Chapter 35 Additional Agents and Miscellaneous Therapies

Sedative-Hypnotics

These drugs in general, and clonazepam in particular, were among the first used and reported on (in 1979) for the treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS).1 However, their ability to specifically alleviate RLS symptoms is controversial. At one time, they were commonly recommended for the treatment of RLS, but most RLS experts use these drugs primarily as supplementary therapy to treat the insomnia associated with RLS,2 although some patients may respond to monotherapy. The early reports of success in RLS with benzodiazepines did not use validated instruments and may have depended largely on the alleviation of sleep-related or bedtime complaints. In the modern era with more sophisticated controlled designs and validated assessments, there have been no studies with benzodiazepines and few with newer sedative-hypnotics. The majority of studies are open label and may have been contaminated by the placebo effect, which is common to RLS treatment trials using subjective measures.3 This placebo effect may account for much of the relief of any daytime symptoms attributed to the benzodiazepines. Even in the placebo-controlled trials, the marked improvement of disruptive sleep patterns due to the use of these drugs and resultant increased daytime well-being may decrease the perception of bothersome daytime RLS symptoms.

Another concern about the use of sedative-hypnotics (especially with their daytime use or with the bedtime use of long-acting ones that may carry over into the next day) is that they have a potential for worsening daytime RLS symptoms4 if they induce sedation. One study found that intravenous administration of diphenhydramine 25 mg or lorazepam 0.5 mg to 12 RLS patients who were adequately treated with dopamine agonists caused both similar and severe exacerbations of their otherwise controlled RLS symptoms.4 Further, they can increase the risk of accidents, including falls in the elderly and errors during activities that require vigilance, such as driving.

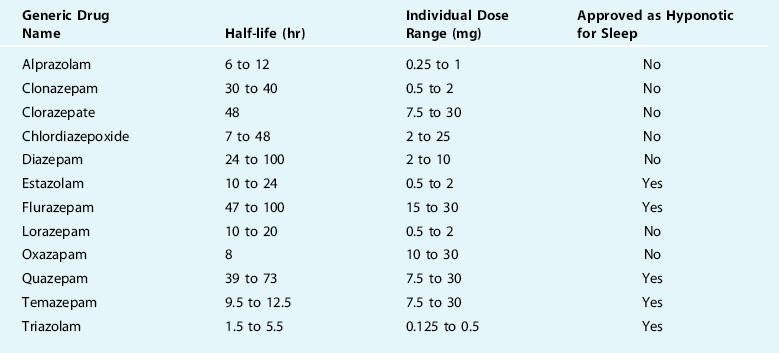

However, when choosing a sedative-hypnotic, it is generally best to select one that has a quick onset to promote sleep initiation and a relatively short half-life to prevent daytime sleepiness or drowsiness that in turn may promote increased daytime RLS symptoms (Tables 35-1 and 35-2). For chronic daily use, the nonbenzodiazepines (Table 35-2) are greatly preferred due to their decreased side effect profile and markedly decreased risks of tolerance and dependence. Much of the selection depends on clinical judgment, because there is little specific evidence to support use of the agents in RLS.

| Generic Drug Name | Half-life (hr) | Individual Dose Range (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Ramelteon | 1 to 2.6 | 8 |

| Eszopiclone | 6 | 1 to 3 |

| Zaleplon | 1 | 10 to 20 |

| Zolpidem | 2.5 | 5 to 10 |

| Zolpidem slow release | 2.8 | 6.25 to 12.5 |

The European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) task force recommendation for the use of sedative-hypnotics is that clonazepam should be considered as probably effective for improving symptoms in primary RLS when given at 1 mg before bedtime but also probably as ineffective when given at four doses throughout the day. However, any of the benzodiazepines that are approved for sleep (see Table 35-1) and all of the nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (see Table 35-2) can be used for their approved indication to aid sleep, which is often necessary for the RLS population.

Benzodiazepines

This group comprises several drugs that share similarities and are marketed either as a hypnotic for inducing sleep or to treat anxiety (see Table 35-1). Despite being approved and marketed only as a sedative, some of these drugs may be suitable for use as a hypnotic. The discussion below will review the literature on the use of these medications for treating RLS.

Clonazepam

Clonazepam was used, beginning in 1979, to treat RLS. It was probably introduced into RLS because of the association with PLMS, then usually termed nocturnal myoclonus: at that time, clonazepam was one of the mainstays of general myoclonus treatment. The first reports were just small cases series.1,5 The first double-blind crossover trial of clonazepam was a comparative trial against vibration in six subjects.6 Clonazepam, but not vibration, was more effective than placebo and was also well tolerated with significant adverse effects.6 However, the next study, also a placebo-controlled double blind crossover study, did not find clonazepam to be more effective than placebo.7 As a result of these mixed results, the EFNS recommendation for clonazepam was that it is probably effective for RLS when given at 1 mg before bedtime but was probably ineffective when given at 4 doses throughout the day.8

The concern with this drug is that it has a 30- to 40-hour half-life, which may easily result in next-day sedation, especially when taken for several nights consecutively. Some studies have suggested that this adverse effect may not be clinically significant for many patients, including the elderly.9 This daytime sedation is often not apparent to the patient, especially compared with their previous RLS-induced, sleep-deprived state. As other shorter-acting sedative-hypnotics have been shown to be effective for RLS (see later), there are alternatives that may be safer and also inexpensive. Tolerance and dependence are real risks with benzodiazepines, although this may not be a universal finding.9

Alprazolam

An open-label study examined alprazolam at 0.5 mg to 1 mg at bedtime given to 10 subjects with RLS.10 Eight of 10 patients were said to improve on alprazolam. One patient stated that taking 0.5 mg of the drug before going to the theater would provide her with relief throughout the entire evening. Alprazolam, although not approved as a hypnotic, can still be a reasonable choice for that purpose. Its onset is rapid and has a short to medium-duration half-life of 6 to 12 hours that at lower doses may avoid daytime sedation. Similar to other benzodiazepines, tolerance and dependence may occur with chronic daily use.

Triazolam

There is one report of triazolam 0.25 mg taken at bedtime helping one patient with RLS for 6 months.11 This patient stopped the drug and experienced recurrence of her symptoms within 48 hours. There are also several articles demonstrating the benefits of triazolam12–14 for PLM. These studies demonstrated improvements in sleep architecture by increasing total sleep time, decreasing the number of awakenings and arousals, decreasing stage 1 sleep, while increasing stage 2 sleep and increasing sleep efficiency. Additionally, daytime sleepiness was diminished. Although the number of PLM was not decreased, there was a major decline in the number of arousals and awakenings from the PLM. Triazolam has a very quick onset of action and a very short half-life of 1.5 to 5.5 hours that limits next-day drowsiness. However, use of this drug has been associated with a significant degree of retrograde amnesia and rebound insomnia, which limit enthusiasm for its use.

Temazepam

No studies have yet evaluated this drug for RLS. However, one study has shown the efficacy of temazepam for PLS.15 Improvements in sleep similar to those noted above for triazolam were also observed with temazepam. This drug has an onset after 45 to 60 minutes with a half-life of about 9 to 12 hours. No studies have yet been done in RLS.

Nonbenzodiazepines

Zolpidem

This drug was studied for RLS in one open-label prospective trial on eight subjects who were unresponsive or could not tolerate L-dopa and benzodiazepines.16 All patients were reported to have complete relief of their RLS symptoms within an average of 4 days of starting zolpidem at 10 mg that lasted 12 to 30 months with no relapses or side effects. Two patients stopped their medication after 1 year of treatment and had their symptoms return, then go away again with re-institution of zolpidem. Zolpidem has a very quick onset of action and a short half-life of 2.5 hours, which ensures that most patients will not experience daytime sleepiness. It has been associated with abnormal sleep-related behaviors such as sleep walking, talking, or sleep-related eating disorders17 but otherwise has been well tolerated. There is a controlled-release version of this drug that increases the half-life and releases some of the drug immediately, while the rest is released later in the sleep period to help maintain sleep.

Other Sedative-Hypnotic Agents

None of the other nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics has been studied for activity and tolerability in RLS. For those who have problems with sleep maintenance or obtaining sufficient sleep time, eszopiclone with its longer half-life of 6 hours may be more appropriate than zolpidem. On the other hand, those who feel the residual sedation in the morning may benefit from the shorter half-life (1 hour) of zaleplon. Due to its very short half-life, patients can take zaleplon for their middle of the night awakenings and not wake up sleepy a few hours later. Ramelteon is very different from all the other hypnotic drugs discussed earlier. It does not act on the GABA receptors that help promote sleep but rather on the melatonin receptors. This drug, which has relatively few side effects, is indicated for sleep-onset insomnia, because its effects on improving sleep maintenance are much less pronounced.18 It has not yet been determined how well this drug works in comparison with the more traditional hypnotic drugs for both insomnia and RLS.

Other Oral Medications

Clonidine

This drug, which stimulates α-adrenoceptors in the brainstem, is approved in the United States for treating hypertension and was first used for RLS in 1985.19 Several other reports have described the use of clonidine for treating primary RLS20–22 with one 2-week double-blind trial.23 This double-blind study started their subjects on 0.1 mg of clonidine twice daily (2 hours before symptoms generally occur and again at bedtime) and then titrated by 0.1 mg every 1 to 2 days until symptoms were relieved or a maximum of 1 mg/day. Clonidine was found to be effective in relieving the leg sensations and morning drowsiness. Sleep latency was decreased (likely due to the sedative effects of the drug); however, sleep time, sleep efficiency, the number of PLMS, and arousals or awakenings were not improved. Side effects include dry mouth, decreased cognition and libido, lightheadedness, sleepiness, and headache.

Due to the lack of general experience with this drug, it might be dosed according to the double-blind study.23 Clonidine may be a reasonable therapy for people with RLS who also have hypertension. In addition, for those who are intolerant of this drug by the oral route, some may benefit from the newer transdermal patch, which avoids the gastrointestinal system and may produce more steady serum drug levels. The EFNS has indicated that clonidine is probably effective (class B) at reducing symptoms and sleep latency in primary RLS in the short term.8

Amantadine

Amantadine is approved in the United States for use in Parkinson’s disease, for the prophylaxis of influenza A, and for drug-induced extrapyramidal reactions. The exact mechanism of action of this drug for Parkinson’s disease or RLS is unknown but may involve increasing the synthesis or release of dopamine or decreasing presynaptic reuptake of dopamine. After oral administration, amantadine reaches peak plasma concentration in about 3 hours, has a half-life of about 17 hours, and is excreted unchanged though the kidneys. Only one study has examined the use of amantadine for treating RLS.24 This open-label trial treated 21 patients with amantadine, often as an add-on medication, starting at 100 mg/day, increasing to a maximum of 300 mg/day until symptoms were relieved or intolerable side effects were experienced. Eleven of the patients responded to the drug at a mean dose of 227 mg/day with 6 complete responders. The most common side effects were drowsiness, fatigue, and insomnia (similar to dopaminergic medications) and only 2 subjects stopped the drug due to these side effects. This drug may provide dopaminergic enhancement for subjects who cannot tolerate agonists or levodopa.

Other Oral Agents Mentioned in the Literature

β-Blockers: Propranolol

In 1967, one investigator reviewed 40 cases of RLS found in 600 of his Parkinson’s disease patients. Based on his experience, he commented that 5 to 10 mg of the β-blocker propranolol taken at dinner and if needed before bedtime worked well for RLS both therapeutically and prophylactically.25 Two other cases reports also reported efficacy in RLS.26,27 Other experience is lacking, but β-blockers have also been used for treatment of akathisia, which can resemble RLS.28

Vitamins

Vitamin B12 and folate were reported to benefit RLS in a few uncontrolled open case series.29–31 Fifteen patients with RLS and other neurological disorders in an open-label trial responded to folic acid at doses of 1.25 to 30 mg/day.31 Because folic acid deficiency has been noted in pregnant women with RLS,32 it may be important to be sure such patients receive folic acid supplements.

Two reports of case series found that vitamin E could benefit RLS.33,34 However, there are no recent studies to support this vitamin’s use.

Other Routes for Treatment, Surgical, and Additional Approaches to Restless Legs Syndrome

Transdermal Treatment

As discussed in Chapter 31, two agonists have been formulated in patches—rotigotine, a nonergot agonist,36 and lisuride, an ergot derivative—that may not have same risk of fibrotic complications as other ergot-derived agonists.37 Clonidine is also available in a transdermal formulation38 as are some opioids, such as fentanyl.39 The advantages of this formulation is that it both avoids the oral route and generally delivers a fairly constant drug over a period of a day or more. The major disadvantage—cutaneous skin reactions40—is a relatively unique adverse event. Although it can be fairly common in RLS treatment, it is not usually a reason for discontinuing treatment in therapeutic trials.36 Other dopaminergic side effects tend to be comparable with those of oral agonists with transdermal agonist treatment.36

Subcutaneous Injection

The mixed dopamine and opioid agonist apomorphine has been reported beneficial in pilot studies of RLS.41–43 The advantages of this system include its usefulness when oral input is not possible and its rapid onset of action; its disadvantage is its brief duration of action, requiring frequent repeated injections. An oral formulation may be developed.

Intramuscular Injection

Iron is available for intramuscular injection but has not been used for RLS. Various opioids can also be injected. Botulinum toxin type A, which is derived from the exotoxin produced by Clostridium botulinum type A, is approved in the United States for use in the treatment of cervical dystonia in adults, severe primary axillary hyperhidrosis, strabismus, and blepharospasm associated with dystonia and for cosmetic treatment of wrinkles. In one study performed on this drug for RLS, it was given intramuscularly to three patients who were ineligible for oral therapy.44 Injections were given at the sites of their RLS symptoms and improvement was noted within a few days. The duration of this effect appeared to be about 12 weeks when patients would get reinjected and continue to respond to this therapy. No adverse effects were noted with treatment. This unique treatment of RLS clearly needs further investigation before being recommended. In fact, there are some anecdotal cases of exacerbating RLS with this treatment.

Epidural and Intrathecal Delivery

There is one report of an emergent treatment of severe, intractable RLS “status” with epidural delivery of morphine45 and two cases treated with intrathecal morphine and bupivacaine.46 These routes may offer additional complications, such as meningitis, local infection, or hemorrhage, but have the advantages in delivering much smaller doses that can be better tolerated because they are more exactly targeted. Implanted pumps can deliver regular doses. They may be explored in the future for severe cases, particularly those which have developed intractable augmentation on dopaminergics.

Nerve, Spinal Cord, and Deep Brain Stimulation

One case report found that RLS resolved after vagal nerve stimulation,47 an approved treatment for epilepsy,48 but also for pain,49 which may be more relevant to RLS. Anecdotal reports have suggested that spinal cord stimulation may benefit RLS, but there are no published reports on this. After an initial report of improvement of RLS with an ablative pallidotomy,50 there have been a number of reports of changes in RLS with deep brain stimulation. These have not been consistent. RLS was improved by pallidal stimulation51 and subthalamic nucleus (STN) stimulation52 in reports of patients with comorbid movement disorders and RLS. In one study, Parkinson’s disease patients after STN stimulator implantation had an emergence of RLS symptoms,53 but this may have been due to reduced dopaminergic medication. RLS has been associated with essential tremor,54 but thalamic stimulation (VIM) for essential tremor has been reported not to benefit comorbid RLS symptoms.55

Other Surgical Approaches

There was one initial report on sclerotherapy as benefiting almost all treated RLS patients with varicose veins,56 although repeated treatments were sometimes required and benefit was transient for some. However, that report did not provide clear diagnostic criteria for RLS and a later study suggested that RLS symptoms may not be common in varicose veins,57 raising questions whether the varicose vein subjects in the sclerotherapy trial did have RLS.

1. Matthews WB. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with clonazepam. Br Med J. 1979;1:751.

2. Silber MH, Ehrenberg BL, Allen RP, et al. An algorithm for the management of restless legs syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:916-922.

3. Fulda S, Wetter TC. Where dopamine meets opioids: A meta-analysis of the placebo effect in RLS treatment studies. Brain. 2008;131:902-917.

4. Allen RP, Lesage S, Earley CJ. Anti-histamines and benzodiazepines exacerbate daytime restless legs syndrome symptoms [abstract]. Sleep. 2005;28:A279.

5. Boghen D. Successful treatment of restless legs with clonazepam. Ann Neurol. 1981;8:341.

6. Montagna P, de Bianchi LS, Zucconi M, et al. Clonazepam and vibration in restless leg syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand. 1984;69:428-430.

7. Boghen D, Lamothe L, Elie R, et al. The treatment of the restless legs syndrome with clonazepam: A prospective controlled study. Can J Neurol Sci. 1986;13:245-247.

8. Vignatelli L, Billiard M, Clarenbach P, et al. EFNS guidelines on management of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in sleep. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:1049-1065.

9. Schenck CH, Halfaker BA, Mahowald MW. Sustained benefit and low risk of major adverse effects during long-term nightly benzodiazepine and/or opiate treatment of injurious parasomnias, restless legs/periodic limb movement disorder and insomnia in 121 adult patients. Sleep Res. 1994;24:81.

10. Scharf MB, Brown L, Hirschowitz J. Possible efficacy of alprazolam in restless leg syndrome. Hillside J Clin Psychiatry. 1986;8:214-223.

11. Tollefson G, Erdman C. Triazolam in the restless legs syndrome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1985;5:361-362.

12. Doghramji K, Browman CP, Gaddy JR, Walsh JK. Triazolam diminishes daytime sleepiness and sleep fragmentation in patients with periodic leg movements. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1991;11:284-290.

13. Bonnet MH, Arand DL. The use of triazolam in older patients with periodic leg movements, fragmented sleep, and daytime sleepiness. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M139-144.

14. Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Chronic use of triazolam in patients with periodic leg movements, fragmented sleep and daytime sleepiness. Aging (Milano). 1991;3:313-324.

15. Mitler MM, Browman CP, Menh SJ, et al. Nocturnal myoclonus: Treatment efficacy of clonazepam and temazepam. Sleep. 1986;9:385-392.

16. Bezerra ML, Martinez JV. Zolpidem in restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2002;48:180-181.

17. Morgenthaler TI, Silber MH. Amnestic sleep-related eating disorder associated with zolpidem. Sleep Med. 2002;3:323-327.

18. Borja NL, Daniel KL. Ramelteon for the treatment of insomnia. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1540-1555.

19. Handwerker JV, Palmer RF. Clonidine in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1228-1229.

20. Bastani B, Westervelt FB. Effectiveness of clonidine in alleviating the symptoms of “restless legs” [letter]. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10:326.

21. Cavatorta F, Vagge R, Solari P, et al. Risultati preliminari con clonidina nella sindrome delle gambe senza riposo in due pazienti uremici emodializzati. Min Urol Nefrol. 1987;39:93.

22. Zoe A, Wagner ML, Walters AS. High-dose clonidine in a case of restless legs syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 1994;28:878-881.

23. Wagner ML, Walters AS, Coleman RG, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of clonidine in restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:52-58.

24. Evidente VG, Adler CH, Caviness JN, et al. Amantadine is beneficial in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2000;15:324-327.

25. Strang RR. The symptom of restless legs. Med J Aust. 1967;1:1211-1213.

26. Ginsberg HN. Propranolol in the treatment of restless legs syndrome induced by imipramine withdrawal. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:938.

27. O’Sullivan RL, Greenberg DB. H2 antagonists, restless leg syndrome, and movement disorders. Psychosomatics. 1993;34:530-532.

28. Sachdev P. Akathisia and Restless Legs. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

29. Botez MI. Folate deficiency and neurological disorders in adults. Med Hypotheses. 1976;2:135-140.

30. Botez MI, Fontaine F, Botez T, et al. Folate-responsive neurological and mental disorders: Report of 16 cases. Eur Neurol. 1977;15:230-246.

31. Botez MI, Lambert B. Folate deficiency and restless-legs syndrome in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:670.

32. Lee KA, Zaffke ME, Baratte-Beebe K. Restless legs syndrome and sleep disturbance during pregnancy: The role of folate and iron. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:335-341.

33. Ayres SJr, Mihan R. Leg cramps (systremma) and “restless legs” syndrome. Response to vitamin E (tocopherol). Calif Med. 1969;111:87-91.

34. Ayres S, Mihan R. Nocturnal leg cramps (systremma): A progress report on response to vitamin E. South Med J. 1974;67:1308-1312.

35. Hornyak M, Voderholzer U, Hohagen F, et al. Magnesium therapy for periodic leg movements-related insomnia and restless legs syndrome: An open pilot study. Sleep. 1998;21:501-505.

36. Oertel WH, Benes H, Garcia-Borreguero D, et al. Efficacy of rotigotine transdermal system in severe restless legs syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, six-week dose-finding trial in Europe. Sleep Med. 2008;9:228-239.

37. Benes H. Transdermal lisuride: short-term efficacy and tolerability study in patients with severe restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2006;7:31-35.

38. Prisant LM, Bottini B, DiPiro JT, Carr AA. Novel drug-delivery systems for hypertension. Am J Med. 1992;93:45S-55S.

39. Skaer TL. Transdermal opioids for cancer pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:24.

40. Musel AL, Warshaw EM. Cutaneous reactions to transdermal therapeutic systems. Dermatitis. 2006;17:109-122.

41. Haba-Rubio J, Staner L, Cornette F, et al. Acute low single dose of apomorphine reduces periodic limb movements but has no significant effect on sleep arousals: A preliminary report. Neurophysiol Clin. 2003;33:180-184.

42. Tings T, Stiens G, Paulus W, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with subcutaneous apomorphine in a patient with short bowel syndrome. J Neurol. 2005;252:361-363.

43. Tribl GG, Sycha T, Kotzailias N, et al. Apomorphine in idiopathic restless legs syndrome: An exploratory study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:181-185.

44. Rotenberg JS, Canard K, Difazio M. Successful treatment of recalcitrant restless legs syndrome with botulinum toxin type-A. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:275-278.

45. Vahedi H, Kuchle M, Trenkwalder C, et al. [Peridural morphine administration in restless legs status (published erratum appears in Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 1994;29:521)]. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 1994;29:368-370.

46. Jakobsson B, Ruuth K. Successful treatment of restless legs syndrome with an implanted pump for intrathecal drug delivery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:114-117.

47. Merkl A, Brakemeier EL, Danker-Hopfe H, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation improves restless legs syndrome associated with major depression: A case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:635-636.

48. Groves DA, Brown VJ. Vagal nerve stimulation: A review of its applications and potential mechanisms that mediate its clinical effects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:493-500.

49. Multon S, Schoenen J. Pain control by vagus nerve stimulation: From animal to man … and back. Acta Neurol Belg. 2005;105:62-67.

50. Rye DB, DeLong MR. Amelioration of sensory limb discomfort of restless legs syndrome by pallidotomy [letter]. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:800-801.

51. Okun MS, Fernandez HH, Foote KD. Deep brain stimulation of the GPi treats restless legs syndrome associated with dystonia. Mov Disord. 2005;20:500-501.

52. Driver-Dunckley E, Evidente VG, Adler CH, et al. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease patients may improve with subthalamic stimulation. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1287-1289.

53. Kedia S, Moro E, Tagliati M, et al. Emergence of restless legs syndrome during subthalamic stimulation for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2004;63:2410-2412.

54. Ondo WG, Lai D. Association between restless legs syndrome and essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2006;21:515-518.

55. Ondo W. VIM deep brain stimulation does not improve pre-existing restless legs syndrome in patients with essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2006;12:113-114.

56. Kanter AH. The effect of sclerotherapy on restless legs syndrome. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:328-332.

57. Bradbury A, Evans C, Allan P, et al. What are the symptoms of varicose veins? Edinburgh vein study cross sectional population survey. BMJ. 1999;318:353-356.