29

Acne Vulgaris

• A tendency to develop moderate to severe acne can run in families.

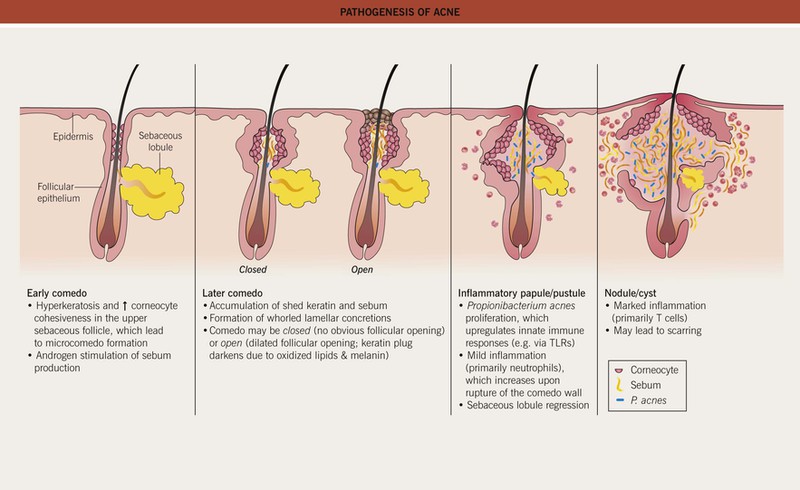

• Multiple factors affecting the pilosebaceous unit contribute to acne pathogenesis (Fig. 29.1), a process that typically begins when androgen production increases at adrenarche.

Clinical Features and Variants of Acne

• Favors the face and upper trunk, sites with well-developed sebaceous glands.

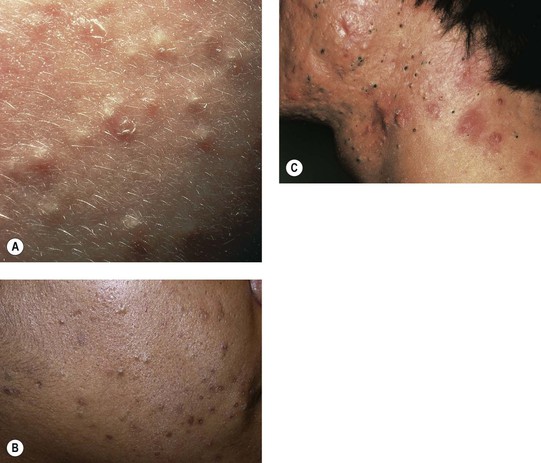

– Closed comedones (whiteheads) are small (~1 mm), skin-colored papules without an obvious follicular opening (Fig. 29.2A,B).

Fig. 29.2 Comedonal acne vulgaris. A Closed comedones highlighted by side lighting. B Open and closed comedones as well as post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation on the cheek. C Prominent open comedones in a patient with scarring cystic acne. A, Courtesy, Ronald P. Rapini, MD; B, Courtesy, Andrew Zaenglein, MD, and Diane Thiboutot, MD.

– Open comedones (blackheads) have a dilated follicular opening filled with a keratin plug, which has a black color due to oxidized lipids and melanin (Fig. 29.2B,C).

– Erythematous papules and pustules (Fig. 29.3A).

Fig. 29.3 Inflammatory acne vulgaris. A Papules, obvious pustules, and atrophic scars are present. B Severe nodulocystic acne. This form is best treated with low doses of isotretinoin initially (± a preceding course of oral antibiotics) to avoid precipitating a flare. A, Courtesy, Andrew Zaenglein, MD, and Diane Thiboutot, MD.

– Nodules and cysts filled with pus or serosanguinous fluid; may coalesce and form sinus tracts (Fig. 29.3B).

– Acne conglobata (severe nodulocystic acne) is classified in the follicular occlusion tetrad along with dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pilonidal cysts (see Chapter 31); it is also a part of pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne conglobata (PAPA) and pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) syndromes.

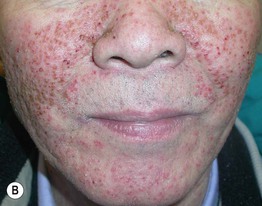

• Inflammatory acne commonly results in post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, especially in patients with darker skin, which fades slowly over time (Fig. 29.4A); nodulocystic acne (and less frequently other inflammatory > comedonal forms) often leads to pitted (Fig. 29.4B) or hypertrophic scars (the latter especially on the trunk; see Fig. 81.4).

Post-Adolescent Acne

Acne Excoriée

Acne Fulminans

• Favors boys 13 to 16 years of age.

• Coalescence into painful, oozing, friable plaques with hemorrhagic crusting, erosion/ulceration, and eventual scarring (Fig. 29.5).

Fig. 29.5 Acne fulminans. Inflamed, friable papulopustules and plaques with erosions, oozing, and formation of granulation tissue. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• DDx: an acne fulminans-like flare occasionally develops upon initiation of isotretinoin therapy for acne, and acne fulminans can be associated with synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome (see Chapter 21).

• Rx: isotretinoin (low dose initially with slow escalation) plus prednisone.

Solid Facial Edema (Morbihan’s Disease)

• Woody induration ± erythema of the central face in the setting of chronic inflammation due to acne vulgaris or rosacea (Fig. 29.6).

Neonatal Acne (Neonatal Cephalic Pustulosis) (See Chapter 28)

Infantile Acne

• Ages 3 months to 2 years; favors boys.

• Facial comedones, papulopustules, and cysts as in classic acne (Fig. 29.7); may result in scarring.

Fig. 29.7 Infantile acne. Presentations can range from scattered papulopustules (A) to multiple coalescing papulonodules and inflammatory cysts (B). If the latter child failed to improve with a topical retinoid plus an oral antibiotic, consideration would be given to oral isotretinoin. Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

Contact Acne

Chloracne

• Comedones and cystic papulonodules develop within 2 months of exposure, favoring malar and retroauricular areas of the face (see Fig. 12.18) as well as the axillae and scrotum; often persists for years.

Drug-Induced Acne and Acneiform Eruptions

• Systemic CS can trigger an eruption of monomorphous follicular papulopustules favoring the upper trunk (Fig. 29.8).

Fig. 29.8 Acneiform eruption secondary to systemic corticosteroid therapy. Abrupt eruption of monomorphous follicular papulopustules on the trunk. Courtesy, Scott Jackson, MD, and Lee T. Nesbitt, Jr., MD.

• Acneiform eruptions represent a frequent side effect of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors (e.g. cetuximab, erlotinib) used to treat solid tumors; patients present with follicular pustules and papules on the face (Fig. 29.9), scalp, and upper trunk, usually 1–3 weeks after beginning treatment, which may correlate with a therapeutic response.

Fig. 29.9 Acneiform eruptions due to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. A, B Numerous monomorphous follicular pustules and crusted papules on the face of two patients treated with erlotinib. A, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; B, Courtesy, Andrew Zaenglein, MD, and Diane Thiboutot, MD.

• Other common causes of drug-induced acne include anabolic steroids, bromides (found in sedatives and cold remedies), iodides (found in contrast dyes and supplements), isoniazid (Fig. 29.10), lithium, phenytoin, and progestins.

Acne Associated with a Syndrome

• Examples include Apert, PAPA, PASH, and SAPHO (see Ch. 21) syndromes.

Evaluation and Treatment of Acne

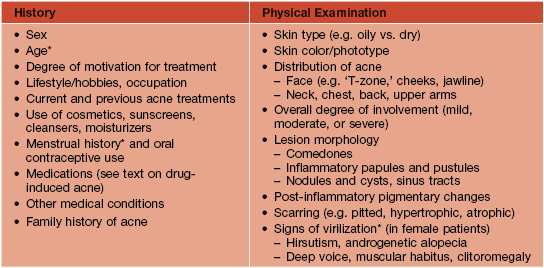

• Table 29.1 lists key components in the history and physical examination of an acne patient.

Table 29.1

History and physical examination of the acne patient.

* Hyperandrogenism should be suspected in children who develop acne between 2 and 7 years of age, in older adolescents/women with irregular menses, and in female patients with signs of virilization; evaluation often includes serum levels of testosterone (total and free), DHEAS, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone (see Fig. 57.10) as well as hand/wrist x-rays to evaluate bone age in prepubertal children.

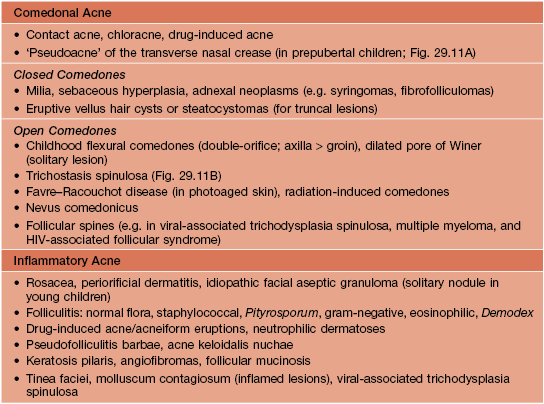

• DDx: presented in Table 29.2.

Table 29.2

Differential diagnosis of acne vulgaris.

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides can mimic comedonal or inflammatory acne.

Fig. 29.11 Disorders in the differential diagnosis of comedonal acne vulgaris. A ‘Pseudoacne’ of the transverse nasal crease in a young child. Note the milia and comedones located along this anatomical demarcation line. B Trichostasis spinulosa. Multiple vellus hairs and keratinous debris are found within the dilated follicular orifices. A, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; B, Courtesy, Judit Stenn, MD.

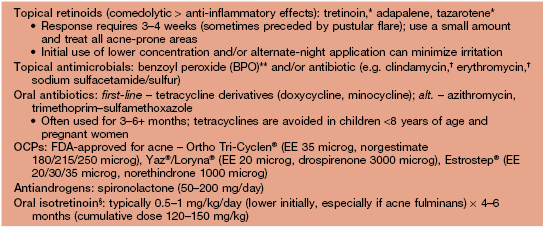

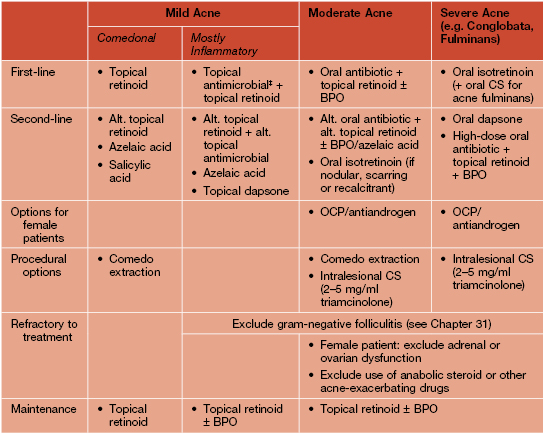

Table 29.3

Treatment of acne vulgaris.

Lack of response should prompt consideration of noncompliance and alternative diagnoses. In general, monotherapy with a topical or oral antibiotic should be avoided. Laser (e.g. 1450-nm diode), light (e.g. blue, intense pulsed), or photodynamic therapies may be of benefit to some patients but are not first-line, and superficial chemical peels (e.g. 20–30% salicylic acid, 30–50% glycolic acid) are occasionally useful to reduce comedones.

* Tretinoin is photolabile and inactivated by BPO (so generally applied at night, separately from BPO); tazarotene is the most irritating of the topical retinoids (see text) and is pregnancy category X.

** Can bleach clothing/bedding and cause contact dermatitis (irritant > allergic); unlike topical antibiotics, bacterial resistance does not occur.

† Increased effectiveness when used in conjunction with BPO or a retinoid.

§ Severe teratogenicity; in the United States, prescribers and patients must register in a risk management program (iPLEDGE™) that requires monthly visits. The most common side effects are cheilitis > mucosal dryness (ocular, nasal) and xerosis (Fig. 29.12).

‡ BPO ± a topical antibiotic may also be used as monotherapy, especially as an initial treatment in a younger patient.

Alt, alternative; EE, ethinyl estradiol; OCP, oral contraceptive pill.

Tips for Topical Therapy

• Even if planning combination therapy, a gradual initial approach can improve tolerance in patients with sensitive skin; for example, a single agent may be used for the first 2–3 weeks (starting every other day for retinoids), followed by slow introduction of a second medication (e.g. transitioning from alternate days to daily).

For further information see Ch. 36. From Dermatology, Third Edition.