CHAPTER 86 A History of Psychosurgery

The Ancient World

The story of psychosurgery dates back to the ancient world. In fact, one of the earliest forms of neurosurgery—therapeutic trepanation, in which a hole is drilled into the skull to allow access to the brain for medical or mystical purposes—was a widespread practice in many ancient cultures.1–3 Archaeologic evidence shows that holes were drilled into skulls in Europe and North Africa as early as 5000 years ago.4–6 The greatest physician of ancient Greece, Hippocrates, in his work On Injuries of the Head, provided caution about the uses and potential risks of trepanation.1,7 Although it seems that ancient civilizations intended to modify the mind by opening the skull, it may not have been the only indication for this procedure.

Surgical operations for the sole purpose of altering the mind of a person would remain dormant until the 19th century. It did not, however, completely escape the consciousness of the Middle Ages or the Renaissance. Hieronymus Bosch of the Netherlands (c. 1450-1516) was the master painter of “The Cure of Folly,” potentially the earliest great painting depicting a neurosurgical procedure.8 Folly or “madness” was sometimes considered to be a result of a stone on the brain, and in this painting a barber-surgeon is shown incising the patient’s scalp. The inscription on the painting reads, “Master, dig out the stones of folly, my name is ‘Castrated dachshund,’” a term for a simpleton. Although once again not an operation with the intention of lesioning the brain for mental change, it does show the continued perception that the brain is the seat of mentation and its diseases may indeed require surgical opening of the patient’s head.

Burckhardt

Although Egas Moniz is usually credited with originating psychosurgery,9 the modern era of surgery for psychiatric illness is more accurately ascribed to Gottlieb Burckhardt (1836-1907), a Swiss psychiatrist. Burckhardt was the first to perform surgery on the brain for psychiatric disorders.10 Born into a medical family, he went on to study medicine in Basel, Gottingen, and Berlin, and in 1873 he started work at the University of Berne’s Waldau Psychiatric Clinic.10 He subsequently moved to the Prefargier Psychiatry Clinic, where he performed the first topectomy on a patient with psychiatric illness in 1888.

By 1870, Fritsch and Hitzig had already stimulated the cortical surface in dogs and found that some areas elicited motor responses whereas others did not.11 The idea of functional specialization of the brain was being supported by neurophysiologic studies as well. For example, Goltz in 1881 reported on dogs in which neocortical resection induced rage and temporal lobe resection resulted in calmer animals.12

Based on these and other influences, Burckhardt undertook psychosurgical operations on six patients with intractable mental illness, including auditory hallucinations and aggressive behavior.10 In five of the six patients, “primare Verruecktheit” was diagnosed, which is literally translated as primary madness but is perhaps more akin to the schizophrenia of today. Burckhardt published his series of cerebral topectomies (localized resection of the cerebral cortex) in 1891.13 Although not a surgeon, Burckhardt performed these operations himself, and of the six patients, he reported that three displayed partial improvement.10 Burckhardt presented this series of patients at the International Medical Congress in Berlin in 1889.14 His findings drew sharp criticism from the audience.15 As an example, Giuseppe Seppilli, an attendee of the congress, commented that no treatment was better than a bad treatment and thus supposed that these interventions would not be performed in the future.10,16 Even though this early experiment by an isolated Swiss physician was not met with enthusiasm, the concept that surgical interventions on the brain might have an effect on psychiatric disease was born. It was a concept that took a long time to mature from birth to infancy, and until Egas Moniz, the only subsequent attempt at surgery for mental illness was undertaken in 1910 by Puusepp, an Estonian neurosurgeon who surgically disrupted fibers between the frontal and parietal cortices in three manic-depressive individuals with little success.10,17

Moniz

Egas Moniz was a Portuguese neurologist who before embarking on the path of leukotomy, had already made substantial contributions to medicine with his development of cerebral angiography.6 Moniz attended the International Neurological Congress of London in 1935, where Fulton and Jacobsen presented findings in two chimpanzees in which they had performed surgical frontal lobe ablations that resulted in modified behavior.4,6,18 It is interesting to note that although the chimpanzees did exhibit less “experimental neurosis,” they were also less able to perform the experimental tasks.

The London Congress is said to have been the turning point in the history of psychosurgery inasmuch as it seems that the results in these two chimpanzees prompted Egas Moniz to apply experimental treatments to his human patients. Moniz and his neurosurgeon colleague Almeida Lima performed the first prefrontal leukotomy at the Santa Marta Hospital in Lisbon in 1935,6 thereby launching psychosurgery into a new era, one in which experimental surgery was the hallmark of this specialty. Those were not the days of ethics committees and applications for approval of therapies, but rather the era of the application of the “possible” (i.e., the tools of neurosurgery combined with the innovations and experimental creativity of the surgeons). Initially, alcohol was used to destroy the frontal lobe white matter,19 but because the alcohol was difficult to control, the leukotome was invented to make more precise lesions.5 Moniz and Lima had already performed leukotomies on 20 patients only 6 months after the London Congress, such was their fervor in the application of their new technique. They reported recovery in 7 patients, symptomatic improvement in 7, and status quo in 6.20,21 This is probably one of the most important case series in psychosurgical history. The importance of this series lies not only in its demonstration of the potential for reversal of symptoms or “cure” but also in the limited morbidity and zero mortality that was demonstrated, a feat that by neurosurgical standards of the time was not easy to accomplish. The old saying of “first do no harm” was in a sense upheld and allowed further exploration of these techniques. Moniz, who coined the term psychosurgery, was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work in 1949.*

The Limbic System

Only a year after Moniz reported his initial experience with prefrontal lobotomy, Papez published his seminal paper on the hypothesis that a reverberating circuit in the human brain might be responsible for emotion, anxiety, and memory.22 The components of this system included the hypothalamus, septal nuclei, hippocampi, mamillary bodies, anterior thalamic nuclei, cingulate gyri, and their various connections. In 1952, MacLean expanded Papez’ circuit to include paralimbic structures such as the orbitofrontal, insular, and anterior temporal cortices, the amygdala, and the dorsomedial thalamic nuclei.23 The description of a neuroanatomic system in the brain that was implicated in emotion and behavior coincided with the early reports of surgical treatment, and therefore much attention was directed toward finding new targets in the brain to treat. Even today, many of the most effective surgical treatments are directed toward some component of the limbic system, and therefore the term limbic system surgery has been proposed as an alternative to psychosurgery.

Freeman

Walter Freeman was a controversial character in the history of psychosurgery and was also in the audience when Fulton and Jacobsen presented their experience at the International Neurological Congress of London in 1935. Despised by many, he was a man whose intentions were often misunderstood. In an attempt to better understand the man and his methods, the journalist Jack El Hai wrote a fascinating account of his life.24 Walter Freeman, a neurologist, and James Watts, a neurosurgeon, both based in Washington, DC, began their large series of leukotomies in 1936. The original prefrontal lobotomy was performed through bilateral fronto-orbital bur holes, through which a calibrated instrument was passed blindly to the midline and, in a sweeping motion, moved up and down to disrupt the frontal lobe white matter pathways. Among their first 200 patients, reported in 1942, Freeman and Watts noted satisfactory improvement in the majority but also significant complications, including seizures, disordered behavior, and what was termed frontal lobe syndrome.25 Further reports of long-term follow-up by the Connecticut Lobotomy Commission acknowledged postoperative improvement of agitation and disruptive behavior while noting that a number of successful cases experienced what it called “post-leukotomy syndrome.”26,27 Freeman, however, continued to promote this operation, largely drawing benefit from the fact that other therapeutic alternatives were not at all effective. James Watts, however, soon became dissatisfied with the radical fervor and zeal with which Freeman applied the technique and ended their collaboration. The so-called ice-pick procedure, which remains in the enduring conscience of much of the medical community to this day, was developed by Freeman himself and reported as “transorbital leucotomy.”28 This procedure was infamously performed quickly with minimal anesthesia, typically in the immediate postictal phase of a generalized tonic-clonic convulsion induced by tapping a sharp chisel through the orbital roof and thereby damaging the posterior medial orbitofrontal cortex. Toward the latter part of his career, Freeman traveled the United States in a Winnebago camper called the “Lobotomobile” while advocating his transorbital technique in a rather indiscriminate fashion, something that helped cement the negative public perceptions of the technique and its gradual decline.27,29

It is estimated that by 1949, 10,000 leukotomies had been performed in the United States and Britain.4,6 Encouraged by initial optimistic reports, the procedure was even recommended in the United States by the Veterans Administration for the treatment of psychologically disturbed soldiers returning from World War II.30 The procedure most likely gained momentum because it offered an opportunity to treat diseases that were refractory to traditional treatments and resulted in a huge disease burden with significant societal demands. At the time, few satisfactory treatment options existed and psychiatric hospitals were overflowing with the chronic mentally ill. Although the scientific method and rigorous statistical analysis of the results were lacking, transorbital leukotomy enjoyed tolerance by a large body of the medical community because benefit was observed in a substantial percentage of patients.

Freeman’s surgical results, however, were accompanied by a significant risk for death, epilepsy, and intracranial hemorrhage, as well as cognitive and behavioral changes. These complications prompted Fulton and others to call for a less radical and more selective approach to the surgery. By the late 1940s, more precise open surgical procedures were described, including bilateral inferior leukotomy, bimedial frontal leukotomy, orbital gyrus undercutting, cerebral topectomies, and anterior cingulectomies.31–35

Scoville

William Scoville received his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and undertook postgraduate training in psychiatry, neurology, and subsequently neurosurgery. As director of neurosurgery at the Hartford Hospital, Scoville became an influential figure in psychosurgery27 and devised a method of cortical undercutting through bifrontal trephines in which functional cortical areas were separated from white matter tracts with the use of a thin spatula and suction catheter.36 In a sense, this was specific ablation of individual pathways, where Scoville targeted the orbital surface of the frontal lobes, as well as the subcallosal cingulate gyrus, sites that had been shown to control anxiety and affective disorders in both humans and animals.27 He performed hundreds of these procedures with largely satisfactory results and with far fewer complications and behavioral changes than were observed with older techniques.

Stereotactic Surgery

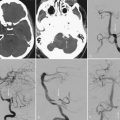

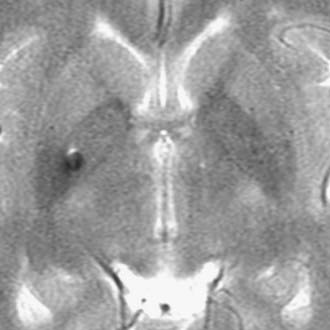

In 1947, Speigel and Wycis introduced stereotactic surgery,37 which allowed placement of more precise lesions in deep parts of the brain with the use of a Cartesian coordinate system for surgical planning. The development of stereotactic surgery was in large part driven by the desire to make reproducible lesions in the brains of large numbers of patients with psychiatric disease. Foltz and White first reported the results of stereotactic anterior cingulotomy in 1962.38 Two years later, Knight reported subcaudate tractotomy.39 In the subsequent decade, Leksell described his experience with anterior capsulotomy and Kelly and coworkers reported limbic leukotomy (subcaudate tractotomy and cingulotomy combined).40 In addition, there have also been reports of hypothalamotomy, bilateral amygdalotomy, and thalamotomy for the treatment of psychiatric illness.41,42 Certainly today, ablative procedures for psychiatric disorders that are performed under stereotactic guidance with controlled radiofrequency generation of lesions are much more refined with precise anatomic localization guided by magnetic resonance imaging, reproducible lesion size, and improved safety profiles.43

Anterior cingulotomy has been the psychiatric surgical procedure of choice in North America for many years. Ballantine and coauthors in 1987 reported on the technique of cingulotomy and noted that up to 60% of patients experienced an improvement in their well-being with regard to depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.44 More recently, Kim,45 Jung,46 Dougherty,47 and their colleagues also reported positive results with this procedure.

Anterior capsulotomy has long been the preferred procedure in Scandinavia and Europe. It involves placement of lesions in the anterior limb of the internal capsule to disrupt pathways from the thalamus to the orbitofrontal cortex. For general anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia, Rück and associates reported a 50% reduction in symptoms across the disease groups.48

Limbic leukotomy essentially combines subcaudate tractotomy and cingulotomy. Montoya and coauthors reported on this treatment in 21 patients with intractable psychiatric disease and noted up to 50% improvement in global functioning.49 Sachdev and Sachdev also reported on 76 patients with treatment-resistant depression in whom bilateral limbic leukotomy resulted in significant improvement of symptoms.50

Decline of Psychosurgery

In 1954, chlorpromazine received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The introduction of the first clinically useful psychotropic drug that became widely available enjoyed a warm welcome that marked the beginning of the end of the era of leukotomy. In just the first year of its availability, approximately 2 million patients received the drug,5 which Freeman described as a chemical lobotomy.6,51 Skepticism regarding the outcomes of surgery and concern over adverse effects fueled acceptance and the widespread use of this new drug. It was especially useful in patients with schizophrenia, a psychiatric illness that is not currently considered an indication for surgery but for which many patients were operated on in the leukotomy era.52 Many new drugs were subsequently developed, and similar to the decline in stereotactic surgery for Parkinson’s disease with the advent of levodopa, the perceived need for the neurosurgeon in psychiatry was largely absent.

In 1967, Freeman, a lone voice in the continued attempt to promote leukotomy, performed the last of such procedures in California. In a dramatic end to this chapter of psychosurgery, Freeman disrupted a blood vessel and the patient died as a result.6 This led to removal of Freeman’s operating privileges and marked the end of a neurosurgical intervention, which would remain dormant for many years to come.

The Public, Legislation, and Ethics

The vivid imagery of Freeman’s “ice-pick” procedure was the focus of public reaction to the entire field of psychosurgery; it completely overshadowed the other psychosurgical procedures that have been tried and the earnest attempts by many investigators to document clinical results and identify appropriate indications for these procedures. The negative stigma entered popular consciousness with the 1962 publication of Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” subsequently turned into a 1975 Milos Forman film that won an Academy Award for Best Picture of the Year.27 Even though favorable results had been achieved with leukotomy and other procedures, the seeming lack of scientific rigor and the fervor with which these procedures were applied and promoted resulted in allegations of abuse and misuse of the procedure. In the 1970s, legislation was passed in the United States that reiterated the importance of ethics boards in the selection of functional neurosurgery patients.5 A report by the U.S. National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research confirmed that psychosurgery displayed efficacy in more than half of the 400 operations performed annually between 1971 and 1973.53 They went further and indicated that no psychological deficits could be attributed to the procedures. Indeed, it seemed that concerns about psychosurgery being used on minority and disadvantaged populations for social control were unsubstantiated. The commission’s conclusions clearly argued against the public perception that psychosurgery was dangerous, ineffective, and purely experimental.

The World Health Organization today defines psychosurgery as “the selective surgical removal or destruction of nerve pathways for the purposes of influencing behavior.”54,55 In light of recent advances, this definition should be updated to include DBS and other neuromodulation treatments (e.g., vagus nerve stimulation [VNS]). National associations of psychiatrists around the world have issued position statements declaring acceptance of these procedures; however, these voices seem to be overpowered by other sectors of the community who continue to denounce all forms of surgical intervention in psychiatry. It is clear that the responsibility lies with neurosurgeons working as part of multidisciplinary groups of specialists to ensure the safe, ethical, and scientific application of all current forms of psychosurgery. In our age of evidence-based medicine and surgery, randomized trials are needed to generate “class 1” evidence for what thus far seem to be effective treatments in properly selected patients.

Future

VNS has been used for the treatment of epilepsy for some time. More recently, its applicability to the treatment of mood disorders such as depression, as well as anxiety disorders, has been discussed.56 The neurophysiologic mechanisms behind its success are not well understood, something that could equally be said of frontal leukotomy in its infancy. Nevertheless, positive mood changes have been found in epileptics undergoing VNS, and clinical evidence is accumulating.57–61

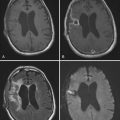

DBS is a relatively recent technique in functional neurosurgery, with well-documented efficacy for movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and pain. What makes DBS attractive to patients and physicians alike is the reversible nature of the treatment. Stimulation parameters such as voltage, frequency, and pulse width can be altered and even switched off. The electrode itself causes minimal damage to the brain parenchyma on insertion. Consequently, DBS has not been restricted to neurological diseases but has also been explored in psychosurgery, often with similar targets as those reported by previous stereotactic psychosurgeons. DBS is a potential modality for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder,62–66 depression,67–70 and Tourette’s syndrome.71–77 Acceptance of this technique in psychiatry is growing, albeit slowly.

The psychiatric community needs to evaluate new and existing treatments of these disorders based on the merits of each intervention rather than their tainted history. Neuroscientists continue to discover molecular mechanisms of psychiatric disease, and as this understanding continues, so will the applicability of surgical alleviation for mental disorders. Neural transplantation, genetic engineering, encoding for neurotransmitters, and improvements in neuroimaging will continue to alter our choice and use of psychosurgical options.78 A central ethical dilemma will continue to be securing informed consent in a patient who lacks the necessary mental faculties to make a rational choice. The future of these therapies will rest on the application of sound clinical and moral guidelines to prevent any possibility of their misuse in the future.

Ballantine HTJr, Bouckoms AJ, Thomas EK, et al. Treatment of psychiatric illness by stereotactic cingulotomy. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22:807-819.

Berrios GE. The origins of psychosurgery: Shaw, Burckhardt and Moniz. Hist Psychiatry. 1997;8(29):61-81.

Bridges PK, Bartlett JR. Psychosurgery: yesterday and today. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;131:249-260.

El-Hai J. The Lobotomist. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

Feldman RP, Alterman RL, Goodrich JT. Contemporary psychosurgery and a look to the future. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:944-956.

Feldman RP, Goodrich JT. Psychosurgery: a historical overview. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:647-657. discussion 657-659

Fins JJ. From psychosurgery to neuromodulation and palliation: history’s lessons for the ethical conduct and regulation of neuropsychiatric research. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:303-319. ix-x

Freeman W. Transorbital leucotomy. Lancet. 1948;2:371-373.

Freeman W, Watts J. Psychosurgery: Intelligence, Emotion and Social Behavior Following Prefrontal Lobotomy for Mental Disorders. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1942.

Greenberg BD, Askland KD, Carpenter LL. The evolution of deep brain stimulation for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Biosci. 2008;13:4638-4648.

Greenberg BD, Malone DA, Friehs GM, et al. Three-year outcomes in deep brain stimulation for highly resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2384-2393.

Kelly D, Richardson A, Mitchell-Heggs N. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy: neurophysiological aspects and operative technique. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123:133-140.

Knight G. The orbital cortex as an objective in the surgical treatment of mental illness. The results of 450 cases of open operation and the development of the stereotactic approach. Br J Surg. 1964;51:114-124.

Kopell BH, Rezai AR. Psychiatric neurosurgery: a historical perspective. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:181-197. vii

Malhi GS, Bartlett JR. Depression: a role for neurosurgery? Br J Neurosurg. 2000;14:415-422.

, 1979 National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, Report and Recommendations. Psychosurgery. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, 1979. Publication No (OS) 77-002

Papez J. A proposed mechanism of emotion. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1937;38:725-743.

Ramsey GV. A short history of psychosurgery. Am J Psychiatry. 1952;108:813-816.

Sachdev PS, Sachdev J. Long-term outcome of neurosurgery for the treatment of resistant depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17:478-485.

Valenstein E. Great and Desperate Cures: The Rise and Decline of Psychosurgery and Other Radical Treatments for Mental Illness. New York: Basic Books; 1987.

1 Missios S. Hippocrates, Galen, and the uses of trepanation in the ancient classical world. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(1):E11.

2 Martin G. Trepanation in the South pacific. J Clin Neurosci. 1995;2:257-264.

3 Rifkinson-Mann S. Cranial surgery in ancient Peru. Neurosurgery. 1988;23:411-416.

4 Swayze VW2nd. Frontal leukotomy and related psychosurgical procedures in the era before antipsychotics (1935-1954): a historical overview. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:505-515.

5 Feldman RP, Goodrich JT. Psychosurgery: a historical overview. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:647-657.

6 Wind JJ, Anderson DE. From prefrontal leukotomy to deep brain stimulation: the historical transformation of psychosurgery and the emergence of neuroethics. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25(1):E10.

7 Withington TT. Hippocrates, Volume III: On Wounds in the Head. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Loeb Classical Library; 1928.

8 Salcman M. The Cure of Folly or the operation for the stone by Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450-1516). Neurosurgery. 2006;59:935-937.

9 Kotowicz Z. Gottlieb Burckhardt and Egas Moniz—two beginnings of psychosurgery. Gesnerus. 2005;62:77-101.

10 Manjila S, Rengachary S, Xavier AR, et al. Modern psychosurgery before Egas Moniz: a tribute to Gottlieb Burckhardt. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25(1):E9.

11 Joanette Y, Stemmer B, Assal G, Whitaker H. From theory to practice: the unconventional contribution of Gottlieb Burckhardt to psychosurgery. Brain Lang. 1993;45:572-587.

12 Goltz F. Ueber die Verrichtungen des Grosshirns. Arch Physiol. 1881;42:1-49.

13 Burckhardt G. Ueber Rindenexcisionen, als Beitrag zur operativen Therapie der Psychosen. Allg Z Psychiatr. 1891;47:463-548.

14 Worcester W. Surgery of the central nervous system (account of the Berlin meeting). Am J Insanity. 1891;XLVII:410-413.

15 Ramsey GV. A short history of psychosurgery. Am J Psychiatry. 1952;108:813-816.

16 Seppilli G. La cura chirurgica delle malattie mentali. Riv Speriment Freniatria Med Leg. 1891;27:369-374.

17 Puusepp L. Alcune considerazioni sugli interventi chirugici nelle malattie mentali. G Accad Med Torino. 1937;100:3-16.

18 Fulton J, Jacobsen C. Fonctions des lobes frontaux; etude comparee chez l’homme et les singes chimpanzes. London. Proceedings of the International Neurological Congress. 1935.

19 Fusar-Poli P, Allen P, McGuire P. Egas Moniz (1875-1955), the father of psychosurgery. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:50.

20 Berrios GE. The origins of psychosurgery: Shaw, Burckhardt and Moniz. Hist Psychiatry. 1997;8(29):61-81.

21 Moniz E. Tentative Operatoires dans le Traitement de Certaines Psychoses. Paris: Masson; 1936.

22 Papez J. A proposed mechanism of emotion. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1937;38:725-743.

23 Maclean PD. Some psychiatric implications of physiological studies on frontotemporal portion of limbic system (visceral brain). Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1952;4:407-418.

24 El-Hai J. The Lobotomist. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

25 Freeman W, Watts J. Psychosurgery: Intelligence, Emotion and Social Behavior following Prefrontal Lobotomy for Mental Disorders. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1942.

26 Moore BE, Friedman S, Simon B, et al. A cooperative clinical study of lobotomy. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1948;27:769-794.

27 Heller AC, Amar AP, Liu CY, et al. Surgery of the mind and mood: a mosaic of issues in time and evolution. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:720-733.

28 Freeman W. Transorbital leucotomy. Lancet. 1948;2:371-373.

29 Mashour GA, Walker EE, Martuza RL. Psychosurgery: past, present, and future. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:409-419.

30 Fins JJ. From psychosurgery to neuromodulation and palliation: history’s lessons for the ethical conduct and regulation of neuropsychiatric research. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:303-319. ix-x

31 Pool JL. Topectomy; a surgical procedure for the treatment of mental illnesses. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1949;110:164-173.

32 Poppen JL. Technic of prefrontal lobotomy. J Neurosurg. 1948;5:514-520.

33 Scoville WB. Selective cortical undercutting as a means of modifying and studying frontal lobe function in man; preliminary report of 43 operative cases. J Neurosurg. 1949;6:65-73.

34 Whitty CWM, Duffield JE, Tow PM. Anterior cingulectomy in the treatment of mental disease. Lancet. 1952;1:475-481.

35 Falconer MA. The surgical treatment of mental disease. Practitioner. 1954;172:692-698.

36 Bridges PK, Bartlett JR. Psychosurgery: yesterday and today. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;131:249-260.

37 Gildenberg PL. The birth of stereotactic surgery: a personal retrospective. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:199-207.

38 Foltz EL, White LEJr. Pain “relief” by frontal cingulumotomy. J Neurosurg. 1962;19:89-100.

39 Knight G. The orbital cortex as an objective in the surgical treatment of mental illness. The results of 450 cases of open operation and the development of the stereotactic approach. Br J Surg. 1964;51:114-124.

40 Kelly D, Richardson A, Mitchell-Heggs N. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy: neurophysiological aspects and operative technique. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123:133-140.

41 Narabayashi H, Nagao T, Saito Y, et al. Stereotaxic amygdalotomy for behavior disorders. Arch Neurol. 1963;9:1-16.

42 Hassler R, Dieckmann N. Relief of obsessive compulsive disorders, phobias and tics by stereotactic coagulation of the rostral intralaminar and medial thalamic nuclei. In: Laitinen L, Livingston K, editors. Surgical Approaches in Psychiatry. Proceedings of the 3rd International Congress of Psychosurgery. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1973:206-212.

43 Feldman RP, Alterman RL, Goodrich JT. Contemporary psychosurgery and a look to the future. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:944-956.

44 Ballantine HTJr, Bouckoms AJ, Thomas EK, et al. Treatment of psychiatric illness by stereotactic cingulotomy. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22:807-819.

45 Kim CH, Chang JW, Koo MS, et al. Anterior cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:283-290.

46 Jung HH, Kim CH, Chang JH, et al. Bilateral anterior cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: long-term follow-up results. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2006;84:184-189.

47 Dougherty DD, Baer L, Cosgrove GR, et al. Prospective long-term follow-up of 44 patients who received cingulotomy for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:269-275.

48 Rück C, Andréewitch S, Flyckt K, et al. Capsulotomy for refractory anxiety disorders: long-term follow-up of 26 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:513-521.

49 Montoya A, Weiss AP, Price BH, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging–guided stereotactic limbic leukotomy for treatment of intractable psychiatric disease. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1043-1049.

50 Sachdev PS, Sachdev J. Long-term outcome of neurosurgery for the treatment of resistant depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17:478-485.

51 Valenstein E. Great and Desperate Cures: The Rise and Decline of Psychosurgery and Other Radical Treatments for Mental Illness. New York: Basic Books; 1987.

52 Cancro R. The introduction of neuroleptics: a psychiatric revolution. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:333-335.

53 National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, Report and Recommendations: Psychosurgery. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, 1979. Publication No (OS) 77-002

54 Kopell BH, Rezai AR. Psychiatric neurosurgery: a historical perspective. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:181-197. vii

55 Fountas KN, Smith JR. Historical evolution of stereotactic amygdalotomy for the management of severe aggression. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:710-713.

56 George MS, Nahas Z, Bohning DE, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation therapy: a research update. Neurology. 2002;59(6 suppl 4):S56-S61.

57 George MS, Rush AJ, Marangell LB, et al. A one-year comparison of vagus nerve stimulation with treatment as usual for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:364-373.

58 Nahas Z, Marangell LB, Husain MM, et al. Two-year outcome of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment of major depressive episodes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1097-1104.

59 Rush AJ, George MS, Sackeim HA, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depressions: a multicenter study. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:276-286.

60 Rush AJ, Marangell LB, Sackeim HA, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a randomized, controlled acute phase trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:347-354.

61 Sackeim HA, Rush AJ, George MS, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depression: efficacy, side effects, and predictors of outcome. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:713-728.

62 Rauch SL, Dougherty DD, Malone D, et al. A functional neuroimaging investigation of deep brain stimulation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:558-565.

63 Burdick A, Goodman WK, Foote KD. Deep brain stimulation for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1880-1890.

64 Jiménez F, Velasco F, Salín-Pascual R, et al. Neuromodulation of the inferior thalamic peduncle for major depression and obsessive compulsive disorder. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:393-398.

65 Greenberg BD, Malone DA, Friehs GM, et al. Three-year outcomes in deep brain stimulation for highly resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2384-2393.

66 Dell’Osso B, Altamura AC, Allen A, et al. Brain stimulation techniques in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: current and future directions. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:966-979. 983

67 Holtzheimer PE3rd, Nemeroff CB. Emerging treatments for depression. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:2323-2339.

68 Glannon W. Deep-brain stimulation for depression. HEC Forum. 2008;20:325-335.

69 Greenberg BD, Askland KD, Carpenter LL. The evolution of deep brain stimulation for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Biosci. 2008;13:4638-4648.

70 Malhi GS, Bartlett JR. Depression: a role for neurosurgery? Br J Neurosurg. 2000;14:415-422.

71 Bloch MH. Emerging treatments for Tourette’s disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10:323-330.

72 Kopell BH, Greenberg B, Rezai AR. Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;21:51-67.

73 Neuner I, Podoll K, Lenartz D, et al. Deep brain stimulation in the nucleus accumbens for intractable Tourette’s syndrome: follow-up report of 36 months. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(4):e5-e6.

74 Welter ML, Mallet L, Houeto JL, et al. Internal pallidal and thalamic stimulation in patients with Tourette syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:952-957.

75 Ackermans L, Temel Y, Visser-Vandewalle V. Deep brain stimulation in Tourette’s Syndrome. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:339-344.

76 Maciunas RJ, Maddux BN, Riley DE, et al. Prospective randomized double-blind trial of bilateral thalamic deep brain stimulation in adults with Tourette syndrome. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:1004-1014.

77 Bajwa RJ, de Lotbinière AJ, King RA, et al. Deep brain stimulation in Tourette’s syndrome. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1346-1350.

78 Troster AI. Clinical neuropsychology, functional neurosurgery, and restorative neurology in the next millennium: beyond secondary outcome measures. Brain Cogn. 2000;42:117-119.