Chapter 17. Abdomen

Lower bowel sounds can be affected by manual manipulation; thus the order of assessment is inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation. Because it is sometimes performed as part of the abdominal assessment, assessment of the anus is included in this chapter.

Rationale

The upper gastrointestinal tract is largely inaccessible to the nurse; thus examination of the abdomen primarily involves assessment of lower gastrointestinal and genitourinary structures. Many common childhood disorders involve the gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems, and the function of these systems can also be altered by factors such as surgery, stress, medications, or the hygienic care that the child receives.

Anatomy and Physiology

Gastrointestinal System

The primary functions of the gastrointestinal tract are the digestion and absorption of nutrients and water, elimination of waste products, and secretion of various substances required for digestion.

The liver, located in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, has several important functions, including biosynthesis of protein; production of blood clotting factors; metabolism of fat, protein, and carbohydrates; production of bile; metabolism of bilirubin; and detoxification.

A primitive gut develops from the endoderm by the third week of gestation. This developing midgut grows so rapidly that by the fourth week of gestation it is too large for the abdominal cavity. Failure of the midgut to rotate and reenter the abdominal cavity at 10 weeks of gestation can produce a variety of disorders, such as omphalocele, and susceptibility to intussusception and bowel obstruction.

Despite the development of the digestive tract in utero, the exchange of nutrients and waste is the function of the placenta. At birth the gastrointestinal tract is still immature and does not fully mature for the first 2 years. Because of this immaturity, many differences exist between the digestive tract of the infant or child and that of the adult. For example, the muscle tone of the lower esophageal sphincter does not assume adult levels until 1 month of age. This lax sphincter muscle tone explains why young infants frequently regurgitate after feedings. Intestinal peristalsis in children is rapid, with emptying time being 2½ to 3 hours in the newborn infant and 3 to 6 hours in older infants and children. Stomach capacity is 10 to 20 ml (0.3 to 0.7 oz) in the neonate, compared with 10 to 200 ml (0.3 to 7 oz) in the 2-month-old infant, 1500 ml (50 oz) in the 16-year-old adolescent, and 2000 to 3000 ml (68 to 101 oz) in the adult. The stomach is round and lies somewhat horizontally until 2 years of age. The parietal cells of the stomach do not produce adult levels of hydrochloric acid until 6 months. The gastrocolic reflex, or movement of the contents toward the colon, is rapid in young infants, as evidenced by the frequency of stools. The intestine, which underwent rapid growth in utero, undergoes further growth spurts when the child is 1 to 3 years of age and again at 15 to 16 years. After birth the musculature of the anus develops as the infant becomes more upright. The child then becomes able to voluntarily control defecation.

Genitourinary System

The kidneys lie posteriorly within the upper quadrants of the abdomen. The kidneys regulate fluid and electrolyte levels in the body through filtration, reabsorption, and secretion of water and electrolytes. Water is excreted in the form of urine. The bladder, located below the symphysis pubis, collects the urine for elimination.

The development of the kidneys begins early in gestation but is not complete until near the end of the first year of life. Until the epithelial cells of the nephrons assume a mature flat shape, filtration and absorption are poor. The loop of Henle gradually elongates, which increases the infant’s ability to concentrate urine, as seen by fewer wet diapers near the first year of life. Increasing bladder capacity also contributes to decreased frequency of voiding. The infant’s bladder capacity is 15 to 20 ml (0.5 to 0.7 oz), compared with 600 to 800 ml (20 to 27 oz) in the adult. The size of the kidneys varies with size and age. The kidneys of infants and children are relatively large in comparison with those of adults and are more susceptible to trauma because of their size.

Equipment for Assessment of Abdomen

▪ Warm stethoscope

▪ Warm hands

▪ Short fingernails

Preparation

Ask the parent or child about a family history of gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract disorders and about the child’s prenatal history (maternal hydramnios is associated with intestinal atresia), mother’s lifestyle during pregnancy, and child’s growth. Inquire about whether the child had imperforate anus, failure to pass meconium, cleft palate or lip, difficulty in feeding, prolonged jaundice, or abdominal wall disorders (e.g., omphalocele or hernia) as a neonate. Ask if the child has had problems with feeding, such as anorexia, vomiting, or regurgitation, or if the child has engaged in fasting or dieting (see Chapter 7 and Chapter 24 for more information about assessment of eating disorders). If the child has had emesis or regurgitation, determine the time of occurrence, frequency, type (Table 17-1), amount, and force (nonprojectile or projectile). (See Table 17-2 for types of vomiting and associated etiologies). Inquire about whether the child has had pain (frequency, intensity, type, location; Table 17-3), itching (location), sleeplessness, swelling, tendency to bruise, thirst, dry mouth, unexplained fever, food allergies, sensitivity to diapers, or alterations in bowel movements or urinary elimination patterns. If there is a problem with bowel movements, inquire about the frequency, amount, consistency, quality, and color of stool (Table 17-4; Table 17-5); use of laxatives and enemas; recent camping trips; and presence of dogs, cats, or turtles. If there are alterations in the pattern of urinary elimination, determine what they are and when they began. If problems with urination or bowel movements occur in toddlers, explore what these problems mean to parents. In the school-age child who experiences recurrent abdominal pain, explore possible stressors and responses to stressors. Inquire about body piercings, tatoos, and environmental factors such as daycare, crowded living conditions, and sharing of utensils and other personal items. When making inquiries of parents regarding bowel habits and vomiting, it is important to avoid asking “Does your child vomit?” or “Does your child have constipation or diarrhea?” because studies suggest that understanding of these terms varies. There is a tendency, for example, with bowel movements, to define diarrhea and constipation by frequency, rather than by consistency of the stool.

| Type of Emesis | Related Findings |

|---|---|

| Undigested formula or food | Rapid expulsion of stomach contents before digestion has occurred. |

| Yellow; might smell acidic | Contents originated in stomach. |

| Dark green (bile-stained) | Contents originated below the ampulla of Vater. |

| Dark brown, foul odor | Emesis produced by intestinal obstruction. |

| Bright red/dark red | Bright red signifies fresh bleeding. Dark red signifies old blood or blood altered by gastric secretions. |

| Description of Vomiting | Associated Symptoms | Possible Etiology |

|---|---|---|

| Acute vomiting |

Diarrhea

Fever

Abdominal pain or cramping (except with cholera infections)

Nausea

Meningeal symptoms (Shigella and

Salmonella groups)

Upper respiratory symptoms (found with Rotavirus)

|

Infections (e.g., Rotavirus, Norwalk virus,Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli, Giardia lamblia, Vibrio cholerae—cholera) |

| Acute vomiting |

Fever

Irritability

Poor feeding (infants and young children) and anorexia

Pulling at the ear

Complaint of earache

Red, bulging eardrum

|

Acute otitis media |

| Acute vomiting |

Fever

Headache

Irritability

Photophobia

Nuchal rigidity

Positive Kernig’s sign

Positive Brudzinski’s sign

Lethargy

Failure to feed (infants)

High-pitched cry (infants)

Tense or bulging fontanel (infants)

Macular or petechial rash

|

Bacterial meningitis |

| Acute Vomiting |

Periumbilical pain that moves to the right iliac fossa

Fever

Rebound tenderness

|

Appendicitis |

| Acute Vomiting |

Disorientation

Ataxia

Nystagmus

Drowsiness

Hypotension

Dysarthria

|

Alcohol poisoning |

| Vomiting |

Episodic colicky pain

Pallor

Infant/child draws up legs

Red currant-jelly stools

Palpable mass in the line of the colon

Peak incidence in infants between 5 and 7 months

|

Intussusception |

| Persistent vomiting |

Effortless regurgitation or emesis

Frequently found in infants younger than 6 months but also occurs in children

Weight loss or failure to gain adequately (if vomiting is severe)

Anemia

Irritability

Heartburn (older children)

|

Gastroesophageal reflux |

| Episodic vomiting |

Headache

Visual symptoms (blurring, flashing lights, stars, scotomata, photophobia)

Dizziness

Abdominal pain

Strong family history of migraine

Local weakness

Sensory disturbances

|

Migraine |

| Recurrent vomiting, possibly hematemesis |

Stabbing, burning pain that radiates to the back

Chronic abdominal pain

Family history

Use of alcohol or tobacco or ulcerogenic drugs

Presence of stress

Presence of bacterium

Helicobacter pylori

|

Peptic ulcer disease |

| Vomiting (morning, with or without feeding, becomes increasingly projectile) |

Headache on waking or with sneezing

Clumsiness

Spasticity

Irritability

Weakness

Seizures

Positive Babinski’s sign

Decreased appetite

|

Brain tumor |

| Forceful vomiting (non bile-stained, progressive) |

Dehydration

Weight loss

Infant hungry following vomiting

Visible peristalsis in the left hypochondrium

Palpable mass between the umbilicus and right costal margin

Usually presents in infants 3 to 6 weeks

|

Pyloric stenosis |

| Location | Characteristics | Possible Age Group | Etiology | Related Factors | Associated Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower abdomen, flank | Severe, colicky | Adolescent | Urolithiasis |

▪ Hypercalciuria

▪ Urinary tract infection

|

▪ Restlessness

▪ Dysuria

|

| Lower abdomen, especially suprapubic | Constant | Any | Cystitis |

▪ Bubble baths

▪ Tight jeans

▪ Nylon panties

▪ Sexual activity

|

▪ Urinary frequency

▪ Dysuria

|

| Lower abdomen | Any | Obstruction |

▪ Adhesions related to surgery

▪ Ingestion of hairballs or trichobezoars

▪ Developmental or psychologic problems

|

▪ Frequent tinkling sounds (early obstruction) or high-pitched rumbles

▪ Diminished bowel sounds (late obstruction)

▪ Absence of bowel sounds (total obstruction)

|

|

| Lower abdomen | Acute or chronic, crampy | Older school-age or adolescent | Ulcerative colitis |

▪ Infection

▪ Dietary habits

▪ Familial tendency

|

▪ Diarrhea

▪ Blood in stools

▪ Growth failure

|

| Bilateral, lower abdomen | Constant | Adolescent | Pelvic inflammatory disease |

▪ Multiple sex partners

▪ Alcohol/drug use

▪ Begins during or within week of menses

|

▪ Guarding upon palpation

▪ Fever

▪ Pain with movement

▪ Walks slightly bent over and tends to hold abdomen

|

| Constant | Adolescent | Endometriosis | ▪ Menses | ||

| Constant, crampy | Adolescent | Ectopic pregnancy | ▪ Amenorrhea | ▪ Morning vomiting | |

| Constant, crampy | Any | Constipation |

▪ Spinal injury

▪ Meningomyelocele

▪ Use of anticholinergics, laxatives

▪ Eating disorders

|

▪ Lack of stooling

▪ Bloating

▪ Presence of a mass

|

|

| Nonspecific | Chronic | School-age adolescent | Psychogenic |

▪ Abuse

▪ Depression

▪ Eating disorders

▪ Minor adjustment problems

|

▪ Pain might interfere with stressful activities but not with pleasurable ones

▪ Can be associated with specific situations

▪ Eyes remain closed during palpation

|

| Generalized | Any | Streptococcal pharyngitis | ▪ Infection |

▪ Erythematous pharynx

▪ Fever

▪ Pain

|

|

| Periumbilical | Crampy | Older school-age or adolescent | Crohn’s disease |

▪ Infection

▪ Dietary habits

▪ Familial tendency

|

▪ Weight loss

▪ Anorexia

▪ Poor growth

|

| Colicky | Any | Lactose intolerance |

▪ Symptoms occur after milk ingestion

▪ Cultural and hereditary factors

|

▪ Borborygmi

▪ Abdominal distention

▪ Watery stools

|

|

| Crampy | Any | Gastroenteritis | ▪ Infection |

▪ Vomiting

▪ Diarrhea

▪ Dehydration

▪ Fever

|

|

| Constant, upon deep inspiration | Any | Pneumonia |

▪ Infection

▪ Aspiration

|

▪ Cough

▪ Fever

▪ Malaise

▪ Rales

|

|

| Colicky | Any | Diabetic ketoacidosis | ▪ Absent or inadequate supply of insulin |

▪ Polydipsia

▪ Polyuria

▪ Headache

▪ Kussmaul’s respirations

|

|

| Periumbilical (nontender) in early stages followed by generalized and then right lower quadrant pain (tender) | Constant, increasing | Preschool, school-age, adolescent | Appendicitis |

▪ Hardened fecal material

▪ Parasites

▪ Foreign bodies

|

▪ Anorexia

▪ Vomiting

▪ Fever

▪ Leukocytosis

▪ Rebound tenderness

▪ Flex hip on affected side

|

| Epigastric | Dull ache | Adolescent |

Esophagitis

Hepatitis

|

▪ Self-induced vomiting

▪ Exchange of blood or any bodily fluid or secretion

▪ Fecal-oral transmission

|

▪ Vomiting

▪ Nausea and vomiting

▪ Fever

▪ Anorexia

▪ Pruritus

▪ Jaundice

|

| Sharp, constant, sudden | Adolescent | Pancreatitis |

▪ Alcohol ingestion

▪ Lying supine can aggravate

|

||

| Stabbing, burning, radiates to back | Adolescent | Duodenal ulcer |

▪ Blood group (O)

▪ Familial tendency

▪ Ulcerogenic drugs

▪ Alcohol

▪ Smoking

▪ Helicobacter pylori

▪ Stress

|

▪ Hematemesis

▪ Melena

▪ Anemia

▪ Poor eating habits

|

|

| Epigastric area, right upper quadrant, shoulder, right scapula | Can be dull, crampy, acute, or gradual | Adolescent more common than children | Cholecystitis |

▪ Oral contraceptive use

▪ Ingestion of fatty or acidic foods

|

▪ Nausea

▪ Bloating

▪ Guarding upon palpation

|

| Type of Stool | Related Findings |

|---|---|

| Soft or liquid | Indicative of breastfeeding. |

| Light yellow, pasty; soft or pasty green | Common in formula-fed babies. Stool has been exposed to air for some time, and oxidation has occurred. |

| Black | Can indicate that the child is receiving iron or bismuth preparations or has gastric or duodenal bleeding. |

| Gray or clay colored | Biliary atresia might be present. |

| Undigested food in stool | Common in infants who are unable to completely digest foods, such as corn and carrots. |

| Currant-jelly stool (blood and mucus) | Indicative of intussusception, Meckel’s diverticulum. Found with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). |

| Ribbonlike | Indicative of Hirschsprung’s disease. |

| Frothy, foul smelling, bulky | Steatorrhea. Can indicate cystic fibrosis. |

| Firm, hard stool | Associated with diet, inadequate fluid or fiber intake, encopresis, obstructive disorders, irritable bowel syndrome, chemotherapy, medications, overly rigid toilet training. |

| Diarrhea (watery, bloody) | Can be related to infection (bacterial, viral, parasitic), dietary causes (overfeeding, excessive ingestion of sugar, or ingestion of heavy metals), irritable bowel syndrome. |

| Type of Diarrhea | Pattern of Diarrhea | Common Age Group Affected | Associated Symptoms | Possible Etiologies | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea Related to Infectious Causes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Watery, profuse | Abrupt onset; can persist for more than a week. Can involve significant diarrhea; major cause of dehydration and hospitalization in children. Incubation period 1 to 3 days. Peak incidence in winter in temperate climates. |

6 months to 24 months most affected

Most common cause of severe diarrheal disease and dehydration in infants

|

Upper respiratory infection

Fever ≥38° C (100° F)

Nausea

Vomiting

Abdominal pain

Dehydration (see Table 17-6 for description of degrees of dehydration)

|

Rotavirus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Watery |

Incubation period of 1 to 3 days. Self-limiting; symptoms last 1 to 2 days, but reinfection can occur.

Diarrhea follows sudden onset of nausea and abdominal cramps.

|

All ages |

Low-grade fever

Loss of appetite

Abdominal pain

Nausea

Vomiting

Malaise

Headache

Myalgia

|

Norwalk virus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Green, watery diarrhea with blood and mucus | Can be gradual or abrupt in onset. |

All ages

Common cause of acute gastroenteritis in children in developing countries

|

Fever

Vomiting

Abdominal distention

Appears toxic

Hemolytic uremic syndrome occurs with 10% of infections with enterohemorrhagic E. coli

|

Diarrheagenic E. coli | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Watery diarrhea |

Onset variable.

Diarrhea contains pus and mucus after approximately first 12 hours. Incubation period 1 to 7 days.

|

Majority of cases in children younger than 9 years |

High fever

Convulsions can accompany fever

Appears toxic

Headache

Nuchal rigidity

Abdominal cramps precede stools

|

Shigella groups | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Watery, profuse, foul-smelling diarrhea with blood | Incubation period 1 to 7 days. |

Severe abdominal pain (periumbilical)

Abdominal cramping

Vomiting

Fever

|

Campylobacter jejuni | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Watery, profuse diarrhea containing blood and mucus |

Intermittent, then continuous diarrhea.

Incubation period can be as long as 5 days.

|

Rare in infants younger than one year | Usually characterized by lack of cramping and anal irritation | Cholera | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occasionally bloody diarrhea with mucus |

Rapid onset.

Incubation period 6 to 72 hours for gastroenteritis.

|

Can occur with all ages, but majority of cases are younger than 20 years

Highest incidence in children younger than 5 years

|

Fever

Nausea

Vomiting

Colicky abdominal pain

Can have headache and meningeal symptoms

History of eating poultry or eggs or of handling turtles and other domestic animals

|

Salmonella groups | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bloody diarrhea | More common in winter. Can relapse for weeks. | Commonly occurs in infants and toddlers |

Fever >38.7° Celsius (101.6° Fahrenheit)

Abdominal pain in right lower quadrant

Vomiting

|

Yersinia enterocolitica | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Profuse diarrhea | Self-limiting (improves in 24 hours). | All ages |

Severe abdominal cramping

Nausea

Vomiting

|

Staphylcoccus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diarrhea Related to Parasites | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Large, pale stools with mucus | Threat to immuno-compromised children. Children can be asymptomatic with light infection. | Young children affected less often than adolescents and adults |

Nausea

Vomiting

Distention

Abdominal pain

Respiratory symptoms

|

Strongyloidiasis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diarrhea | Can be asymptomatic. |

Abdominal pain

Distention

|

Trichuriasis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mild diarrhea |

Gradual onset.

Steatorrhea can also occur. Incubation period of 1 to 2 weeks and symptoms last 2 to 4 weeks.

|

Found in areas where there is poor sanitation |

Nausea

Vomiting

Weight loss (can be significant)

Malaise

Flatulence

Cramping

|

G. lamblia (also known as “beaver fever” or “backpacker’s diarrhea”) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bloody, profuse diarrhea | Symptoms appear 2 to 6 weeks after initial infection. | Second leading protozoan cause of death |

Fever

Malaise

Weight loss

Severe abdominal pain

Liver abscess

|

Entamoeba histolytica | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diarrhea Related to Noninfectious Causes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bright red or currant-jelly stools | Diarrhea is painless. Stools can also be tarry. | Most symptomatic cases involve children 10 years and younger | Symptoms vary with whether process is obstructive or inflammatory or involves hemorrhage | Meckel’s diverticulum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ribbonlike, foulsmelling stool | Can have history of delayed passage of meconium stool. |

Constipation

Vomiting

Failure to thrive

Abdominal distention relieved by rectal stimulation or enemas

|

Hirschsprung’s disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bloody diarrhea | Urgency with stooling; diarrhea can be severe. Bleeding can be occult. |

Mild to moderate weight loss

Mild to moderate anorexia

Some growth retardation

Abdominal cramps

|

Ulcerative colitis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diarrhea (can be bloody) | Mild gastrointestinal symptoms can be present for years. |

Abdominal pain

Epigastric pain

Anorexia (can be severe)

Weight loss (can be severe)

Growth retardation

Anal and perianal lesions

Large joint arthritis

|

Crohn’s disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Watery, offensive stool with mucus and undigested food | Short interval between ingestion of food and diarrhea. | Most common cause of chronic diarrhea in children 1 to 5 years |

Child can look healthy

No identifiable pathogen

|

Toddler diarrhea (“pea and carrot diarrhea”) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chronic diarrhea | Diarrhea can be severe and watery in infants with congenital deficiency of lactase. Symptoms begin within 30 minutes to several hours of consuming lactose. | Usually manifests between 3 and 7 years of age |

Pain

Bloating

Flatulence

|

Lactose intolerance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chronic diarrhea with unformed stools | Stools initially bulky; progress to large, loose stools or diarrhea by 6 months of age. Stools frothy and very foul smelling. | Symptoms can begin at birth |

Dyspnea

Chronic cough

Clubbing

Rhinitis

Chronic sinusitis

Nasal polyps

Chronic bronchial pneumonia

Obstructive emphysema

Malabsorption syndrome

Failure to thrive in young children

Gastroesophageal reflux

Rectal prolapse

|

Cystic fibrosis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chronic diarrhea | Changes in stools follow introduction of gluten into the diet. Stools bulky, fatty, foul smelling. |

Failure to thrive

Weight loss

Abdominal distention

Anorexia

Irritability

Muscle wasting

|

Celiac disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It is important that the child be relaxed during abdominal examination, particularly during palpation. Having the child void, if possible, before the examination assists with comfort during the assessment. Flexing the child’s head or hips helps relax abdominal muscles. Asking the child to “suck in” or “puff out” the abdomen helps assess the degree of discomfort present before deeper probing. Flexing the child’s knees permits greater visibility of the anal area. If the toddler or preschooler is apprehensive, having the parent hold the child supine on the lap with legs flexed and dangling can be helpful in completing the assessment. Talking to and playing with the child also assists in examination. Most children are ticklish, so briefly place a hand flat on the abdomen before beginning the examination. A very ticklish child can be assisted by placing the child’s hand over the nurse’s during palpation. During palpation, observe for changes in vocalization (e.g., cry becomes high-pitched) or sudden protective movements that can indicate pain or tenderness.

Assessment of Abdomen

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inspection | |

| Inspect the contour of the abdomen while the infant or child is standing and while he or she is lying supine. |

A pot-bellied or prominent abdomen is normal until puberty, related to lordosis of the spine.

The abdomen appears flat when the child is supine.

Clinical Alert

An especially protuberant abdomen can suggest fluid retention, tumor, organomegaly (enlarged organ), or ascites.

A large abdomen, with thin limbs and wasted buttocks, suggests severe malnutrition and can be seen in children with celiac disease or cystic fibrosis. A depressed abdomen is indicative of dehydration or high abdominal obstruction.

A midline protrusion from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus or the symphysis pubis indicates diastasis recti abdominis.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inspect the color and condition of the skin of the abdomen. Note the presence of scars, ecchymoses, and stomas or pouches. |

Veins are often visible on the abdomen of thin, light-skinned children.

Clinical Alert

Yellowish coloration can suggest jaundice.

Jaundice is found with hepatitis, cirrhosis, and gallbladder disease.

Silver lines (striae) indicate obesity or fluid retention. Scars can indicate previous surgery.

Ecchymoses of soft tissue areas can indicate abuse.

Distended veins indicate abdominal or vascular obstruction or distention.

|

| Inspect the abdomen for movement by standing at eye level to the abdomen. |

Clinical Alert

Visible peristaltic waves nearly always indicate intestinal obstruction, and in the infant younger than 2 months indicate pyloric stenosis. If an infant younger than 2 months is fed, the peristaltic waves become larger and more frequent if stenosis is present.

Failure of the abdomen and thorax to move synchronously can indicate peritonitis (if the abdomen does not move) or pulmonary disease (if the thorax does not move).

|

| Inspect the umbilicus for hygiene, color, discharge, odor, inflammation, herniation, and fistulas. |

Clinical Alert

A bluish umbilicus indicates intraabdominal hemorrhage.

A nodular umbilicus indicates tumor.

Protrusion of the umbilicus indicates herniation. Umbilical hernias protrude more noticeably with crying and coughing. Palpate the umbilicus to estimate the size of the opening.

Drainage from the umbilicus can indicate infection or a patent urachus.

|

| Assessment | Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Auscultation | |||

|

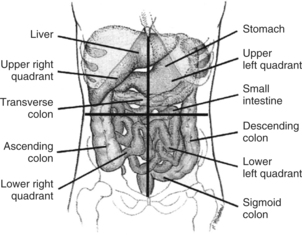

Auscultate for bowel sounds by pressing both the bell and the diaphragm of the stethoscope firmly against the abdomen. Listen in all four quadrants (Figure 17-1) and count the bowel sounds in each quadrant for 1 full minute.

Before deciding that bowel sounds are absent, the nurse must listen for a minimum of 5 minutes in each area where sounds are not heard. Bowel sounds can be stimulated, if present, by stroking the abdomen with a fingernail.

|

Normal bowel sounds occur every 10 to 30 seconds and are heard as gurgles, clicks, and growls.

Clinical Alert

High-pitched tinkling sounds indicate diarrhea, gastroenteritis, or obstruction.

Absence of bowel sounds can indicate peritonitis or paralytic ileus.

|

||

| Percussion | |||

| Using indirect percussion, systematically percuss all areas of the abdomen. | Dullness or flatness is normally found along the right costal margin (see Figure 17-1) and 1 to 3 cm (0.4 to 1.2 in) below the costal margin of the liver. | ||

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

|

Dullness above the symphysis pubis can indicate a full bladder in a young child and is normal. Tympany is normally heard throughout the rest of the abdomen.

Clinical Alert

If liver dullness extends lower than expected, an enlarged liver might be suspected.

Dullness in areas in which tympany would normally be expected can indicate tumor, ascites, pregnancy, or a full bowel.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Palpation | |

| If the child complains of pain in an abdominal area, palpate that area last. | |

| Using superficial palpation, assess the abdomen for tenderness, superficial lesions, muscle tone, turgor (pinch the skin into a fold), and cutaneous hyperesthesia (pick up a fold of skin but do not pinch). Superficial palpation is performed by placing the hand on the abdomen and applying light pressure with the fingertips, using a circular motion. Note areas of tenderness. |

Clinical Alert

Sudden protective behaviors (e.g., grabbing the hand of the nurse), withdrawal, or a tense facial expression can indicate apprehension, pain, or nausea.

Pain on picking up a fold of abdominal skin indicates hyperthesia, which can be found with peritonitis.

Pain that is poorly localized, vague, and periumbilical can indicate appendicitis in the early stage. As the peritoneum becomes inflamed, the pain becomes localized and constant in the right iliac fossa.

|

| Visceral pain, arising from organs such as the stomach and large intestine, is dull, poorly localized, and felt in the midline. Somatic pain, arising from the walls and the linings of the abdominal cavity (parietal peritoneum), is sharp, intense, focused, and well defined and will be at the same dermatomal level as the origin of the pain. Coughing and movement will aggravate pain arising from parietal origins. Do not ask, “Does this hurt?” The child, eager to please, might say yes. A pain measurement scale can help children to rate pain more specifically and to differentiate between pain and fear. During palpation, observe if the child’s eyes are closed; a child with genuine pain will tend to watch the palpating hand closely. | Diffuse pain that mimics the pain associated with appendicitis, along with generalized lymphadenopathy, can indicate mesenteric lymphadenitis. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Perform deep palpation, either by placing one hand on top of the other or by supporting posterior structures with one hand while palpating anterior structures with the other. Palpate from the lower quadrants upward so that an enlarged liver can be detected. |

Discomfort in the epigastrium on deep palpation is related to pressure over the aorta.

The spleen tip can be palpated 1 to 2 cm (0.4 to 0.8 in) below the left costal margin during inspiration in infants and young children and is felt as a soft, thumb-shaped object.

The liver can be palpated 1 to 2 cm (0.4 to 0.8 in) below the right costal margin during inspiration in infants and young children. The liver edge is firm and smooth.

It is often not palpable in older children.

Kidneys are rarely palpable except in neonates.

The sigmoid colon can be palpable as a tender sausage-shaped mass in the left lower quadrant. The cecum can be palpated as a soft mass in the right lower quadrant.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

|

Clinical Alert

Tenderness in the lower quadrants can indicate feces, gastroenteritis, pelvic infection, or tumor.

Tenderness in the left upper quadrant can indicate splenic enlargement or intussusception.

Tenderness in the right upper quadrant can be related to hepatitis or an enlarged liver.

Pain in the costovertebral angle or abdominal pain can indicate upper urinary tract infection.

Tenderness in the right lower quadrant or around the umbilicus can indicate appendicitis.

Rebound tenderness can indicate appendicitis and might be elicited by applying pressure distal to where the child states there is pain.

Pain is experienced in the original area of tenderness when pressure is released.

An enlarged spleen indicates infection or a blood disease.

Palpation of an olive-sized mass in the epigastric area and to the upper right of the umbilicus can indicate pyloric stenosis in the young infant.

An enlarged liver is found with infection, blood dycrasias, sickle cell anemia, or congestive heart failure.

Enlarged kidneys can indicate tumor or hydronephrosis.

A distended bladder can be palpable above the symphysis pubis.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Further assess for peritoneal irritation by performing the psoas muscle test. This test can be performed in a cooperative older child if the nurse is assessing for appendicitis. Have the child flex the right leg at the hip and knee while you apply downward pressure. |

Clinical Alert

Pain suggests appendicitis.

|

| Normally, no pain is felt. | |

| Palpate for an inguinal hernia by sliding the little finger into the external inguinal canal at the base of the scrotum (inguinal hernia is more common in boys) and ask the child to cough. If the child is young, have child laugh or blow up a balloon. |

Clinical Alert

Report the presence of inguinal hernia. An inguinal hernia is felt as a bulge when the child laughs or cries and can also be visible as a mass in the scrotum.

|

| Palpate for a femoral hernia by locating the femoral pulse. Place the index finger on the pulse and the middle or ring finger medially against the skin. The ring finger is over the area where the herniation occurs. |

Clinical Alert

Report the presence of femoral hernia. A femoral hernia is felt or seen as a small anterior mass. Femoral hernia is more commonly found in girls.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| With the child prone, inspect the buttocks and thighs. Examine the skin around the anal area for redness and rash. |

Clinical Alert

Asymmetry of the buttocks and thigh folds indicates congenital hip dysplasia.

Redness and rash can indicate inadequate cleaning after bowel movements, infrequent changing of diapers, or irritation from diarrhea.

|

| Examine the anus for marks, fissures (tears in the mucosa), hemorrhoids (dark protrusions), prolapse (moist tubelike protrusion), polyps (bright red protrusions), and skin tags. |

The anus usually appears moist and hairless.

Clinical Alert

Scratch marks can indicate itching, which can indicate pinworm infestation.

Fissures can indicate passage of hard stools.

Defecation can be accompanied by bleeding if fissures are present. Bleeding can also accompany polyps, intussusception, gastric and peptic ulcers, esophageal varices, ulcerative colitis, infectious diseases, and Meckel’s diverticulum.

Rectal prolapse indicates difficult defecation and often accompanies untreated cystic fibrosis.

Skin tags can indicate polyps and are usually benign.

Lacerations and bruises of anus can indicate abuse.

|

| Stroke the anal area to elicit the anal reflex. |

The anus should contract quickly.

Clinical Alert

A slow reflex can indicate a disorder of the pyramidal tract.

|

Anxiety: related to change in health status.

Pain: related to injury agents.

Constipation: related to insufficient physical activity, pharmacologic agents, megacolon, tumors, electrolyte imbalance, neurologic impairment, poor eating habits, insufficient fluid intake, dehydration, insufficient fluid intake.

Perceived constipation: related to faulty appraisal, cultural/family health beliefs.

Diarrhea: related to stress, anxiety, inflammation, infectious processes, malabsorption, irritation, parasites, contaminants, toxins.

Altered family processes: related to shift in health status of family member.

Fluid volume deficit: related to compromised regulatory mechanisms.

Fluid volume excess: secondary to liver disorders, renal disorders.

Knowledge deficit: related to disease process, dietary alterations, hygienic needs, dietary needs.

Altered parenting: related to physical illness.

Impaired skin integrity: related to nutritional deficit or excess, chemical factors, fluid deficit or excess.

Altered urinary elimination: related to urinary tract infection, anatomic obstruction, sensory motor impairment.

Ineffective therapeutic regimen: related to complexity of therapeutic regimen.