Adolescent medicine

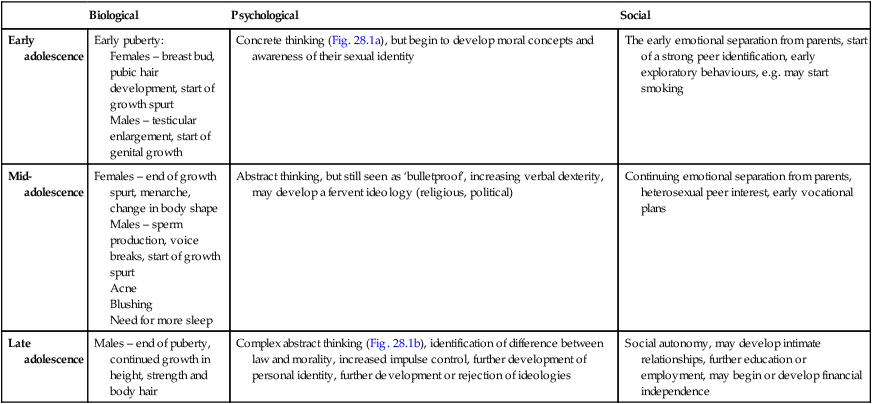

The transition from being a child to an adult involves many biological, psychological and social changes (Table 28.1). Pubertal development is considered in Chapter 11. Difficulties may arise if the pubertal changes are early or delayed.

Table 28.1

Developmental changes of adolescence

| Biological | Psychological | Social | |

| Early adolescence | Early puberty: Females – breast bud, pubic hair development, start of growth spurt Males – testicular enlargement, start of genital growth |

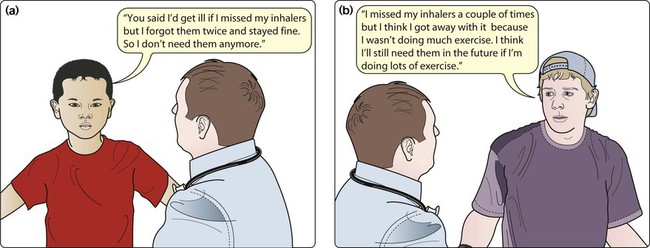

Concrete thinking (Fig. 28.1a), but begin to develop moral concepts and awareness of their sexual identity | The early emotional separation from parents, start of a strong peer identification, early exploratory behaviours, e.g. may start smoking |

| Mid-adolescence | Females – end of growth spurt, menarche, change in body shape Males – sperm production, voice breaks, start of growth spurt Acne Blushing Need for more sleep |

Abstract thinking, but still seen as ‘bulletproof’, increasing verbal dexterity, may develop a fervent ideology (religious, political) | Continuing emotional separation from parents, heterosexual peer interest, early vocational plans |

| Late adolescence | Males – end of puberty, continued growth in height, strength and body hair | Complex abstract thinking (Fig. 28.1b), identification of difference between law and morality, increased impulse control, further development of personal identity, further development or rejection of ideologies | Social autonomy, may develop intimate relationships, further education or employment, may begin or develop financial independence |

Adapted from Adolescent development. In: Viner R, ed. 2005. ABC of Adolescence. Blackwell, Oxford.

Communicating with adolescents

Some practical points about communicating and working with adolescents are:

• Make the adolescent the central person in the consultation.

• Be yourself. When establishing rapport, it may be appropriate to engage the adolescent by talking about their interests, e.g. football, clothes or music, but do not try to be cool, false or patronising; your relationship should be as their doctor, not their friend.

• Consider the family dynamics. Is the mother or father answering for the adolescent? Does the adolescent seem to want this or resent being interrupted?

• Avoid being judgemental or lecturing. Avoid ‘You ….’ statements and use ‘I ….’ statements in preference, e.g. ‘I am concerned that you ….’. A frank and direct approach works best. Your role should be that of a knowledgeable, trusted adult from whom they can get advice if they so choose.

• An authoritarian approach is likely to result in a rebellious stance. Working things out together in a practical way has the best chance of success.

• Frame difficult questions so they are less threatening and judgemental, e.g. ‘Lots of teenagers drink alcohol, do any of your friends drink? How much do they drink in a week? Do you drink alcohol – how much do you drink compared to them?’ Likewise, when asking sensitive questions on, e.g. sexual health, always give young people warning and explain the rationale of why such questions need to be asked.

• Confidentiality is particularly important to this age group and must be respected. Explain that you will keep everything you are told confidential, unless they or somebody else is at risk of serious harm. Always assess their understanding of confidentiality and correct any misunderstanding.

• Bear in mind proxy presentations, e.g. abdominal pain, when the real reason is anxiety about the possibility of pregnancy, or sexually transmitted infection or the result of recreational drug use.

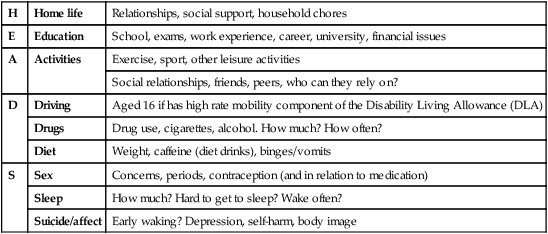

• A full adolescent psychosocial history is useful to engage the young person, to assess the level of risk as well as provide information which will aid the formulation of effective interventions. The HEADS acronym may be helpful in this regard (Table 28.2), although questions must always be tailored to stage of development and the right of the young person to not answer should be respected.

Table 28.2

HEADS acronym for psychosocial history taking in adolescents

| H | Home life | Relationships, social support, household chores |

| E | Education | School, exams, work experience, career, university, financial issues |

| A | Activities | Exercise, sport, other leisure activities |

| Social relationships, friends, peers, who can they rely on? | ||

| D | Driving | Aged 16 if has high rate mobility component of the Disability Living Allowance (DLA) |

| Drugs | Drug use, cigarettes, alcohol. How much? How often? | |

| Diet | Weight, caffeine (diet drinks), binges/vomits | |

| S | Sex | Concerns, periods, contraception (and in relation to medication) |

| Sleep | How much? Hard to get to sleep? Wake often? | |

| Suicide/affect | Early waking? Depression, self-harm, body image |

• Communicate and explain concepts appropriate to their cognitive development. For young adolescents, use concrete examples (‘here and now’) rather than abstract concepts (‘if … then’) .

• History-taking should avoid making the assumption of heterosexuality with questions about romantic and sexual partners asked in a gender neutral way.

• If they need to have a physical examination, consider their privacy and personal integrity – Who do they want present? As with any age, young people have the right to a chaperone but it should not be assumed the young person will want this to be their parent. Also, find out if they would prefer a doctor of the same sex, if this is an option.

Consent and confidentiality

Consent

In the UK, young people can give consent if they are sufficiently informed and either over 16 years old or under 16 years and competent to make decisions for themselves. Conflict rarely arises about a treatment, as usually the adolescent, their parents and doctors agree that it is necessary. Handling of disagreement over consent is considered in Chapter 5.

Range of health problems

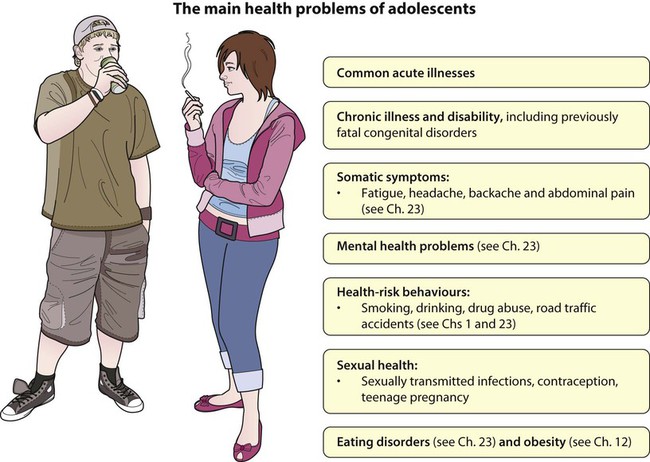

• Common acute illnesses: respiratory disorders, skin conditions, musculoskeletal problems including sports injuries and somatic complaints. Acute serious illness has become rare, with mortality predominantly from trauma

• Chronic illness and disability: e.g. asthma, epilepsy, diabetes, cerebral palsy, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, sickle cell disease. The prevalence of some of the common chronic disorders in adolescence is shown in Table 28.3. There is also a range of uncommon disorders with serious chronic morbidity such as malignant disease and connective tissue disorders. In addition, children with many congenital disorders which often used to be fatal in childhood now survive into adolescence or adult life, e.g. cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, complex congenital heart disease, metabolic disorders, etc.

Table 28.3

Prevalence of some chronic illnesses per 1000 adolescents (12–18 years old)

| Disease | Prevalence per 1000 adolescents |

| Musculoskeletal conditions | 41 |

| Skin conditions | 32 |

| Significant mental health problems | 120 |

| Diabetes | |

| Type 1 | 2 |

| Type 2 | 1–2 |

| Respiratory conditions | 150 |

| Asthma | 100 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 0.1 |

| Epilepsy | 4 |

| Hearing problems | 18 |

| Cerebral palsy | 1.5 |

• High prevalence of somatic symptoms: fatigue, headaches, backache, etc.

• Mental health problems including suicide and deliberate self-harm

• Eating disorders and weight problems

• Those associated with health-risk behaviours, such as smoking, drinking, drug abuse and sexual health, contraception and teenage pregnancy.

Mortality

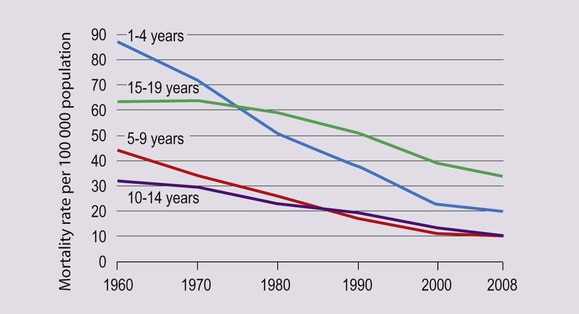

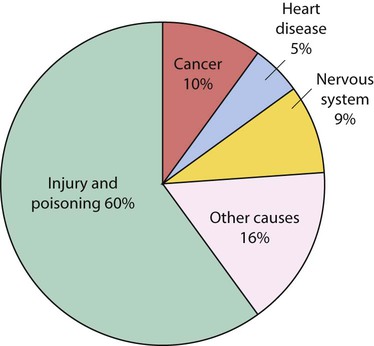

The dramatic improvement in the mortality of young children seen since the 1960s has not been matched in adolescents, who now have a higher mortality rate than that of 1–4-year-olds (Fig. 28.2). Although deaths in adolescents from communicable diseases have declined markedly, this has not been matched by mortality from road traffic accidents, other injuries and suicide, and these now predominate (Fig. 28.3). Alcohol is thought to be a contributing factor in one-third of these deaths.

Impact of chronic conditions

Chronic illness may disrupt biological, psychological and social development. In addition, these developmental changes may affect the control and management of the disorder (Table 28.4). The impact of chronic illness on children, young people and their families is considered in Chapter 23.

Table 28.4

Some of the ways in which chronic illness and development interact with each other

| Effect of chronic illness on development | Effect of development on chronic illness | |

| Biological | Delayed puberty Short stature Reduced bone mass accretion Malnutrition secondary to inadequate intake due to increased caloric requirement of disease or anorexia Localised growth abnormalities in inflammatory joint disease, e.g. premature fusion of epiphyses |

Pubertal hormones may impact on disease, e.g. growth hormone worsens diabetes and increases insulin requirements; females with cystic fibrosis may have deterioration in lung function; corticosteroid toxicity worse in peripubertal phase Increased caloric requirement may worsen disease control or result in undernutrition – may need dietary supplements or overnight feeding with nasogastric tube or gastrostomy Growth may cause scoliosis |

| Psychological | Regression to less mature behaviour Adopt sick role Impaired development of sense of attractive/sexual self Parental stress, depression, financial problems in providing care; siblings may suffer |

Deny that their health may suffer from their actions Poor adherence and disease control Reject medics like parents |

| Social | Reduced independence when should be separating Failure of peer relationships Social isolation – unable to participate in sports or social events School absence and decline in school performance, may lower self-esteem Vocational failure |

Risk behaviour may adversely affect disease, e.g. smoking and asthma or cystic fibrosis, alcohol and diabetic control, sleep deprivation and epilepsy Chaotic eating habits lead to malnutrition or obesity |

Adherence

Adherence may be influenced by lack of knowledge and/or poor recall of previous disease education. The disorder may have presented when the child was much younger, so that the original consultation will have taken place primarily between the doctor and parents. If this communication has not been updated with increasing age, the adolescent’s knowledge may be poor, with little understanding about his/her illness, what medications he/she is taking and why. As the responsibility for management moves to the young person, information needs to be provided about medications and treatment appropriate for his/her development. Other ways to maximise adherence are summarised in Table 28.5.

Table 28.5

| Assess the size of the problem and be non-judgemental | Ask: ‘Most people have trouble taking their medication. When was the last time you forgot?’ |

| Take time to explore practicalities | Try to put yourself in the adolescent’s shoes and think through the detail of their regimen with them. Make regimen as simple as possible. Don’t forget practical issues – poor adherence may be as simple as not having anywhere private at school to take the treatment |

| Explore beliefs | May harbour strange or incorrect beliefs about medications, e.g. falsely attribute a side-effect and therefore refuse to take the medication |

| Use daily routines to ‘anchor’ adherence | Find daily activities to anchor taking the medication, e.g. brushing teeth, or ‘with breakfast and dinner’ instead of ‘twice a day’. Find the least chaotic time of day: may be morning or evening! Let the suggestions come from the adolescent |

| Motivation | Negotiate short-term treatment goals. Search for factors that motivate the young person |

| Involve and contract | Plan the regimen with the adolescent. Some may respond to a written contract that both sides agree to stick to |

| Written instructions | Most of what is said has been shown to be forgotten once they leave the room! |

| Take time to explain | Check level of knowledge on each occasion |

| Solution-focused approach | Find out what has been going well and why. Use this information, e.g. ‘How have you managed to remain out of hospital for 3 weeks this month?’ |

Fatigue, headache and other somatic symptoms

Occasionally, the symptoms are so severe and persistent that they considerably affect quality of life, with impairment of school attendance, academic results and peer relationships. This may be from chronic fatigue syndrome or chronic idiopathic pain syndromes. Further investigation and assessment will be required and multidisciplinary rehabilitation and cognitive behavioural therapy within the family may be beneficial. The management of somatic symptoms and chronic fatigue syndrome are considered further in Chapter 23.

Mental health problems

The prevalence of mental health problems in adolescents is estimated to be about 11%. The main problems are listed in Table 28.6.

Table 28.6

Main mental health problems and disorders in adolescents

| Problem or disorder | Prevalence (%) |

| Depression | 3–5 |

| Anxiety | 4–6 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 2–4 |

| Eating disorders | 1–2 |

| Conduct disorder | 4–6 |

| Substance misuse disorder | 2–3 |

Source: Michaud P-A, Fombonne E. 2005. Common mental health problems. In: Viner R, ed. 2005. ABC of Adolescence. Blackwell, Oxford.

Eating disorders are common during adolescence. About 40% of females and 25% of males begin dieting in adolescence because of dissatisfaction with their body. In anorexia nervosa and bulimia, there is a morbid preoccupation with weight and body shape. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 23.

Health promotion

The reasons to undertake health promotion in adolescents are:

• It is the period for starting health-risk behaviours (smoking, alcohol, drug misuse, unsafe sexual activity)

• Health-risk behaviours started in adolescence often continue into adult life

• Health behaviours may have a direct effect on their lives, e.g. teenage pregnancy, road traffic accidents

The main areas for health promotion are:

There are a number of approaches to health promotion for adolescents:

• Provide suitable information in a user-friendly way for young people. An example is the website: Teenage Health Freak (Fig. 28.4).

• Health promotion by society as a whole, e.g. banning cigarette advertising, making emergency contraception available in pharmacies. These can be very effective. However, there is increasing evidence that improving the socioeconomic circumstances of young people would be the most effective intervention for health promotion. Also, as adolescents often embark on more than one risk behaviour, tackling the underlying problem may reduce other risk-taking behaviours: e.g. a programme to reduce bullying in a whole school may also reduce other behaviour such as drug misuse.

• Training programmes to improve adolescents’ ability to accept or reject certain courses of behaviour can be effective for the individual, but is time-consuming and expensive.

• Health promotion by professionals. Exhorting adolescents not to smoke, to eat a balanced diet, use contraception, etc., has not been found to be effective, and may be counter-productive. Health professionals do have a role in health promotion at an individual level. It is likely to be most effective if targeted at those who are receptive or contemplating change in their health-risk behaviour. However, motivational interviewing techniques (which do not assume that they are ready to change their behaviour, but aim to increase their intrinsic motivation to change) have also been shown to be useful with this age group.