72 Acquired Polyneuropathies

Diagnostic Approach

Clinical Vignette

The evaluation for the etiology of a patient’s polyneuropathy can be very challenging for many reasons, including the fact that there are more than 100 potential etiologies (Fig. 72-1). Ultimately the polyneuropathy is determined to be acquired (i.e., caused by some other disease or exposure) in one third of cases (Box 72-1), inherited in another one third of cases (see Chapter 71), and—in spite of appropriate testing—idiopathic in the remaining one third of cases. In order to focus on a smaller list of potential etiologies so that the evaluation can be simplified, we believe that it is best for the clinician to first characterize the polyneuropathy and the patient. We will present one method for characterizing neuropathy that is easy to remember, based on four simple clinical questions about the neuropathy and the patient: “What?” “Where?” “When?” and “What setting?”

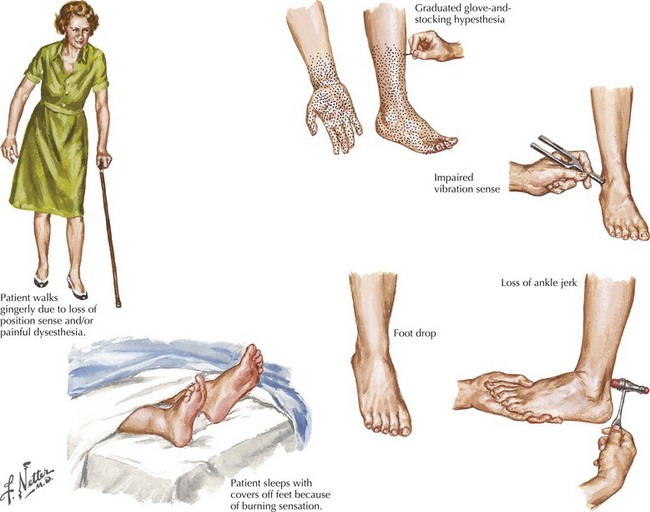

“What?” refers to what nerve fiber modalities (motor, sensory, autonomic, or a combination) are involved? The identification of sensory nerve involvement, at a minimum, allows the clinician to exclude other neuromuscular diseases not associated with sensory dysfunction, such as disorders of anterior horn cells (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), neuromuscular transmission (e.g., myasthenia gravis), or of muscle (myopathy). When sensory symptoms and signs are present, it is useful to characterize neuropathic sensory symptoms into “positive” or “negative” because acquired neuropathies are usually accompanied by positive neuropathic sensory symptoms and inherited neuropathies are usually not. Positive sensory symptoms may be painful (e.g., “burning,” “freezing,” or “throbbing”) or painless (e.g., “tingling” or “swelling”) (Box 72-2). Paresthesias and pain (positive neuropathic sensory symptoms) are common complaints for patients with diabetic, vasculitic, alcoholic, or uremic neuropathy and patients with Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP). In the clinical vignette presented above, the patient had prominent positive neuropathic sensory symptoms, strongly suggesting that the etiology of her neuropathy is acquired rather than inherited. Patients with neuropathy often also complain of exaggerated discomfort to painful sensory stimuli (hyperalgesia) and to nonpainful sensory stimuli (allodynia). Patient complaints indicative of negative neuropathic sensory symptoms include loss of sensation and imbalance (i.e., sensory ataxia). Most patients with neuropathy have some degree of motor nerve involvement that at times is overshadowed by the sensory complaints. Our patient had prominent motor nerve fiber involvement.

Box 72-2 Painful Polyneuropathies*

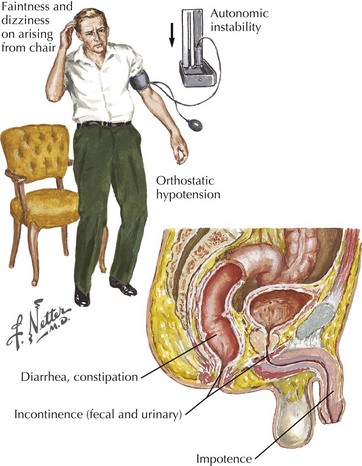

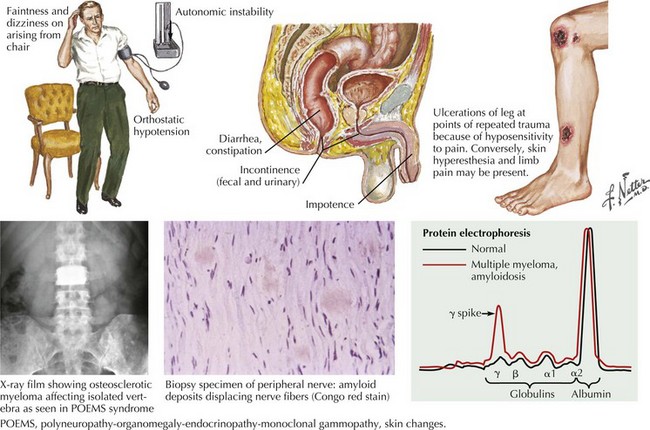

Identification of autonomic nerve involvement can be an important clue because only a small number of neuropathic processes affect both autonomic and somatic nerves (e.g., GBS, paraneoplastic neuropathy, diabetic neuropathy, amyloid neuropathy) (Box 72-3). Autonomic symptoms include lightheadedness, syncope, diarrhea, constipation, postprandial bloating, early satiety, urinary complaints, erectile dysfunction, abnormal or absent sweating, and dry mouth and eyes (Fig. 72-2). Our patient did not have discernible autonomic nervous system involvement.

Box 72-3 Polyneuropathies with Autonomic Nervous System Involvement

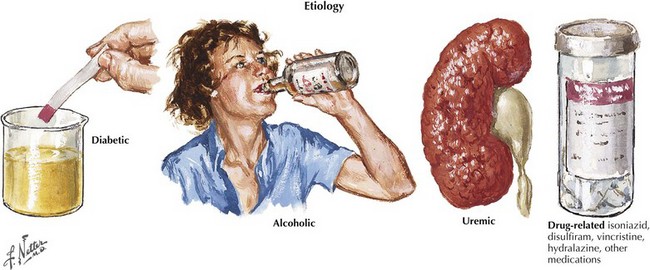

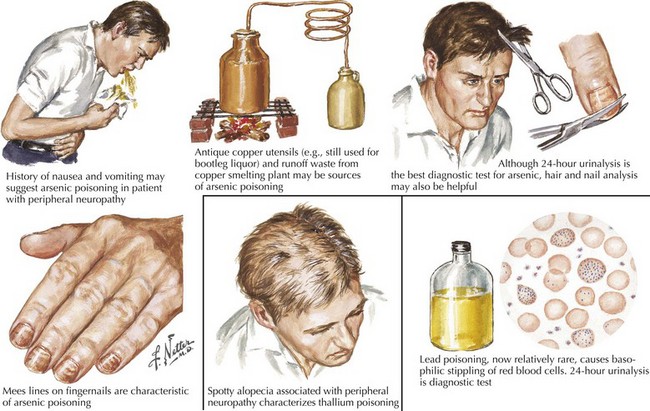

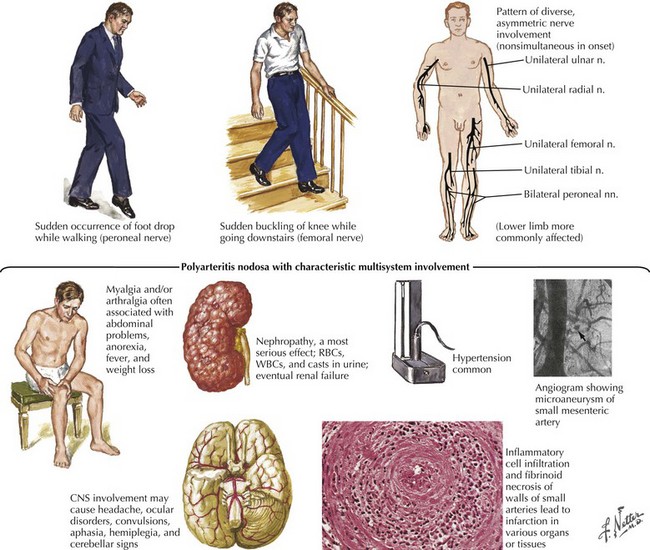

“What setting?” refers to an elaboration of the unique clinical circumstance of the individual patient. This is done by determining what in the patient’s past medical history, medication list, social history, family history, and the review of systems may be relevant (Fig. 72-3). An understanding of the significance of these clinical factors requires knowledge of the risk factors of neuropathy and knowledge of the clinical features of the diseases that may be risk factors for neuropathy. For example, unexplained weight loss raises concern for vasculitis or malignancy (e.g., small cell lung cancer), both of which cause an immune-mediated neuropathy. The neuropathy secondary to malignancy (e.g., paraneoplastic neuropathy) usually presents differently than vasculitic neuropathy, so it is usually not too difficult to differentiate these two etiologies. A clinical setting of known diabetes mellitus or known kidney disease would elevate those comorbidities on the differential diagnosis. Heavy metal poisoning or other intoxication, although rare, needs to be considered in the patient with systemic symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting) and other manifestations suspicious for poisoning (Fig. 72-4). Our patient’s presentation is of vasculitic neuropathy rather than paraneoplastic neuropathy.

The fifth step in characterization requires NCS and EMG. NCS and EMG can contribute to (or rarely refute) the clinical characterization in terms of “what” and “where,” as well as provide another view of the temporal evolution (“when”). NCS and EMG can also characterize the neuropathy as being primarily axonal or demyelinating. Neuropathies with axonal injury are far more common than those primarily with demyelination, but the identification of a primarily demyelinating polyneuropathy is very important because acquired demyelinating polyneuropathies (e.g., GBS, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, multifocal motor neuropathy) are generally treatable. They are usually immune-mediated and treatable with immunotherapy (e.g., corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin [IVIG], plasmapheresis) (Box 72-4). NCS and EMG can also assess for subclinical involvement and provide baseline parameters in case future testing is necessary to monitor the patient’s course. Our patient’s NCS and EMG confirmed multiple, axonal mononeuropathies. It is important to note that the localization of each mononeuropathy was not at common sites of nerve entrapment, such as the elbow for the ulnar nerve and the fibular head for the peroneal nerve; thus, a compression or entrapment mechanism of injury is not plausible (given the other facts of the case, it would have been very unlikely anyway).

Vasculitis is only one of the more than 100 different causes of neuropathy (Fig. 72-5). It is a far less common cause of acquired neuropathy than diabetic, alcoholic, or uremic neuropathy, but it is very important to diagnose—and to do so quickly—because undiagnosed and untreated systemic vasculitis may be fatal. See discussion on vasculitic neuropathies below.

Idiopathic Length-Dependent Polyneuropathies

Polyneuropathies are one of the most common neurologic disorders; the length-dependent pattern is the most prevalent. Although there are many recognized causes of polyneuropathy, specific mechanisms have not been identified in 30–40% of patients, and these patients are deemed to have idiopathic neuropathy (Box 72-5).

Box 72-5 Length-Dependent Polyneuropathies

Dysimmune/Inflammatory

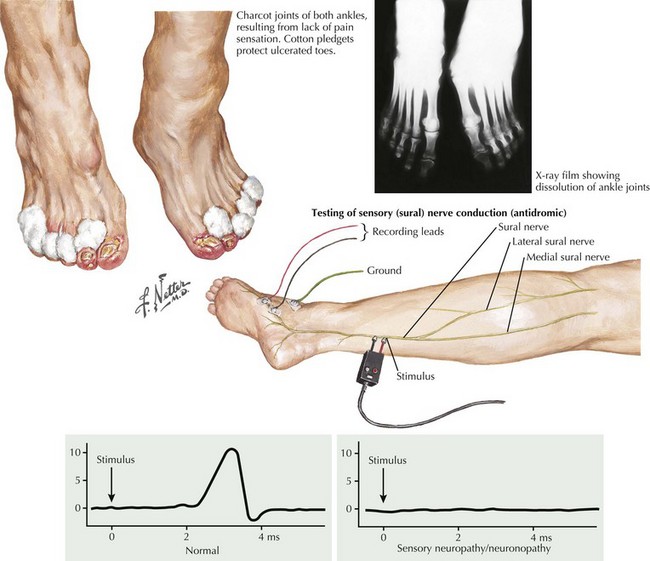

Pure sensory neuropathies fit into the LDPN pattern such as with diabetes mellitus, renal disease, vitamin deficiencies, various toxins, Sjögren syndrome, and amyloidosis (Fig. 72-6), or represent a primary sensory ganglionopathy. The latter may be clinically suspected by its initially proximal, non–length-dependent pattern of involvement. EMG can aid confirmation.

Identifying the LDPN per se is usually the easiest part of the evaluation. Determination of etiologic mechanism requires careful consideration and thorough investigation, although this does not always yield precisely identifiable mechanisms. For example, not all neuropathies in patients with diabetes mellitus are related to that disorder. Other mechanisms may be responsible and must be sought. After determining that a neuropathy best fits an LDPN pattern, the clinician must search for additional clues to the differential diagnosis. Evaluation of a patient’s risk factor profile from personal and family history, toxic exposures, and other symptoms such as pain, dysautonomia, or indications of a systemic disorder is important. A careful evaluation leads to specific diagnosis in about 50% of patients. Diagnosis is often made on an associative basis without absolute proof of causation. Treatable neuropathies are more common among disorders presenting acutely or subacutely. Toxic or metabolic etiologies (see Fig. 72-3) are common causes of sensory LDPN, whereas genetic mechanisms underlie most motor-predominant distal polyneuropathies.

Many potential peripheral neurotoxins exist, including alcohol and therapeutic drugs. In some pharmaceuticals, neurotoxicity limits the dose. Neuropathies resulting from cryptic sources such as heavy metals are uncommon or uncommonly recognized (see Fig. 72-4). However, in certain parts of North America arsenic poisoning is still seen. The role of nutritional and vitamin deficiency versus that of ethanol in the development of “alcoholic” neuropathy is uncertain.

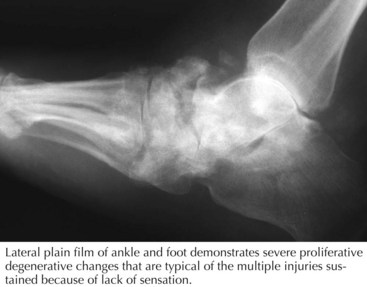

Neuropathies Associated With Diabetes

The sensory predominant LDPN associated with diabetes is the most common type of neuropathy seen. Sensory loss begins in the tips of the toes and gradually progresses to involve the fingers. This may be associated with degeneration of small nerve fibers and can be very painful. Additionally the LDPN of the patient with diabetes may coexist with a diabetic vasculopathy. This combination can result in nonhealing ulcers and rarely gangrene of the toes requiring surgery such as amputations (Fig. 72-7). Motor strength is usually preserved and electrodiagnostic studies will reveal a length-dependent sensory predominant axonal process. Treatment of this condition consists of improved control of diabetes and symptomatic treatment of neuropathic pain. Medications such as gabapentin, pregabalin, and tricyclic antidepressants are used for neuropathic pain.

Guillain–Barré Syndrome

Clinical Vignette

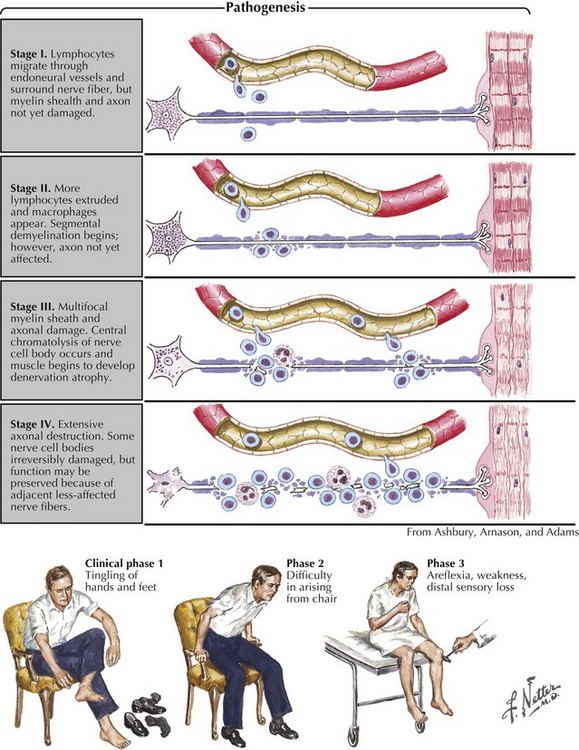

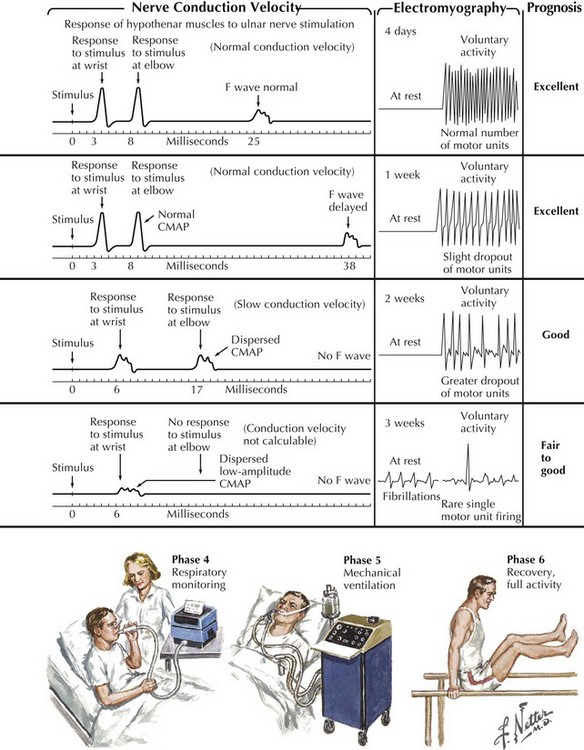

Guillain–Barré syndrome is a classic acute autoimmune polyneuropathy (Fig. 72-8). Characteristically, it presents in a previously healthy person with the rapid onset of symmetric weakness, areflexia, and generally minimal sensory symptoms with the exception of severe pain in some individuals. Typical CSF findings are an albuminocytologic dissociation with increased protein and fewer than 5–10 WBCs. Additional findings include gait ataxia and cranial and autonomic nerve involvement. Although GBS is the most common cause of acute flaccid paralysis, a primary spinal cord lesion and rarely a poliomyelitis-like illness such as seen now with the West Nile virus, must always be considered early in the clinical course.

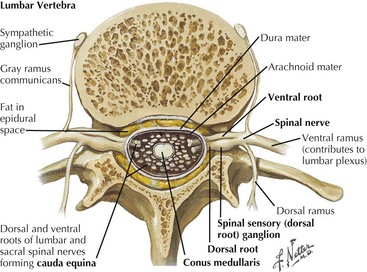

GBS, sometimes known as acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP), and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP) are common acquired polyradiculopathies. Both are autoimmune processes that share the unusual feature of significant widespread peripheral—often including nerve root (Fig. 72-9) and sometimes cranial nerve—involvement. Consequently, these disorders are categorized as polyradiculoneuropathies rather than polyneuropathies.

The major clinical difference between GBS and CIDP is the temporal course. GBS is a monophasic illness of acute onset that usually reaches a nadir within 1–4 weeks and then gradually improves (see Fig. 72-8). CIDP has a slower onset and more prolonged course that is progressive, monophasic, or relapsing. Most cases of childhood or adult CIDP present within 6 months of symptom onset. Sometimes CIDP can present acutely, mimicking GBS, to be diagnosed correctly only later when a clinical relapse occurs.

The immune attack in GBS and CIDP is widespread and occurs proximally at the nerve roots and distally at the motor axon terminal. These two sites are theoretically more vulnerable because of their less complete blood–nerve barriers. Both cellular and humoral immune mechanisms seem to be involved. Lymphocytes and macrophages are the effector cells involved in damaging myelin and the adjacent axons (see Fig. 72-8). Motor, sensory, and autonomic nerves are affected. The weakness and sensory disturbances are due to nerve fiber action potential conduction block (secondary to demyelination) or conduction failure (due to axon damage).

Differential Diagnosis Of Demyelinating Polyneuropathies

In tick paralysis, an unidentified tick saliva toxin most likely interacts with nerve ion channels, producing an acute paralytic illness mimicking GBS. This is most common in girls and young women, in whom ticks can become hidden in their scalp hair. Examiners must always search for ticks in any patient with an acute flaccid paralysis. These are relatively large sized when engorged and easily recognized (Fig. 72-10) when one carefully examines the scalp. In North America, the recovery is rapid and complete after the tick is dislodged.

Botulism and myasthenia gravis may produce an acute generalized weakness. Botulism is typically acute in onset and myasthenia is usually more indolent, although myasthenia gravis can have a relatively rapid presentation with cranial nerve and peripheral distribution weakness. Neither produces sensory system involvement. Both have a predilection for oculobulbar musculature. Botulism may also have prominent manifestations of cholinergic dysautonomia. EMG may be required for distinction from GBS. Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) may mimic CIDP with a subacute onset of proximal weakness and areflexia. History of tobacco addiction and a dry mouth suggest LEMS (Chapter 74).

AIDP and CIDP Variants

Although the confirmation of GBS or CIDP primarily rests on clinical features, CSF analysis, EMG (see Fig. 72-8), serum immunophoresis, and treatment response provide the best means to make a precise diagnosis. An increased level of CSF protein (>50 mg/dL) without pleocytosis (<10 cells/mm3) is common in GBS and CIDP. CSF examination is often normal within the first week of GBS; however, approximately 90% of patients with CIDP and patients with late GBS have an increased level of CSF protein. Although 10–50 cells/mm3 in the CSF may occur in GBS, more than 50 cells/mm3 must arouse suspicion of an alternate diagnosis, including Lyme neuroborreliosis, HIV-associated polyradiculoneuropathy, poliomyelitis, or lymphomatous meningoradiculitis.

Sensory Neuronopathies

Clinical Vignette

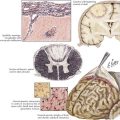

Most patients with peripheral neuropathies present with slowly ingravescent sensory symptoms and signs typical of a length-dependent polyneuropathy (LDPN). Another, smaller population of sensory-impaired individuals has pathophysiology primarily affecting the sensory neuron cells within the dorsal root ganglion (in contrast to neuropathies, affecting the distal nerve axon) (Fig. 72-11). They are described as having a primary sensory neuronopathy. The acute onset is often typified by a painful, noxious clinical picture with a generalized distribution. The dorsal root ganglia (DRG) sensory peripheral nerve cell bodies are the primary target of the disease process in patients with sensory neuronopathies. This anatomic locale explains why these disorders present with a non–length-dependent clinical pattern. Disproportionate loss of position and other discriminatory modalities occur when large sensory fibers are affected. Severe sensory ataxia frequently presents. Distinguishing between sensory LDPN and sensory neuronopathy is important because their differential diagnoses vary considerably. Often, a clinically suspected diagnosis can be confirmed with EMG.

EMG is the initial study because it provides a means to differentiate between LDPN and sensory neuronopathy. Almost all patients with LDPNs, even those without clinical weakness, have EMG evidence of motor involvement. These are recognized by motor nerve conduction study changes, needle electrode examination abnormalities, or both (Fig. 72-12). Patients with a primary DRG lesion, that is, sensory neuronopathy, have only sensory nerve conduction study abnormalities.

When sensory neuronopathies are confirmed, subsequent ancillary testing is limited to disorders known to cause such patterns (Box 72-6). The various causes of sensory LDPN may also require consideration (Box 72-7). Testing for serum anti-Hu antibodies is indicated in sensory neuronopathy evaluation, particularly for patients with a smoking or asbestos-exposure history. They are sensitive and specific for paraneoplastic neurologic disorders, particularly those with occult malignancies such as small cell lung cancer. Chest CT is indicated because the neuropathy may precede malignancy recognition by several years. Patients with suspected Sjögren syndrome require serologic tests, particularly SSA and SSB antibodies. Other potentially beneficial studies include the Schirmer test of lacrimation and slit lamp examination of the conjunctiva after Rose-Bengal staining. Minor salivary gland (usually lip) biopsy is performed if the diagnosis remains unconfirmed with less invasive means. Vitamin B12 levels and a serologic test for syphilis are important for evaluation of patients with large-fiber sensory dysfunction. When the vitamin B12 level is borderline, the more sensitive blood or urine tests for homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, or both are helpful. A nerve biopsy is usually not indicated in sensory neuronopathies.

2009 AAN practice parameter: Practice Parameter: Evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: Role of autonomic testing, nerve biopsy, and skin biopsy (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2009;72:1.

Barohn RJ. Approach to peripheral neuropathy and neuronopathy. Semin Neurol. 1998;18:7-18.

Burns TM. Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Seminars in Neurology. 2008;28:152-167.

Dispenzieri A. POEMS syndrome. Blood Reviews. 2007;21:285-299.

Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, Lacy MQ, Rajkumar SV, Therneau TM, Larson DR, Greipp PR, Witzig TE, Basu R, Suarez GA, Fonseca R, Lust JA, Gertz MA. POEMS syndrome: definitions and long-term outcome. Blood. 2003;101:2496-2506.

Dyck PJ, Dyck PJ, Grant IA, Fealy RD. Ten steps in characterizing and diagnosing patients with peripheral neuropathy. Neurology. 47(10-17), 1996.

England JD, Asbury AK. Peripheral neuropathy. Lancet. 2004;363:2151-2161.

Mauermann ML, Burns TM. The evaluation of chronic axonal neuropathies. Seminars in Neurology. 2008;28:133-151.

Pourmand R. Evaluating patients with suspected peripheral neuropathy: do the right thing, not everything. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:288-290.

Sabin TD. Classification of peripheral neuropathy: The long and the short of it. Muscle and Nerve. 1986;9:711-719.

Saperstein DS. Chronic acquired demyelinating polyneuropathies. Seminars in Neurology. 2008;28:168-184.

Saperstein DS, Wolfe GI, Granseth GS, et al. Challenges in the identification of cobalamin-deficiency polyneuropathy. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1296-1301.