CHAPTER 25 Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair

Case Study

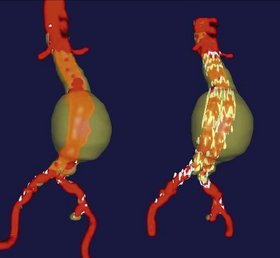

A 70-year-old female with a medical history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and tobacco use presents to the emergency department complaining of 10 hours of severe abdominal and back pain. Physical examination shows a pulsatile, tender epigastric mass. A computed tomography (CT) scan is performed without contrast and shows a 7-cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) (Fig. 25-1).

INDICATIONS FOR ELECTIVE SURGERY

Indications for elective AAA repair include:

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

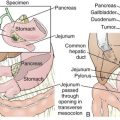

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

Preoperative Considerations

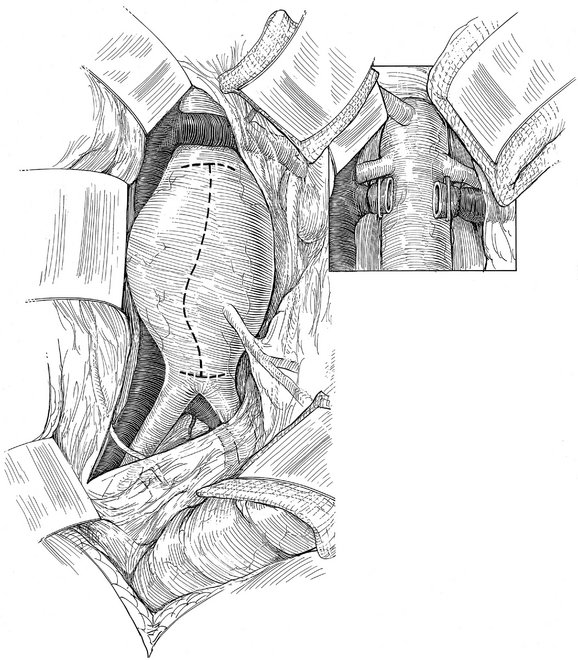

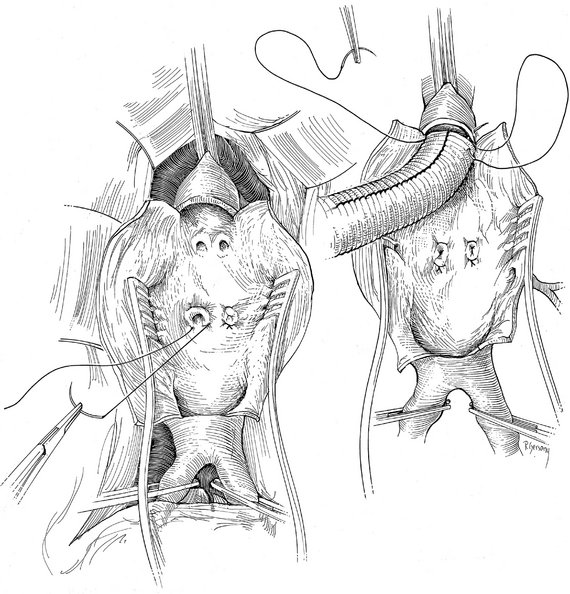

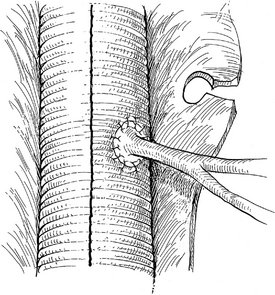

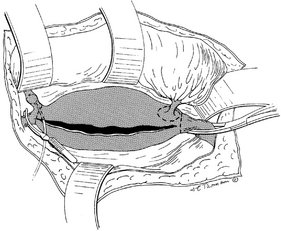

Operative Approach

COMPLICATIONS

AAA STENT GRAFTING

Endovascular aneurysm repair is dependent on sealing of the proximal and distal (iliac) attachment sites. The proximal seal zone must be of small enough diameter to accommodate the chosen endograft, must not be excessively calcified or thrombus-lined, and must be approximately 15 mm long. The common iliac attachment sites must not be aneurysmal themselves, unless the surgeon plans to extend the limbs of the graft into one or both external iliac arteries, covering the internal iliac arteries. Finally, the external and common iliac arteries and the aortic bifurcation must be of sufficiently large caliber to permit introduction of the graft and its delivery system. Preoperative planning and device design are aided by CTA, by three-dimensional modeling of radiographic studies (Fig. 25-6), and by software allowing interactive endograft design.

Curci JA, Sicard GA. Open surgical treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. In: Zelenock GB, editor. Mastery of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2006.

Schermerhorn ML, Cronenwett JL. Abdominal aortic and iliac aneurysms. In Cronenwett JL, editor: Rutherford Vascular Surgery, 6th ed, Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005.

Solis MM, Harvey RL, Hodgson KJ. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: Endovascular repair. In Cameron JL, editor: Current Surgical Therapy, 8th ed, Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2004.