Acute viral infections

Classifications of viral infections of the CNS such as those shown in Table 12.1 are of help in making an accurate diagnosis. In practice, a combination of approaches is generally used to classify and diagnose these disorders.

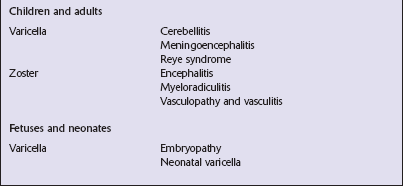

Table 12.1

Viral infections of the central nervous system

These may be classified according to:

Course of disease

Acute

Subacute or chronic

Most severely involved/target tissue

Meningitis

Poliomyelitis, polioencephalomyelitis

Viral leukoencephalopathy

Panencephalitis

Patient age group

Fetal

Neonatal

Child

Adult

Patient immune status

Etiologic agent

ASEPTIC MENINGITIS

This is a benign, usually short-lived, syndrome of meningeal inflammation that is not attributable to any of the common bacterial pathogens. A wide range of viruses can cause aseptic meningitis (Table 12.2); much less common causes include some bacteria (e.g. in syphilis and Lyme disease) and other microorganisms, non-infective inflammatory disorders (e.g. Behçet’s disease), tumors (e.g. epidermoid and dermoid cysts), and drugs (e.g. ibuprofen). One form of recurrent aseptic meningitis (Mollaret’s) that was previously regarded as non-infective has been linked to infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV), especially HSV-2.

Table 12.2

Common viral causes of aseptic meningitis

Echovirus

Coxsackie B

Coxsackie A

Herpes simplex virus (HSV)-2

Mumps

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Lymphochoriomeningitis virus

Arboviruses

Measles

Parainfluenza virus

Adenovirus

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

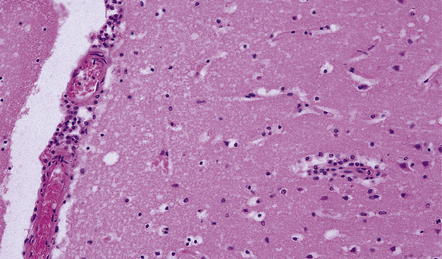

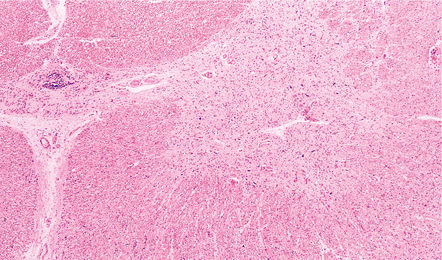

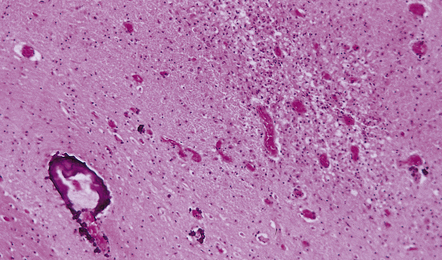

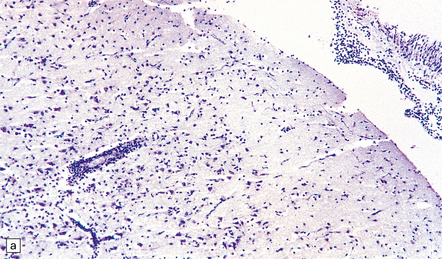

Since aseptic meningitis is by definition benign, reports of the neuropathologic findings are uncommon. Occasionally, patients with aseptic meningitis die as a result of a concurrent systemic illness (e.g. viral myocarditis). Histologic examination of the CNS then reveals a scanty infiltrate of lymphocytes in the meninges, in the perivascular space surrounding some of the superficial cortical blood vessels (Fig. 12.1), and in the choroid plexus.

POLIOMYELITIS

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Acute phase

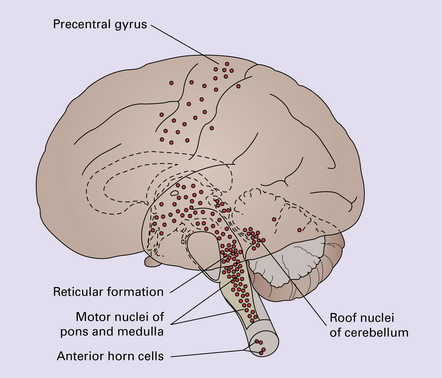

The extent of histologic involvement almost always exceeds that predicted by the clinical manifestations. The distribution of lesions is variable. The spinal gray matter is usually involved, particularly the anterior horn cells. The disease also shows a predilection for the motor nuclei in the pons and medulla, the reticular formation, and deep cerebellar nuclei (Fig. 12.2). Apart from the precentral gyrus, the cerebral cortex is usually spared.

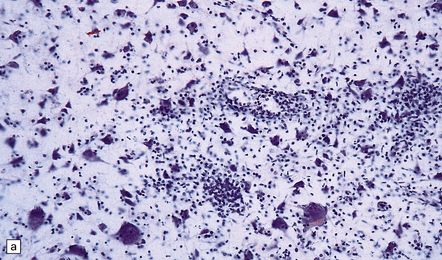

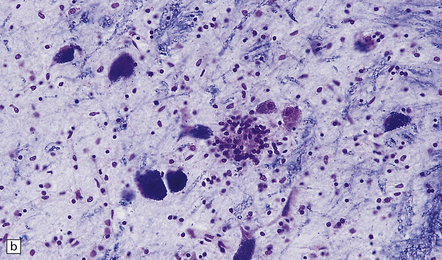

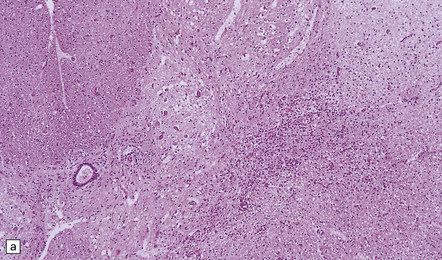

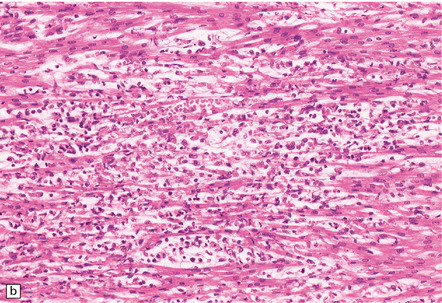

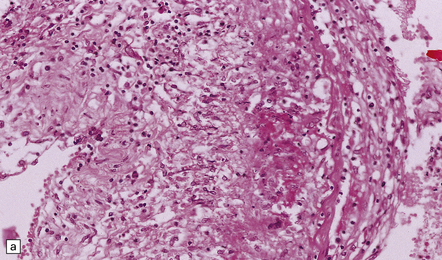

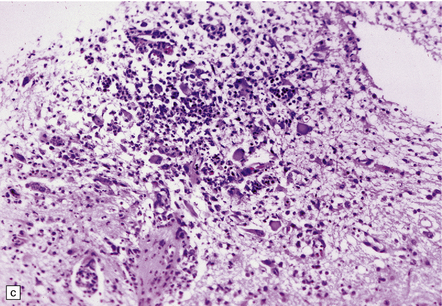

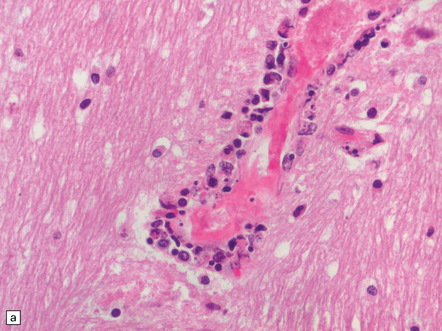

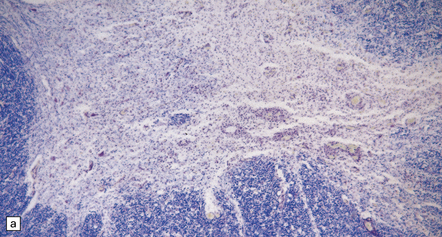

There is intense inflammation in the leptomeninges and affected gray matter (Fig. 12.3). Neutrophils are found initially, but lymphocytes soon predominate. Lymphocytic cuffing of blood vessels is a conspicuous feature.

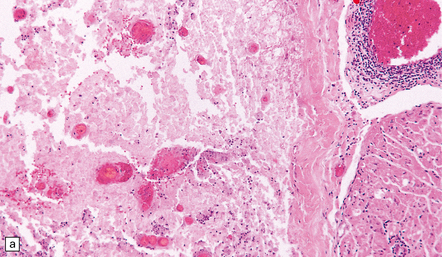

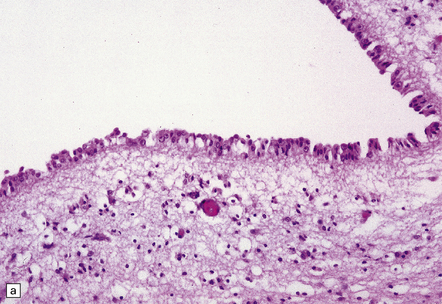

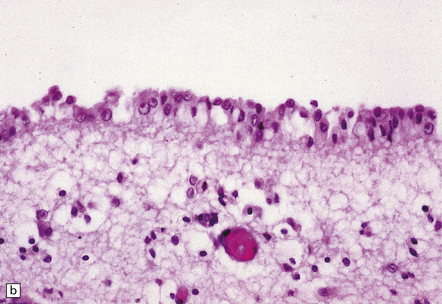

12.3 Poliomyelitis.

(a) and (b) show mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the spinal gray matter in coxsackievirus poliomyelitis. (Courtesy of Dr David Hilton, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, UK.)

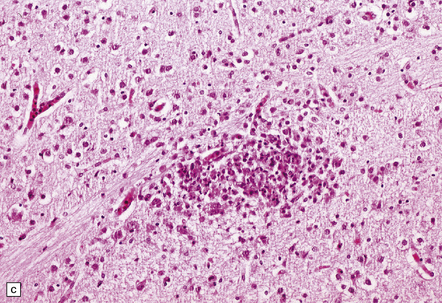

The histologic hallmark of the viral infection of neurons is neuronophagia (aggregation of microglia and macrophages around dead neurons, Fig. 12.4). Clusters of microglia (microglial nodules) mark the sites of destroyed neurons for several weeks after their resorption.

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Chronic phase

Examination of the affected regions shows an obvious loss of motor neurons (Fig. 12.5) and atrophy and fibrosis of anterior nerve roots. There may be scanty residual inflammation. These changes apart, the parenchyma of the affected spinal cord or brain stem is usually remarkably well preserved.

NEONATAL ENTEROVIRAL ENCEPHALITIS

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

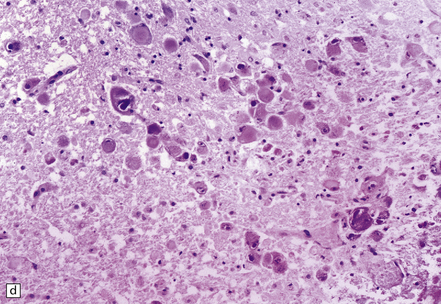

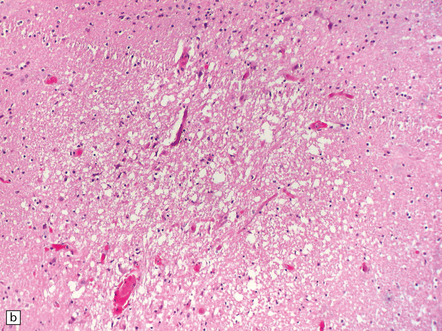

The appearances differ from those in older children and adults. Although the CNS lesions consist of infiltrates of lymphocytes, macrophages and microglia and are usually centered mainly on the gray matter of the brain stem and spinal cord, the white matter is often affected, the lesions may be necrotizing or hemorrhagic, and foci of cerebellar and cerebral inflammation are common (Fig. 12.6).

12.6 Neonatal enteroviral infections often cause destructive infection of multiple organs, and although the CNS disease is predominantly a polioencephalomyelitis, the white matter may also be involved.

(a) Neonatal coxsackievirus B3 infection of the liver has caused extensive panlobular necrosis. (b) There is also myocarditis, with extensive infiltration by mononuclear inflammatory cells. (c) A cluster of lymphocytes, macrophages, and microglia is present in the tegmentum of the pons. (d) Inflammatory cell infiltrates are present both in the white matter (arrow) and the superficial part of the granule cell layer (arrowheads) in the cerebellum.

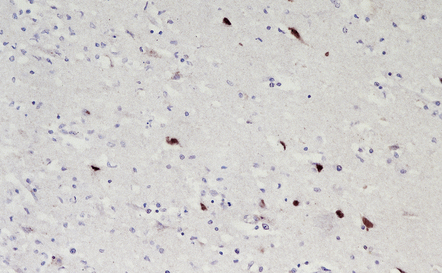

HERPESVIRUS INFECTIONS

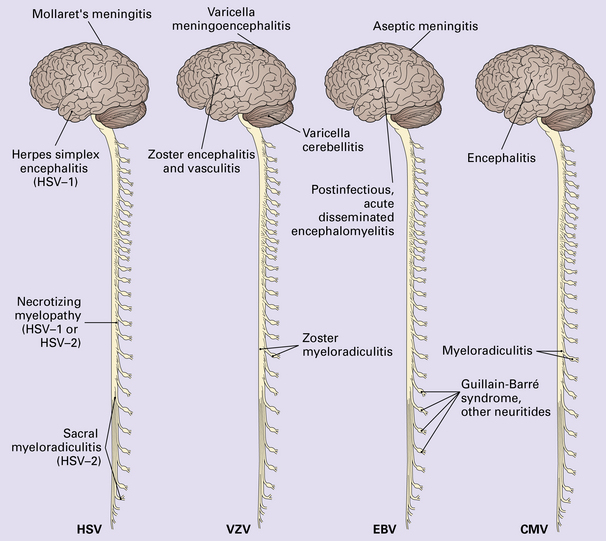

The herpesviruses are relatively large, enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses. The group includes several that are human pathogens and can cause CNS disease (Fig. 12.7), including herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human herpesvirus 6. The simian herpesvirus, B virus, can also infect humans and cause CNS disease. When these viruses invade the CNS they tend to cause necrotizing destruction of both gray and white matter (i.e. panencephalitis or panmyelitis).

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS INFECTION

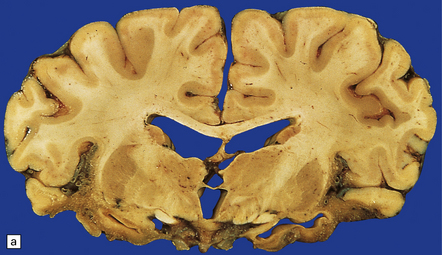

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

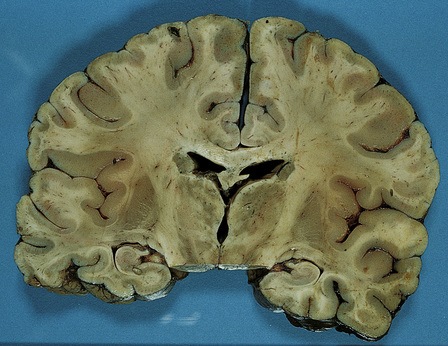

Acute phase

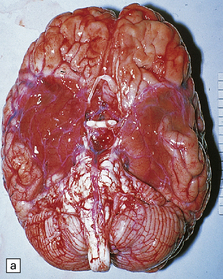

Most cases show obvious congestion and hemorrhagic necrosis involving the temporal lobes (Fig. 12.9) and, to a greater or lesser extent, the insulae, cingulate gyri, and posterior orbital frontal cortex (Fig. 12.9). The lesions are often somewhat asymmetric. Occasionally, in very early disease, the brain may appear macroscopically normal. In contrast, in patients dying some weeks after the onset of disease the liquefactive necrosis in these regions will have progressed to cavitation and atrophy.

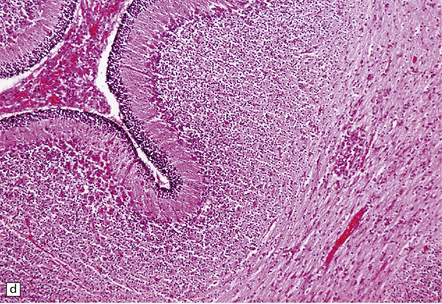

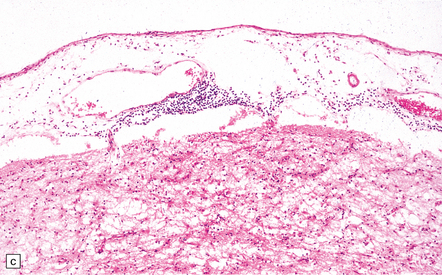

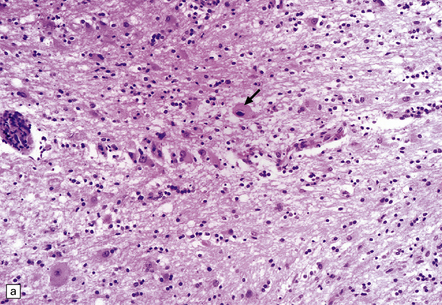

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Acute phase

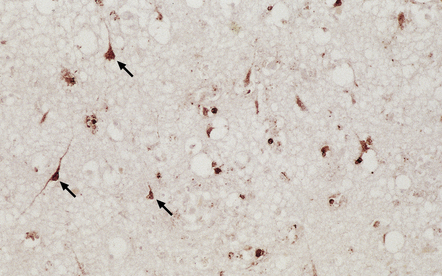

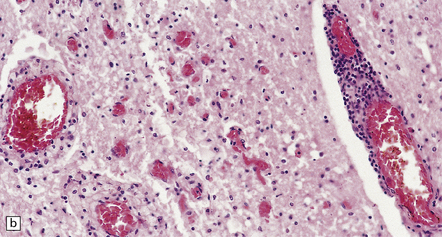

The earliest lesions contain relatively scanty parenchymal inflammation, although there are moderate numbers of lymphocytes and macrophages in the overlying leptomeninges (Fig. 12.10). The lesions extend from the pial surface through the cerebral cortex and into the white matter. The affected neurons, glia, and endothelial cells tend to have slightly hypereosinophilic cytoplasm. Many of the nuclei are pyknotic or disintegrating; others contain homogeneous eosinophilic inclusions (Fig. 12.10), some surrounded by an irregular rim of condensed marginated chromatin. Clumps of eosinophilic inclusion material may also be visible in the cytoplasm. Inclusions are usually best seen in cells towards the edge of lesions.

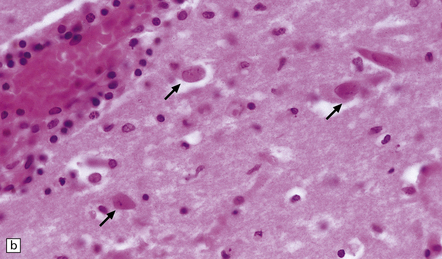

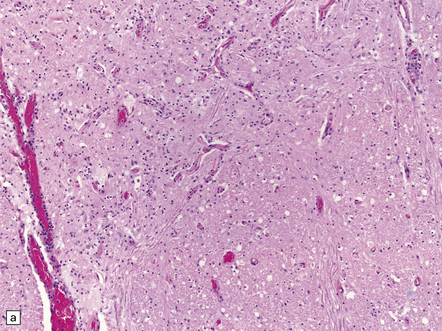

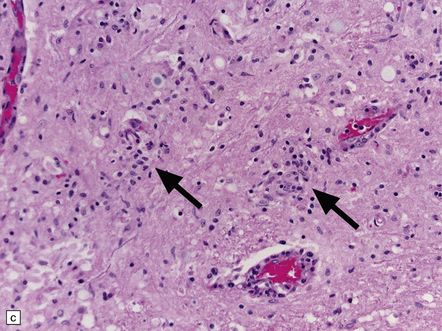

12.10 Early HSE.

(a) Meningeal, perivascular, and scanty parenchymal inflammation. (b) This section shows scanty perivascular inflammation and scattered cells containing viral inclusions (arrows). (c) Towards the edge of the affected region of the temporal lobe, intranuclear viral inclusions (arrow) are visible.

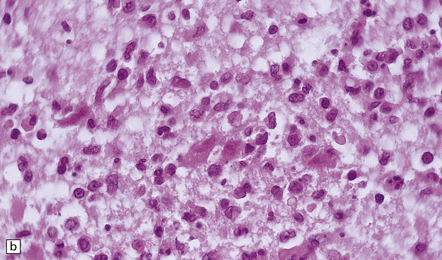

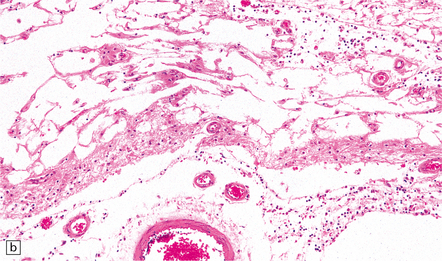

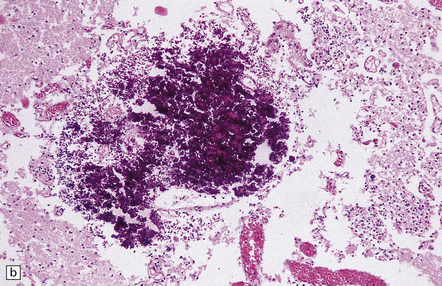

Most lesions are usually at a more advanced stage, containing sheets of necrotic cells, foci of hemorrhage, and an intense perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages (Fig. 12.11). There may be neuronophagia and, later, microglial nodules. Nuclear inclusions are sparse at this stage.

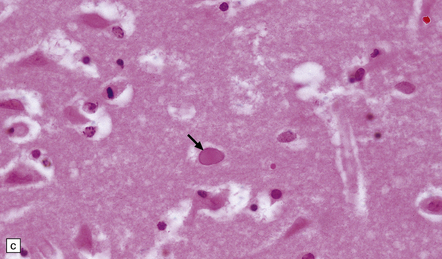

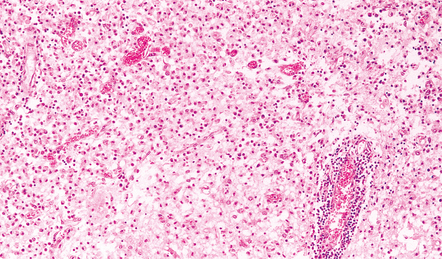

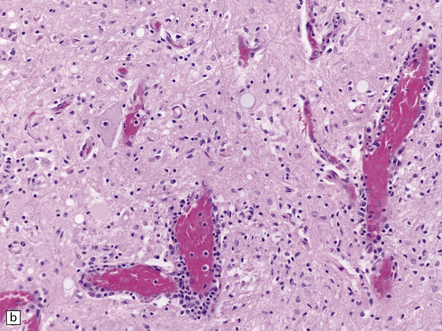

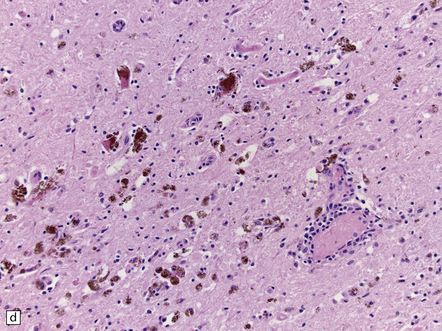

12.11 Necrotizing inflammation in HSE.

Sheets of foamy macrophages and perivascular cuffing by lymphocytes in a case of HSE.

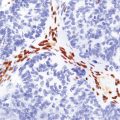

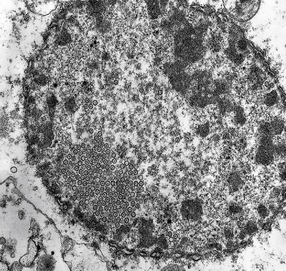

Herpesvirus nucleocapsid particles are approximately 100 nm in diameter and may be seen within the nuclei of infected cells by electron microscopy (Fig. 12.12). Viral antigen is readily demonstrable by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 12.13) for up to approximately 3 weeks after the onset of encephalitis, and viral DNA can be detected in frozen or paraffin sections by in situ hybridization (Fig. 12.14) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification with suitable primers.

12.12 Ultrastructural appearance of HSV.

Electron micrograph showing intranuclear herpesvirus nucleocapsid particles.

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Chronic phase

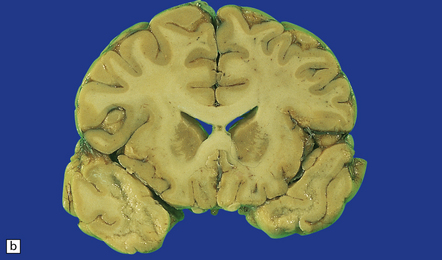

In long-term survivors of untreated or unsuccessfully treated herpes encephalitis, affected parts of the brain are shrunken and cavitated and show yellow-brown discoloration (Fig. 12.15).

12.15 ‘Burnt out’ HSE.

(a) Marked atrophy and yellow-brown discoloration affect the temporal lobes and insulae. (b) Cavitated temporal lobe in a long-term survivor of HSE. (c) Scattered aggregates of lymphocytes persist in the meninges or brain parenchyma for many years. Note also the cortical gliosis and microcystic change.

The normal gray and white matter is replaced by cavitated glial scar tissue (Fig. 12.15). Occasional clusters of lymphocytes are still seen in the meninges and brain parenchyma (Fig. 12.15).

ATYPICAL HERPES SIMPLEX ENCEPHALITIS

In occasional patients, HSE predominantly involves the brain stem or follows a more subacute clinical course than usual (Fig. 12.16). Although the likelihood of developing HSE is probably not increased by immunosuppression, immunosuppression predisposes to atypical forms of the disease.

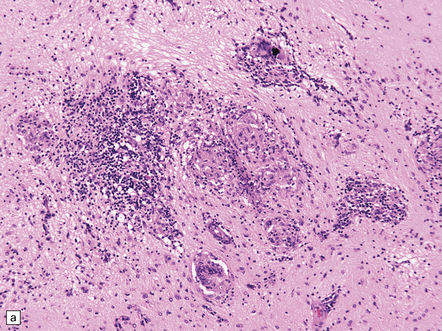

CHRONIC GRANULOMATOUS HERPES SIMPLEX ENCEPHALITIS

Very rarely, children who have experienced an otherwise typical attack of acute herpes encephalitis develop focal or multifocal chronic granulomatous encephalitis, sometimes after an intervening symptom-free period of months or years. Histology reveals a patchy cortical and leptomeningeal infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells and scattered, well-circumscribed granulomas that contain epithelioid macrophages and giant cells, with surrounding lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells. Foci of necrosis and mineralization may be prominent. In some patients, HSV DNA or antigen is demonstrable by PCR or immunohistochemistry (Fig. 12.17).

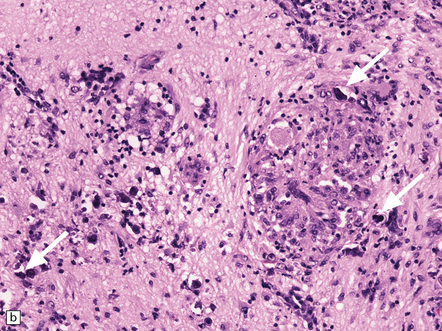

12.17 Chronic granulomatous herpes simplex encephalitis.

(a) Histology of partial temporal lobectomy specimen from a 10-year old boy with chronic granulomatous inflammation complicating herpes simplex virus encephalitis at 4.5 months of age reveals multiple granulomas, some including multinucleated giant cells, with a surrounding infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages. The arrow indicates a focus of mineralization. Postoperatively, HSV-1 DNA and elevated titers of HSV IgM antibodies were detected in the CSF. (b) Higher magnification view of the granulomas and foci of mineralization (arrows).

NECROTIZING MYELOPATHY

Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 can cause this rare disorder. Histology shows extensive necrosis and inflammation involving the spinal gray and white matter (Fig. 12.18). Herpesvirus is usually demonstrable within the cord by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 12.18).

NEONATAL HSV ENCEPHALITIS

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The lesions of HSE in neonates do not show a predilection for any one part of the brain and can involve gray and white matter in the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brain stem (Fig. 12.19). As in adults, the features are of a necrotizing encephalitis, associated with meningeal and parenchymal infiltration by lymphocytes and macrophages. Nuclear inclusions, viral antigen, and DNA are usually demonstrable in abundance, particularly during the first few days of infection.

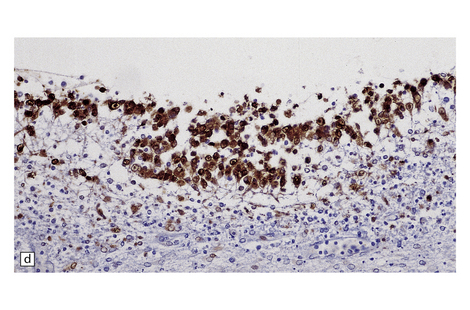

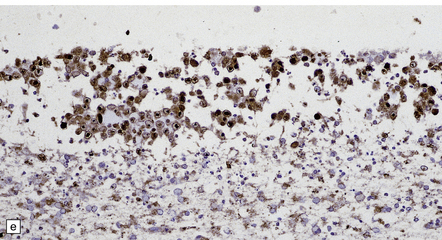

12.19 Neonatal HSV-1 encephalitis.

(a) There is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate at the edge of a zone of necrosis within the cerebral cortex. (b) Immunohistochemistry reveals abundant HSV-1 antigen within the necrotic tissue. (c) There are typical herpesvirus intranuclear inclusions in this case of neonatal HSE. (d) Immunohistochemical demonstration of periventricular HSV-1 infection. (e) Section adjacent to that in (d) showing in situ hybridization of a biotinylated probe for HSV DNA.

VARICELLA-ZOSTER VIRUS (VZV) INFECTION

VZV is the cause of varicella (chickenpox) and herpes zoster (shingles).

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Several patterns are described, including:

multifocal lesions that resemble the demyelinating plaques of multiple sclerosis and predominantly affect cerebral white matter

multifocal lesions that resemble the demyelinating plaques of multiple sclerosis and predominantly affect cerebral white matter

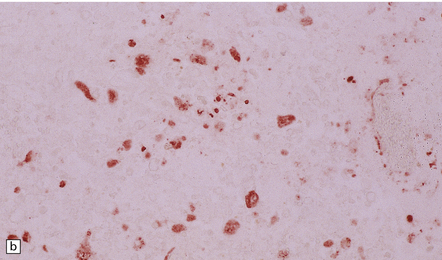

12.20 VZV ventriculitis in a patient with AIDS.

(a) Periventricular edema and scanty lymphocytic inflammation. (b) At higher magnification, intranuclear viral inclusions (arrows) are clearly visible within the ependyma.

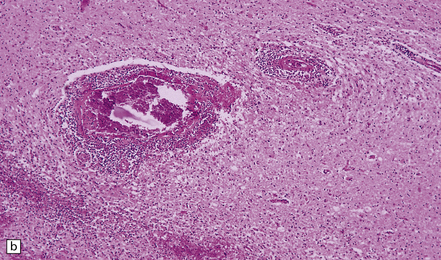

ZOSTER INTRACRANIAL VASCULOPATHY AND VASCULITIS

A well-recognized, albeit rare complication of ophthalmic zoster is the development of contralateral hemiplegia. Angiography may demonstrate cerebral infarction due to inflammation (which may be granulomatous), focal necrosis, and thrombosis of the ipsilateral internal carotid artery or a major parenchymal artery (Fig. 12.21). In other patients the infarction is due to vasculitis involving smaller intracerebral arteries (Fig. 12.21).

12.21 Zoster vasculitis.

(a) Fibrinoid necrosis in the wall of the posterior cerebral artery in VZV infection. This is associated with an infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and multinucleated cells. (b) Infarct in the basal ganglia due to necrotizing vasculitis in a patient with ophthalmic zoster.

FETAL AND NEONATAL INFECTION

Maternal varicella during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy is occasionally complicated by varicella embryopathy, a syndrome of limb hypoplasia, CNS abnormalities (cerebral cortical atrophy, microcephaly, or hydrocephalus), cicatricial skin lesions, and ocular defects (chorioretinitis, cataracts, microphthalmia, optic atrophy). Neuropathologic examination usually reveals foci of cystic degeneration, glial scarring, and microcalcification, but no viral inclusions or antigen. There may be inflammatory infiltrates. Very rarely, there is evidence of active necrotizing infection with viral inclusions and antigen (Fig. 12.22). Fetal infection after 20 weeks of gestation tends to be subclinical but can lead to infantile zoster. Neonatally acquired varicella is usually a severe infection with multiple organ involvement.

EPSTEIN–BARR VIRUS (EBV) INFECTION

EBV may be associated with several peripheral nervous system disorders, including Guillain–Barré syndrome, mononeuritis, and polyneuritis (see Fig. 12.7). CNS complications of EBV infection are much less common and include aseptic meningitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and an acute cerebellitis resembling that associated with VZV. Rarely, the virus causes an encephalitis or myelitis, which may be combined with peripheral neurologic manifestations of infection. Most patients make a good recovery.

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS (CMV) INFECTION

CMV ENCEPHALITIS AND MYELORADICULITIS

Although CMV may cause encephalitis and myeloradiculitis, these complications of infection are uncommon in patients with normal immune function. Much of the literature on CMV encephalitis and myeloradiculitis concerns patients with AIDS (see Chapter 13), in whom several patterns of infection may occur (see below). The majority (~90%) of patients with AIDS and CMV encephalitis also have CMV retinitis; conversely, ~40% of those with CMV retinitis also have CMV encephalitis. Although CMV retinitis usually responds well to ganciclovir or foscarnet, these agents do not prevent the development of CMV encephalitis. The development of symptoms of CMV encephalitis (i.e. impaired mentation, confusion, disorientation, and, in some patients, nystagmus and cranial nerve palsies) carries a poor prognosis in patients with AIDS.

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

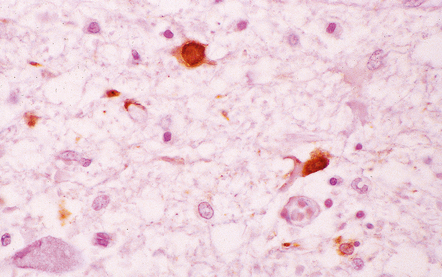

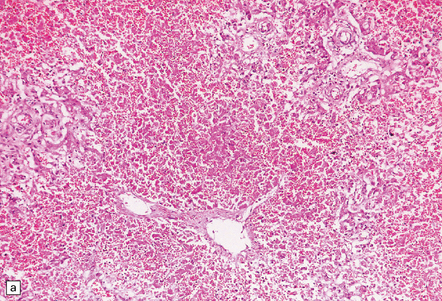

Several patterns are described (Fig. 12.23):

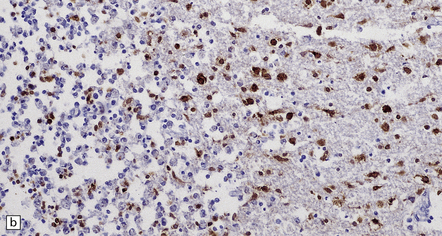

12.23 CMV encephalitis and myelitis in patients with AIDS.

(a) Low-grade, non-necrotizing encephalitis, with scattered cytomegalic inclusion cells (arrow) in the white matter. (b) and (c) illustrate examples of more severe encephalitis, with moderate (b) and more severe (c) white matter damage. Apoptotic bodies (arrows) containing fragments of nuclear DNA are particularly prominent in (b). In (c) there is an associated mixed inflammatory infiltrate. (d) CMV myeloradiculitis, with numerous cytomegalic inclusion cells in the spinal white matter.

low-grade encephalitis, with cytomegalic inclusion cells, usually but not always within microglial nodules

low-grade encephalitis, with cytomegalic inclusion cells, usually but not always within microglial nodules

encephalitis with inclusions that are predominantly within microvascular endothelium

encephalitis with inclusions that are predominantly within microvascular endothelium

necrotizing encephalitis, with large cystic foci resembling infarcts

necrotizing encephalitis, with large cystic foci resembling infarcts

ventriculoencephalitis, with hemorrhagic necrosis of periventricular brain tissue

ventriculoencephalitis, with hemorrhagic necrosis of periventricular brain tissue

CMV infection of the CNS is further discussed and illustrated under HIV infection (see Chapter 13).

CONGENITAL CMV INFECTION

This is the commonest of the known intrauterine viral infections, affecting 0.2–2.2% of live births.

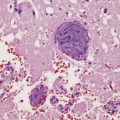

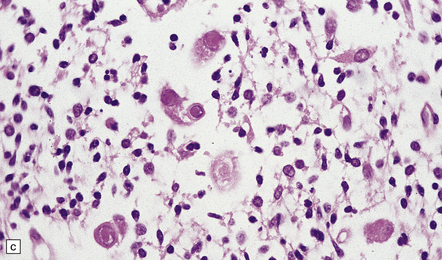

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The neuropathologic features are of a necrotizing encephalitis or ventriculoencephalitis with infiltration by lymphocytes and macrophages, microglial nodules, and typical cytomegalic inclusion cells (Fig. 12.24). Neurons, glia, and endothelial cells may be infected. Immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization reveals that many more cells than show cytomegalic change are infected by virus.

12.24 Congenital CMV encephalitis.

(a) Note the ventricular dilatation and periventricular calcification. (Courtesy of Dr Helen Porter, Bristol Children’s Hospital, UK.) (b) Large focus of periventricular calcification due to CMV encephalitis. (c) Scattered cytomegalic inclusion cells are seen within the germinal matrix. (d) Immunohistochemical demonstration of CMV in scattered cells in the disrupted basal ganglia. Not all of the virus-containing cells have a cytomegalic appearance.

PARAMYXOVIRUSES

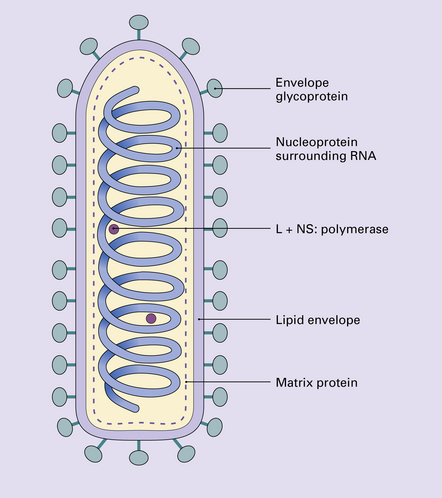

This family includes mumps virus, measles virus, Hendra virus, and Nipah virus (Figs 12.25, 12.26).

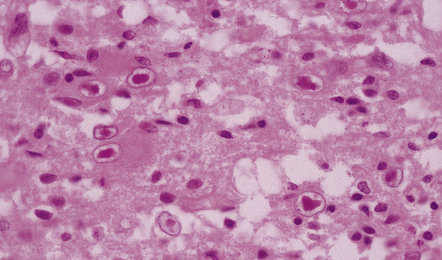

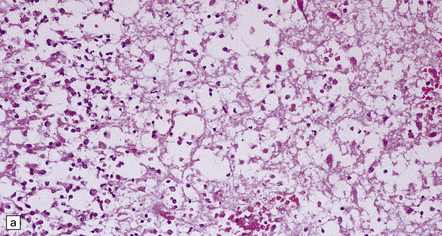

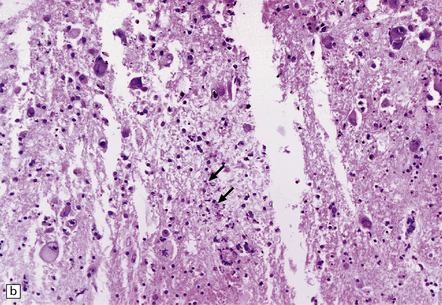

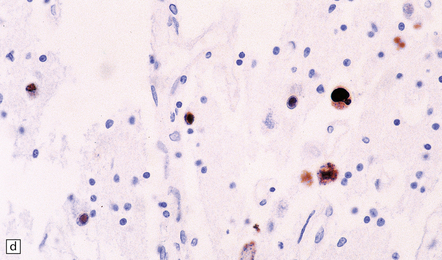

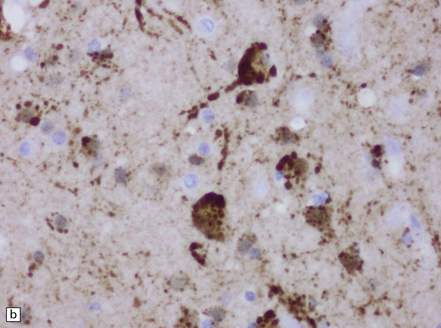

12.25 Acute Nipah encephalitis.

(a) The virus infects endothelial cells, causing necrosis and thrombosis of small blood vessels, including those in the brain. (b) The microangiitis, vascular thrombosis and spread of virus to adjacent neurons produce foci of parenchymal brain necrosis, as illustrated here. (Images courtesy of Dr K T Wong, University of Malaya.)

12.26 Relapsing Nipah encephalitis.

In these cases, there is more abundant virus within the brain, foci of necrosis tend to be larger, sometimes taking the form of concentric bands. (a) Neurons may contain eosinophilic nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions (the arrows indicate two cytoplasmic viral inclusions). (b) There is abundant viral antigen within the infected neurons, shown here by immunoperoxidase labeling. (Images courtesy of Dr K T Wong, University of Malaya.)

Mumps virus is one of the commoner causes of aseptic meningitis (see Table 12.2). Rarely, mumps is complicated by the development of transverse myelitis or acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (Chapter 20).

Mumps virus is one of the commoner causes of aseptic meningitis (see Table 12.2). Rarely, mumps is complicated by the development of transverse myelitis or acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (Chapter 20).

Measles can cause aseptic meningitis or, much less frequently, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (Chapter 20). It is also responsible for two rare, subacute or chronic neurological diseases, measles inclusion body encephalitis and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, that are considered in Chapter 13.

Measles can cause aseptic meningitis or, much less frequently, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (Chapter 20). It is also responsible for two rare, subacute or chronic neurological diseases, measles inclusion body encephalitis and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, that are considered in Chapter 13.

Hendra virus, first identified in 1994 in Australia, is a very rare cause of human encephalitis. The natural hosts are species of Pteropid (fruit bat). Horses are the intermediate hosts. The encephalitis may be part of an acute systemic illness, in which the virus causes vasculitis involving lung, kidney, brain and other organs, as well as necrotizing neuronal infection. Relapse, with severe necrotizing panencephalitis, has been reported months after resolution of the initial clinical illness.

Hendra virus, first identified in 1994 in Australia, is a very rare cause of human encephalitis. The natural hosts are species of Pteropid (fruit bat). Horses are the intermediate hosts. The encephalitis may be part of an acute systemic illness, in which the virus causes vasculitis involving lung, kidney, brain and other organs, as well as necrotizing neuronal infection. Relapse, with severe necrotizing panencephalitis, has been reported months after resolution of the initial clinical illness.

Nipah virus (now placed with Hendra virus in a new genus, Henipavirus) was identified as the cause of outbreaks of encephalitis in Malaysia and Singapore between 1997 and 1999. Subsequent outbreaks have occurred in Bangladesh and India. As for Hendra virus, the natural hosts are species of Pteropid. In most human outbreaks, pigs have been the intermediate hosts. Close proximity of pigs and humans in affected populations has probably been critical in facilitating pig to human transmission. In man, infection may be asymptomatic or manifest with ’flu-like symptoms but can also cause a severe vasculitic illness, most pronounced within the brain but also affecting heart, kidney, and lung. The virus infects endothelial cells, causing formation of occasional syncytia, endothelial necrosis, thrombosis and parenchymal necrosis. In the brain, infection also spreads to adjacent neurons. Some patients have suffered from relapses of encephalitis after resolution of the acute episode. In these cases, foci of necrosis tend to be larger, some form concentric bands, and some may become confluent. Viral nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions, antigen and RNA can be demonstrated within neurons in affected regions.

Nipah virus (now placed with Hendra virus in a new genus, Henipavirus) was identified as the cause of outbreaks of encephalitis in Malaysia and Singapore between 1997 and 1999. Subsequent outbreaks have occurred in Bangladesh and India. As for Hendra virus, the natural hosts are species of Pteropid. In most human outbreaks, pigs have been the intermediate hosts. Close proximity of pigs and humans in affected populations has probably been critical in facilitating pig to human transmission. In man, infection may be asymptomatic or manifest with ’flu-like symptoms but can also cause a severe vasculitic illness, most pronounced within the brain but also affecting heart, kidney, and lung. The virus infects endothelial cells, causing formation of occasional syncytia, endothelial necrosis, thrombosis and parenchymal necrosis. In the brain, infection also spreads to adjacent neurons. Some patients have suffered from relapses of encephalitis after resolution of the acute episode. In these cases, foci of necrosis tend to be larger, some form concentric bands, and some may become confluent. Viral nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions, antigen and RNA can be demonstrated within neurons in affected regions.

RUBELLA ENCEPHALITIS

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Microscopically, the ‘expanded’ rubella syndrome may be associated with active meningoencephalitis. Much more commonly, histology reveals only chronic lesions, consisting of vascular and parenchymal mineralization, particularly in the basal ganglia and thalamus (Fig. 12.27).

RABIES

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The brain and spinal cord may appear swollen, but are usually macroscopically normal.

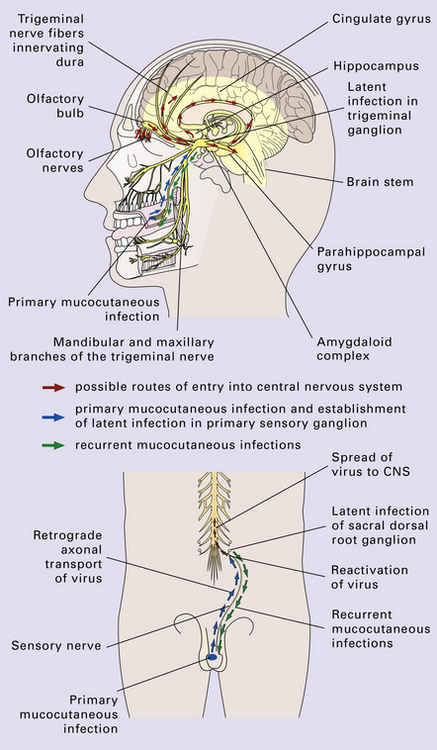

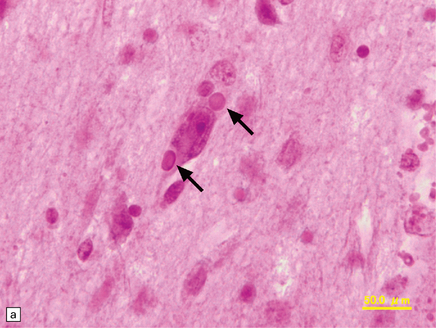

Microscopically, the appearances are of a widespread polioencephalomyelitis. The classic histologic feature is the presence of Negri bodies, which are sharply delineated, round or oval, eosinophilic inclusions in the neuronal cytoplasm (Fig. 12.29). Some neurons contain less well-defined (although ultrastructurally similar) eosinophilic inclusions, termed lyssa bodies. There may occasionally be coarse vacuolation of the cytoplasm of infected neurons. The inclusions can occur in most parts of the CNS, but tend to be easiest to find in Purkinje cells, hippocampal pyramidal cells, and brain stem nuclei.

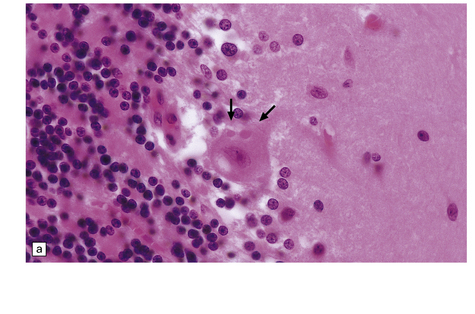

12.29 Rabies encephalitis.

(a) This section shows a Purkinje cell containing two Negri bodies (arrows). Note the absence of inflammation. (b) Cluster of microglia (arrowheads) in the parahippocampal gyrus. One of the remaining neurons contains a Negri body (arrow). (c) The red immunolabeling product highlights the abundant rabies virus antigen in the cytoplasm of infected Purkinje cells. (Courtesy of Professor Francoise Gray, Hôpital Raymond Poincare, Paris.)

Although there are usually leptomeningeal and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates and neuronophagia, there may be a striking disparity between the abundance of virus and the limited degree of inflammation. The clusters of microglia that remain after neuronal destruction are known as Babès’ nodules (Fig. 12.29).

Immunostaining of virus usually shows it to be much more abundant than is evident on conventional microscopy (Fig. 12.29). Virus can be identified by immunofluorescence in corneal cells and in cutaneous nerve fibers. The disease can therefore be confirmed by examining corneal impressions or nuchal skin biopsies.

ARBOVIRUS INFECTIONS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The brain tends to be moderately congested and swollen (Fig. 12.30). There may be petechial hemorrhages. The most severely affected parts of the nervous system are:

12.30 Coronal slice through the brain in a case of Japanese encephalitis.

The brain is congested and there is mottled dusky discoloration of the thalamus and upper part of the midbrain. (Courtesy of Professor Francesco Scaravilli, Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London.)

Western and Eastern equine encephalitis – basal ganglia, thalamus, brain stem

Western and Eastern equine encephalitis – basal ganglia, thalamus, brain stem

St Louis encephalitis – midbrain, thalamus

St Louis encephalitis – midbrain, thalamus

Japanese encephalitis – thalamus, substantia nigra, brain stem, spinal cord

Japanese encephalitis – thalamus, substantia nigra, brain stem, spinal cord

West Nile fever – thalamus, cerebellum, substantia nigra, pons, medulla, spinal cord. Predominantly gray matter involvement. Abundant viral antigen demonstrable in neurons.

West Nile fever – thalamus, cerebellum, substantia nigra, pons, medulla, spinal cord. Predominantly gray matter involvement. Abundant viral antigen demonstrable in neurons.

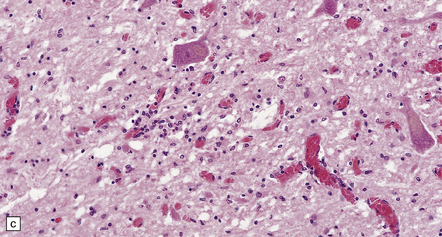

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Histology reveals leptomeningeal, perivascular, and parenchymal infiltration, predominantly by lymphocytes and microglia or macrophages (Figs 12.31, 12.32). Affected gray matter regions contain perivascular cuffs of mononuclear inflammatory cells, especially lymphocytes, perivascular hemorrhages, and microglial nodules, often surrounding degenerating neuronal cell bodies (neuronophagia) (Fig. 12.32). The perivascular inflammation in the white matter is associated with focal necrosis of myelinated fibers. Other features include thrombosed small blood vessels and, rarely, large regions of necrosis.

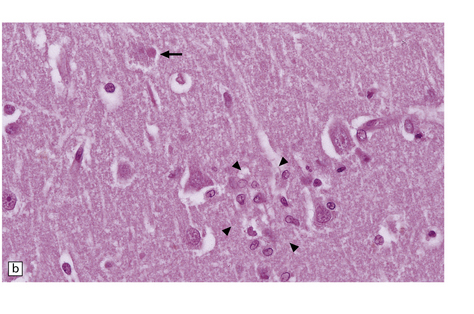

12.31 Inflammatory lesions in the cervical cord in Japanese encephalitis.

(a) There is extensive destruction of anterior horn cells and infiltration of the gray matter by mononuclear inflammatory cells. (b) Higher magnification of a section stained with hematoxylin and eosin shows accumulation of foamy macrophages and perivascular cuffing by lymphocytes. (c) Cluster of lymphocytes and macrophages within the gray matter in a better-preserved part of the spinal cord. (Courtesy of Professor Francesco Scaravilli, Institute of Neurology, London.)

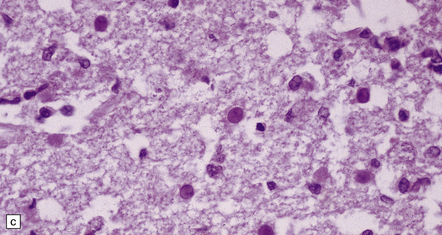

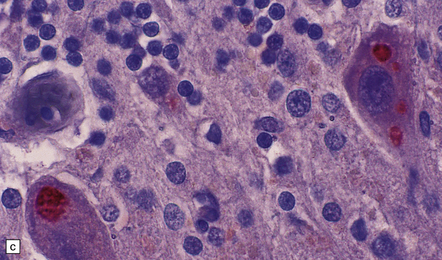

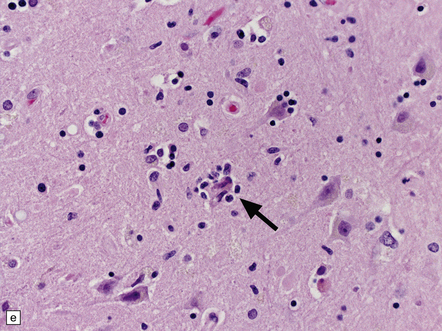

12.32 West Nile virus infection.

(a) One of the commoner manifestations of West Nile virus infection of the CNS is polioencephalitis. In this section, through part of the infected lumbar spinal cord, the anterior horn (upper left part of image) is hypercellular, with perivascular and parenchymal infiltrates of mononuclear inflammatory cells. In contrast, the white matter appears relatively normal. This poliomyelitic picture resembles that sometimes seen in encephalomyelitis produced by another flavivirus, Japanese encephalitis (see Fig. 12.30), as well, of course, as in infections caused by polioviruses and some other members of the Enterovirus family. (b) The perivascular inflammatory infiltrates are more obvious at higher magnification. (c) The arrows indicate clusters of microglia and macrophages marking sites of neuronophagia of anterior horn cells. (d) The substantia nigra is often severely affected in West Nile encephalitis. In this case there has been extensive destruction of nigral neurons, leaving clusters of pigment-laden macrophages. (e) The arrow indicates an example of neuronophagia in the temporal neocortex in a patient with West Nile encephalitis. (Sections courtesy of Dr C Wiley, University of Pittsburgh.)

REFERENCES

Irani, D.N. Aseptic meningitis and viral myelitis. Neurol Clin.. 2008;26:635–655. [vii–viii].

Kumar, R. Aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management. Indian J Pediatr.. 2005;72:57–63.

Lee, B.E., Davies, H.D. Aseptic meningitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis.. 2007;20:272–277.

Lewthwaite, P., Perera, D., Ooi, M.H., et al. Enterovirus 75 encephalitis in children, southern India. Emerg Infect Dis.. 2010;16:1780–1782.

Muir, P., van Loon, A.M. Enterovirus infections of the central nervous system. Intervirology.. 1997;40:153–166.

Ooi, M.H., Wong, S.C., Lewthwaite, P., et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, and management of enterovirus 71. Lancet Neurol.. 2010;9:1097–1105.

Rhoades, R.E., Tabor-Godwin, J.M., Tsueng, G., et al. Enterovirus infections of the central nervous system. Virology.. 2011;411:288–305.

Adamo, M.A., Abraham, L., Pollack, I.F. Chronic granulomatous herpes encephalitis: a rare entity posing a diagnostic challenge. J Neurosurg Pediatr.. 2011;8:402–406.

Amlie-Lefond, C., Jubelt, B. Neurologic manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep.. 2009;9:430–434.

Baringer, J.R. Herpes simplex infections of the nervous system. Neurol Clin.. 2008;26:657–674. [viii].

Berger, J.R., Houff, S. Neurological complications of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Arch Neurol.. 2008;65:596–600.

Kimberlin, D. Herpes simplex virus, meningitis and encephalitis in neonates. Herpes.. 2004;11:65A–76A.

Love, S., Koch, P., Urbach, H., et al. Chronic granulomatous herpes simplex encephalitis in children. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 2004;63:1173–1181.

Steiner, I., Kennedy, P.G., Pachner, A.R. The neurotropic herpes viruses: herpes simplex and varicella-zoster. Lancet Neurol.. 2007;6:1015–1028.

Tyler, K.L. Update on herpes simplex encephalitis. Rev Neurol Dis.. 2004;1:169–178.

Tyler, K.L. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: encephalitis and meningitis, including Mollaret’s. Herpes.. 2004;11:57A–64A.

Volpi, A. Severe complications of herpes zoster. Herpes. 2007;14:S35–S39.

Volpi, A., Stanberry, L. Herpes zoster in immunocompromised patients. Herpes.. 2007;14:31.

Whitley, R. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis.. 2004;17:243–246.

Vigant, F., Lee, B. Hendra and Nipah infection: pathology, models and potential therapies. Infect Disord Drug Targets.. 2011;11:315–336.

Wong, K.T. Emerging epidemic viral encephalitides with a special focus on henipaviruses. Acta Neuropathol (Berl).. 2010;120:317–325.

Wong, K.T., Ong, K.C. Pathology of acute henipavirus infection in humans and animals. Patholog Res Int. 2011. [Epub:21961078].

Best, J.M. Rubella. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med.. 2007;12:182–192.

Dwyer, D.E., Robertson, P.W., Field, P.R. Broadsheet: Clinical and laboratory features of rubella. Pathology.. 2001;33:322–328.

Hemachudha, T., Wacharapluesadee, S., Laothamatas, J., et al. Rabies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep.. 2006;6:460–468.

Laothamatas, J., Wacharapluesadee, S., Lumlertdacha, B., et al. Furious and paralytic rabies of canine origin: neuroimaging with virological and cytokine studies. J Neurovirol.. 2008;14:119–129.

Leung, A.K., Davies, H.D., Hon, K.L. Rabies: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prophylaxis. Adv Ther.. 2007;24:1340–1347.

Schnell, M.J., McGettigan, J.P., Wirblich, C., et al. The cell biology of rabies virus: using stealth to reach the brain. Nat Rev Microbiol.. 2010;8:51–61.

Warrell, M. Rabies and African bat Lyssavirus encephalitis and its prevention. Int J Antimicrob Agents.. 2010;36:S47–S52.

Das, T., Jaffar-Bandjee, M.C., Hoarau, J.J., et al. Chikungunya fever: CNS infection and pathologies of a re-emerging arbovirus. Prog Neurobiol.. 2010;91:121–129.

Davis, L.E., DeBiasi, R., Goade, D.E., et al. West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease. Ann Neurol.. 2006;60:286–300.

Desai, A., Shankar, S.K., Ravi, V., et al. Japanese encephalitis virus antigen in the human brain and its topographic distribution. Acta Neuropathol (Berl).. 1995;89:368–373.

Gelpi, E., Preusser, M., Garzuly, F., et al. Visualization of Central European tick-borne encephalitis infection in fatal human cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 2005;64:506–512.

Gelpi, E., Preusser, M., Laggner, U., et al. Inflammatory response in human tick-borne encephalitis: analysis of postmortem brain tissue. J Neurovirol.. 2006;12:322–327.

Haglund, M., Gunther, G. Tick-borne encephalitis − pathogenesis, clinical course and long-term follow-up. Vaccine.. 2003;21:S11–S18.

Hollidge, B.S., Gonzalez-Scarano, F., Soldan, S.S. Arboviral encephalitides: transmission, emergence, and pathogenesis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol.. 2010;5:428–442.

Lindquist, L., Vapalahti, O. Tick-borne encephalitis. Lancet.. 2008;371:1861–1871.

Mackenzie, J.S., Gubler, D.J., Petersen, L.R. Emerging flaviviruses: the spread and resurgence of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue viruses. Nat Med.. 2004;10:S98–S109.

Mansfield, K.L., Johnson, N., Phipps, L.P., et al. Tick-borne encephalitis virus – a review of an emerging zoonosis. J Gen Virol.. 2009;90:1781–1794.

Misra, U.K., Kalita, J. Overview: Japanese encephalitis. Prog Neurobiol.. 2010;91:108–120.

Murray, K., Walker, C., Herrington, E., et al. Persistent infection with West Nile virus years after initial infection. J Infect Dis.. 2010;201:2–4.

Murray, K.O., Walker, C., Gould, E. The virology, epidemiology, and clinical impact of West Nile virus: a decade of advancements in research since its introduction into the Western Hemisphere. Epidemiol Infect.. 2011;139:807–817.

Rossi, S.L., Ross, T.M., Evans, J.D. West Nile virus. Clin Lab Med.. 2010;30:47–65.

Solomon, T. Recent advances in Japanese encephalitis. J Neurovirol.. 2003;9:274–283.

Solomon, T., Kneen, R., Dung, N.M., et al. Poliomyelitis-like illness due to Japanese encephalitis virus. Lancet.. 1998;351:1094–1097.

Weaver, S.C., Reisen, W.K. Present and future arboviral threats. Antiviral Res.. 2010;85:328–345.

Solomon, T. Exotic and emerging viral encephalitides. Curr Opin Neurol.. 2003;16:411–418.

Tyler, K.L. Emerging viral infections of the central nervous system: part 2. Arch Neurol.. 2009;66:1065–1074.

Tyler, K.L. Emerging viral infections of the central nervous system: part 1. Arch Neurol.. 2009;66:939–948.

Solomon, T., Willison, H. Infectious causes of acute flaccid paralysis. Curr Opin Infect Dis.. 2003;16:375–381.