Chapter 39 Adrenocorticosteroids

| Abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| AVP | Arginine vasopressin |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CRH | Corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| GR | Glucocorticoid receptor |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal |

| MR | Mineralocorticoid receptor |

| MSH | Melanocyte-stimulating hormone |

| POMC | Proopiomelanocorticotropin |

| StAR | Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein |

| t1/2 | half-life |

Therapeutic Overview

| Therapeutic Overview |

|---|

| Glucocorticoids |

| Replacement therapy in adrenal insufficiencies |

| Antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive action |

| Myeloproliferative diseases |

| Mineralocorticoids |

| Replacement therapy in primary adrenal insufficiencies |

| Hypoaldosteronism |

| Steroid Synthesis Inhibitors |

| Adrenocortical hyperfunction |

| Steroid Receptor Blockers |

| Glucocorticoid excess |

| Mineralocorticoid excess |

glucocorticoids, a withdrawal plan must be instituted, or serious morbidity and even mortality may occur. Safe removal from dependence on exogenous glucocorticoids requires systematic and gradual lowering of the administered dosage, which may require up to a year for the natural secretion of cortisol to recover. Also, during periods of emotional or physiological stress, such patients may require glucocorticoid supplementation.

Mechanisms of Action

The biosynthetic pathways and structures for cortisol and aldosterone are shown in Figures 38-1 and 38-2.

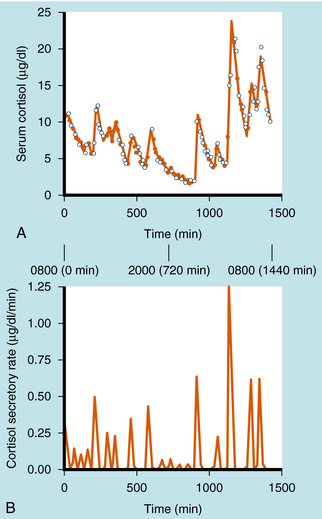

Cortisol synthesis and secretion are regulated physiologically by ACTH synthesized in the anterior pituitary. ACTH is synthesized in the corticotrope cells of the anterior pituitary as part of the large precursor molecule proopiomelanocorticotropin (POMC), which is proteolytically cleaved to form ACTH, β-endorphin, and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH). β-Endorphin has opioid effects that reduce pain perception (see Chapter 36), whereas MSH acts on the melanocytes that confer skin pigmentation. The hyperpigmentation that is associated with overproduction of ACTH is thought to be associated with overproduction of MSH. The POMC gene is also transcribed in the posterior pituitary, where the POMC precursor is differentially cleaved into endorphins and MSH, but not ACTH. ACTH is secreted episodically from the anterior pituitary, and these pulses can contribute to the larger ACTH fluctuations regulated by circadian rhythms. Generally, the ACTH pulses exhibit greater frequency and magnitude in the early morning compared with the early afternoon. There is a close correlation of ACTH and cortisol secretion, which is characterized by a sharp rise in plasma concentrations followed by a slower decline, with approximately 8 to 10 major bursts of cortisol secretion occurring daily (Fig. 39-1).

The rate-limiting enzyme in steroid synthesis converts cholesterol to pregnenolone by the P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (see Fig. 38-1), desmolase, located on the inner mitochondrial membrane. ACTH-stimulated increases in cAMP accelerate transcription rates of the gene coding for this enzyme and most other enzymes in the cortisol biosynthetic pathway.

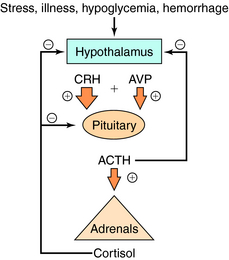

Serum concentrations of ACTH are modulated by integrated stimulatory signals from hypothalamic releasing peptides and by inhibitory feedback from circulating cortisol (Fig. 39-2). Physiologically, serum ACTH concentrations are increased in response to metabolic stresses such as severe trauma, illness, burns, hypoglycemia, hemorrhage, fever, exercise, and psychological stresses such as anxiety and depression. These stresses are believed to induce physiological changes by altering the release of hypothalamic factors. Two hypothalamic peptides, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and to a lesser extent arginine vasopressin (AVP or antidiuretic hormone), both act to stimulate ACTH release. These peptides bind to distinct membrane receptors on the corticotrope. CRH exerts its effect primarily via cAMP-dependent pathways, whereas AVP stimulates phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis and activates protein kinase C. CRH is the most important physiological stimulating factor and can be used pharmacologically to screen for appropriate corticotrope function. CRH may also increase POMC gene transcription and processing, thus increasing available peptide stores for subsequent release.

All natural and synthetic glucocorticoids act by binding to specific receptors that are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Glucocorticoids bind to both glucocorticoid receptors (GR, also known as NR3C1) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR, also known as NR3C2). These receptors are closely related in their overall DNA sequence but differ considerably in the N-terminal antigenic region of the ligand-binding domains. Both receptors have similar binding affinities for glucocorticoids and are expressed in many cell types including liver, muscle, adipose tissue, bone, lymphocytes, and pituitary. The receptors are proteins consisting of approximately 800 amino acids, which can be divided into functional domains similar to those for other steroid receptors (see Chapter 1). The structure of the steroid receptor is characterized by zinc finger domains formed by stabilization of protein folds by zinc interaction with cysteine residues. In the cytoplasm the inactive steroid receptor exists as a heteromer associated with cytoplasmic proteins (e.g., heat shock protein 90). The interaction of this complex with a steroid leads to dissociation of the accessory protein-receptor complex. This sequence of events is generally called glucocorticoid receptor activation. Phosphorylation of the receptor stabilizes a configuration, the nuclear location signal that interacts with importin at nuclear pores and initiates translocation of the hormone-receptor complex across the nuclear membrane. Once inside the nuclear membrane, the steroid-receptor complex interacts at specific palindromic sites on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), termed glucocorticoid-responsive elements. The binding to DNA is stabilized by the interaction of the zinc finger structures with the major groove of DNA, and specificity is partially conferred by the sequence of the palindromic sites. Specificity among different steroids appears to be conferred by the structure of the steroid-occupied receptor, amino acid sequence of the DNA binding region of the receptor protein, especially the Zn fingers, nucleotide sequence of the DNA binding motif and space between half sites, and chromatin architecture of the gene promoter at sites of interaction of bound receptor protein and DNA. The presence of the specific glucocorticoid response elements in the promoter region of specific genes allows steroids to alter transcription (see Chapter 1).

Aldosterone is the major mineralocorticoid produced by the adrenal cortex and acts primarily at the distal portion of the convoluted renal tubule to promote reabsorption of Na+ and the excretion of K+ (see Chapter 21). Adrenal secretion of aldosterone is controlled by the renin-angiotensin system and the circulating concentration of K+. ACTH stimulates aldosterone formation but plays a secondary role in the regulation of aldosterone secretion.

Receptors for mineralocorticoids are expressed both in epithelial tissue such as distal nephrons and in nonepithelial cells including the hippocampus, hypothalamus, cardiomyocytes, adipocytes, and vasculature. Interestingly, both aldosterone and cortisol have a similar affinity for these receptors. Because the level of aldosterone in the circulation is much lower than cortisol, one might expect that the MR would be saturated with cortisol and that it would be difficult for aldosterone to compete for receptor binding. In mineralocorticoid-responsive tissues such as the kidney and vasculature, receptor occupation by cortisol is obviated by the presence of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2, which converts cortisol to the inactive metabolite cortisone; cortisone has a much lower affinity for the MR, permitting aldosterone to compete effectively for MR activation. It is important to note that licorice or related compounds such as carbenoxolone inhibit 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 and can result in inappropriate cortisol activation of the MR, resulting in hypertension. Similarly, a rare genetic syndrome, Apparent Mineralocorticoid Excess, associated with failure of the enzyme complex to function properly leads to salt retention, hypokalemia, and hypertension.

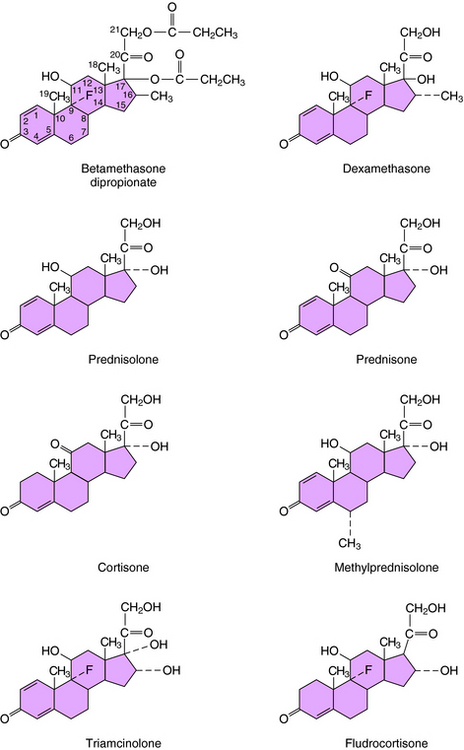

The structures of the principal synthetic glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids are shown in Figure 38-2 Figure 39-3.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic parameters for clinically useful glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids are summarized in Table 39-1. Most glucocorticoids are absorbed rapidly and readily from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract as a result of their lipophilic character. Glucocorticoids are also absorbed readily from the synovial and conjunctival spaces but are absorbed very slowly through the skin. The long-term use of steroids by nasal spray for the control of seasonal rhinitis can lead to nasal and pulmonary epithelial atrophy. Topical administration of glucocorticoids is often used briefly to produce a local action. However, excessive and prolonged local application may result in sufficient absorption to cause systemic effects. The presence of the hydroxyl group at position 11 (see Fig. 38-2) confers glucocorticoid activity on both cortisol and prednisolone. Cortisone and prednisone are 11-ketocorticoids and must be hydroxylated by 11β-hydroxylase to be activated, a reaction that takes place primarily in the liver. Thus the topical application of 11-ketocorticoids on the skin is ineffective, and administration of 11-ketocorticoids should be avoided in patients with abnormal liver function.

| Drugs | Route of Administration | t1/2* |

|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids | ||

| Cortisol (Hydrocortisone) | IM, IV, oral† | Short |

| Cortisone | IM, IV, Oral | Short |

| Prednisone | Oral | Intermediate |

| Prednisolone | IM, IV | Intermediate |

| Methylprednisolone | IM, IV, oral† | Intermediate |

| Dexamethasone | IM, oral,† topical, IV | Long |

| Betamethasone | Oral, topical, inhaled | Long |

| Triamcinolone | Intraarticular, topical, inhaled | Long |

| Mineralocorticoids | ||

| Fludrocortisone | Oral | Intermediate |

| Aldosterone (for reference) | – | Short |

| Desoxycorticosterone acetate | IM | Long |

Principal metabolites of adrenocorticosteroids are steroid glucuronides, which undergo hepatic metabolism and renal excretion.

* Short, 10-90 minutes; intermediate, several hours; long, 5 hours or more.

† Intralesional, intraarticular, nasal, and inhaled; collectively this is referred to as compartmentalized administration.

Addition of a fluorine atom at position 9 and a methyl group at position 16, as present in betamethasone and dexamethasone (see Fig. 39-3), enhances glucocorticoid receptor activation and increases the duration of action of these compounds.

Relationship of Mechanisms of Action to Clinical Response

Glucocorticoids affect glucose, protein, and bone metabolism and possess antiinflammatory and immunosuppressant actions. Glucocorticoids influence the immune system at multiple levels, affecting leukocyte movement, antigen processing, eosinophils, and lymphatic tissues (Box 39-1).

Within hours after administration of glucocorticoids, the number of circulating neutrophils increases. This neutrophilia may result from a glucocorticoid-induced decrease in neutrophil adherence to the vascular endothelium and the inability of neutrophils to egress toward bone marrow or inflammatory sites. In addition, glucocorticoids inhibit antigen processing by macrophages, suppress T-cell helper function, inhibit synthesis of mediators of the inflammatory response (i.e., interleukins, other cytokines, and prostanoids), and inhibit phagocytosis. Glucocorticoids also induce eosinopenia and lymphopenia. The latter may be attributable to a modification in cell production, distribution, or lysis and is more profound on T lymphocytes than on B lymphocytes. This explains the beneficial effect of glucocorticoids for treatment of certain leukemias, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia of childhood.

Prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone have considerable antiinflammatory activity, intermediate plasma half-lives (allowing easy withdrawal), and relatively low mineralocorticoid activity. These characteristics are ideal for long-term antiinflammatory and immunosuppressant regimens, and prednisone and its derivatives are the most commonly used glucocorticoids for treatment of several autoimmune diseases including collagen diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus and polymyositis-dermatomyositis), vasculitis syndromes (polyarteritis nodosa, giant cell arteritis, and Wegener’s granulomatosis), GI inflammatory diseases (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), and renal autoimmune diseases (glomerulonephritis and the nephrotic syndromes). Intermediate-acting glucocorticoids are also used for treatment of bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (see Chapter 16).

Pharmacovigilance: Clinical Problems, Side Effects, and Toxicity

Exposure to Excessive Levels of Glucocorticoids

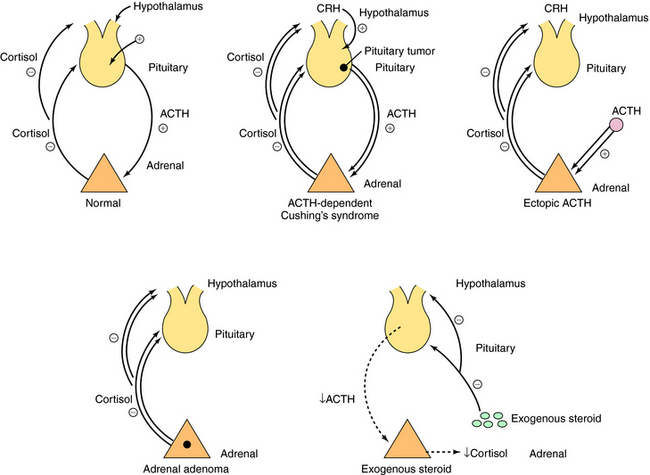

Cushing’s syndrome is associated with excessive exposure to glucocorticoids. Its clinical manifestations include hypertension, truncal obesity, diabetes, hirsutism, acne, ecchymoses, proximal muscle weakness, wide purple stria over the skin, and behavioral abnormalities. The syndrome results most commonly from exogenous administration of glucocorticoids. However, there are also endogenous causes including pituitary ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, ectopic ACTH syndrome, ectopic corticotropin-releasing hormone syndrome, cortisol-secreting adrenal adenomas, and rarely, adrenal carcinoma (Fig. 39-4). To diagnose Cushing’s syndrome, the presence of increased cortisol production must be confirmed by (1) an increased urinary free cortisol concentration and (2) failure of serum cortisol concentrations to be suppressed to less than 5 µg/dL in response to a low dose of dexamethasone. A patient with an increased cortisol production not suppressed by a low dose of dexamethasone should undergo further testing to distinguish among the different causes of Cushing’s syndrome. In most cases a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test can be used to differentiate between pituitary ACTH-dependent Cushing’s disease and other causes of Cushing’s syndrome. For this test serum cortisol concentrations are determined before and after administration of oral dexamethasone for 3 days. If plasma cortisol concentrations decrease to less than 50% of baseline, a pituitary site is indicated; if not, an adrenal tumor or ectopic ACTH syndrome is indicated.

A primary adrenal excess of mineralocorticoids occurs occasionally in patients with adrenal tumors, producing a syndrome of hypertension, hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis, and mild hypernatremia. Both plasma and urinary aldosterone concentrations are elevated in the patient after high Na+ intake. In the absence of a surgical cure, an important inhibitor is spironolactone, which is also used clinically as a diuretic and an antihypertensive agent (Chapter 21). Spironolactone binds to the MR and acts as a competitive antagonist to aldosterone.

Disorders Associated with Decreased Cortisol Production

Decreased cortisol production is associated with either primary or secondary adrenal insufficiency. Primary adrenal insufficiency is most commonly caused by an autoimmune polyendocrine deficiency syndrome. Other causes are tuberculosis, adrenal hemorrhage, granulomatous diseases, amyloidosis, metastatic neoplasia, and congenital unresponsiveness to corticotropin. The secondary causes of adrenal insufficiency include adrenal suppression occurring after the administration of glucocorticoids (very common) or after treatment of Cushing’s syndrome and diseases of the hypothalamus or pituitary gland leading to ACTH deficiency.

Glucocorticoids also affect bone directly by inhibiting osteoblastic activity. Furthermore glucocorticoids may stimulate osteolysis by accelerating transformation of precursor cells to osteoclasts, resulting in increased bone resorption. This is documented by increased concentrations of hydroxyproline in urine as an index of increased bone collagen catabolism. Finally, glucocorticoids block the bone-sparing effect of calcitonin, a peptide synthesized by the parafollicular cells of the thyroid gland that inhibits osteoclastic bone resorption (see Chapter 44).

gastric acid output and inhibiting synthesis of mucopolysaccharides that protect the gastric mucosa from acid. Because even short-term treatment (<1 month) with glucocorticoids may cause gastric irritation or ulcers, some physicians prescribe antacids, proton pump inhibitors or H2-histamine receptor blockers with glucocorticoids (see Chapter 18).

Anonymous. Fluticasone furoate (Veramyst) for allergic rhinitis. Med Lett. 2007;49:90-92.

Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson AB, et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: A consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5593-5602.

Rhen T, Cidlowski JA. Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids—new mechanisms for old drugs. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1711-1723.

Speiser P, White PC. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:76-788.

Walsh JP, Dayan CM. Role of biochemical assessment in management of corticosteroid withdrawal. Ann Clin Biochem. 2000;37:279-288.