

Allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis (rhinoconjunctivitis)

This can be atopic (associated with IgE antibodies to common inhalant allergens) or non-atopic. It is an underestimated cause of childhood morbidity. The disease can be classified as intermittent or persistent and mild or severe, although in temperate climates it is often classified as seasonal (related to seasonal grass, weed or tree pollens) and perennial (related to perennial allergens such as house-dust mite and pets). It affects up to 20% of children and can severely disrupt their lives. In addition to its classic presentation of coryza and conjunctivitis, it can also present as ‘cough-variant rhinitis’ due to a post-nasal drip, and as a chronically blocked nose causing sleep disturbance and impaired daytime behaviour and concentration, or with predominant eye symptoms. It is associated with eczema, sinusitis and adenoidal hypertrophy and is closely associated with asthma. Treatment of allergic rhinitis may improve the control of coexistent asthma. Treatment options are listed in Box 15.2.

Asthma

Allergy is an important component of asthma. Affected children often have IgE antibodies to aeroallergens (house-dust mite; tree, grass and weed pollens; moulds; animal danders). Allergen avoidance is difficult to achieve. Management of asthma is described in Chapter 16 on Respiratory disorders.

Urticaria and angioedema

Chronic urticaria (persisting >6 weeks) is usually non-allergic in origin. It results from a local increase in the permeability of capillaries and venules. These changes are dependent on activation of skin mast cells, which contain a range of mediators including histamine. A classification of urticaria is shown in Box 15.3. Treatment is with second-generation non-sedating antihistamines.