88

Actinic Keratosis, Basal Cell Carcinoma, and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Introduction

• NMSC typically refers to the keratinocyte carcinomas – i.e. basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) – but can also include rare tumors such as Merkel cell carcinoma (see Chapter 95).

• ~75–80% of NMSCs are BCCs, and up to 25% are SCCs.

• The two most important risk factors for developing NMSC are skin phototype (see Appendix) and UV light exposure (Table 88.1).

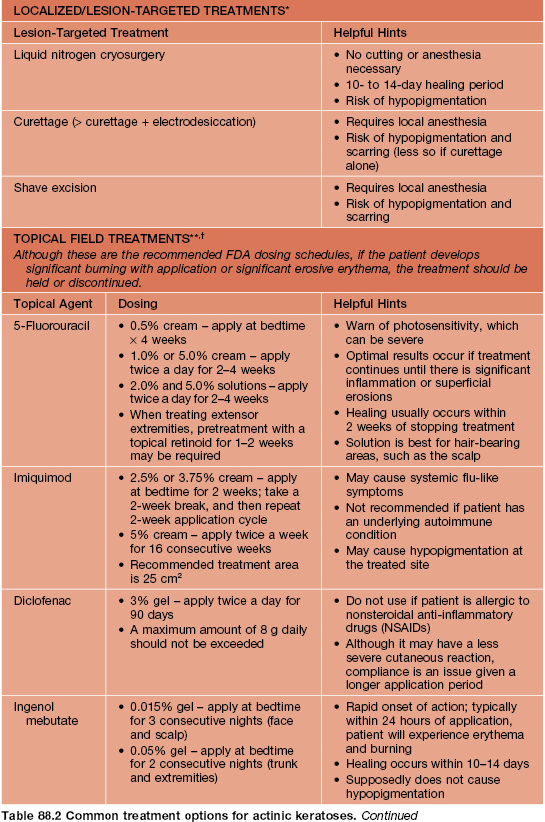

Table 88.1

Risk factors for the development of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs).

* Both SCCs (keratoacanthoma type) and BCCs typically have sebaceous differentiation.

† More often trichoblastomas.

HPV, human papillomavirus.

Actinic Keratoses (AKs)

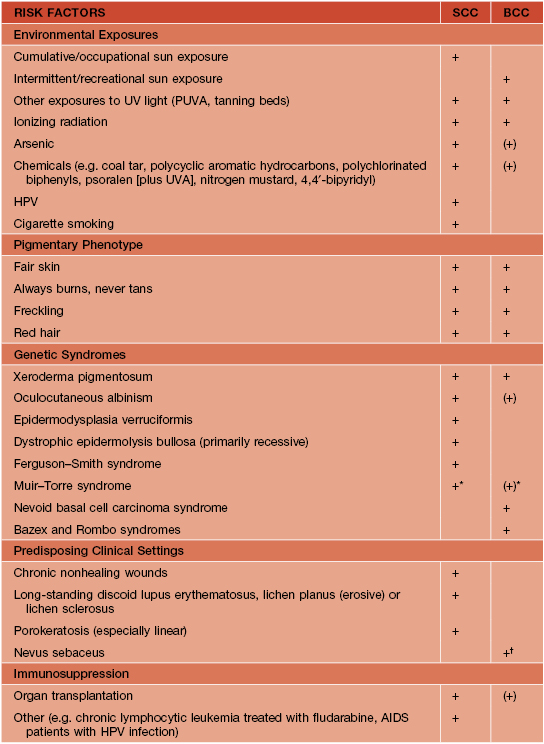

• The atypical keratinocytes are confined to the lower portion of the epidermis (Fig. 88.1).

Fig. 88.1 The histopathologic spectrum of actinic keratosis (AK), SCC in situ, and invasive SCC. A An AK consists of a lower epidermal proliferation of cytologically abnormal keratinocytes; the adnexal epithelium is notably spared. B In SCC in situ, the atypical keratinocytes occupy the entire epidermis and intraepidermal portion of adnexal structures, without invasion into the dermis. C Invasive SCC is distinguished by the extension of the malignant keratinocytes into the dermis. If an invasive SCC is clinically suspected, the biopsy specimen should be deep enough to determine the extent of dermal invasion.

• AKs are one of the most frequently encountered lesions in clinical practice.

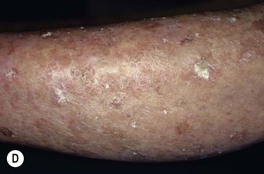

• Classic presentation is a gritty papule with an erythematous base; the associated scale is usually white to yellow in color and feels rough (Fig. 88.2).

Fig. 88.2 Actinic keratoses (AKs). A Multiple AKs on the face of an elderly woman with fair complexion, blue eyes, and moderate to severe photodamage; the AKs vary in size from a few millimeters to more than 1 cm. On the left forehead, the red nodule with slight scale-crust represents a well-differentiated SCC. B Pink-colored atrophic AK with minimal scale on the forehead. C Multiple hypertrophic AKs on the bald scalp with hypopigmentation at sites of previous treatment. D Multiple, large hypertrophic AKs on the shin of an elderly woman; note the thick scale. A, C, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD; B, Courtesy, Iris Zalaudek, MD; D, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Common clinical variants: hypertrophic (referred to as HAK [Fig. 88.2C,D]), pigmented, lichenoid, and atrophic (Fig. 88.2B); in actinic cheilitis, there is scaling and roughness of the lower vermilion lip (see Fig. 13.5).

• DDx: SCC in situ, BCC, lichen planus-like keratosis (LPLK; see Chapter 89), irritated seborrheic keratosis (SK) or verruca vulgaris, and amelanotic melanoma; for thicker lesions (e.g. HAK), invasive SCC; for lesions on extensor extremities, actinic porokeratosis; occasionally, isolated lesions of psoriasis or seborrheic dermatitis may resemble an AK.

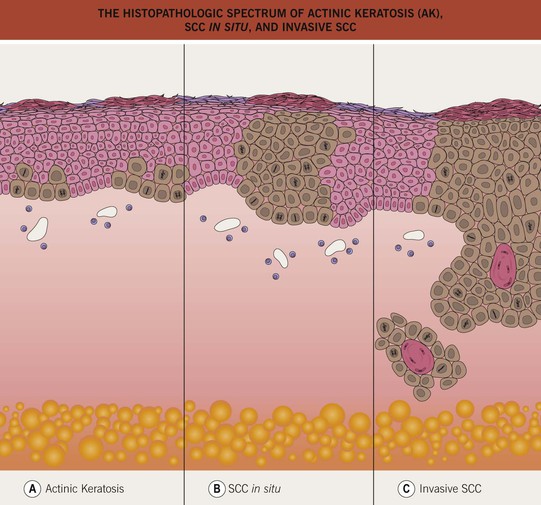

• Rx: localized or lesion-targeted treatments are best for an isolated or limited number of lesions; field treatments are best for more numerous or larger lesions (Table 88.2).

• Prevention is possible with broad-spectrum sunscreens and sun avoidance measures.

SCC In Situ (Bowen’s Disease)

• May arise de novo or from a pre-existing AK; sometimes caused by oncogenic strains of human papillomavirus (HPV, e.g. periungual [see Chapter 66]).

• Keratinocyte atypia is seen throughout the entire epidermis (full-thickness) (see Fig. 88.1) and has the potential to progress to invasive SCC, with an estimated risk of ~3–5% if untreated.

• With the exception of HPV- or arsenic-related SCC in situ, the risk factors for and the locations of SCC in situ are similar to those for AKs (see above and Table 88.1).

• Clinically presents as an erythematous patch or thin plaque with scale (Fig. 88.3); occasionally, the lesions are pigmented.

Fig. 88.3 Squamous cell carcinoma, in situ, Bowen’s type. A Scaly red plaque on the chest with skip areas. B Bright-red, well-demarcated plaque on the proximal nail fold with associated horizontal nail ridging; the possibility of HPV infection needs to be considered. C Dermoscopic examination of a pink scaly plaque of SCC in situ on the chest, with tiny dotted vessels in the upper half of the lesion combined with superficial scales. D Extensive involvement of the finger, which is often misdiagnosed clinically as psoriasis or chronic eczema and therefore treated for years with corticosteroid creams (as was this patient). C, Courtesy, Iris Zalaudek, MD; D, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD.

• Less common sites (may be related to HPV infection): beard area, periungual (see Figs. 88.3B and 58.7) and subungual, anogenital (now referred to as intraepithelial neoplasia, further qualified by anatomic site [see Chapter 60 and Fig. 88.4]); SCC in situ in non-sun-exposed sites may also be related to arsenic exposure.

Fig. 88.4 Squamous cell carcinoma, in situ, of the penis, also known as penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). Formerly called SCC in situ, erythroplasia of Queyrat type. Large eroded erythematous plaque with well-demarcated borders. The lesion began on the shaft of the penis.

• Dx: biopsy; dermoscopy may assist in diagnosis (Fig. 88.3C).

• Rx: tangential excision with curettage or electrodesiccation and curettage (especially for smaller lesions), excision, Mohs micrographic surgery (e.g. head and neck, acrogenital); imiquimod cream and topical 5% fluorouracil (twice daily for a longer period, e.g. 8 weeks) may be used when a surgical approach would prove difficult to perform because of location or extent.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

• An invasive mucocutaneous malignancy arising from keratinocytes; may develop de novo or from precursor AK or SCC in situ (see Fig. 88.1).

• More common in males than females, and incidence increases with age.

• In fair-skinned individuals, the risk factors for and the locations of invasive SCC are similar to those for AKs and SCC in situ (see above and Table 88.1).

• In all phototypes, invasive SCC may develop in sites of HPV infection, scars, chronic injury or inflammation, previous radiation therapy, or chemical exposure (e.g. polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; see Table 88.1).

• Common clinical presentation is an erythematous, keratotic papule or nodule that arises within a background of sun-damaged skin; tenderness common; often a history of rapid enlargement (Fig. 88.5) and sometimes a history of antecedent trauma.

Fig. 88.5 Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). A A large keratotic nodule on the supraorbital region in an elderly woman; note the coarse wrinkling and solar elastosis of the face. B Eroded and keratotic nodule that developed rapidly at the site of trauma on the shin. C Large, fungating nodule on the dorsum of the hand. D Multiple eroded superficial SCCs in association with hypertrophic AKs on the cheek and neck of an elderly man. E Erosive, slightly vegetating, thick plaque arising within lichen sclerosus of the vulva. F Firm, eroded red plaque on the scrotum; histopathologically, the SCC was moderately differentiated. A, C, D, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD; B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD. E, F, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD.

• Clinical variants: keratoacanthoma (KA) (Fig. 88.6), verrucous carcinoma (Fig. 88.7), mucosal (Fig. 88.8), periungual and subungual.

Fig. 88.6 Clinical spectrum of keratoacanthomas. A, B Rapidly growing, erythematous crateriform nodules with a rolled border and central keratotic core. C Progressive peripheral expansion and central involution with residual atrophy characterize keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum. D Giant keratoacanthoma with a yellow-red color and a history of rapid growth. A, D, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD.

Fig. 88.7 Verrucous carcinoma. A Long-standing large nodule on the plantar surface with a rabbit burrow-like appearance; such a tumor is also referred to as an epithelioma cuniculatum. B Keratotic and ulcerated plaque on the ventromedial aspect of the great toe. The lesion was originally misdiagnosed as a plantar wart. C A classic location in an amputation stump. In general, these well-differentiated SCCs enlarge slowly. A, C, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD.

Fig. 88.8 Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the lower lip. A Extensive hyperkeratosis and leukoplakia of the lower vermilion lip; histopathologically, the SCC was superficially invasive and well-differentiated. B Verrucous and eroded nodule on the lower vermilion lip in a heavy smoker. A, B, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD.

• DDx:

– Most common: AK, HAK, SCC in situ, BCC, verruca vulgaris, irritated SK.

– Less common: amelanotic melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), Merkel cell carcinoma, adnexal tumors, prurigo nodularis.

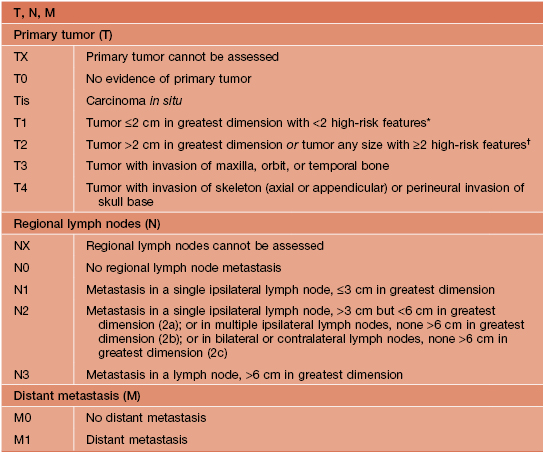

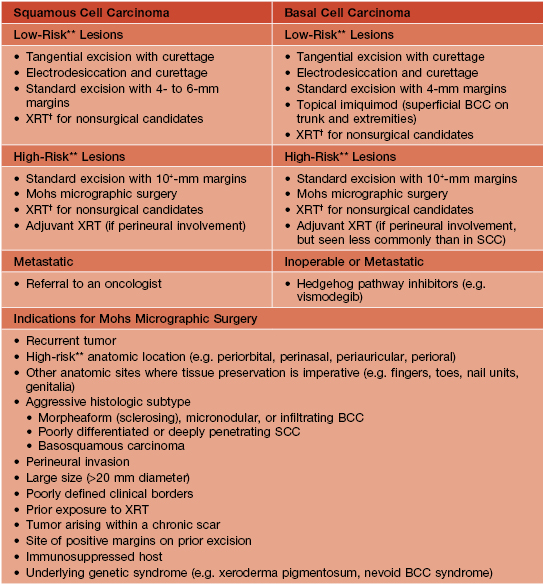

• A cutaneous SCC staging format has been proposed by the American Joint Commission on Cancer, incorporating the TNM criteria, prognostic factors (tumor thickness, ± perineural invasion, high-risk locations, ± lymph node involvement), histologic grade, and the presence or absence of lymphatic/vascular invasion on histology (Table 88.3).

Table 88.3

Staging of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

* High-risk features for the primary tumor (T) staging:

Depth/invasion: >2 mm thickness, Clark level ≥IV, perineural invasion.

Anatomic location: primary site ear, primary site hair-bearing lip.

† Excludes cutaneous SCC of the eyelid.

Adapted from American Joint Committee on Cancer, 2010.

• Long-term prognosis for adequately treated SCC is excellent.

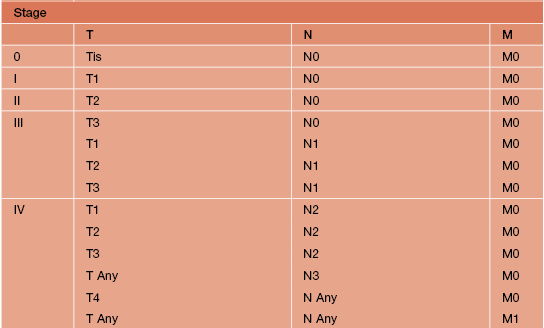

• There are several risk factors for nodal metastasis: lesions on the lip, ear, and genitalia; tumor diameter ≥2 cm; poorly differentiated histology; invasion beyond the subcutaneous fat; and perineural invasion (Table 88.4).

Table 88.4

Characteristics of high-risk* non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC)**

* High-risk of recurrence.

** Includes BCC and SCC.

Area L – low-risk anatomic sites: trunk, extremities.

Area M – middle-risk anatomic sites: cheeks, forehead, neck, scalp.

Area H – high-risk anatomic sites: ‘mask areas’ of face, genitalia, hands, feet.

BCC, basal cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; XRT, radiation therapy.

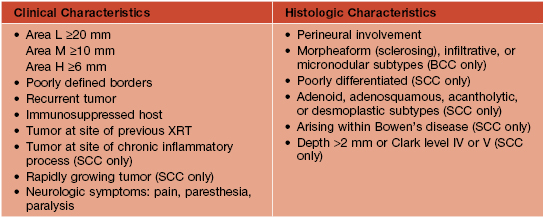

• Rx: primarily excision, but based on risk factors (see Table 88.4), ranges from electrodesiccation and curettage (e.g. smaller, minimally invasive lesion in an elderly patient) to Mohs micrographic surgery (Table 88.5).

Table 88.5

Common treatment options for non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC)*

* Includes BCC and SCC.

** High risk for recurrence; see characteristics of such lesions in Table 88.4.

† Excluding genitalia, hands, and feet.

BCC, basal cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; XRT, radiation therapy.

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)

• Most common NMSC in humans; arises de novo, with no known precursor lesion.

• UV exposure is the greatest risk factor, but in contrast to AK/SCC, intense episodes of burning are more important than chronic long-term exposure; in addition, BCCs can also arise in relatively non-sun-exposed areas, e.g. retroauricular crease and inner canthus (Fig. 88.9B).

Fig. 88.9 Clinical spectrum of nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). A Translucent papulonodule with prominent telangiectasias on the infraorbital cheek. B Classic presentation with a pearly rolled border and central hemorrhagic crust. C Larger plaque with rolled borders and multiple telangiectasias. D Nodulo-ulcerative tumor of the preauricular region with translucent rolled borders, most obvious at “noon.” E Dermoscopy of a nodular BCC with striking arborizing vessels. F Dermoscopy of a pigmented BCC demonstrating the classic arborizing telangiectasias and multiple blue-gray ovoid globules, pointing to the diagnosis of a small nodular BCC; the one large blue-brown structure resembles, but does not fulfill all the criteria for, a large gray-blue ovoid nest. A, Courtesy, Stanley J. Miller, MD; C, D, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD; E, F, Courtesy, Giuseppe Argenziano, MD.

• Multiple clinical variants and varied presentations.

– Most common: nodular (pearly papule with telangiectasias and/or umbilication; Fig. 88.9), superficial (typically an erythematous thin plaque on trunk > extremities; Fig. 88.10), pigmented (Fig. 88.11).

Fig. 88.10 Superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC). A Numerous erythematous patches and thin plaques on the back of a man with a history of arsenic exposure decades previously. B A solitary large, thin, dark pink plaque. There are scattered areas of fine scaling and small foci of brown pigment within the rolled border. As a rule, these lesions are neither pruritic nor tender. A, B, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD.

Fig. 88.11 Pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC). A In addition to the admixture of scale and hemorrhagic crusts centrally, there is a translucent and black rolled border superiorly. B The clinical differential diagnosis of this small nodular pigmented BCC includes nodular melanoma. However, the glassy translucency, in concert with characteristic dermoscopic features, will point to the diagnosis of pigmented BCC. A, B, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD.

– Less common: morpheaform (scar-like; Fig. 88.12), micronodular, cystic, basosquamous, and fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (Fig. 88.13).

Fig. 88.12 Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC). A Recurrent tumor 2 years after microscopically controlled surgery; note the scar-like appearance with superimposed glassy pink and brown papules. B A classic example with indistinct borders and a scar-like appearance. A, Courtesy, Darrell S. Rigel, MD; B, Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD.

Fig. 88.13 Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. This soft, skin-colored to light pink, broad, sessile nodule on the lower back representing a fibroepithelioma is adjacent to a classic nodular BCC. Courtesy, H. Peter Sawyer, MD.

• Dx: biopsy; dermoscopy can assist in diagnosis (see Fig. 88.9E,F).

• DDx: nodular: intradermal melanocytic nevus, fibrous papule, sebaceous hyperplasia, invasive SCC, amelanotic melanoma; superficial: LPLK, AK, SCC in situ, isolated lesion of psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis or nummular eczema, amelanotic melanoma; morpheaform: scar, adnexal tumors (e.g. desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma [see Chapter 91]); pigmented: melanocytic nevus, seborrheic keratosis, pigmented SCC in situ, nodular melanoma.

• Categorize tumor into histologic subtype and whether or not meets criteria for high-risk BCC (e.g. morpheaform, micronodular, or infiltrative; see Table 88.4) or indications for Mohs micrographic surgery to determine best treatment (see Table 88.5); basosquamous lesions are treated as invasive SCCs (see above).

• Nevoid BCC syndrome: rare, autosomal dominant, caused by mutations in human PTCH gene; characterized by multiple BCCs, palmoplantar pits, odontogenic keratocysts of jaw, skeletal abnormalities, macrocephaly, and calcification of the falx cerebri; patients may develop medulloblastomas during childhood or ovarian fibromas.

For further information see Ch. 108. From Dermatology, Third Edition.