Chapter 6 Acquired Disorders of Red Cell, White Cell, and Platelet Production

Table 6-2 Classification of Neutropenia

| Congenital | |

| Primary | Autoimmune neutropenia |

| Pure white cell aplasia | |

| Idiopathic | |

| Thymoma | |

| Hematologic malignancies (e.g., T-LGL leukemia) | |

| Infections/postinfectious | |

| Viral | |

| Measles,53 mumps, roseola,54,55 rubella,56 RSV, influenza57 | |

| Hepatitis A,58 B,58,59 and C60 | |

| CMV,61–63 EBV,64–66 HIV67,68 | |

| Parvovirus69–71 | |

| Bacterial | |

| Tuberculosis72,73 | |

| Brucellosis74–76 | |

| Tularemia77 | |

| Typhoid fever78 | |

| Rickettsial | |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever79 | |

| Ehrlichiosis80,81 | |

| Fungal | |

| Histoplasmosis82,83 | |

| Parasitic | |

| Malaria,84 leishmaniasis85,86 | |

| Autoimmune conditions (e.g., SLE87,88, RA89) | |

| Drugs and chemicals | |

| Neutropenia associated with immunodeficiency90,91 | |

| Severe nutritional deficiencies92,93 | |

| Neutropenia due to increased margination | |

| Iatrogenic (e.g., hemodialysis94,95) |

CMV, Cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; RA, refractory anemia; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; T-LGL, T-cell large granular lymphocyte.

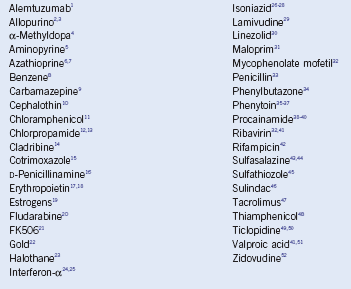

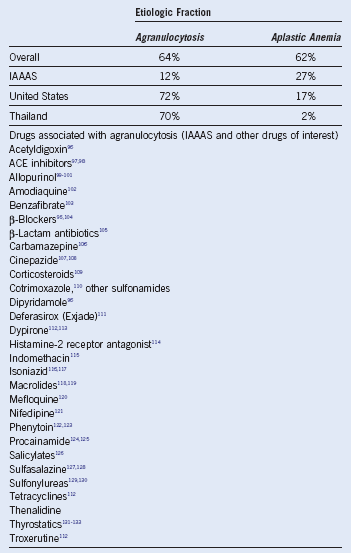

Table 6-3 Drugs Associated With Agranulocytosis

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; IAAAS, International Agranulocytosis and Aplastic Anemia Study.

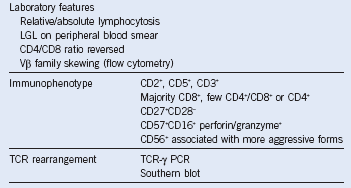

Table 6-4 Immunophenotype and Laboratory Features of T-Cell Large Granular Lymphocyte Leukemia

LGL, Large granular lymphocyte; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TCR, T-cell receptor.

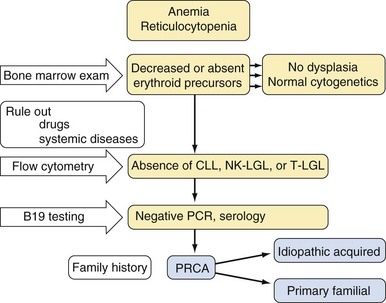

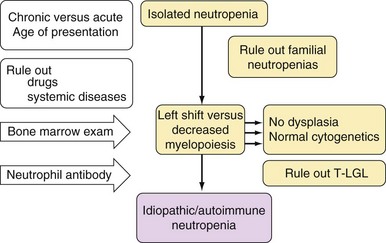

Approach to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acquired Pure Red Cell Aplasia, Acquired Neutropenia, and T-Cell Large Granular Lymphocyte Leukemia

1 Thachil J, Salim R. Campath-1H induced pure red cell aplasia in a patient with chronic lymphatic leukaemia. Leuk Res. 2006;31:1025.

2 Shankar P, Aish L, Hassoun H. Allopurinol-induced pure red cell aplasia. Am J Hematol. 2003;73:69.

3 Lin YW, Okazaki S, Hamahata K, et al. Acute pure red cell aplasia associated with allopurinol therapy. Am J Hematol. 1999;61:209.

4 Itoh K, Wong P, Asai T, et al. Pure red cell aplasia induced by alphamethyldopa. Am J Med. 1988;84:1088.

5 Blanchet E, Beau P, Frat JP. [Bone marrow aplasia following dipyrone treatment in a patient with Crohn’s disease receiving long-term methotrexate]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:502.

6 Agrawal A, Parrott NR, Riad HN, et al. Azathioprine-induced pure red cell aplasia: Case report and review. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:2689.

7 Pruijt JF, Haanen JB, Hollander AA, et al. Azathioprine-induced pure red-cell aplasia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:1371.

8 Lima CS, Paula EV, Takahashi T, et al. Causes of incidental neutropenia in adulthood. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:705.

9 Chandra Sekhar C, Ramana Reddi V, Srinivas B, et al. Pure red cell aplasia associated with carbamazepine. J Assoc Physicians India. 1998;46:655.

10 MacCulloch D, Jackson JM, Venerys J. Letter: Drug-induced red cell aplasia. Br Med J. 1974;4:163.

11 Fernandez de Sevilla T, Alegre J, Vallespi T, et al. Adult pure red cell aplasia following topical ocular chloramphenicol. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74:640.

12 Gill MJ, Ratliff DA, Harding LK. Hypoglycemic coma, jaundice, and pure RBC aplasia following chlorpropamide therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:714.

13 Planas AT, Kranwinkel RN, Soletsky HB, et al. Chlorpropamideinduced pure RBC aplasia. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:707.

14 Chasty RC, Myint H, Oscier DG, et al. Autoimmune haemolysis in patients with B-CLL treated with chlorodeoxyadenosine (CDA). Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;29:391.

15 Unter CE, Abbott GD. Co-trimoxazole red cell aplasia in leukaemia. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:85.

16 Tishler M, Kahn Y, Yaron M. Pure red cell aplasia caused by D-penicillamine treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50:255.

17 Jacob A, Sandhu K, Nicholas J, et al. Antibody-mediated pure red cell aplasia in a dialysis patient receiving darbepoetin alfa as the sole erythropoietic agent. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2963.

18 Shinohara K. Pure red cell aplasia caused by antibody to erythropoietin successfully treated by cyclosporine administration. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:247.

19 Boorman GA, Luster MI, Dean JH, et al. Assessment of myelotoxicity caused by environmental chemicals. Environ Health Perspect. 1982;43:129.

20 Borthakur G, O’Brien S, Wierda WG, et al. Immune anaemias in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab—incidence and predictors. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:800.

21 Suzuki S, Osaka Y, Nakai I, et al. Pure red cell aplasia induced by FK506. Transplantation. 1996;61:831.

22 Hansen RM, Varma RR, Hanson GA. Gold induced hepatitis and pure red cell aplasia. Complete recovery after corticosteroid and Nacetylcysteine therapy. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1251.

23 Jurgensen JC, Abraham JP, Hardy WW. Erythroid aplasia after halothane hepatitis. Report of a case. Am J Dig Dis. 1970;15:577.

24 Sacchi S, Gugliotta L, Papineschi F, et al. Alfa-interferon in the treatment of essential thrombocythemia: Clinical results and evaluation of its biological effects on the hematopoietic neoplastic clone. Italian Cooperative Group on ET. Leukemia. 1998;12:289.

25 Mazur EM, Rosmarin AG, Sohl PA, et al. Analysis of the mechanism of anagrelide-induced thrombocytopenia in humans. Blood. 1992;79:1931.

26 Marseglia GL, Locatelli F. Isoniazid-induced pure red cell aplasia in two siblings. J Pediatr. 1998;132:898.

27 Veale KS, Huff ES, Nelson BK, et al. Pure red cell aplasia and hepatitis in a child receiving isoniazid therapy. J Pediatr. 1992;120:146.

28 Hoffman R, McPhedran P, Benz EJ, Jr., et al. Isoniazid-induced pure red cell aplasia. Am J Med Sci. 1983;286:2.

29 Majluf-Cruz A, Luna-Castanos G, Trevino-Perez S, et al. Lamivudineinduced pure red cell aplasia. Am J Hematol. 2000;65:189.

30 Monson T, Schichman SA, Zent CS. Linezolid-induced pure red blood cell aplasia. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:E29.

31 Nicholls MD, Concannon AJ. Maloprim-induced agranulocytosis and red-cell aplasia. Med J Aust. 1982;2:564.

32 Hodo Y, Tsuji K, Mizukoshi E, et al. Pure red cell aplasia associated with concomitant use of mycophenolate mofetil and ribavirin in posttransplant recurrent hepatitis C. Transpl Int. 2006;19:170.

33 Cavanzo FJ, Garcia CF, Botero RC. Chronic cholestasis, paucity of bile ducts, red cell aplasia, and the Stevens-Johnson syndrome. An ampicillin-associated case. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:854.

34 Giorgino R. [Hemorrhagic syndrome with medullary aplasia of notable gravity during mixed therapy with phenylbutazone and Pyramidon]. Progr Med (Napoli). 1963;19:316.

35 Dessypris EN, Redline S, Harris JW, et al. Diphenylhydantoin-induced pure red cell aplasia. Blood. 1985;65:789.

36 Kueh YK, Yeo TC, Choo MH. Reversible pure red cell aplasia associated with diphenylhydantoin therapy. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1991;20:407.

37 Huijgens PC, Thijs LG, den Ottolander GJ. Pure red cell aplasia, toxic dermatitis and lymphadenopathy in a patient taking diphenylhydantoin. Acta Haematol. 1978;59:31.

38 Pasha SF, Pruthi RK. Procainamide-induced pure red cell aplasia. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:125.

39 Agudelo CA, Wise CM, Lyles MF. Pure red cell aplasia in procainamide induced systemic lupus erythematosus. Report and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1431.

40 Giannone L, Kugler JW, Krantz SB. Pure red cell aplasia associated with administration of sustained-release procainamide. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1179.

41 MacDougall LG. Pure red cell aplasia associated with sodium valproate therapy. JAMA. 1982;247:53.

42 Mariette X, Mitjavila MT, Moulinie JP, et al. Rifampicin-induced pure red cell aplasia. Am J Med. 1989;87:459.

43 Anttila PM, Valimaki M, Pentikainen PJ. Pure-red-cell aplasia associated with sulphasalazine but not 5-aminosalicylic acid. Lancet. 1985;2:1006.

44 Dunn AM, Kerr GD. Pure red cell aplasia associated with sulphasalazine. Lancet. 1981;2:1288.

45 Strauss AM. Erythrocyte hypoplasia following sulfathiazole. Am J Clin Path. 1943;13:249.

46 Sanz MA, Martinez JA, Gomis F, et al. Sulindac-induced bone marrow toxicity. Lancet. 1980;2:802.

47 Misra S, Moore TB, Ament ME, et al. Red cell aplasia in children on tacrolimus after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;65:575.

48 De Renzo A, Formisano S, Rotoli B. Bone marrow aplasia and thiamphenicol. Haematologica. 1981;66:98.

49 Yamamoto N, Shiraki K, Saitou Y, et al. Ticlopidine induced acute cholestatic hepatitis complicated with pure red cell aplasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:84.

50 Ertorer ME, Gokcel A, Savas L, et al. Ticlopidine-induced marrow aplasia treated with cyclosporine. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2002;8:183.

51 Watts RG, Emanuel PD, Zuckerman KS, et al. Valproic acid-induced cytopenias: Evidence for a dose-related suppression of hematopoiesis. J Pediatr. 1990;117:495.

52 Weinkove R, Rangarajan S, van der WJ, et al. Zidovudine-induced pure red cell aplasia presenting after 4 years of therapy. AIDS. 2005;19:2046.

53 Arakawa Y, Matsui A, Sasaki N, et al. Agranulocytosis and thrombocytopenic purpura following measles infection in a living-related orthotopic liver transplantation recipient. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997;39:226.

54 Hashimoto H, Maruyama H, Fujimoto K, et al. Hematologic findings associated with thrombocytopenia during the acute phase of exanthema subitum confirmed by primary human herpesvirus-6 infection. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:211.

55 Takikawa T, Hayashibara H, Harada Y, et al. Liver dysfunction, anaemia, and granulocytopenia after exanthema subitum. Lancet. 1992;340:1288.

56 Hillenbrand FK. The blood picture in rubella; its place in diagnosis. Lancet. 1956;271:66.

57 Lewis DE, Gilbert BE, Knight V. Influenza virus infection induces functional alterations in peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1986;137:3777.

58 Amarapurkar DN, Amarapurkar AD. Extrahepatic manifestations of viral hepatitis. Ann Hepatol. 2002;1:192.

59 Iwamoto J, Hakozaki Y, Sakuta H, et al. A case of agranulocytosis associated with severe acute hepatitis B. Hepatol Res. 2001;21:181.

60 Ramos-Casals M, Garcia-Carrasco M, Lopez-Medrano F, et al. Severe autoimmune cytopenias in treatment-naive hepatitis C virus infection: Clinical description of 35 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:87.

61 Ivarsson SA, Ljung R. Neutropenia and congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7:436.

62 Avanzini A, Colombo T, Santucci S. Neutropenia in a cytomegalovirus (CMV) infected VVLBW infant. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:738.

63 Almeida-Porada GD, Ascensao JL. Cytomegalovirus as a cause of pancytopenia. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;21:217.

64 Savard M, Gosselin J. Epstein-Barr virus immunosuppression of innate immunity mediated by phagocytes. Virus Res. 2006;119:134.

65 Imashuku S, Tabata Y, Teramura T, et al. Treatment strategies for Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (EBV-HLH). Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;39:37.

66 Corcione A, Roncella S, Cutrona G, et al. Transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-beta 1) released by an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positive spontaneous lymphoblastoid cell line from a patient with Kostmann’s congenital neutropenia inhibits the growth of normal committed haemopoietic progenitors in vitro. Br J Haematol. 1993;85:684.

67 Zon LI, Groopman JE. Hematologic manifestations of the human immune deficiency virus (HIV). Semin Hematol. 1988;25:208.

68 Mulder AB, de Wolf JT, Smit JW, et al. Correction of neutropenia by GM-CSF in patients with a large granular lymphocyte proliferation. Ann Hematol. 1992;65:91.

69 McClain K, Estrov Z, Chen H, et al. Chronic neutropenia of childhood: Frequent association with parvovirus infection and correlations with bone marrow culture studies. Br J Haematol. 1993;85:57.

70 Koch WC, Massey G, Russell CE, et al. Manifestations and treatment of human parvovirus B19 infection in immunocompromised patients. J Pediatr. 1990;116:355.

71 Doran HM, Teall AJ. Neutropenia accompanying erythroid aplasia in human parvovirus infection. Br J Haematol. 1988;69:287.

72 Bozoky G, Ruby E, Goher I, et al. [Hematologic abnormalities in pulmonary tuberculosis]. Orv Hetil. 1997;138:1053.

73 Maartens G, Willcox PA, Benatar SR. Miliary tuberculosis: Rapid diagnosis, hematologic abnormalities, and outcome in 109 treated adults. Am J Med. 1990;89:291.

74 al Eissa Y, al Nasser M. Haematological manifestations of childhood brucellosis. Infection. 1993;21:23.

75 Crosby E, Llosa L, Miro QM, et al. Hematologic changes in brucellosis. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:419.

76 Galanakis E, Bourantas KL, Leveidiotou S, et al. Childhood brucellosis in north-western Greece: A retrospective analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155:1.

77 Syrjala H. Peripheral blood leukocyte counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in tularemia caused by the type B strain of Francisella tularensis. Infection. 1986;14:51.

78 Abdool Gaffar MS, Seedat YK, Coovadia YM, et al. The white cell count in typhoid fever. Trop Geogr Med. 1992;44:23.

79 Rose HM. The clinical manifestations and laboratory diagnosis of rickettsialpox. Ann Intern Med. 1949;31:871. illust

80 Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Horowitz HW, Wormser GP, et al. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis: A case series from a medical center in New York State. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:904.

81 Bakken JS, Krueth J, Wilson-Nordskog C, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. JAMA. 1996;275:199.

82 Davis KA, Finger DR, Shparago NI. Disseminated histoplasmosis mimicking Felty’s syndrome. J Clin Rheumatol. 2002;8:38.

83 Zuger A. Profound neutropenia in an HIV-infected man. AIDS Clin Care. 1996;8:67.

84 Dale DC, Wolff SM. Studies of the neutropenia of acute malaria. Blood. 1973;41:197.

85 Solano C, Gomez-Reino F, Fernandez-Ranada JM. Pure red cell aplasia in kala-azar. Acta Haematol. 1984;72:205.

86 Thomssen C, Nissen C, Gratwohl A, et al. Agranulocytosis associated with T-gamma-lymphocytosis: No improvement of peripheral blood granulocyte count with human-recombinant granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Br J Haematol. 1989;71:157.

87 Martinez-Banos D, Crispin JC, Lazo-Langner A, et al. Moderate and severe neutropenia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:994.

88 Hellmich B, Schnabel A, Gross WL. Treatment of severe neutropenia due to Felty’s syndrome or systemic lupus erythematosus with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1999;29:82.

89 Hellmich B, Pinals RS, Loughran TP, Jr., et al. New clues to accrue on neutropenia in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Immunol. 2005;117:1.

90 Winkelstein JA, Marino MC, Lederman HM, et al. X-linked agammaglobulinemia: Report on a United States registry of 201 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85:193.

91 Cham B, Bonilla MA, Winkelstein J. Neutropenia associated with primary immunodeficiency syndromes. Semin Hematol. 2002;39:107.

92 Becton DL, Schultz WH, Kinney TR. Severe neutropenia caused by copper deficiency in a child receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Pediatr. 1986;108:735.

93 Zidar BL, Shadduck RK, Zeigler Z, et al. Observations on the anemia and neutropenia of human copper deficiency. Am J Hematol. 1977;3:177.

94 Stroncek DF, Keshaviah P, Craddock PR, et al. Effect of dialyzer reuse on complement activation and neutropenia in hemodialysis. J Lab Clin Med. 1984;104:304.

95 Skubitz KM, Craddock PR. Reversal of hemodialysis granulocytopenia and pulmonary leukostasis: A clinical manifestation of selective downregulation of granulocyte responses to C5adesarg. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:1383.

96 Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Shapiro S. Risks of agranulocytosis and aplastic anemia in relation to the use of cardiovascular drugs: The International Agranulocytosis and Aplastic Anemia Study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991;49:330.

97 Horowitz N, Molnar M, Levy Y, et al. Ramipril-induced agranulocytosis confirmed by a lymphocyte cytotoxicity test. Am J Med Sci. 2005;329:52.

98 Jacquot C, Caudwell V, Belenfant X. Granulocytopenia after combined therapy with interferon and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: Evidence for a synergistic hematologic toxicity. Am J Med. 1996;101:235.

99 Lee EJ, Kueh YK. Allopurinol—induced skin reactions and agranulocytosis. Singapore Med J. 1982;23:178.

100 Scobie IN, MacCuish AC, Kesson CM, et al. Neutropenia during allopurinol treatment in total therapeutic starvation. Br Med J. 1980;280:1163.

101 Wilkinson DG. Allopurinol and agranulocytosis. Lancet. 1977;2:1282.

102 Hatton CS, Peto TE, Bunch C, et al. Frequency of severe neutropenia associated with amodiaquine prophylaxis against malaria. Lancet. 1986;1:411.

103 Ariad S, Hechtlinger V. Bezafibrate-induced neutropenia. Eur J Haematol. 1993;50:179.

104 Nawabi IU, Ritz ND. Agranulocytosis due to propranolol. JAMA. 1973;223:1376.

105 Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Jurgelon JM, et al. Drugs in the aetiology of agranulocytosis and aplastic anaemia. Eur J Haematol Suppl. 1996;60:23.

106 Blackburn SC, Oliart AD, Garcia Rodriguez LA, et al. Antiepileptics and blood dyscrasias: A cohort study. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:1277.

107 Melenhorst JJ, Sorbara L, Kirby M, et al. Large granular lymphocyte leukaemia is characterized by a clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement in both memory and effector CD8(+) lymphocyte populations. Br J Haematol. 2001;112:189.

108 Garrido P, Ruiz-Cabello F, Barcena P, et al. Monoclonal TCRVbeta13.1+/CD4+/NKa+/CD8-/+dim T-LGL lymphocytosis: Evidence for an antigen-driven chronic T-cell stimulation origin. Blood. 2007;109:4890.

109 Ribichini F, Ferrero V, Feola M, et al. Neutropenia in patients treated with thienopyridines and high-dose oral prednisone after percutaneous coronary interventions. J Interv Cardiol. 2007;20:209.

110 Bjornson BH, McIntyre AP, Harvey JM, et al. Studies of the effects of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole on human granulopoiesis. Am J Hematol. 1986;23:1.

111 Kontoghiorghes GJ. Deferasirox: Uncertain future following renal failure fatalities, agranulocytosis and other toxicities. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:235.

112 Risks of agranulocytosis and aplastic anemia. A first report of their relation to drug use with special reference to analgesics. The International Agranulocytosis and Aplastic Anemia Study. JAMA. 1986;256:1749.

113 Melenhorst JJ, Eniafe R, Follmann D, et al. T-cell large granular lymphocyte leukemia is characterized by massive TCRBV-restricted clonal CD8 expansion and a generalized overexpression of the effector cell marker CD57. Hematol J. 2003;4:18.

114 Aymard JP, Aymard B, Netter P, et al. Haematological adverse effects of histamine H2-receptor antagonists. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1988;3:430.

115 van der Klauw MM, Wilson JH, Stricker BH. Drug-associated agranulocytosis: 20 years of reporting in The Netherlands (1974-1994). Am J Hematol. 1998;57:206.

116 Cormican LJ, Schey S, Milburn HJ. G-CSF enables completion of tuberculosis therapy associated with iatrogenic neutropenia. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:649.

117 Jenkins PF, Williams TD, Campbell IA. Neutropenia with each standard antituberculosis drug in the same patient. Br Med J. 1980;280:1069.

118 Tanaka M, Tao T, Kaku K, et al. Agranulocytosis induced by macrolide antibiotics. Am J Hematol. 1995;48:133.

119 Pastor E, Linares M, Grau E. Erythromycin-induced agranulocytosis. DICP. 1991;25:1136.

120 Hennequin C, Bouree P, Halfon P. Agranulocytosis during treatment with mefloquine. Lancet. 1991;337:984.

121 Bonadonna A, Bisetto F, Munaretto G, et al. Agranulocytosis during nifedipine treatment in a hemodialysis patient. Nephron. 1987;47:306.

122 Laurenson IF, Buckoke C, Davidson C, et al. Delayed fatal agranulocytosis in an epileptic taking primidone and phenytoin. Lancet. 1994;344:332.

123 Sharafuddin MJ, Spanheimer RG, McClune GL. Phenytoin-induced agranulocytosis: A nonimmunologic idiosyncratic reaction? Acta Haematol. 1991;86:212.

124 Starkebaum G, Kenyon CM, Simrell CR, et al. Procainamide-induced agranulocytosis differs serologically and clinically from procainamideinduced lupus. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;78:112.

125 Ellrodt AG, Murata GH, Riedinger MS, et al. Severe neutropenia associated with sustained-release procainamide. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:197.

126 Velo GP, Milanino R. Nongastrointestinal adverse reactions to NSAID. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1990;20:42.

127 Hopkinson ND, Saiz GF, Gumpel JM. Haematological side-effects of sulphasalazine in inflammatory arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1989;28:414.

128 Farr M, Symmons DP, Blake DR, et al. Neutropenia in patients with inflammatory arthritis treated with sulphasalazine. Ann Rheum Dis. 1986;45:761.

129 Levitt LJ. Chlorpropamide-induced pure white cell aplasia. Blood. 1987;69:394.

130 Tucker SC, Lynch JP, Ansell BFJr. Chlorpropamide-induced agranuQ locytosis. JAMA. 1977;238:422.

131 Bux J, Ernst-Schlegel M, Rothe B, et al. Neutropenia and anaemia due to carbimazole-dependent antibodies. Br J Haematol. 2000;109:243.

132 Tamai H, Mukuta T, Matsubayashi S, et al. Treatment of methimazoleinduced agranulocytosis using recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (rhG-CSF). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1356.

133 Sato K, Miyakawa M, Han DC, et al. Graves’ disease with neutropenia and marked splenomegaly: Autoimmune neutropenia due to propylthiouracil. J Endocrinol Invest. 1985;8:551.