CHAPTER 12. The Adolescent Patient

Maureen Schnur and Kerrie Talbot

OBJECTIVES

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Identify the stages of adolescence and three developmental considerations for each one.

2. Identify two legal issues related to the adolescent patient.

3. List two common responses of the adolescent to surgery/hospitalization and effective communication techniques to use in caring for them.

4. Name two interventions that may enhance care of the adolescent patient with sensory challenges.

5. Identify two suggested approaches to performing a physical examination in an adolescent.

6. Identify two potential risks related to the perianesthesia care of adolescents with body piercing(s).

7. Identify an optimal postoperative position for the obese patient.

8. Identify two safety concerns to discuss with the adolescent upon discharge.

I. CLASSIFICATION BY AGE

A. Eleven through 21 years of age

B. Transition from childhood to adulthood

1. Biologic changes

2. Psychosocial changes

C. Three stages

1. Early adolescence

2. Middle adolescence

3. Late adolescence

II. GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS (Table 12-1)

A. Early adolescence

1. Eleven to 14 years of age

2. Period of growth acceleration

a. Increase in appetite in response to rapid growth

3. Biologic development

a. Girls

(1) Development of breast tissue

(2) Begin to put on fat

(3) Slightly taller and heavier than boys

(4) Beginning of hair growth

(a) Pubic

(b) Axillary

(5) Menarche

b. Boys

(1) Enlargement of testes

(2) Transient gynecomastia

(3) Spermatogenesis

4. Motor development

a. Increase in gross muscle mass

b. Increase in fine motor coordination

c. Prone to ligament tears

d. Awkward, gangly period

5. Psychosocial development

a. Erikson theory

(1) Stage of identity versus role confusion (12-18 years of age)

(a) Corresponds to Freud’s genital stage

(b) Characterized by rapid physical changes

(c) Adolescents become preoccupied with appearance (how they look to others).

b. Freud theory

(1) Genital stage (age 12 and older)

(a) Begins with puberty

(b) Reproductive system and sex hormones mature.

(c) Genital organs become major source of sexual tensions and pleasures.

(d) Period of forming relationships and preparing for marriage

c. Other characteristics

(1) Shy, awkward

(2) Adjusting to middle school

(3) Move from operational thinking to formal, logical operations and increasingly able to:

(a) Manipulate abstractions

(b) Reason from principles

(c) Weigh multiple points of view according to varying criteria

(4) More at ease with same sex

(a) Increased activity with peers

(i) Conformity and cliques

(b) Less activity with family

(5) Increase in self-consciousness

(a) Adolescents meticulous about their appearance

(b) Think everyone is looking at them

(6) Low self-esteem

(7) Increase in rebellious behavior

(8) Increase in independence

(9) Increase in sexual interest

(a) Interest is greater than sexual activity

(b) Often have questions about sexual changes they are experiencing

B. Middle adolescence

1. Fifteen to 17 years of age

2. Biologic development

a. Girls

(1) Height increases.

(2) Breast size increases.

(3) Growth of pubic hair increases.

(4) Sexual maturation occurs.

(5) Shoulder-to-hip proportions are becoming those of an adult woman.

(6) Growth acceleration declines.

(7) Appetite decreases.

b. Boys

(1) Voice changes.

(2) Larynx enlarges.

(3) Muscle mass enlarges.

(4) Strength increases.

(5) Shoulders widen.

(6) Facial hair growth begins.

(7) Height increases rapidly.

(8) Appetite increases.

(9) Size of genitalia increases.

(10) Transient gynecomastia decreases.

c. Both sexes

(1) Acne may develop and be a problem.

(2) Body odor increases as sweat glands further develop.

(3) Dentition is completed.

(4) Sensory and language development are complete.

(5) Capacity of cardiovascular pump increases.

(a) Heart size doubles.

(b) Blood pressure, blood volume, and hematocrit increase.

(6) Lung capacity doubles.

(7) Physiologic need for sleep increases.

3. Motor development

a. Physical endurance increases.

b. Skill in sports increases.

c. Fine and gross muscle coordination increases.

4. Psychosocial development

a. Increased conflicts with parents

b. Mood swings

(1) Impulsive

(2) Impatient

(3) Narcissistic

(4) Moody

c. Test established limits

d. Privacy very important

e. Peer group very important

f. Abstract thoughts increase.

(1) Tend to question and analyze everything

(2) Become more self-centered

5. Sexual development

a. Sexual experimentation begins.

b. Degree of sexual activity varies.

c. Begin to sort out sexual identity

(1) Form beliefs regarding love, honesty, and propriety

d. May choose monogamous or polygamous experimentation, or celibacy

e. Knowledgeable regarding risk of pregnancy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and other sexually transmitted diseases

(1) Knowledge does not necessarily influence behavior.

6. Development of self-concept

a. Period of experimentation

(1) Peers less important

(2) Change style of dress

(3) May change group of friends

b. Deal with inner turmoil

7. Development of relationships

a. Parental relationship strained

(1) May become distant

(2) Dating may become source of conflict.

b. Physical attractiveness remains important.

c. Acceptance by a peer group promotes positive peer relationships and self-esteem.

d. Begin to identify career path

(1) Life skills

(2) Opportunities

e. Positive role models crucial at this stage of development

C. Late adolescence

1. Eighteen to 20 years of age or beyond

2. Biologic development

a. Growth slows

b. No neurological developmental changes apparent

c. Cardiopulmonary capacity relatively mature

3. Psychosocial development

a. Aware of own strengths and limitations

b. Establish own value system

c. Cognition tends to be less self-centered.

(1) Able to express thoughts and feelings about various aspects of life (e.g., justice, patriotism, history)

(2) Idealistic about love, social issues, ethics and lifestyles

d. Social relationships more mature

e. Conformity less important

f. Turbulence with parents decreases.

g. Prepare to leave home

4. Sexual development

a. More commitment to intimate relationships

b. More realistic concept of a partner’s role

5. Self-concept

a. Self-esteem increases.

(1) More stable body image

b. Social roles defined and articulated

(1) Career decisions become important.

(2) Self-concept increasingly tied to role in society (e.g., student, worker, parent)

6. Relationships

a. Separation from parents

(1) Emotional and physical

b. Gain independence from family

| Early Adolescence (11-14 yr) | Middle Adolescence (15-17 yr) | Late Adolescence (18-20 yr) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth |

▪ Rapidly accelerating growth

▪ Reaches peak velocity

▪ Secondary sexual characteristics appear

|

▪ Growth decelerating in girls

▪ Stature reaches 95% of adult height

▪ Secondary sexual characteristics well advanced

|

▪ Physically mature

▪ Structure and reproductive growth almost complete

|

| Cognition |

▪ Explores newfound ability for limited abstract thought

▪ Clumsy groping for new values and energies

▪ Comparison of “normality” with peers of same sex

|

▪ Developing capacity for abstract thinking

▪ Enjoys intellectual powers, often in idealistic terms

▪ Concern with philosophic, political, and social problems

|

▪ Established abstract thought

▪ Can perceive and act on long-range options

▪ Able to view problems comprehensively

▪ Intellectual and functional identity established

|

| Identity |

▪ Preoccupied with rapid body changes

▪ Trying out of various roles

▪ Measurement of attractiveness by acceptance or rejection by peers

▪ Conformity to group norms

|

▪ Modifies body image

▪ Very self-centered, increased narcissism

▪ Tendency toward inner experience and self-discovery

▪ Has rich fantasy life

▪ Idealistic

▪ Able to perceive future implications of current behavior and decisions; variable application

|

▪ Body image and gender role definition nearly secured

▪ Mature sexual identity

▪ Phase of consolidation of identity

▪ Stability of self-esteem

▪ Comfortable with physical growth

▪ Social roles defined and articulated

|

| Relationships with parents |

▪ Defining independence and dependence boundaries

▪ Strong desire to remain dependent on parents while trying to detach

▪ No major conflicts over parental control

|

▪ Major conflicts over independence and control

▪ Low point in parent and child relationship

▪ Greatest push for emancipation; disengagement

▪ Final and irreversible emotional detachment from parents; mourning

|

▪ Emotional and physical separation from parents completed

▪ Independence from family with less conflict

▪ Emancipation nearly secured

|

| Relationships with peers |

▪ Seeks peer affiliations to counter instability generated by rapid change

▪ Upsurge of close, idealized friendships with members of same sex

▪ Struggle with mastery within peer group

|

▪ Strong need for identity to affirm self-image

▪ Behavioral standards set by peer group

▪ Acceptance by peers extremely important—fear of rejection

▪ Exploration of ability to attract opposite sex

|

▪ Peer group recedes in importance in favor of individual friendship

▪ Testing of romantic relationships against possibility of permanent alliance

▪ Relationships characterized by giving and sharing

|

| Sexuality |

▪ Self-exploration and evaluation

▪ Limited dating, usually group

▪ Limited intimacy

|

▪ Multiple plural relationships

▪ Internal identification of heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual attractions

▪ Exploration of “self-appeal”

▪ Feeling of “being in love”

▪ Tentative establishment of relationships

|

▪ Forms stable relationships and attachment to another

▪ Growing capacity for mutuality and reciprocity

▪ Dating as a romantic pair

▪ May publicly identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual

▪ Intimacy involves commitment rather than exploration and romanticism

|

| Psychological health |

▪ Wide mood swings

▪ Intense daydreaming

▪ Anger outwardly expressed with moodiness, temper outbursts, verbal insults and name calling

|

▪ Tendency toward inner experiences, more introspective

▪ Tendency to withdraw when upset or feelings are hurt

▪ Vacillation of emotions in time and range

▪ Feelings of inadequacy common, difficulty asking for help

|

▪ More constancy of emotion

▪ Anger more likely to be concealed

|

III. ADOLESCENT RESPONSE TO SURGERY/HOSPITALIZATION

A. Loss of control

1. A planned procedure (scheduled surgery) allows a greater sense of control than an unplanned (emergency) procedure.

2. Want to be in control

3. May resist dependence

4. May react to loss of control with anger, withdrawal, uncooperativeness, or refusal to follow rules

5. Often feel isolated and unable to obtain adequate support

B. Fear

1. Fear bodily injury, pain and how illness is viewed by peers

a. Activity limitations

b. Appearance

2. May refuse to cooperate if treatment does not fit into lifestyle

3. May project image of “calm and cool” even though they are anxious and/or scared

4. May question everything or appear confident

5. Able to describe degree of pain

C. Separation anxiety

1. May or may not want parents involved

2. May become more dependent on parents

3. Separation from friends increases anxiety.

D. Emotional and behavioral considerations

1. Adolescents use a range of modalities from sophisticated verbal or written expression to motor activity.

2. May regress in behavior

3. Thoughts, feelings, and fears may be shared with friends, especially peers.

4. Major fears and worries

a. Uncertainty about self as a person

b. Concerned about whether or not body, thoughts, and feelings are normal

IV. FAMILY-CENTERED CARE (see Chapter 11)

A. Support system

1. Recognize the increasing maturity and independence of the adolescent, respecting his or her wishes for involvement of family/accompanying significant others as appropriate.

2. Determine the responsible adult accompanying the adolescent.

3. Provide education that it is not unusual for the adolescent to regress, withdraw, or act out.

B. Emergency situations

1. Parents experience stress.

a. Fear and anxiety most common emotions

b. Parent fears that adolescent may:

(1) Experience pain

(2) Suffer permanent changes

(3) Be diagnosed with chronic or terminal illness, or even die

2. Cause of stress is unique to circumstances.

3. Parents may experience guilt.

a. Feel responsible

b. May be submitting adolescent to a painful experience

4. Include family members/support system in adolescent’s care to reduce feelings of helplessness.

a. May choose to access community support (e.g., religious leader, primary physician)

C. Legal issues (see Chapter 5)

1. Bill of Rights (Box 12-1)

a. Facilities may develop and post “bill of rights” for patients and their families.

BOX 12-1

BILL OF RIGHTS FOR CHILDREN AND TEENS

In this hospital, you and your family have the right to:

▪ Respect and personal dignity

▪ Care that supports you and your family

▪ Information you can understand

▪ Quality health care

▪ Emotional support

▪ Care that respects your need to grow, play, and learn

▪ Make choices and decisions

Adapted from Association for the Care of Children’s Health: A pediatric bill of rights. Mt Royal, NJ, 1998, Association for the Care of Children’s Health.

2. Verify guardianship.

3. Consent of minors (Box 12-2)

a. Governed by state laws

b. Exemptions to parental consent for medical treatment

(1) Emancipated minors

(a) Have a child of their own

(b) Married

(c) Live away from home

(d) No longer subject to parental control

(e) Economically self-supporting

(f) Member of military service

(2) Emergencies

(a) May be treated without parental consent during medical emergency

(i) Physician judgment

(ii) Delay would jeopardize health or life of minor

(3) Mature minor rule

(a) Emerging trend in law

(b) Recognizes minor is mature enough to understand nature of illness and risks and benefits of therapy

(c) Should receive treatment at their own request

BOX 12-2

LEGAL AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The nurse or physician must obtain informed consent before any procedure or treatment that is potentially harmful to the child. These include immunizations and participation in research. A parent, an adolescent older than 18 years, or an emancipated minor (a minor child who is no longer dependent upon parents for either emotional or financial support) may give consent. Children able to understand the procedure and its implications should be included in the decision making. In certain cultures, the primary caregiver is not the child’s legal guardian and cannot give consent. To give culturally sensitive care, include all the child’s significant caregivers in the decision-making process.

From Luckmann J: Saunders manual of nursing care, Philadelphia, 1997, WB Saunders.

4. Child abuse and neglect reporting

a. Governed by each state

b. Nurses are mandated reporters in every state.

5. Reproductive health rights

a. Governed by state laws

(1) Disclosure of reproductive health information to parent(s) may or may not be legal (e.g., pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases).

V. PHASES OF PERIOPERATIVE/PROCEDURAL CARE FOR THE ADOLESCENT PATIENT

A. Preadmission/preprocedural assessment (Box 12-3) (see Chapter 15)

1. Medical record review

2. Phone assessment

a. Patients younger than 18 years

(1) Parent/guardian interview

b. Patients 18 years or older

(1) Interview with adolescent

(2) Parent interview with knowledge/agreement of adolescent

(a) Optimizes obtaining more complete history

c. Assess communication barriers (e.g., language, hearing impaired).

(1) Develop plan for resources needed.

d. Determine, plan, and communicate with the health care team for special needs such as:

(1) Disorders with sensory challenges (e.g., autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, pervasive developmental delay)

(a) Plan to minimize stimulation.

(i) Admit to quiet area or room.

(ii) Minimize number of interactions/interventions with patient by organizing care.

[a] Develop plan with accompanying caregiver(s).

(b) Provide option to family to bring favorite familiar comfort objects and/or activities that will help patient cope while waiting for surgery (e.g., music, books, games).

(i) Educate patient/family about potential for risks of damage/loss of personal items, and communicate strategies to minimize possibility.

(c) Determine need for premedication to optimize ability to cope with change in routine.

(2) Obesity

(a) Large wheelchair, appropriate size bed, trapeze on bed, lifting devices, larger-size hospital attire

(b) Plan for need for teaching regarding coughing, deep breathing, and use of incentive spirometry to optimize postoperative respiratory status.

BOX 12-3

PREPARATION OF ADOLESCENTS FOR PROCEDURES AND SURGERY

Major Fears

▪ Loss of control

▪ Altered body image

▪ Separation from peer group

Characteristics of Adolescents’ Thinking

▪ Beginning of formal operational thought and ability to think abstractly

▪ Existence of some magic thinking (e.g., feeling guilty for illness) and egocentrism

▪ Tendency toward hyperresponsiveness to pain

▪ Little understanding of the structure and workings of the body

Preparation

▪ Prepare them in advance, preferably weeks before major events. Advance preparation is vital to adolescents’ ability to cope, cooperate, and comply.

▪ Provide tours and equipment and models to examine. Audiovisual and multimedia computer-based programs may be helpful.

▪ Allow adolescents to be an integral part of decision making about their care, because they can project the future and see long-term consequences and thus are able to understand much more.

▪ Give information sensitively, because adolescents react not only to what they are told but to the manner in which they are told. Explore tactfully what adolescents know and what they do not know.

▪ Stress how much adolescents can do for themselves and how important their compliance and cooperation are to their treatment and recovery; be honest about the consequences.

▪ Allow the adolescent as many choices and as much control as possible. Respect adolescents’ need to exert independence from parents, and remember that they may alternate between dependence and a wish to be independent.

▪ Assure ability to maintain contact with peer group if adolescent desires.

▪ Teach adolescent coping techniques such as relaxation, deep breathing, self-comforting talk and/or the use of imagery.

It is important to remember that the child’s psychosocial developmental stage may not always match his or her chronologic age. Development may be delayed, particularly in chronically ill children. For example, an adolescent who is delayed in development may need to be approached more like a school-age child.

Adapted from Hazinski MF: Manual of pediatric critical care, St Louis, 1999, Mosby.

B. Day of surgery

1. Admission to preoperative/preprocedural area

a. Role of family/accompanying adult(s)

(1) Ascertain and be sensitive to degree to which adolescent wants parent(s)/accompanying adult present.

(2) Be aware that questions may not be answered truthfully in presence of parent(s)/accompanying adult.

(a) Choose time to ask adolescent about sensitive questions that will optimize telling the truth (e.g., when providing adolescent private space to change into hospital attire, this may be an optimal time to ask about use of drugs, alcohol, and smoking).

(3) Encourage parent(s)/responsible adult to accompany adolescent to holding area if requested.

(4) Inform parent(s)/responsible adult of necessity to remain at facility.

b. Developmental considerations (Box 12-4)

(1) Interviewing adolescents (Box 12-5)

(a) Communication approaches

(i) Optimize privacy for interactions.

(ii) Communicate in open and respectful manner.

(iii) Involve in decision-making.

(iv) Provide information sensitively.

(v) Encourage questions regarding fears, options, and alternatives.

(vi) Answer all questions truthfully and honestly.

BOX 12-5

INTERVIEWING ADOLESCENTS

▪ Ensure confidentiality and privacy; interview adolescent without parents.

▪ Show concern for the adolescent’s perspective; “First, I’d like to talk about your main concerns” and “I’d like to know what you think is happening.”

▪ Offer a nonthreatening explanation for the questions you ask: “I’m going to ask a number of questions to help me better understand your health.”

▪ Maintain objectivity; avoid assumptions, judgments, and lectures.

▪ Ask open-ended questions when possible; move to more directive questions if necessary.

▪ Begin with less sensitive issues and proceed to more sensitive ones.

▪ Use language that both the adolescent and you understand.

▪ Restate: reflect back to the adolescent what he or she has said, along with feelings that may be associated with the descriptions.

From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D, eds: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 8, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.

(2) Privacy considerations

(a) Inform adolescent that certain procedures will be conducted only after induction of anesthesia (e.g., hair removal, skin preparation, insertion of urinary catheters).

(b) If appropriate for procedure, allow adolescent to leave undergarments on.

(3) Emotional considerations

(a) May show false bravery to nurse

(b) May be very anxious but not able to verbalize concerns

BOX 12-4

DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO COMMUNICATION APPROACHES (12 YEARS AND OLDER)

| Development | Language Development | Emotional Development | Cognitive Development | Suggested Communication Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

▪ Adolescents are able to create theories and generate many explanations for situations.

▪ They are beginning to communicate like adults.

|

▪ Able to verbalize and understand most adult concepts

|

▪ Beginning to accept responsibility for own actions

▪ Perception of “imaginary audiences”

▪ Need independence

▪ Competitive drive

▪ Strong need for group identification

▪ Frequently have small group of very close friends

▪ Question authority

▪ Strong need for privacy

|

▪ Able to think logically and abstractly

▪ Attention span up to 60 minutes

|

▪ Engage in conversations about adolescent’s interests.

▪ Use photographs, books, diagrams, charts, and videos to explain.

▪ Use collaborative approach and foster and support independence.

▪ Introduce preparatory materials up to 1 week in advance of the event.

▪ Respect privacy needs.

|

Adapted from James SR, Ashwill JW, Droske SC: Nursing care of children, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.

c. Nursing interventions to minimize stress

(1) Give information about proposed procedure to reduce psychological stress and elicit cooperation.

(a) May be concerned regarding cause of illness/need for surgery

(2) Provide information about:

(a) Reasons for tests and procedures

(b) What to expect (e.g., what the adolescent will be asked to do, how long it will take, if discomfort is or isn’t involved)

(c) How the adolescent will feel during and after tests/procedures

(d) When results of tests will be known

(3) Discuss approximate length of time in each phase of hospitalization (e.g., preadmission, OR, Post Anesthesia Care Unit [PACU]).

(4) Inform about when the adolescent/accompanying adult will speak with the surgeon, anesthesia care provider and/or other physician(s).

d. Patient education (see Chapter 3)

(1) Comfort

(a) Teach concepts of interventions they may experience/participate in postprocedure to enhance comfort such as:

(i) Distraction

(ii) Imagery

(iii) Breathing techniques

(iv) Positive self-talk

(v) Moving as one unit (e.g., log rolling after spinal fusion surgery)

(vi) Pillows placed for comfort (e.g., under knees after abdominal surgery to reduce tension on abdomen, to support extremities, for positioning, for splinting abdomen, for coughing exercises)

(vii) Techniques for getting out of bed and turning to reduce pressure on incisions

(2) Allow choices when possible.

(a) Induction of anesthesia

(b) Intravenous insertion

(i) In OR

(ii) In preprocedural area

[a] Interventions to minimize discomfort and anxiety include:

[1] Topical anesthetic agents

[2] Alternative methods (e.g., guided imagery, music, reiki)

(c) Parental/responsible adult presence

(i) Adolescent’s anxiety may be decreased by presence of trusted adult(s) who provide comfort, protection, and encouragement.

(3) Provide information and teaching about intraoperative experience.

(a) Monitoring devices that will be applied (e.g., electrocardiogram, pulse oximeter, blood pressure cuff)

(b) Invasive lines, tubes, or drains that may be inserted as part of the procedure; safety strap that may be secured for transport to PACU

(i) May wake up with these in place

(c) Sensations from anesthetics administered

(d) Endotracheal intubation after “asleep” or loss of consciousness obtained

(i) Inform patients they may experience “sore throat” postoperatively.

(e) Only surgical area exposed for staff to view

(i) Sterile drapes applied around site

(f) Will remain unconscious throughout procedure

(i) Provide reassurance to the adolescent that they do not need to worry about talking or doing anything embarrassing while under anesthesia.

2. Admission assessment (see Chapter 15)

a. Anticipate postoperative complications.

(1) Review and assess body systems.

(2) Note recent or current cold, asthma exacerbation, rash, fever, vomiting, or diarrhea.

(3) Observe verbal and nonverbal behavior before surgery.

(4) Assess for child abuse and neglect.

(a) Follow state law regarding reporting.

(b) Follow facility protocol/policy.

(5) Check vital signs, including heart rate, respirations, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and temperature.

(6) Obtain weight and height.

(a) Optimize privacy.

(i) May be focused on being overweight or underweight

(7) Document allergies and sensitivities (e.g., food, drugs, latex).

(8) Determine use of alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs, or other substances per facility policy/protocol.

(a) Maintain privacy when obtaining history of smoking, drug use, body art, last menstrual period, and other potentially sensitive information.

(9) Ask adolescent about contact lenses, oral appliances, and other cosmetic or medical devices.

(10) Ask adolescent about jewelry, including body piercings, and assess need to insulate or remove.

(a) To insulate:

(i) Tape down with surgical tape.

[a] May apply soft dressing over piercing and tape

(b) Remove if indicated due to potential risks.

(i) Infection

(ii) Obstruction

[a] May be dislodged (e.g., tongue stud)

[b] With tongue studs, may be best to remove in holding area and reinsert as soon as possible in the PACU to avoid interfering with patency

(iii) Increased magnetic pull

[a] Magnetic resonance imaging procedures

(iv) Serve as metal conductor

[a] Risk for burns

(v) May catch on items

[a] Electrocardiogram leads, drapes, accidental tearing of pierced site

(vi) Interference with routine procedures if undisclosed (e.g., unknown genital piercing may interfere with intraoperative insertion of urinary catheter)

(vii) Risk of loss (e.g., navel stud)

(11) Secure personal belongings.

(a) Follow facility policy on safe keeping of personal belongings.

(b) Family/responsible adult may hold items for patient while in tests/procedure/surgery.

C. Physical assessment (see Chapter 15)

1. Approach

a. Use straightforward approach.

b. Involve adolescent in decision of who should be present for exam.

2. Technique

a. Move from head to toe.

b. Perform genital exam in the middle of exam.

(1) Allow ample time for questions and answers.

c. Assure adolescent regarding normal growth and development.

d. Answer questions or concerns regarding what is happening to their bodies.

e. Drape appropriately to preserve dignity.

3. Nursing considerations

a. Admission to hospital or facility may be viewed as a threat to adolescent’s independence, resulting in sense of loss of control.

(1) May react by not cooperating or withdrawing

b. May resent dependency on others and have difficulty accepting restrictions (e.g., dietary)

(1) Explain consequences of not telling the truth regarding eating and/or drinking before procedure.

c. Involve in decision-making and planning.

d. Accept childish methods of coping.

e. Provide support and reassurance as necessary.

f. Provide explanations and consequences of decisions.

4. Conduct sexual assessment.

a. Determine possible pregnancy.

(1) Document last menstrual period.

(2) Conduct pregnancy testing if indicated per facility protocol/policy.

(3) Refer to individual state laws regarding disclosure of reproductive health information.

D. Preoperative teaching (see Chapter 15)

1. Provide information about what will happen.

a. Estimated time frames

(1) Preempt anxiety related to expectations about estimated time frames by educating patient/family about the often dynamic nature of the perioperative environment.

b. Postoperative routine in PACU

(1) Oxygen

(2) Position

(3) Monitoring

(4) Dressing checks

(5) Tubes

(a) Intravenous and/or arterial line(s)

(b) Drainage collection devices

(c) Urinary catheter

(d) Chest tube(s)

(6) Respiratory interventions

(a) Deep breathing

(b) Coughing

(c) Incentive spirometry

(i) May be helpful to practice in patient populations more at risk (e.g., patients having abdominal surgery, obese patients, smokers)

(7) Pain assessment and treatment

(a) Review pain scales.

(b) Identify goal for pain relief.

(c) Coach to help develop coping strategies.

(i) Deep breathing

(ii) Guided imagery

(iii) Positive self-talk statements (e.g., “I can make it through this.”)

(8) Visitation

(a) Provide information on visiting guidelines per facility policy/protocol.

(b) Encourage patient/family to use caution keeping small items on bed during provision of care to patient (e.g., electronic devices may fall to floor while turning patient and be damaged).

(9) Resumption of oral intake

2. Teaching strategies

a. Determine most effective way to communicate necessary information to both adolescent and responsible adult caregiver.

(1) Assess whether it is best to teach adolescent and the adult who will be responsible for care together or separately.

(2) Determine preferred method(s) of learning of adolescent and responsible adult caregiver.

(3) Promote collaborative decision-making.

b. Clearly explain how the body is affected by surgery or procedure.

(1) Provide information openly and honestly.

(2) Use scientific names with explanations.

(3) Use diagrams and printed materials.

c. Provide opportunities for adolescent to express anxieties.

(1) Consider that some adolescents may be embarrassed about peers finding out about certain procedures and may benefit from planning a communication strategy (e.g., patients undergoing circumcision may be more comfortable indicating to peers that they had a similar procedure such as a hernia repair).

E. Intraoperative considerations

1. Provide reassurance before induction.

a. Hold hand.

b. Offer verbal support.

c. Assure preservation of privacy and dignity.

d. Provide for patient safety.

F. Postoperative assessment (see Chapter 50)

1. Respiratory assessment

a. Position airway for optimal ventilation.

(1) Semirecumbent position suggested for obese patients to decrease abdominal pressure on diaphragm

b. Monitor rate and depth of ventilation.

c. Monitor oxygen saturation.

d. Observe for tongue obstruction.

e. Observe for respiratory depression from narcotics and muscle relaxants.

2. Cardiovascular assessment

a. Assess vital signs and perfusion.

b. Heart rate

(1) Awake: 60 to 90 beats per minute

(2) Sleeping: 50 to 90 beats per minute

(3) May be lower if adolescent is athletic

c. Blood pressure (BP)

(1) Systolic: 112 to 128 mm Hg

(2) Diastolic: 66 to 80 mm Hg

3. Thermoregulation (see Chapter 24)

a. Responds to cold environment by increasing metabolism

(1) Increase in oxygen consumption

(2) Shivering

b. Hypothermia

(1) Monitor:

(a) Vital signs including core temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate

(b) Degree of emergence from anesthesia

(c) Continuous electrocardiogram

(i) Dysrhythmias and cardiovascular depression associated with hypothermia

c. Hyperthermia

(1) Overheating

(2) Infection

(a) Preexisting fever versus new onset

d. Emergence delirium (see Chapter 11)

4. Pain assessment (see Chapter 26)

a. Perceive pain on three levels

(1) Physical

(2) Emotional

(3) Mental

b. Able to understand cause and effect of pain

c. Able to describe pain

(1) Verbalize with words such as “ache,” “sore,” “pounding.”

(2) Describe pain intensity and quality.

(a) Express feelings regarding pain.

(b) Identify strategies that have helped with past experiences of pain.

d. Not unusual for adolescents to deal with pain through regressive behavior

(1) Increased dependence on parent

(2) Expect the nurse to know they are in pain.

(3) Believe they should not have to ask for pain medication

e. Concerned with maintaining composure and are embarrassed and ashamed if lose control

f. Observed symptoms of pain include:

(1) Increased muscle tension

(a) Facial grimacing

(b) Muscle rigidity

(2) Withdrawal

(a) Decreased interest in environment and usual activities

(3) Physical response

(a) Decreased motor activity

(i) Reluctant to move

(b) Physical resistance and aggression—unusual unless the adolescent is totally unprepared for the procedure

(4) Vocalization

(a) May grunt, groan, sigh, or use inappropriate language

(b) Rarely cry or scream

g. Pain assessment scales (see Chapters 11 and 26)

(1) Self-report

(a) Visual analog scale

(i) Mark on a line (no pain to worst pain) a point that corresponds to the adolescent’s pain level.

(b) Verbal numerical score

(i) Choose a number from 0 to 10 that corresponds to their pain level (0, no pain; 10, worst pain imaginable).

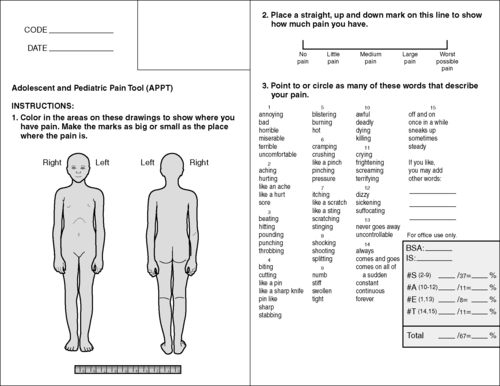

(c) Adolescent and Pediatric Pain Tool (Figure 12-1)

(i) Patient draws on front and back of body outlines to locate pain.

(ii) Indicates pain intensity on a Word Graphic Rating Scale

(iii) Circles words that describe the quality of pain

|

| FIGURE 12-1 ▪

Adolescent and Pediatric Pain Tool.

(From James SR, Ashwill JW, Droske SC: Nursing care of children, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

|

h. Pharmacologic interventions: Analgesics (see Table 11-6)

(1) Opioids

(a) For moderate to severe pain

(b) Routes

(i) Intravenous

[a] Preferred route after major surgery and/or if intravenous line in place

[b] May be administered continuously and/or intermittently

[c] Used for patient-controlled analgesia

[1] Provides steady level of analgesia

[2] Increased risk for respiratory depression

[3] Risk for dependence or addiction very low in patients without a history of prior substance abuse

[4] Not routinely used in outpatient setting

(ii) Epidural, intrathecal

[a] Provides effective analgesia

[b] Increased risk of respiratory depression

[c] May have delayed onset

[d] Requires careful monitoring

[e] Not routinely used in outpatient setting

(iii) Oral

[a] Route of choice for mild to moderate pain when tolerating oral intake

[b] May be as effective as parenteral in appropriate doses

[c] Assess ability to swallow or chew pills and/or swallow liquids.

(iv) Intramuscular or subcutaneous injections

[a] Painful and emotionally upsetting

[b] Absorption unreliable

[c] Avoid injections if possible.

(2) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

(a) Contraindicated in patients with renal disease and those with, or at risk for, actual coagulopathy

(b) May mask fever

(c) May be given in conjunction with opioid(s)

(d) Parenteral

(i) Ketorolac

[a] For moderate to severe pain

[b] May be useful when opioids contraindicated

[c] Only NSAID approved for parenteral analgesia

[d] Limit use to 48 to 72 hours.

(e) Oral

(i) For mild to moderate pain

(ii) May be administered preoperatively

(iii) Naproxen

[a] Longer half-life than other NSAIDs

[b] Suggested dosage: 5 mg/kg orally, every 12 hours as necessary

VI. POSTPROCEDURAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR ADOLESCENTS (see Chapters 11 and 50)

A. Nursing interventions

1. PACU phase I

a. Use safety measures.

(1) Side rails up

(2) When adolescent is emerging from anesthesia:

(a) Provide reassurance.

(b) Speak in strong voice.

(c) Orient to place.

(d) Set limits on unacceptable behavior (e.g., inappropriate language).

b. Equipment

(1) Generally same as adult

2. PACU phase II

a. Anxiety of patient and family/responsible adult

(1) Maintain calm, reassuring manner.

(2) Provide privacy.

(3) Encourage expression of feelings.

(4) Give encouragement and positive feedback.

(5) Encourage parental/responsible adult presence if agreed by patient.

b. Assess patient for readiness for discharge to home, extended observation, or to extended care environment per facility policy/protocol.

c. Use discharge criteria as established by facility policy/protocol.

(1) Comply with standards set by American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses, state, and regulatory agencies.

3. Extended observation

a. Optimize privacy and comfort for extended stay.

(1) Assess environment for quieter, less busy area.

(2) Offer oral intake per ordered diet when appropriate.

(3) Assess need to use bathroom frequently.

(a) Offer assistance to bathroom as needed.

b. Provide options for interested adolescents for entertainment per availability (e.g., movies, hand-held electronic games, books or magazines, card games, music).

B. Postprocedural patient education

1. Extended observation/intervention

a. Include adolescent and accompanying adult(s) in patient education and discharge instructions as appropriate.

2. Ambulatory

a. Postprocedural instructions

(1) Provide written instructions to home care provider.

(2) Younger than 18 years

(a) Review instructions with the accompanying responsible adult(s), including the adolescent as much as possible in teaching.

(3) Eighteen years and older or emancipated/mature minors

(a) Review discharge instructions with the adolescent and assess understanding.

(b) Review instructions with the accompanying adult(s) to optimize postoperative care.

b. Follow-up visits as indicated (e.g., surgeon, physical therapy, postoperative teaching for equipment)

c. Provide information regarding procedure findings.

d. Provide instructions regarding home care.

(1) Activity

(a) Discuss impact of tests/procedures/surgery on daily living (e.g., expected return to work or school, driving, sports).

(2) Diet

(3) Medications

(a) Drug and food interactions

(4) Procedure-specific instructions

e. Enforce importance of compliance with postoperative instructions.

f. Confirm safe transport from facility with responsible adult.

g. Confirm that responsible adult will stay with patient upon return home.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses, 2008-2010 Standards of perianesthesia nursing practice. ( 2009)American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses, Cherry Hill, NJ.

2. In: (Editor: Chelley, J.E.) Peripheral nerve blocksed 2 ( 2004)Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

3. In: (Editors: DeFazio Quinn, D.M.; Schick, L.) Perianesthesia nursing core curriculum: Preoperative, phase I and phase II PACU nursing ( 2004)Saunders, St Louis.

4. Dreger, V.A.; Tremback, T.F., Management of preoperative anxiety in children, AORN J 84 (5) ( 2006) 778–790; quiz 805-808.

5. Hazinski, M.F., Manual of pediatric critical care. ( 1999)Mosby, St Louis.

6. Hicks, R.; Wenzer, L.J.; Reilly, C.A.; et al., Drug information handbook for perioperative nursing. ( 2006)LexiComp, Hudson, OH.

7. In: (Editors: Hockenberry, M.J.; Wilson, D.) Wong’s nursing care of infants and childrened 8 ( 2007)Mosby, St Louis.

8. Ireland, D., Unique concerns of the pediatric surgical patient: Pre-, intra-, and postoperatively, Nurs Clin North Am 41 (2006) 265–298.

9. James, S.R.; Ashwill, J.W.; Droske, S.C., Nursing care of children: Principles and practice. ed 2 ( 2002)Saunders, Philadelphia.

10. Justus, R.; Wyles, D.; Wilson, J.; et al., Preparing children and families for surgery: Mount Sinai’s multidisciplinary perspective, Pediatr Nurs 32 (1) ( 2006) 35–43.

11. LaMontagne, L.; Hepworth, J.T.; Salisbury, M.H.; et al., Effects of coping instruction in reducing young adolescents’ pain after major spinal surgery, Orthop Nurs 22 (6) ( 2003) 398–403.

12. In: (Editors: Lewandowski, L.A.; Tesler, M.D.) Family-centered care: Putting it into action: The SPN/ANA guide to family-centered care ( 2003)American Nurses Association, Washington, DC.

13. Marenzi, B., Body piercing: a patient safety issue, J Perianesth Nurs 19 (1) ( 2004) 4–10.

14. Neacsu, A., Malignant hyperthermia, Nurs Stand 20 (28) ( 2006) 51–57.

15. Romino, S.L.; Keatley, V.M.; Secrest, J.; et al., Parental presence during anesthesia induction in children, AORN J 81 (4) ( 2005) 780–792; quiz 793-796.

16. Smith, J.L.; Meldrum, D.J.; Brennan, L.J., Childhood obesity: a challenge for the anaesthetist?Paediatr Anaesth 12 (9) ( 2002) 750–761.

17. Tutag Lehr, V.; BeVier, P., Patient-controlled analgesia for the pediatric patient, Orthop Nurs 22 (4) ( 2003) 298–304; quiz 305-306.