20 Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Dependence

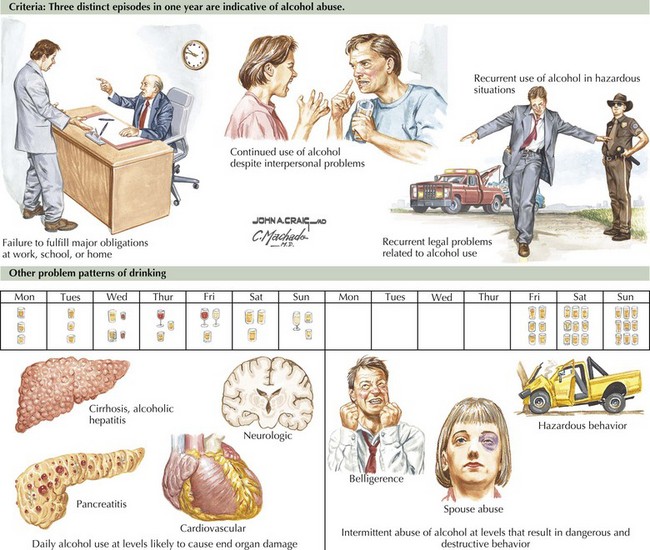

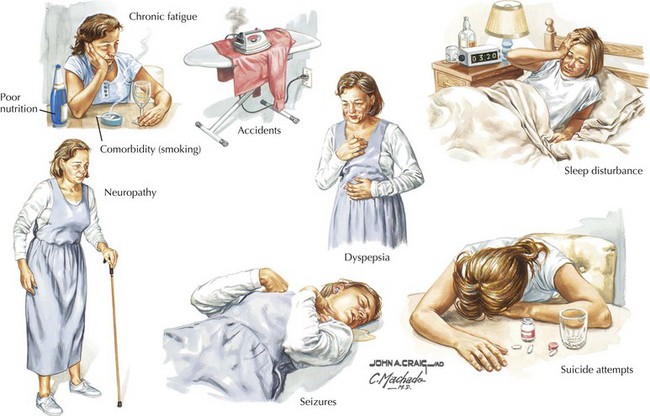

Most physicians are intimately familiar with the protean manifestations of alcohol abuse and dependence (Fig. 20-1) and its characteristic clinical signs (Fig. 20-2). Incidence rates vary widely between cultural groups (alcoholism is almost unheard of in traditional Muslim communities), but lifetime rates of 5–10% are the rule in North America and Europe. Therefore, physicians who state that they never see alcoholism may not be recognizing the diagnosis. Patient denial significantly contributes to overlooking this potential diagnosis. This denial has several sources. Admitting to a problem with alcohol or other drugs may be humiliating for patients. Furthermore, alcohol use, even at dangerous levels, is a culturally embedded and approved, often pleasurable part of social life.

Clinical Presentation

Alcohol has direct toxic effects on multiple tissues, including the central nervous system, liver, the pancreas, and the heart. Patients may present with acute or chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, esophageal varices, cardiomyopathy, and dementia. Acute withdrawal syndromes occur occasionally, leading to delirium tremens, Wernicke encephalopathy, and Korsakoff psychosis, as illustrated in Chapter 17.

Diagnosis

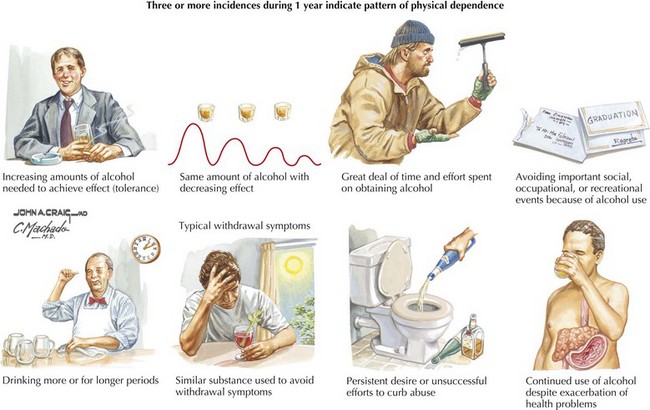

To avoid missing the diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence, physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion directed at eliciting classic historic signs of impending alcohol abuse (Fig. 20-2). Similarly, asking about features suggestive of early alcohol dependence is equally important during what needs to be routine screening for alcoholism in any patient (Fig. 20-3). Asking about average levels and patterns of alcohol use should be part of every examination. Because patients underestimate their consumption, a useful rule of thumb is to double the amount reported by the patient. Patients also need to be questioned about binge drinking, withdrawal signs, blackouts, and excessive tolerance. The four-question CAGE questionnaire is a good screening instrument (Box 20-1). One positive answer to a CAGE question is cause for concern; two positive answers corresponds to a 50% risk of alcoholism.

Treatment

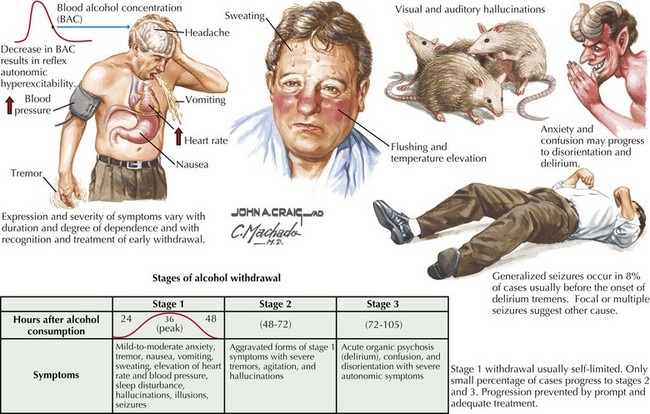

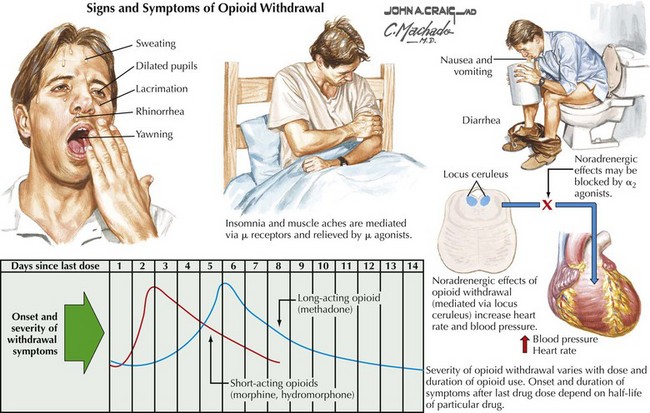

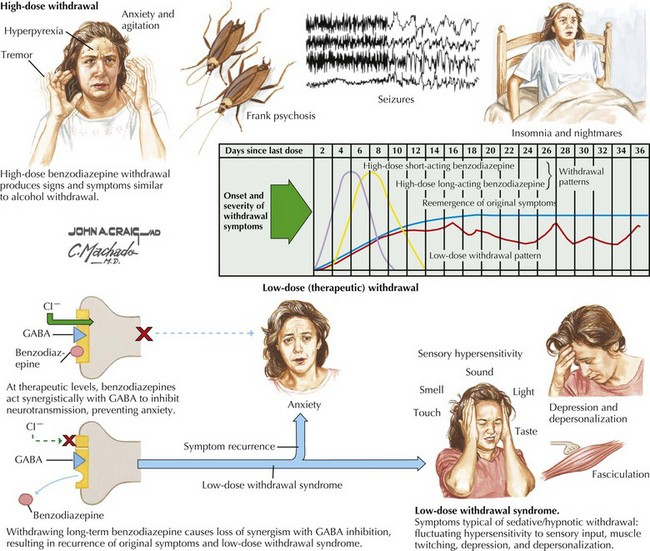

Withdrawal from alcohol and other cross-tolerant sedative hypnotics (barbiturates, benzodiazepines, methaqualone, etc.) is potentially hazardous (Figs. 20-4 to 20-6). This can lead to agitated delirium and seizures. In contrast, most other pharmacologic withdrawals are characterized by dysphoria but are not medically dangerous; nevertheless, withdrawal from cocaine and amphetamines can lead to a profound depression.

Hays JT. Efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation. Am J Med. 2008 Apr;121(4 Suppl. 1):S32-S42.

Johnson BA, et al. Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007 Oct 10;298(14):1641-1651.

Karila L, et al. New treatments for cocaine dependence: a focused review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008 May;11(3):425-438.

Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997 Jan-Feb;4(5):231-244.

Krupitsky EM. Antiglutamatergic strategies for ethanol detoxification: comparison with placebo and diazepam. Alcohol. 2007 Apr;31(4):604-611.

Spanagel R, Kiefer F. Drugs for relapse prevention of alcoholism: ten years of progress. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008 Mar;29(3):109-115.