Chapter 37 Abused and Neglected Children

Definitions

Incidence and Prevalence

Etiology

Child maltreatment seldom has a single cause; rather, multiple and interacting biopsychosocial risk factors at 4 levels usually exist. At the individual level, a child’s disability or a parent’s depression or substance abuse predispose a child to maltreatment. At the familial level, intimate partner (or domestic) violence presents risks for children. Influential community factors include stressors such as dangerous neighborhoods or a lack of recreational facilities. Professional inaction may contribute to neglect, such as when the treatment plan is not clearly communicated. Broad societal factors, such as poverty and its associated burdens, also contribute to maltreatment. WHO estimates the rate of homicide of children is approximately twofold higher in low-income compared to high-income countries (2.58 vs 1.21 per 100,000 population), but clearly homicide occurs in high-income countries (Table 37-1). Children in all social classes can be maltreated, and child health care professionals need to guard against biases concerning low-income families.

| COUNTRY | DEATHS PER 100,000 CHILDREN* |

|---|---|

| Spain | 0.1 |

| Greece | 0.2 |

| Italy | 0.2 |

| Ireland | 0.3 |

| Norway | 0.3 |

| Netherlands | 0.6 |

| Sweden | 0.6 |

| Korea | 0.8 |

| Australia | 0.8 |

| Germany | 0.8 |

| Denmark | 0.8 |

| Finland | 0.8 |

| Poland | 0.9 |

| UK | 0.9 |

| Switzerland | 0.9 |

| Canada | 1.0 |

| Austria | 1.0 |

| Japan | 1.0 |

| Slovak Republic | 1.0 |

| Belgium | 1.1 |

| Czech Republic | 1.2 |

| New Zealand | 1.3 |

| Hungary | 1.3 |

| France | 1.4 |

| USA | 2.4 |

| Mexico | 3.0 |

| Portugal | 3.7 |

* Deaths include obvious maltreatment and those of undetermined intent.

From UNICEF: A league table of child maltreatment deaths in rich nations. In Inocenti Report Card No 5, Florence, September 2003, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Figure 1b, p 4.

Clinical Manifestations

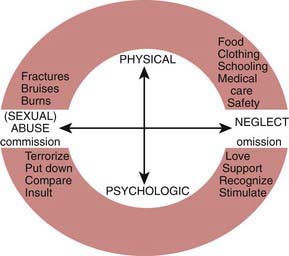

Child abuse and neglect can manifest in many different ways (Fig. 37-1). With regard to physical abuse, a critical element is the lack of a plausible history other than inflicted trauma. As with any medical condition, the onus is on the clinician to carefully consider the differential diagnosis and not jump to conclusions.

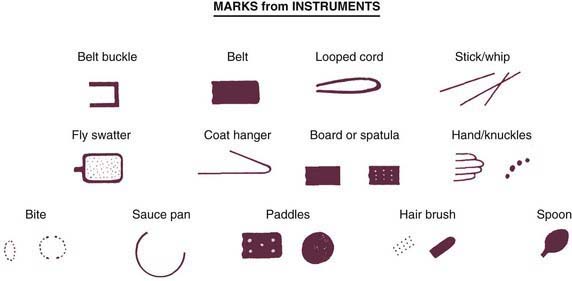

Bruises are the most common manifestation of physical abuse. Features suggestive of inflicted bruises include (1) bruising in a preambulatory infant (occurring in just 2% of infants), (2) bruising of padded and less exposed areas (buttocks, cheeks, under the chin, genitalia), (3) patterned bruising or burns conforming to shape of an object or ligatures around the wrists (Figs. 37-2 and 37-3), and (4) multiple bruises, especially if clearly of different ages. Estimating the age of bruises needs to be done cautiously. Red suggests less than a week, yellow suggests more than 1-2 days. It is very difficult to precisely determine the ages of bruises.

A careful history of bleeding problems in the patient and first degree relatives is needed. If a bleeding disorder is suspected, a platelet count, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio (the ratio of the prothrombin time to a control sample, raised to the power of the International Sensitivity Index), and partial thromboplastin time should be obtained (Chapter 469). More extensive testing should be considered in consultation with a hematologist.

Bites have a characteristic pattern of 1 or 2 opposing arches with multiple bruises (see Fig. 37-2). They can be inflicted by an adult, another child, an animal, or the patient. Bites by a child (younger than approximately 8 yr with primary teeth) typically have a distance of less than 2.5 cm between the canines—often the most prominent bruises. The appearance of animal bites is variable (Chapter 705); they usually have narrower arches than human bites and are often deep. Self-inflicted bites are on accessible areas, particularly the hands. Adult bites raise concern for abuse. Multiple bites by another child suggest inadequate supervision and neglect.

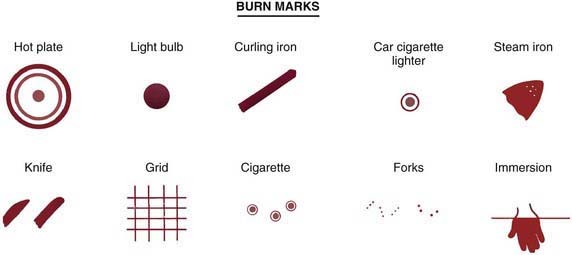

Burns may be inflicted or due to inadequate supervision. Scalding burns may result from immersion or splash (Fig. 37-4; also see Fig. 37-3). Immersion burns, when a child is forcibly held in hot water, show clear delineation between the burned and healthy skin and uniform depth (see Fig. 37-4). They may have a sock or glove distribution. Splash marks are usually absent, unlike when a child inadvertently encounters hot water. Symmetrical burns are especially suggestive of abuse as are burns of the buttocks and perineum. Although most often accidental, splash burn may also result from abuse. Burns from hot objects such as curling irons, radiators, steam irons, metal grids, hot knives, and cigarettes leave patterns representing the object. A child is likely to try to escape from a hot object; thus burns that are extensive and deep reflect more than fleeting contact and are suggestive of abuse.

Neglect frequently contributes to childhood burns (Chapter 68). Children, home alone, may be burned in house fires. A parent taking drugs may cause a fire and may be unable to protect a child. Exploring children may pull hot liquids left unattended onto themselves. Liquids cool as they flow downward so that the burn is most severe and broad proximally. If the child is wearing a diaper or clothing, the fabric may absorb the hot water and cause burns worse than otherwise expected. Some circumstances are difficult to foresee, and a single burn resulting from a momentary lapse in supervision should not automatically be seen as neglectful parenting.

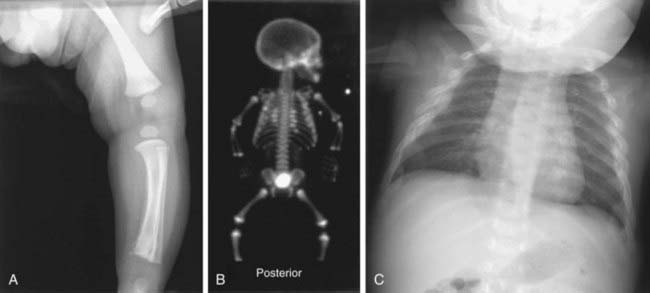

Fractures that strongly suggest abuse include: classic metaphyseal lesions, posterior rib fractures, and fractures of the scapula, sternum, and spinous processes, especially in young children (Table 37-2, Fig. 37-5). These fractures all require more force than would be expected from a minor fall or routine handling and activities of a child. Rib and sternal fractures rarely result from cardiopulmonary resuscitation, even when performed by untrained adults. In abused infants, rib, metaphyseal, and skull fractures are most common. Femoral and humeral fractures in nonambulatory infants are also very worrisome for abuse. With increasing mobility and running, toddlers can fall with enough rotational force to cause a spiral, femoral fracture. Multiple fractures in various stages of healing are suggestive of abuse; nevertheless, underlying conditions need to be considered. Clavicular, femoral, supracondylar humeral, and distal extremity fractures in children older than 2 yr are most likely noninflicted unless they are multiple or accompanied by other signs of abuse. Few fractures are pathognomonic of abuse; all must be considered in light of the history.

Table 37-2 SKELETAL INJURIES FROM ABUSE

COMMON

LESS COMMON

UNCOMMON

* High specificity for abuse in infants.

Modified from Slovis TL, editor: Caffey’s pediatric diagnostic imaging, vol 2, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2008, Mosby/Elsevier.

The evaluation of a fracture should include a skeletal survey in children less than 2 yr of age when abuse seems possible. Multiple films with different views are needed; “babygrams” (1 or 2 films of the entire body) should be avoided. If the survey is normal, but concern for an occult injury remains, a radionucleotide bone scan should be performed to detect a possible acute injury (see Fig. 37-5). Follow-up films after 2 wk may also reveal fractures not apparent initially (see Fig 37-5).

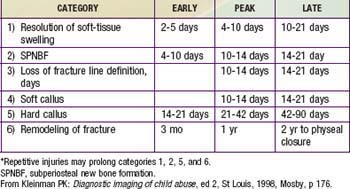

In corroborating the history and the injury, the age of a fracture can only be crudely estimated (Table 37-3). Soft-tissue swelling subsides in 2-21 days. Periosteal new bone is visible within 4-21 days. Loss of definition of the fracture line occurs between 10-21 days. Soft callus can be visible after 10 days and hard callus between 14-90 days. These time frames are shorter in infancy and longer in children with poor nutritional status or a chronic underlying disease. Fractures of flat bones such as the skull do not form callus and cannot be aged.

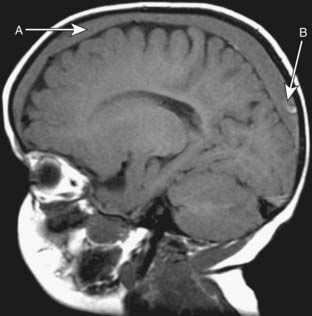

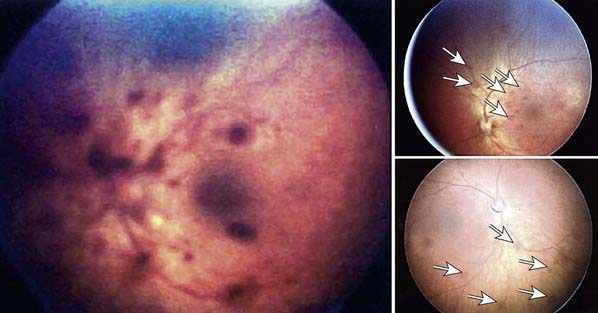

Abusive head trauma (AHT) results in the most significant morbidity and mortality. Abusive injury may be caused by direct impact, asphyxia, or shaking. Subdural hematomas (Fig. 37-6), retinal hemorrhages (especially when extensive and involving multiple layers) (Fig. 37-7), and diffuse axonal injury strongly suggest AHT, especially when they co-occur (Chapter 63). The poor neck muscle tone and relatively large heads of infants make them vulnerable to acceleration-deceleration forces associated with shaking, leading to AHT. Children may lack external signs of injury, even with serious intracranial trauma. Signs and symptoms may be nonspecific, ranging from lethargy, vomiting (without diarrhea), changing neurologic status or seizures, and coma. In all preverbal children, an index of suspicion for AHT should exist when children present with these signs and symptoms.

Retinal hemorrhages are an important marker of AHT (see Fig. 37-7). Whenever AHT is being considered, a dilated indirect ophthalmologic examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist should be performed. Although retinal hemorrhages can be found in other conditions, hemorrhages that are multiple, involve more than one layer of the retina, and extend to the periphery are very suspicious for abuse. The mechanism is likely repeated acceleration-deceleration due to shaking. Traumatic retinoschisis points strongly to abuse.

Other manifestations of abusive head trauma may be seen. “Raccoon” eyes occur in association with subgaleal hematomas after traction on the anterior hair and scalp, or after a blow to the forehead. Neuroblastoma can present similarly, and should be considered (Chapter 492). Bruises from attempted strangulation may be visible on the neck. Choking or suffocation can cause hypoxic brain injury, often with no external signs.

Abdominal trauma accounts for significant morbidity and mortality in abused children (Chapter 66). Young children are especially vulnerable because of their relatively large abdomens and lax abdominal musculature. A forceful blow or kick can cause hematomas of solid organs (liver, spleen, kidney) from compression against the spine, as well as hematoma (duodenal) or rupture (stomach) of hollow organs. Intra-abdominal bleeding may result from trauma to an organ or from shearing of a vessel. More than one organ may be affected. Children may present with cardiovascular failure or an acute condition of the abdomen, often after a delay in care. Bilious vomiting without fever or peritoneal irritation suggests a duodenal hematoma, often due to abuse.

General Principles for Assessing Possible Abuse and Neglect

General Principles for Addressing Child Maltreatment

The heterogeneity of circumstances precludes specific details. The following are general principles.

Butchart A, Kahane T, Harvey AP, et al. Preventing child maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: WHO and International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect; 2006.

Dubowitz H, Bennett S. Physical abuse and neglect of children: key health issues. Lancet. 2007;2(369):1891-1899.

Dubowitz H, DePanfilis D, editors. The handbook for child protection. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications, 2000.

Gilbert R, Kemp A, Thoburn J, et al. Child maltreatment 2: recognizing and responding to child maltreatment. Lancet. 2009;373:167-180.

Legano L, McHugh MT, Palusci VJ. Child abuse and neglect. Curr Prob Pediatr Health Care. 2009;39:25-54.

Reece RM, Christian C, editors. Child abuse: medical diagnosis and management, ed 3, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009.

Barnes PM, Norton CM, Dunstan FD, et al. Abdominal injury due to child abuse. Lancet. 2005;366:234-235.

Bishop N, Aprigg A, Dalton A. Unexplained fractures in infancy: looking for fragile bones. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:251-256.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonfatal maltreatment of infants—United States, October 2005—September 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:336-339.

Chester DL, Jose RM, Aldlyami E, et al. Non-accidental burns in children—are we neglecting neglect? Burns. 2006;32(2):222-228.

Christian CW, Block R, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Abusive head trauma in infants and children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1409-1411.

Curcoy AI, Trenchs V, Moraled M, et al. Do retinal hemorrhages occur in infants with convulsions? Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:873-875.

Di Pietro MA, Brody AS, Cassady CI, et al. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1430-1435.

Drake B, Jolley JM, Lanier P, et al. Racial bias in child protection? A comparison of competing explanations using national data. Pediatrics. 2011;127:471-478.

Dubowitz H, Bennett S. Physical abuse and neglect of children. Lancet. 2007;369:1891-1899.

Forester BR, Petrou M, Lin D, et al. Neuroimaging evaluation of non-accidental head trauma with correlations to clinical outcomes: a review of 57 cases. J Pediatr. 2009;154:573-577.

Fujiwara T, Barber C, Schaechter J, et al. Characteristics of infant homicides: findings from a US multisite reporting system. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e210-e217.

Goldman M, Dagan Z, Yair M, et al. Severe cough and retinal hemorrhage in infants and young children. J Pediatr. 2006;148:835-836.

Guenther E, Powers A, Srivastava R, Bonkowsky JL. Abusive head trauma in children presenting with an apparent life-threatening event. J Pediatr. 2010;157:821-825.

Hymel KP, Makoroff KL, Lakey AL, et al. Mechanisms, clinical presentations, injuries, and outcomes from inflicted versus non-inflicted head trauma during infancy: results of a prospective, multi-centered, comparative study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:922-929.

Kemp AM, Dunstan F, Harrison S, et al. Patterns of skeletal fractures in child abuse: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;337:a1518.

Lantz PE, Sinal SH, Stanton CA, et al. Perimacular retinal folds from childhood head trauma. BMJ. 2004;328:754-756.

Leventhal JM, Martin KD, Asnes AG. Incidence of fractures attributable to abuse in young hospitalized children: results from analysis of a United States database. Pediatrics. 2008;122:599-604.

Levin AV. Retinal hemorrhage in abusive head trauma. Pediatrics. 2010;126:961-970.

Levin AV, Christian CW, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect, Section on Ophthalmology. Clinical report: the eye examination in the evaluation of child abuse. Pediatrics. 2010;126:376-380.

Lindberg D, Makoroff K, Harper N, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases to recognize abuse in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:509-516.

Maguire S. Which injuries may indicate child abuse? Arch Dis Child Pract Ed. 2010;95:170-177.

Maguire S, Mann MK, Sibert J, Kemp A. Are there patterns of bruising in childhood which are diagnostic or suggestive of abuse? A systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(2):182-186.

Mills R, Alati R, O’Callaghan M, et al. Cneglect and cognitive function at 14 years of age: findings from a birth cohort. Pediatrics. 2011;127:4-10.

Peters ML, Starling SP, Barnes-Eley ML, et al. The presence of bruising associated with fractures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:877-881.

Pierce MC, Bertocci GE, Janosky JE, et al. Femur fractures resulting from stair falls among children: an injury plausibility model. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1712-1722.

Pierce MC, Kaczor K, Aldridge S, et al. Bruising characteristics discriminating physical child abuse from accidental trauma. Pediatrics. 2010;125:67-74.

Ravichandiran N, Schuh S, Bejuk M, et al. Delayed identification of pediatric abuse related fractures. Pediatrics. 2010;125:60-66.

Ross AH, Abel SM, Radisch D. Pattern of injury in child fatalities resulting from child abuse. Forensic Sci Int. 2009;188:99-102.

Saperia J, Lakhanpaul M, Kemp A, et al. When to suspect child maltreatment: summary of NICE guidelines. BMJ. 2009;339:b2689.

Scott DA. The landscape of child maltreatment. Lancet. 2009;373:101-102.

Sugar NF. Diagnosing child abuse. BMJ. 2008;337:826-827.

Thackeray JD, Scribano PV, Lindberg DM. Yield of retinal examination in suspected physical abuse with normal neuroimaging. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1066-e1071.

Tung GA, Kumarson RC, Richardson RC, et al. Comparison of accidental and nonaccidental traumatic head injury in children on noncontrast computed tomography. Pediatrics. 2006;118:626-633.

Zimmerman S, Makoroff K, Care M, et al. Utility of follow-up skeletal surveys in suspected child physical abuse evaluations. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(10):1075-1083.

Dubowitz H. Tackling child neglect: a role for pediatricians. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:363-378.

Dias MS, Smith K, DeGuehery K, et al. Preventing abusive head trauma among infants and young children: a hospital-based, parent education program. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):e470-e477.

Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model. Pediatrics. 2009;123:858-864.

Macmillan HL, Wathen CN, Barlow J, et al. Interventions to prevent child maltreatment and associated impairment. Lancet. 2009;373(9659):250-266.

Flaherty EG, Sege R. Barriers to physician identification and reporting of child abuse. Pediatr Ann. 2005 May;34(5):349-356.

Flaherty EG, Sege RD, Griffith J, et al. From suspicion of physical child abuse to reporting: primary care clinician decision-making. Pediatrics. 2008;122:611-619.

Foreman DM, Williams J. Medical law and protection of children. BMJ. 2008;337:a1380.

Jenny C. Supporting paediatricians who work in child maltreatment. Lancet. 2009;373:105-197.

Lane WG, Dubowitz H. Identification and reporting of abusive fractures by orthopaedic surgeons. Clin Orthop Related Res. 2007;261:219-225.

Lane WG, Dubowitz H. Primary care pediatricians’ experience, comfort and competence in the evaluation and management of child maltreatment: do we need child abuse experts? Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:76-83.

American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statements

American Academy of Pediatrics, Hymel KP, et al. Distinguishing sudden infant death syndrome from child abuse fatalities. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Pediatrics. 2006;118:421-427.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Radiology. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1430-1435.

American Academy of PediatricsStirling J, et al. Understanding the behavioral and emotional consequences of child abuse. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect and Section on Adoption and Foster Care. Pediatrics. 2008;122:667-673.

Christian CW, Block R, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Abusive head trauma in infants and children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1409-1411.

Hibbard R, Desch L, et al. Maltreatment of children with disabilities. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1018-1025.

Jenny C. Evaluating infants and young children with multiple fractures. for the Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1299-1303.

Kellogg ND, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1232-1241.

37.1 Sexual Abuse (See Also Adolescent Rape, Chapter 113)

Presentation of Sexual Abuse

Children who have been sexually abused sometimes provide a clear, spontaneous disclosure to a trusted adult. Often the signs of sexual abuse are much more subtle. For some children, behavioral changes are the first indication that something is amiss. Nonspecific behavior changes such as social withdrawal, acting out, increased clinginess or fearfulness, distractibility, and learning difficulties may be attributed to a variety of life changes or stressors. Regression in developmental milestones, including new-onset bed-wetting or encopresis (Chapter 21), is another behavior that caregivers may overlook as an indicator of sexual abuse. Teenagers may respond by becoming depressed, experimenting with drugs or alcohol, or running away from home. Because nonspecific symptoms are very common among children who have been sexually abused, it should nearly always be included in one’s differential diagnosis of child behavior changes.

The Role of the General Pediatrician in the Assessment and Management of Possible Sexual Abuse

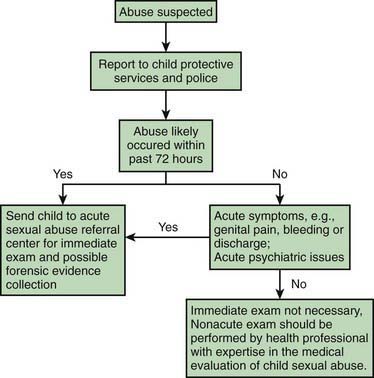

When other medical conditions are not under consideration, have been ruled out, or are less likely than abuse, the triage process for suspected sexual abuse should be activated (Fig. 37-8). Where and how a child with suspected sexual abuse is evaluated should be determined by how long ago the last incident of abuse likely occurred, and whether the child is prepubertal or postpubertal. For the prepubertal child, if abuse has occurred in the previous 72 hr, forensic evidence collection (e.g., external genital, vaginal, anal, and oral swabs, sometimes referred to as a “rape kit”) is often indicated, and the child should be referred to a site equipped to collect forensic evidence. Depending on the jurisdiction, this site may be an emergency department, a child advocacy center, or an outpatient clinic. If the last incident of abuse occurred more than 72 hours prior, the likelihood of recovering forensic evidence is extremely low, and forensic evidence collection is not necessary. For postpubertal females, many experts recommend forensic evidence collection up to 120 hr following the abuse—the same time limit as for adult women. The extended time frame is justified because some studies have demonstrated that semen can remain in the postpubertal vaginal vault for more than 72 hr.

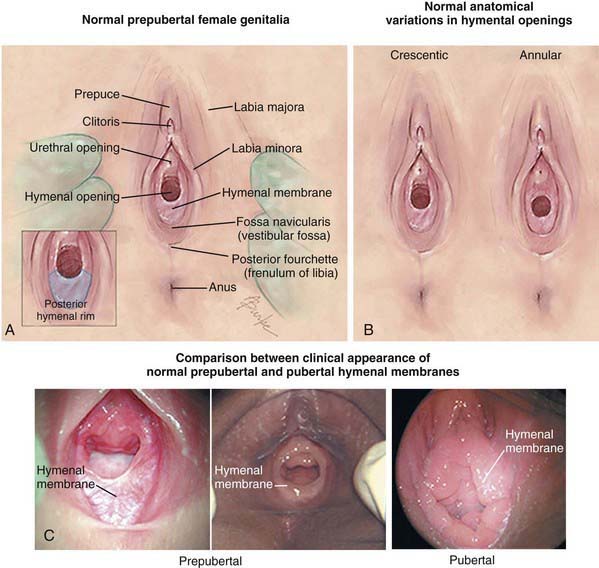

Physical Examination of the Child with Suspected Sexual Abuse

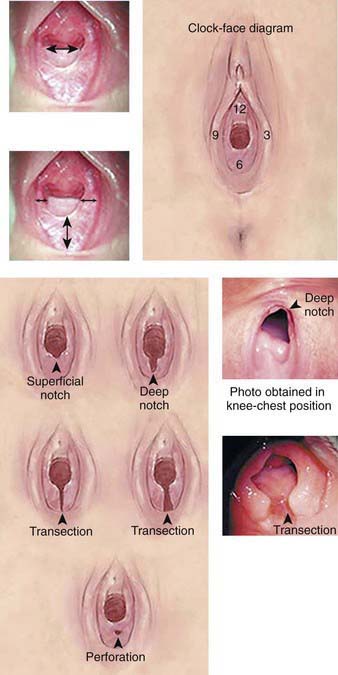

Unfortunately, many physicians are unfamiliar with genital anatomy and examination, particularly in the prepubertal child (Figs. 37-9 and 37-10). Because about 95% of children who undergo a medical evaluation following sexual abuse have normal exams, the role of the primary care provider is often simply to be able to distinguish a normal exam from findings indicative of common medical concerns or trauma. The absence of physical findings can often be explained by the type of sexual contact that has occurred. Abusive acts such as fondling or even digital penetration can occur without causing injury. In addition, many children do not disclose abuse until days, weeks, months, or even years after the abuse has occurred. Because genital injuries can heal rapidly, injuries are often completely healed by the time a child presents for medical evaluation. A normal genital exam does not rule out the possibility of abuse, and should not influence the decision to report to CPS.

Few findings on the genital examination are diagnostic for physical abuse. In the acute time frame, lacerations or bruising of the labia, penis, scrotum, perianal tissues, or perineum are indicative of trauma. Likewise, hymenal bruising and lacerations, and perianal lacerations extending deep to the external anal sphincter indicate penetrating trauma. Several nonacute findings are also concerning for sexual abuse. A complete transection of the hymen to the base between the 4 and 8 o’clock positions (i.e., absence of hymenal tissue in the posterior rim) is considered diagnostic for trauma (see Fig. 37-10). For all of these findings, the cause of injury must be elucidated through the child and caregiver history. If there is any concern that the finding may be the result of sexual abuse, CPS should be notified and a medical evaluation should be performed by an experienced child abuse pediatrician.

Testing for sexually transmitted infections is not indicated for all children, but is warranted in the situations described in Table 37-4. Culture is still considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of gonorrhea (Chapter 185) and chlamydia (Chapter 218) in children. Because obtaining vaginal swabs can be uncomfortable for prepubertal children, a urine specimen for nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) can be collected as a screening test. However, if only NAAT testing is done, the child should NOT receive presumptive treatment at the time of testing. Instead, a positive NAAT test should be confirmed by culture prior to treatment. Because gonorrhea and chlamydia in prepubertal children do not typically cause ascending infection, waiting for a definitive diagnosis before treatment will not increase the risk for pelvic inflammatory disease.

Table 37-4 SITUATIONS INVOLVING A HIGH RISK FOR TRANSMISSION OF SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Workowski KA, Berman SM: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006, MMWR Recomm Rep 55(RR-11):1-94, 2006.

A number of sexually transmitted infections should raise concern for abuse (Table 37-5). In a prepubertal child, a positive culture for gonorrhea beyond the neonatal period, trichomonas beyond 1 yr of age, or chlamydia beyond 3 yr of age indicates that the child has had some contact with infected genital secretions, almost always as a result of sexual abuse. Syphilis (Chapter 210) and HIV are diagnostic for sexual abuse if other means of transmission have been excluded. Because of the potential for transmission either perinatally or through nonsexual contact, the presence of genital warts has a low specificity for sexual abuse. The possibility of sexual abuse should be considered and addressed with the family, especially in children whose warts first appear beyond 3 yr of age. Type 1 or 2 genital herpes is concerning for sexual abuse, but not diagnostic given other possible routes of transmission. For both human papillomavirus and HSV, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends reporting to child protective services unless perinatal or horizontal transmission is considered likely.

Table 37-5 IMPLICATIONS OF COMMONLY ENCOUNTERED SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED (ST) OR SEXUALLY ASSOCIATED (SA) INFECTIONS FOR DIAGNOSIS AND REPORTING OF SEXUAL ABUSE AMONG INFANTS AND PREPUBERTAL CHILDREN

| ST/SA CONFIRMED | EVIDENCE FOR SEXUAL ABUSE | SUGGESTED ACTION |

|---|---|---|

| Gonorrhea* | Diagnostic† | Report‡ |

| Syphilis* | Diagnostic | Report‡ |

| HIV§ | Diagnostic | Report‡ |

| Chlamydia trachomatis* | Diagnostic† | Report‡ |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Highly suspicious | Report‡ |

| Condylomata acuminate (anogenital warts) | Suspicious | Report‡ |

| Genital herpes* | Suspicious | Reportঠ|

| Bacterial vaginosis | Inconclusive | Medical follow-up |

* Report if not likely to be perinatally acquired and rare nonsexual vertical transmission is excluded.

† Although culture is the gold standard, current studies are investigating the use of nucleic acid amplification tests as an alternative diagnostic method.

‡ Report to the agency mandated to receive reports of suspected child abuse.

§ Report if not likely to be acquired perinatally or through transfusion.

¶ Report unless a clear history of autoinoculation is evident.

From MMWR 2006 STD guidelines. Adapted from Kellogg N, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect: The evaluation of sexual abuse in children, Pediatrics 116:506–512, 2005.

Adams JA, Kaplan RA, Starling SP, et al. Guidelines for medical care of children who may have been sexually abused. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007:20163-20172.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of sexual abuse in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116:506-512.

Berkoff MC, Zolotor AJ, Makoroff KL, et al. Has this prepubertal girl been sexually abused? JAMA. 2008;300:2779-2792.

Black CM, Driebe EM, Howard LA, et al. Multicenter study of nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in children being evaluated for sexual abuse. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:608-612.

Centers for Disease Control and PreventionWorkowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

DeLago C, Deblinger E, Schroeder C, et al. Girls who disclose sexual abuse: urogenital symptoms and signs after genital contact. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e281-e286.

Giradet RG, Lahoti S, Howard LA, et al. Epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in suspected child victims of sexual assault. Pediatrics. 2009;124:79-86.

MacLeod KJ, Marcin JP, Boyle C, et al. Using telemedicine to improve the care delivered to sexually abused children in rural underserved hospitals. Pediatrics. 2009;123:223-228.

Murray L, Burnham G. Understanding childhood sexual abuse in Africa. Lancet. 2009;373:1924-1926.

Paras ML, Murad MH, Chen LP, et al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of somatic disorders. JAMA. 2009;302:550-561.

Reading R, Rannan-Eliya Y. Evidence for sexual transmission of genital herpes in children. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:608-613.

37.2 Factitious Disorder by Proxy (Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy)

Berkoff MC, Zolotor AJ, Makoroff KL, et al. Has this prepubertal girl been sexually abused? JAMA. 2008;300:2779-2792.

Girardet RG, Lahoti S, Howard LA. Epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in suspected child victims of sexual assault. Pediatrics. 2009;124:79-86.

Roesler TA, Jenny C. Medical child abuse: beyond Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009.

Stirling JJr, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Beyond Münchausen syndrome by proxy: identification and treatment of child abuse in a medical setting. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1026-1030.