Chapter 11 Agnosias

Visual Agnosias

Cortical Visual Disturbances

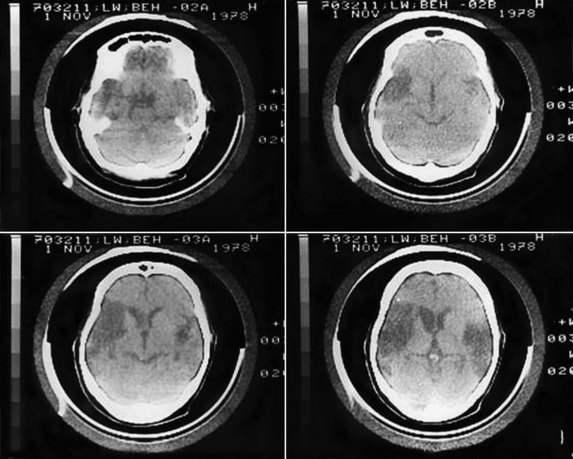

Patients with bilateral occipital lobe damage may have complete “cortical” blindness. Some patients with cortical blindness are unaware that they cannot see, and some even confabulate visual descriptions or blame their poor vision on dim lighting or not having their glasses (Anton syndrome, originally described in 1899). Patients with Anton syndrome may describe objects they “see” in the room around them but walk immediately into the wall. The phenomena of this syndrome suggest that the thinking and speaking areas of the brain are not consciously aware of the lack of input from visual centers. Anton syndrome can still be thought of as a perceptual deficit rather than a visual agnosia, but one in which there is unawareness or neglect of the sensory deficit. Such visual unawareness is also frequently seen with hemianopic visual field defects (e.g., in patients with R hemisphere strokes), and it even has a correlate in normal people; we are not conscious of a visual field defect behind our heads, yet we know to turn when we hear a noise from behind. In contrast to Anton syndrome, some cortically blind patients actually have preserved ability to react to visual stimuli, despite the lack of any conscious visual perception, a phenomenon termed blindsight or inverse Anton syndrome (Ro and Rafal, 2006). Blindsight may be considered an agnosic deficit, because the patient fails to recognize what he or she sees. Residual vision is usually absent in blindness caused by disorders of the eyes, optic nerves, or optic tracts. Patients with cortical vision loss may react to more elementary visual stimuli such as brightness, size, and movement, whereas they cannot perceive finer attributes such as shape, color, and depth. Subjects sometimes look toward objects they cannot consciously see. One study reported a woman with postanoxic cortical blindness who could catch a ball without awareness of seeing it. Blindsight may be mediated by subcortical connections such as those from the optic tracts to the midbrain.

Lesions causing cortical blindness may also be accompanied by visual hallucinations. Irritative lesions of the visual cortex produce unformed hallucinations of lines or spots, whereas those of the temporal lobes produce formed visual images. Visual hallucinations in blindness are referred to as Bonnet syndrome (Teunisse et al., 1996). Although Bonnet originally described this phenomenon in his grandfather, who had ocular blindness, complex visual hallucinations occur more typically with cortical visual loss (Manford and Andermann, 1998). Visual hallucinations can occur during recovery from cortical blindness; positron emission tomography (PET) has shown metabolic activation in the parieto-occipital cortex associated with hallucinations, suggesting hyperexcitability of the recovering visual cortex (Wunderlich et al., 2000).

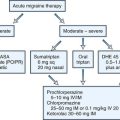

In practice, we diagnose cortical blindness by the absence of ocular pathology, the preservation of the pupillary light reflexes, and the presence of associated neurological symptoms and signs. In addition to blindness, patients with bilateral posterior hemisphere lesions are often confused, agitated, and have short-term memory loss. Amnesia is especially common in patients with bilateral strokes within the posterior cerebral artery territory, which involves not only the occipital lobe but also the hippocampi and related structures of the medial temporal region. Cortical blindness occurs as a transient phenomenon after traumatic brain injury, in migraine, in epileptic seizures, and as a complication of iodinated contrast procedures such as arteriography. Cortical blindness can develop in the setting of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (Wunderlich et al., 2000), meningitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dementing conditions such as the Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, or the posterior cortical atrophy syndrome described in Alzheimer disease and other dementias (Kirshner and Lavin, 2006).

Balint Syndrome and Simultanagnosia

In 1909, Balint described a syndrome in which patients act blind, yet can describe small details of objects in central vision (Rizzo and Vecera, 2002). The disorder is usually associated with bilateral hemisphere lesions, often involving the parietal and frontal lobes. Balint syndrome involves a triad of deficits: (1) psychic paralysis of gaze, also called ocular motor apraxia, or difficulty directing the eyes away from central fixation; (2) optic ataxia, or incoordination of extremity movement under visual control (with normal coordination under proprioceptive control; and (3) impaired visual attention. These deficits result in the perception of only small details of a visual scene, with loss of the ability to scan and perceive the “big picture.” Patients with Balint syndrome literally cannot see the forest for the trees. Some but not all patients have bilateral visual field deficits. In bedside neurological examination, helpful tests include asking the patient to interpret a complex drawing or photograph, such as the “Cookie Theft” picture from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Partial deficits related to Balint syndrome have also been described, including isolated optic ataxia, or impaired visually guided reaching toward an object. Optic ataxia likely results from disruption of the transmission of visual information for visual direction of motor acts from the occipital cortex to the premotor areas. This function involves portions of the dorsal occipital and parietal areas as part of the “dorsal visual stream” (Himmelbach et al., 2009). A second partial Balint syndrome deficit is simultanagnosia, or loss of ability to perceive more than one item at a time, first described by Wolpert in 1924. The patient sees details of pictures, but not the whole. Many such patients have left occipital lesions and associated pure alexia without agraphia; these patients can often read “letter-by-letter,” or one letter at a time, but they cannot recognize a word at a glance (see Chapter 12). Robertson and colleagues (1997) emphasized deficient spatial organization as a contributing factor to the perceptual difficulties of a patient with Balint syndrome secondary to bilateral parieto-occipital strokes. Balint syndrome has also been reported in patients with posterior cortical atrophy and related neurodegenerative conditions involving the posterior parts of both hemispheres (Kirshner and Lavin, 2006; McMonagle et al., 2006).

Visual Object Agnosia

Visual object agnosia is the quintessential visual agnosia: the patient fails to recognize objects by sight, with preserved ability to recognize them through touch or hearing in the absence of impaired primary visual perception or dementia (Biran and Coslett, 2003). In 1890, Lissauer distinguished two subtypes of visual object agnosia: apperceptive visual object agnosia, referring to the synthesis of elementary perceptual elements into a unified image, and associative visual object agnosia, in which the meaning of a perceived stimulus is appreciated by recall of previous visual experiences.

Apperceptive Visual Agnosia

The first type, apperceptive visual agnosia, is difficult to separate from impaired perception or partial cortical blindness. Patients with apperceptive visual agnosia can pick out features of an object correctly (e.g., lines, angles, colors, movement), but they fail to appreciate the whole object (Grossman et al., 1997).Warrington and Rudge (1995) pointed to the right parietal cortex for its importance in visual processing of objects, and they found this area critical to apperceptive visual agnosia. A patient described by Luria misnamed eyeglasses as a bicycle, pointing to the two circles and a crossbar. Another study considered apperceptive visual agnosia related to bilateral occipital lesions a “pseudoagnosic syndrome” associated with visual processing defects, as compared to true visual agnosias, in which the right parietal cortex is deficient in identifying and recognizing visual objects. Recent evidence of the functions of specific cortical areas has included the specialization of the medial occipital cortex for appreciation of color and texture, whereas the lateral occipital cortex is more involved with shape perception. Deficits in these specific visual functions can be seen in patients with visual object agnosia (Cavina-Pratesi et al., 2010). On the other hand, a patient reported by Karnath et al. (2009) had visual form agnosia with bilateral medial occipitotemporal lesions.

Another way of analyzing apperceptive visual agnosia is by the focusing of visual attention. Theiss and DeBleser in 1992 distinguished two features of visual attention: a wide-angle attentional lens that sees the figure generally but perceives only gross features (the forest), and a narrow-angle spotlight that focuses on the fine visual details (the trees). They described a patient with a faulty wide-angle attentional beam; she could identify small objects within a drawing but missed what the drawing represented. Fink and colleagues (1996), in PET studies of visual perception in normal subjects, found that right hemisphere sites, particularly the lingual gyrus, activated during global processing of figures, whereas left hemisphere sites, particularly the left inferior occipital cortex, activated during more local processing. The ability of patients with apperceptive visual agnosia to perceive fine details but not the whole picture (missing the forest for the trees) is closely related to Balint syndrome and simultanagnosia.

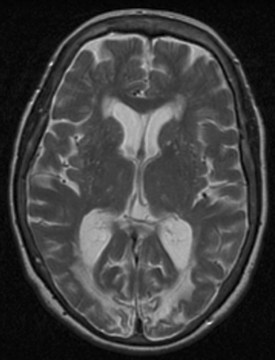

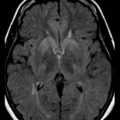

As with most cortical visual syndromes, apperceptive visual agnosia usually occurs in patients with bilateral occipital lesions. It may represent a stage in recovery from complete cortical blindness. Deficits in recognition of visual objects may be especially apparent with recognition of degraded images, such as drawings rather than actual objects. Apperceptive visual agnosia can also be part of dementing syndromes (Kirshner and Lavin, 2006; McMonagle et al., 2006) (Fig. 11.1).

Prosopagnosia

Facial recognition is a complex function. First, patients who cannot match pictures of faces must have defective face processing, or apperceptive prosopagnosia, whereas those who can match faces but simply fail to recognize familiar examples (either friends and relatives or famous personages) have associative prosopagnosia (Barton et al., 2004). There has been some opinion that faces are not a unique perceptual entity but just representative of complex stimuli, but a recent study by Busigny and colleagues (2010) found that their patient performed normally in perceptual tasks involving cars, objects, and geometric shapes, while deficient with faces. Another aspect of facial recognition is the perception of emotion in facial expressions, a function that appears localized to the right hemisphere. A recent study suggested that white matter lesions disconnecting the occipital cortex from “emotion-related regions” might be responsible for agnosia for emotional facial expression (Philippi et al., 2009).

In clinical studies, prosopagnosia may occur either as an isolated deficit or as part of a more general visual agnosia for objects and colors. Faces are likely the most complex and individualized visual displays to recognize, but some patients with visual object agnosia can recognize faces, suggesting that there may be a specific brain area devoted to facial recognition. Humphreys (1996) reviewed evidence that living things may be recognized in a different part of the occipital cortex from nonliving things.

The anatomical localization of prosopagnosia parallels that of the other visual agnosias. Most studies have reported bilateral temporo-occipital lesions, often involving the fusiform or occipitotemporal gyri, but cases with unilateral posterior right hemisphere lesions have also been described. Facial perception seems localized to the fusiform gyri, but recognition of familiar faces may require anterior temporal memory stores (Barton, 2003). A recent study involving both functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and neuropsychological testing found the inferior occipital (“occipital face area”) lobe critical for the identification of specific individual faces, whereas the “fusiform face area” in the middle fusiform gyrus was involved in other aspects of face perception (Steeves et al., 2009). The disconnection hypothesis has been invoked in prosopagnosia, reflecting interruption of fibers passing from the occipital cortices to the centers where memories of faces are stored. Prosopagnosia also occurs in dementing illnesses such as frontotemporal dementia (Joubert et al., 2004) and posterior cortical atrophy (Kirshner and Lavin, 2006).

Klüver-Bucy Syndrome

Another form of visual agnosia is the psychic blindness syndrome described by Klüver and Bucy in 1939. They reported the syndrome originally in monkeys with bilateral temporal lobectomies, but similar symptoms develop in humans with bilateral temporal lesions (Trimble et al., 1997). An animal may inappropriately try to eat or mate with objects or fail to show customary fear when confronted with a natural enemy. Human Klüver-Bucy patients manifest visual agnosia and prosopagnosia as well as memory loss, language deficits, and changes in behavior such as placidity, altered sexual orientation, and excessive eating. Cases of the human Klüver-Bucy syndrome have been reported with bitemporal damage from surgical ablation, herpes simplex encephalitis, and dementing conditions such as Pick disease. Patients with Klüver-Bucy syndrome appear to have no major deficits of primary visual perception, but connections appear to be disrupted between vision and memory and limbic structures, so visual percepts do not arouse their ordinary associations.

Auditory Agnosias

Cortical Deafness

A patient with auditory agnosia can hear noises but not appreciate their meanings, as in identifying animal cries or sounds associated with specific objects, such as the ringing of a bell. Most such patients also cannot understand speech or appreciate music. Auditory agnosias can be divided into (1) pure word deafness, (2) pure auditory nonverbal agnosia, (3) phonagnosia, or inability to identify persons by their voices (Polster and Rose, 1998; Hailstone et al., 2010), and (4) pure amusia. Patients may have one or a mixture of these deficits.

Pure Word Deafness

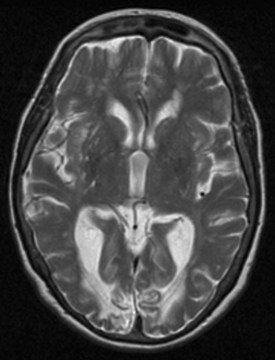

The syndrome of pure word deafness involves an inability to comprehend spoken words, with preserved ability to hear and recognize nonverbal sounds. Pure word deafness often evolves out of an initial deficit of cortical deafness or severe cortical auditory disorder. Pure word deafness has traditionally been explained as a disconnection of both primary auditory cortices from the left hemisphere Wernicke area. Engelien and colleagues (2000) showed activation on PET scanning during auditory stimulation in a patient with extensive bilateral temporal lesions, a phenomenon they referred to as deaf hearing (analogous to blindsight). Unilateral left hemisphere lesions have also been associated with pure word deafness; by Geschwind’s disconnection theory, such a lesion might be strategically placed so as to disconnect both primary auditory cortices from the Wernicke area. Occasionally patients with Wernicke aphasia have more severe involvement of auditory comprehension than reading comprehension, also resembling pure word deafness. In fact, most cases of pure word deafness also have paraphasic speech, further linking the syndrome to Wernicke aphasia (Fig. 11.2).

Auditory Nonverbal Agnosia

Auditory nonverbal agnosia refers to patients who have lost the ability to identify meaningful nonverbal sounds but have preserved pure tone hearing and language comprehension. These cases also tend to have bilateral temporal lobe lesions. A recently reported case had a unilateral left temporal lesion with evidence of reorganization of auditory word perception involving adjacent left and contralateral right temporal cortex (Saygin et al., 2010).

Phonagnosia

Phonagnosia is analogous to prosopagnosia in the visual modality; it is a failure to recognize familiar people by their voices. Again, apperceptive deficits can occur in the matching of unfamiliar voices, usually reflecting unilateral or bilateral temporal damage, but failure to recognize a familiar voice may involve a right parietal locus corresponding to the specific area for recognition of faces. A related deficit is auditory affective agnosia, or failure to recognize the emotional intonation of speech, usually associated with right hemisphere lesions (Polster and Rose, 1998). Two cases of progressive phonagnosia have been reported in frontotemporal dementia (Hailstone et al., 2010).

Amusia

The loss of musical abilities after focal brain lesions is another complex topic, reflecting the complexity of musical appreciation and analysis (Alossa and Castelli, 2009). Traditional lesion-deficit analysis has suggested that recognition of melodies and musical tones is a right temporal function, whereas analysis of pitch, rhythm, and tempo involves the left temporal lobe. In a recent study of patients with temporal lobe lesions and epilepsy, those with left hemisphere lesions were more impaired in temporal sequencing of music as well as speech (Samson et al., 2001). The left hemisphere is likely more activated when a trained musician listens to music, as compared to an untrained listener. In a study of PET brain imaging during musical performance in 10 professional pianists, sight-reading of music activated both visual association cortices and the superior parietal lobes, areas distinct from those utilized in reading words. Listening to music activated both secondary auditory cortices, and playing music activated frontal and cerebellar areas. The authors commented that widespread as these areas were, the study did not examine the whole of musical experience, let alone the pleasure afforded by music.

Tactile Agnosias

As we have seen with the syndromes of cortical loss of visual and auditory perception, a range of somatosensory deficits is seen with cortical lesions. Patients with lesions of the parietal cortex may have preserved ability to feel pinprick, temperature, vibration, and proprioception, yet they fail to identify objects palpated by the contralateral hand or to recognize numbers or letters written on the opposite side of the body. These deficits, called astereognosis and agraphesthesia, represent deficits of cortical sensory loss rather than agnosias. Alternatively, they could be considered as apperceptive tactile agnosias. Rarely patients have been reported who can describe the shape and features of a palpated object, yet cannot identify the object. The patient can readily identify the object by sound or sight, thereby fulfilling the criteria for associative tactile agnosia (Bottini et al., 1995).

The mechanisms of tactile agnosia may vary. First, appreciation of shape may be a property of the sensory cortex. In the studies of Bottini and colleagues (1995), matching of shapes (an apperceptive task) was more sensitive to right hemisphere damage, whereas matching of meaningful shapes (the associative task) was more sensitive to left hemisphere lesions. Second, the right parietal cortex is also involved in spatial and topographical functions, and spatial disorders may account for some of the tactile recognition deficits of patients with right parietal lesions. Third, attentional deficits and neglect seen with right hemisphere lesions may increase the lack of tactile recognition. Fourth, disconnection syndromes may be involved in tactile agnosia. The famous 1962 patient of Geschwind and Kaplan with a lesion of the corpus callosum could not identify objects with the left hand but could point to the correct object in a group. Patients with surgical section of the corpus callosum have similar deficits; these patients can feel the object with the left hand but cannot name it, presumably because the callosal lesion disconnects the right parietal cortex from left hemisphere language centers.

Alossa N., Castelli L. Amusia and musical functioning. Eur Neurol. 2009;61:269-277.

Barton J. Disorders of face perception and recognition. Neurol Clin. 2003;21:521-548.

Barton J.J., Cherkasova M.V., Hefter R. The covert priming effect of faces in prosopagnosia. Neurology. 2004;63:2062-2068.

Biran I., Coslett H.B. Visual agnosia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2003;3:508-512.

Bottini G., Cappa S.F., Sterzi R., et al. Intramodal somaesthetic recognition disorders following right and left hemisphere damage. Brain. 1995;118:395-399.

Busigny T., Graf M., Mayer E., et al. Acquired prosopagnosia as a face-specific disorder: ruling out the general visual similarity account. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:2051-2067.

Cavina-Pratesi C., Kentridge R.W., Heywood C.A., et al. Separate processing of texture and form in the ventral stream: evidence from FMRI and visual agnosia. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:433-446.

Engelien A., Huber W., Silbersweig D., et al. The neural correlates of “deaf-hearing” in man: conscious sensory awareness enabled by attentional modulation. Brain. 2000;123:532-545.

Fink G.R., Halligan P.W., Marshall J.C., et al. Where in the brain does visual attention select the forest and the trees? Nature. 1996;82:626-628.

Grossman M., Galetta S., D’Esposito M. Object recognition difficulty in visual apperceptive agnosia. Brain Cogn. 1997;33:306-342.

Hailstone J.C., Crutch S.J., Vestergaard M.D., et al. Progressive associative phonagnosia: a neuropsychological analysis. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:1104-1114.

Himmelbach M., Nau M., Zundorf I., et al. Brain activation during immediate and delayed reaching in optic ataxia. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:1508-1517.

Humphreys G.W. Object recognition: the man who mistook his dog for a cat. Curr Biol. 1996;6:821-824.

Joubert S., Felician O., Barbeau E., et al. Progressive prosopagnosia: clinical and neuroimaging results. Neurology. 2004;63:1962-1965.

Karnath H.O., Ruter J., Mandler A., et al. The anatomy of object recognition—visual form agnosia caused by medial occipitotemporal stroke. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11421-11423.

Kirshner H.S., Lavin P.J. Posterior cortical atrophy: a brief review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6:477-480.

Manford M., Andermann F. Complex visual hallucinations. Clinical and neurobiological insights. Brain. 1998;121:1819-1840.

McMonagle P., Deering F., Berliner Y., et al. The cognitive profile of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2006;66:331-338.

Philippi C.L., Mehta S., Grabowski T., et al. Damage to association fiber tracts impairs recognition of the facial expression of emotion. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15089-15099.

Polster M.R., Rose S.B. Disorders of auditory processing: evidence for modularity in audition. Cortex. 1998;34:47-65.

Rizzo M., Vecera S.P. Psychoanatomical substrates of Balint’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:161-178.

Ro T., Rafal R. Visual restoration in cortical blindness: insights from natural and TMS-induced blindsight. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2006;16:377-396.

Robertson L., Treisman A., Friedman-Hill S.R., et al. The interaction of spatial and object pathways: evidence from Balint’s syndrome. J Cogn Neurosci. 1997;9:295-317.

Samson S., Ehrle N., Baulac M. Cerebral substrates for musical temporal processes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;930:166-178.

Saygin A.P., Leech R., Dick F. Nonverbal auditory agnosia with lesion to Wernicke’s area. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:107-113.

Steeves J., Dricot L., Goltz H.C., et al. Abnormal face identity coding in the middle fusiform gyrus of two brain-damaged prosopagnosic patients. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2584-2592.

Teunisse R.J., Cruysberg J.R., Hoefnagels W.H., et al. Visual hallucinations in psychologically normal people. Charles Bonnet’s syndrome. Lancet. 1996;347:794-797.

Trimble M.R., Mendez M.F., Cummings J.L. Neuropsychiatric symptoms from the temporolimbic lobes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:429-438.

Warrington E.K., Rudge P. A comment on apperceptive agnosia. Brain Cogn. 1995;28:173-177.

Wunderlich G., Suchan B., Volkmann J., et al. Visual hallucinations in recovery from cortical blindness. Imaging correlates. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:561-565.