91 Acute Compartment Syndromes

Epidemiology

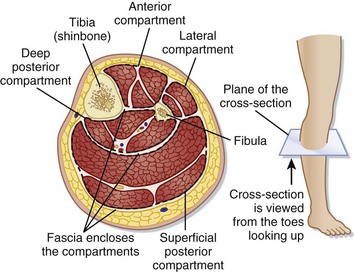

The true incidence of acute compartment syndrome (CS) varies with the inciting event. Almost half of all cases of CS are related to tibia fractures. The incidence of CS with tibia fractures is 1.2% with closed fractures, 6% with open fractures, and as high as 19% with concomitant vascular injury.1,2 The forearm is the second leading site. CS can occur in any contained compartment.

Pathophysiology

CS is a condition of impaired microcirculatory perfusion related to increased interstitial pressure within a closed compartment. CS begins when increased pressure as a result of increased volume within or external pressure compromises microcirculatory perfusion within that space. Once autoregulatory reductions in the arteriovenous gradient are overwhelmed, interstitial pressure will rise above capillary perfusion pressure (normally between 20 and 30 mm Hg in a normotensive patient for most compartments), and tissue ischemia will occur.3 CS is characterized by a self-propagating cycle of impaired perfusion resulting in ischemia, release of osmotically active particles, and edema, which further increase interstitial pressure and diminished perfusion (Fig. 91.1).

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

CS should be on the working list of “worst-case” diagnoses for every patient with musculoskeletal pain. CS may result from either externally applied compressive force or internally expanding force, and a suggestive history should be elicited (Box 91.1). Myofascial causes include long-bone fracture, vascular injury, reperfusion after ischemia, burns, prolonged positioning from a drug overdose or operating procedures, compression from tight casts and dressings (including military antishock trousers), overexertion, hemorrhage, injection of fluid into the compartment, massive intravenous fluid infusions, envenomations, hypothyroidism, and rhabdomyolysis. CS has also been reported with deep vein thrombosis and ruptured Baker cysts (see Box 91.1). High-risk patients with an altered sensorium may be unable to provide an appropriate history. CS usually develops hours after the inciting event and rarely more than 48 hours after the inciting event.

Box 91.1 Causes of Acute Compartment Syndrome

Treatment

Prehospital Management

The affected limb should be placed at the level of the heart. Elevation is contraindicated because it decreases arterial flow, which narrows the arteriovenous pressure gradient and thus worsens ischemia.4 Circumferential bandages should be removed, and casts should be removed or split.5 Because hypotension potentiates CS, it should be corrected with crystalloid or blood products. Supplemental oxygen should be administered routinely to improve tissue oxygenation.6

Hospital Management

Measurement of intracompartmental pressure is not necessary if the diagnosis of acute CS is clinically apparent.7 Equivocal cases may require further evaluation. Multiple methods and devices for measuring compartmental pressure are available. Devices that use a side-ported needle or slit catheter are recommended rather than those using a simple needle.

Normal intracompartmental pressure is in the range of 0 to 10 mm Hg. Pain and paresthesias are common at 20 to 30 mm Hg, and ischemia generally ensues at pressures greater than 30 mm Hg. Many surgeons traditionally consider a measured compartment pressure of 30 mm Hg or higher as an indication for fasciotomy,8 although higher values have been used, especially for the thigh. More recently, some authors have recommended the use of a ΔP value (diastolic blood pressure minus the measured intracompartmental pressure) of less than 30 to 50 mm Hg as an indication for fasciotomy and have found it to be more reliable than an absolute compartment pressure (Box 91.2).

Box 91.2 Management of Acute Compartment Syndrome

Maintain the affected area at the level of the heart.

Reverse hypoperfusion/hypotension.

Maximize oxygenation/administer supplemental oxygen.

Correct coagulopathy if present.

Modify the cast, splint, or dressing if this is the precipitant of the syndrome.

Order antivenom if envenomation is the cause of the syndrome.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Suspect acute compartment syndrome when a patient has severe pain, especially with passive movement, but few other objective physical findings.

Measure compartment pressures when indicated.

Consult the orthopedic or general surgery department.

Treat hypotension and anemia, provide oxygen, and reverse coagulopathy if present.6

The affected compartment should be positioned at the level of the heart.7

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Documentation

Documentation

History: A careful history will include the mechanism, timing, history of paresthesia or weakness, medical conditions that may impair oxygenation or perfusion, coagulopathy or anticoagulation therapy, intravenous drug use, increasing pain, and pain with active or passive movement

Physical examination: Including neurovascular signs, compartment palpation, discoloration, masses, range of motion

Medical decision making: Reasons to pursue or not pursue work-up or consultation

Patient teaching: Patients with significant extremity pain but who do not have clinical evidence of acute compartment syndrome should be counseled to avoid activity, maintain the extremity at the level of the heart, and return if any increase in pain occurs

Special Circumstances

Acute Orbital Compartment Syndrome

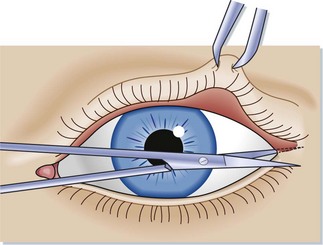

The emergency procedure of choice for loss of visual acuity associated with acute orbital CS is lateral canthotomy and cantholysis of the canthal ligaments (Box 91.3; Figs. 91.2 and 91.3; also see the Tips and Tricks box). Primary indications for lateral canthotomy and cantholysis include intraocular pressure greater than 40 mm Hg with visual loss and proptosis, which may be used as a criterion for an unconscious patients whose visual acuity cannot be determined. Secondary criteria include an afferent pupillary defect, ophthalmoplegia, cherry-red macula, optic nerve head pallor, and severe pain, but these signs are all considered less sensitive or very late.

Tips and Tricks

Lateral Canthotomy and Canthal Ligament Cantholysis Procedures

Lateral Canthotomy

Stabilize the patient’s head and lids.

Anesthetize the lateral canthus with lidocaine with or without epinephrine.

Crush the canthus with a hemostat for 30 to 60 seconds.

Incise the canthus with straight sharp-edged scissors, make a horizontal incision over the crushed canthus, and continue to the bony orbital rim (see Fig. 91.2).

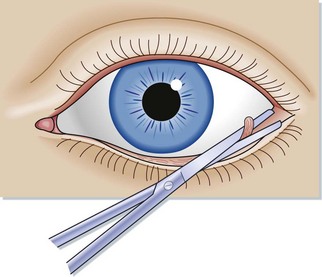

Cantholysis Sweep Technique

Starting lateral to the midline, carefully sweep the lateral edge of the open-faced straight or curved blunt-edged scissors along the palpebral conjunctiva toward the canthotomy incision, with care taken to avoid the orbit and orbital conjunctiva.

The canthal ligament will be identified as the structure along the orbital rim that prevents a completely smooth sweep to the canthotomy incision.

Identify and isolate the ligament with the open scissor blade (see Fig. 91.3).

Carefully maneuver the opposing scissor blade into place while avoiding the globe.

A contraindication to lateral canthotomy is a suspected ruptured globe. In an experimental model, lateral canthotomy/ cantholysis produced a mean decrease in intraocular pressure of 30.4 mm Hg.9 Emergency department personnel should be familiar with and able to perform this procedure in the event that emergency ophthalmology consultation is delayed.

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Abdominal CS is a sudden increase in intraabdominal pressure that results in dysfunction of the respiratory, cardiovascular, and renal systems.10 Normal intraabdominal pressure is 0 to 5 mm Hg. Acute abdominal CS was defined by the 2004 International Abdominal Compartment Syndrome Consensus Definitions Conference Committee as sustained intraabdominal pressure greater than 20 mm Hg that is associated with new organ dysfunction or failure. It is most common after abdominal surgical procedures but can also occur with peritonitis, intraabdominal abscesses, intestinal obstructions, ruptured abdominal aneurysms, acute pancreatitis, intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal hemorrhage, ascites, ovarian tumors, and massive edema following resuscitation.

1 DeLee JC, Stiehl JB. Open tibia fracture with compartment syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;160:175–184.

2 Feliciano DV, Cruse PA, Spjut-Patrinely V, et al. Fasciotomy after trauma to the extremities. Am J Surg. 1988;156:533–536.

3 Matsen FA, III. Compartment syndrome. A unified concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;113:8–14.

4 Wiger P, Styf JR. Effects of limb elevation on abnormally increased intramuscular pressure, blood perfusion pressure, and foot sensation. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:343–347.

5 Garfin SR, Mubarak SJ, Evans KL, et al. Quantification of intracompartmental pressure and volume under plaster casts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:449–453.

6 Wall CJ, Lynch J, Harris IA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of acute limb compartment syndrome following trauma. Aust N Z J Surg. 2010;80:151–156.

7 Tiwari A, Haq AI, Myint F, et al. Acute compartment syndromes. Br J Surg. 2002;89:397–412.

8 McQueen MM, Court-Brown CM. Compartment monitoring in tibial fractures. The pressure threshold for decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:99–104.

9 Yung CW, Moorthy RS, Lindley D, et al. Efficacy of lateral canthotomy and cantholysis in orbital hemorrhage. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;10:137–141.

10 Schein M, Wittman DH, Aprahamian CC, et al. The abdominal compartment syndrome: the physiological and clinical consequences of elevated intra-abdominal pressure. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:745–753.